Tropical West Southern Africa

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 31 total

Southern Africa (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Coasts, Grasslands, and Wetland Arcs at the Ice Age’s Edge

Geographic and Environmental Context

In the late Pleistocene, Southern Africa formed a twin world divided by latitude and rainfall, yet united by mobility and exchange.

To the south stretched Temperate Southern Africa — the Cape littoral, Drakensberg massif, Highveld grasslands, Karoo basins, and Namaqualand semi-deserts.

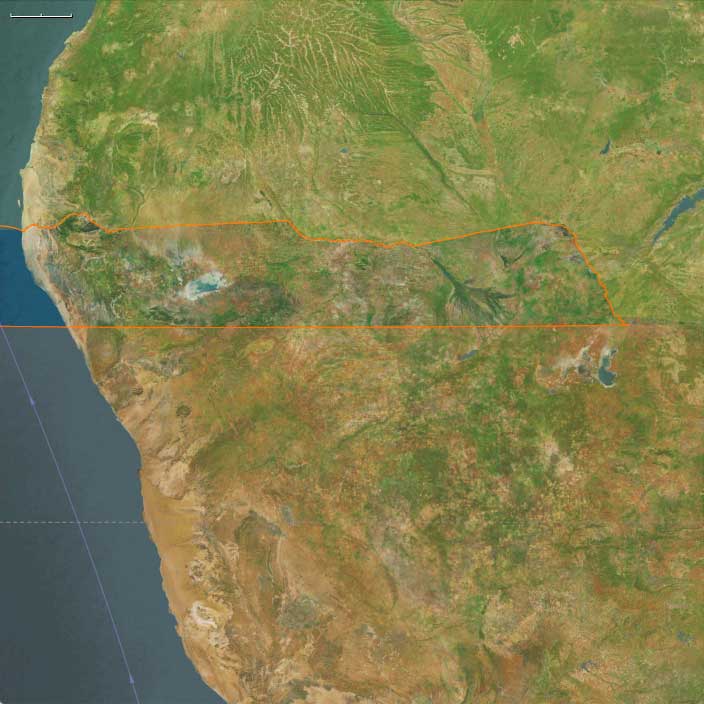

To the north lay Tropical West Southern Africa, encompassing the Okavango Delta, Etosha Pan, Caprivi wetlands, and the fog-fed Skeleton Coast of Namibia.

-

Along the Cape coast, sea levels stood nearly 100 m lower, exposing vast continental shelves and rich strand-plain hunting grounds.

-

Inland, grasslands extended across the Highveld and Limpopo basins, while the Drakensberg and Lesotho highlands were chilled by frost and occasional glacial patches.

-

Northward, the Okavango–Caprivi–Etosha system acted as an alternating chain of seasonal refugia amid the broader aridity of the Last Glacial Maximum.

-

The Namib fog belt, running down to the Skeleton Coast, linked desert and sea in a unique microclimate corridor.

Southern Africa thus was not a single environment but a pair of ecological theaters — a temperate coast–upland mosaic in the south and a wetland–desert archipelago in the north.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The epoch coincided with intensifying glacial cold across the globe.

Yet within this Ice-Age frame, Southern Africa remained a refuge — drier and cooler than today but never locked in ice.

-

In the temperate south, reduced rainfall contracted woodlands and expanded fynbos, karoo scrub, and open grasslands; winter storms strengthened along the Atlantic margin.

-

In the tropical north, summer monsoon belts retreated, leaving intermittent floods in the Okavango and Etosha basins and stabilizing the persistent fog regime on the coast.

-

Glacial cooling produced strong altitudinal zonation: frost-line vegetation in the Drakensberg, thornveld and savanna below, and semi-desert farther west.

Seasonal contrasts were sharper, but the diversity of habitats offered resilience few Ice-Age regions could match.

Lifeways and Settlement Patterns

Foragers across Southern Africa built dual economies that revolved around mobility between stable refugia and opportunistic resource zones.

-

Temperate foragers (the ancestors of the strandlopers) lived between coast and grassland, harvesting shellfish, fish, and seabirds along the exposed Cape plains, while inland groups hunted zebra, wildebeest, and springbok on the Highveld and Karoo.

Rock shelters in the Cederberg and Drakensberg served as cold-season refuges and social nodes. -

Tropical West Southern foragers organized life around water: fishing, trapping, and gathering in the Okavango floodplains during high water, then shifting to pan edges and spring corridors as the delta receded.

Others ranged along the Skeleton Coast for strandings, shellfish, and eggs, returning inland before the fog belt dried out.

This north–south complementarity gave the region a latitudinal rhythm of survival: coastal–grassland circuits in the south mirrored wetland–pan circuits in the north, both sustained by deep ecological mapping.

Technology and Material Culture

Both worlds drew from the Late Middle Stone Age technological repertoire but tuned it to their environments.

-

Stone industries: flake and blade cores of quartz, chert, or calcrete, with backed pieces and retouched scrapers emerging late.

-

Organic tools: bone points, hide awls, digging sticks weighted by stone rings, and fiber nets.

-

Symbolic and practical innovation: ostrich-eggshell beads for adornment and, more crucially, OES flasks for water storage — a hallmark of Southern African ingenuity.

-

Ochre was ubiquitous in both ritual and hide treatment, anchoring a long symbolic tradition.

While distinct in raw material, these toolkits spoke a common technological language of light, portable adaptability.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Southern Africa’s inhabitants were consummate travelers, moving through a lattice of ecological corridors rather than fixed territories.

-

In the south, the Cape–Karoo–Namaqualand coastline functioned as a continuous forager highway linking shellfish coves and inland grassland basins.

The Drakensberg passes opened seasonal routes between coastal plains and upland hunts. -

In the north, floodplain ridges and island chains of the Okavango guided east–west movement; Omiramba fossil rivers connected wetlands to Etosha; and Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando levees provided trans-basin crossings.

Even the foggy Skeleton Coast formed a linear migration route, its beaches serving as landmarks and occasional larders.

Through such corridors, material styles and ritual customs circulated widely, linking populations across what would later be defined as desert and delta.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

Symbolic life flourished amid this ecological variety.

In the south, ochre-stained burials, bead caches, and early rock art motifs in Cederberg shelters hint at ritual storytelling and ancestral marking of place.

In the north, pigment caches, hearth renewal rituals at pan-edge camps, and the exchange of bead strings performed similar social functions.

Across both zones, color, fire, and pattern embodied continuity: every hearth and painted stone a reaffirmation of belonging in landscapes that never stood still.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Resilience in Southern Africa came from diversification and knowledge rather than abundance.

Foragers mastered micro-climates, timing their movements with rainfall, flood pulses, and marine upwelling cycles.

Technologies such as ostrich-eggshell water storage, tailored hides, and lightweight shelters allowed year-round mobility.

Social networks stretched across biomes, ensuring mutual support during drought or cold snaps.

In contrast to the glaciated north, Southern Africa remained a living subcontinent — its people agents, not refugees, of the Ice Age.

Transition Toward the Last Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, both subregions were firmly established as enduring refugia:

-

Temperate Southern Africa maintained rich coastal and grassland economies, its rock-shelter traditions deepening into the symbolic complexity that would define the Later Stone Age.

-

Tropical West Southern Africa sustained flexible wetland–desert lifeways, its networks of floodplain, pan, and fog-shore camps forming one of the most intricate adaptive mosaics on Earth.

Together they formed a southern hinge of resilience — a world of foragers who thrived, not merely endured, beneath glacial skies.

Southern Africa’s dual systems of coast and delta would endure into the Holocene, exemplifying the Twelve Worlds principle: that human stability arises from ecological plurality, not uniformity.

Tropical West Southern Africa (49,293 – 28,578 BCE) Upper Pleistocene I — Wetland Lifelines, Pan Edges, and Desert-Fog Shores

Geographic and Environmental Context:

Tropical West Southern Africa includes the far-northern zones of Botswana and Namibia, including the Okavango Delta, the Zambezi–Chobe–Caprivi Strip wetlands, the Etosha Pan basin and surrounding thornveld, and the Namib’s Skeleton Coast fringe.

Anchors: Okavango Delta (Boro–Thamalakane–Khwai distributaries), Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando/ Kwando–Linyanti–Caprivi channels and floodplains, Etosha Pan (Oshigambo–Oshivelo margins, Ekuma–Omuramba inlets), Owambo/ Cuvelai seasonal rivers, and the Skeleton Coast (surf-battered gravel plains, fog-fed lichen fields, seal rookeries).

-

Okavango received attenuated headwaters from the Angolan highlands, spreading into seasonal marshes and islands;

-

Etosha Pan alternated between shallow saline lake and wind-bared playa, with woodland belts on its margins;

-

Caprivi housed distributary floodplains and gallery forests along Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando;

-

Skeleton Coast offered fog-fed strandlines rich in beached carrion and seabird rookeries.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Last Glacial Maximum (LGM): cooler, drier interior; rain belts contracted north; Okavango floods smaller and more variable; Etosha more frequently dry; persistent coastal fogs on the Skeleton Coast.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Forager bands shuttled between wetland refugia (Okavango/Caprivi channels) and pan edges (Etosha margin springs), hunting antelope and small game, gathering bulbs, fruits, and nuts;

-

Coastal foragers exploited strandings (whale, seal), shellfish pockets, and beach birds along the Skeleton Coast, with brief seasonal stays.

-

Camps clustered near perennial springs, island thickets, and pan-edge seeps.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Flake/core stone industries (quartz, chert, calcrete); backed pieces emerge late; bone points; digging sticks weighted with stone rings; ostrich eggshell (OES) water flasks and beads.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Floodplain ridges and palm-island chains guided movements through the Okavango;

-

Omiramba (fossil river) corridors led into Etosha margins;

-

Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando levees enabled seasonal traversal;

-

Fog-shorelines served as linear routes along the Skeleton Coast.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

OES bead kits; pigment use (red/ yellow ochres) at island and pan-edge shelters; ritual hearth renewal at spring camps.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Wetland–pan–coast switching hedged risks; eggshell flasks and knowledge of spring timing critical for LGM survival.

Transition

By 28,578 BCE, foragers had mapped a tri-zonal safety net — Okavango, Etosha margins, Caprivi channels — with episodic forays to the Skeleton Coast.

Tropical West Southern Africa (28,577 – 7,822 BCE) Upper Pleistocene II — Deglaciation, Larger Floods, and Pan-Woodland Mosaics

Geographic and Environmental Context:

Tropical West Southern Africa includes the far-northern zones of Botswana and Namibia, including the Okavango Delta, the Zambezi–Chobe–Caprivi Strip wetlands, the Etosha Pan basin and surrounding thornveld, and the Namib’s Skeleton Coast fringe.

Anchors: Okavango Delta (Boro–Thamalakane–Khwai distributaries), Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando/ Kwando–Linyanti–Caprivi channels and floodplains, Etosha Pan (Oshigambo–Oshivelo margins, Ekuma–Omuramba inlets), Owambo/ Cuvelai seasonal rivers, and the Skeleton Coast (surf-battered gravel plains, fog-fed lichen fields, seal rookeries).

-

Rising rainfall during interstadials enlarged Okavango inundations and Caprivi wetlands; woodland belts thickened around Etosha and the Owambo/ Cuvelai drains.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød: increased summer rains boosted channel floods, island growth, and riparian mast;

-

Younger Dryas: drought pulse contracted marsh edges;

-

Early Holocene: warming and stronger ITCZ rains stabilized flood regimes.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Semi-recurrent floodplain camps exploited fish runs (catfish/ tilapia), flood-recession grazing antelope, and riparian fruits;

-

Etosha margin hunts targeted springbok, zebra, oryx near permanent water;

-

Caprivi supported large wet-season encampments on levees;

-

Skeleton Coast remained a short-visit zone for carrion/ shellfish.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Microlithic bladelets & backed segments; bone harpoons/ gorges; woven fish-baskets; OES water flasks & beads; grindstones for geophytes/ seeds.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Seasonal Okavango distributaries (Thamalakane–Boro–Khwai) and Caprivi levee paths let groups circulate with flood pulse timing;

-

Etosha access via Omuramba saddles.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Bead strings and pigment caches deposited at long-lived island groves and pan-edge shelters; first engravings on calcrete/ dolomite slabs near Etosha implied.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Pulse-following mobility and broad-spectrum diets blunted drought stress of the Younger Dryas.

Transition

By 7,822 BCE, people were tuning lifeways to flood pulses — a forager hallmark of this aquatic-savanna frontier.

Southern Africa (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Rising Seas, Flood Pulses, and Shell-Midden Shores

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the long swing from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Early Holocene, Southern Africa cohered as a single water-anchored world.

Two complementary spheres organized lifeways:

-

Temperate Southern Africa — the Cape littoral and fynbos, Namaqualand, Highveld grasslands, Drakensberg–Lesotho massif, Karoo, and the Maputo–Limpopo basins—where rising seas carved modern embayments and lagoons and river valleys remained fertile through climatic swings.

-

Tropical West Southern Africa — the Okavango Delta, Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando/Linyanti–Caprivi wetlands, the Etosha Pan system and Owambo/Cuvelai drains, and the fog-nourished Skeleton Coast—an aquatic–savanna frontier driven by flood pulses and ITCZ rains.

Together these belts formed a ridge–river–coast continuum: shell-rich coves and estuaries at the Cape, grassland and spring corridors inland, and pulsing floodplains and pans to the north.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE): Warmer, wetter conditions greened fynbos and Highveld grasslands; Okavango inundations broadened and Caprivi wetlands expanded; woodland belts thickened around Etosha and along the Owambo/Cuvelai drains.

-

Younger Dryas (c. 12,900–11,700 BCE): A brief cool–dry pulse contracted marsh edges and inland water bodies; coastal reliance intensified along the Cape and Namaqualand; floodplain use narrowed to perennial channels and levees.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): Climatic stabilization brought stronger summer rains in the north and reliable winter–spring moisture in the south; flood regimes regularized, lagoons matured, and grasslands recovered.

Subsistence & Settlement

A continent-spanning broad-spectrum portfolio matured, balancing semi-sedentary anchoring with seasonal mobility:

-

Coasts (Temperate south): Strandloper adaptations flourished—large shell middens formed along the Cape and Namaqualand, with fish, mussels, limpets, seals, and seabirds as staples. Semi-sedentary cove camps persisted near rich shorelines and estuaries; inland rounds targeted antelope and dug geophytes in fynbos and grasslands.

-

Floodplains & pans (Tropical west): Semi-recurrent levee camps followed fish runs (catfish/tilapia), flood-recession grazing of antelope, and riparian fruits. The Caprivi supported large wet-season encampments on high levees; Etosha margin hunts focused on springbok, zebra, oryx near permanent water; the Skeleton Coast remained a short-visit zone for carrion and shellfish.

Across both spheres, settlement knit together resource-rich nodes—coves, levees, springs, and rock shelters—reoccupied across generations.

Technology & Material Culture

Toolkits were light, durable, and tuned to water:

-

Microlithic bladelets and backed segments for composite arrows and spears.

-

Fish gorges, bone harpoons, woven basket traps, and stake weirs for estuary and floodplain capture.

-

Grinding slabs for wild plant processing; basketry and cordage for transport and drying racks.

-

Ostrich eggshell (OES) flasks for water carriage and abundant OES beads as exchange media.

-

Early rafts/dugouts likely in calm estuaries and distributaries.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Mobility braided coasts, valleys, pans, and deltas into one exchange field:

-

Coastal corridors linked shell-midden coves with river mouths and inland passes to the Highveld and Drakensberg.

-

Flood-ridge “causeways” among Okavango palm islands, Caprivi levee paths, and Omuramba routes to Etosha organized pulse-following rounds.

-

The Maputo–Limpopo system and interior river valleys moved beads, pigments, dried fish, and hides between grassland and shore.

These routes created redundancy: when drought pinched a basin or a run failed, another habitat or partner camp stabilized supply.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Symbolic life was vivid and place-anchored:

-

Rock art in Drakensberg and Cederberg shelters flourished—polychrome animal–human scenes, trance dances, and eland-linked ceremonies.

-

Shell middens functioned as ancestral markers at coastal landings; bead strings and pigment caches accumulated at island groves and pan-edge shelters in the north.

-

Seasonal feasts at fish peaks and flood-begin events renewed access rules to weirs, springs, and groves—ritual governance of resources.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Security rested on storage + scheduling + multi-ecozone use:

-

Smoked/dried fish and meats, rendered fats, roasted seeds, and stored geophytes buffered lean months and Younger Dryas stress.

-

Seasonal anchoring at rich coasts and pulse-following mobility across wetlands and pans spread risk.

-

Edge-habitat focus (back-bar lagoons, riparian woods, pan margins) maximized predictable returns as conditions shifted.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Southern Africa had stabilized as a water-anchored forager world: shell-midden communities lined the temperate coasts, and floodplain societies tuned lifeways to the Okavango–Caprivi–Etosha pulse. The shared operating code—portfolio subsistence, storage, seasonal anchoring with mobile spokes, bead-mediated exchange, and shrine-marked tenure—set the durable foundation for later Holocene traditions of coastal strandlopers, floodplain specialists, and, eventually, pastoral and farming horizons on the distant skyline.

Tropical West Southern Africa (7,821 – 6,094 BCE) Early Holocene — Flood-Pulse Villages and Rift-to-Delta Circuits

Geographic and Environmental Context:

Tropical West Southern Africa includes the far-northern zones of Botswana and Namibia, including the Okavango Delta, the Zambezi–Chobe–Caprivi Strip wetlands, the Etosha Pan basin and surrounding thornveld, and the Namib’s Skeleton Coast fringe.

Anchors: Okavango Delta (Boro–Thamalakane–Khwai distributaries), Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando/ Kwando–Linyanti–Caprivi channels and floodplains, Etosha Pan (Oshigambo–Oshivelo margins, Ekuma–Omuramba inlets), Owambo/ Cuvelai seasonal rivers, and the Skeleton Coast (surf-battered gravel plains, fog-fed lichen fields, seal rookeries).

-

Okavango approached highstand hydrology with extensive papyrus/hippo channels; Caprivi distributaries broadened; Etosha alternated between shallow water and saline playa with wooded margins.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Holocene thermal optimum: stronger summer rainfall, predictable flood pulses; inland droughts mild and short.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Seasonal semi-sedentary hamlets on Okavango levees: fish weirs/ traps, floodplain antelope drives, waterfowl netting, reed rhizome/ water-lily harvest;

-

Etosha/ Owambo: persistent spring-edge camps; small-game/ antelope hunting, seed/ tuber collecting;

-

Caprivi: wet-season congregation on high levees, dry-season dispersion to pans/ springs.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Microlithic composites on reed/wood shafts; nets, basketry fish traps; grindstones; OES flasks and beads; early pottery at fringes unlikely yet.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Flood-ridge “causeways” among palm islands; Zambezi–Chobe canoe drifts; Omuramba paths around Etosha.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Structured hearths and bead caches at “home” levees; healing/ rain-making rites at pans and spring mounds; trance dance traditions deepen.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Storage (smoked fish, dried meat, roasted seeds) + island refugia sustained wet/dry seasonal security.

Transition

By 6,094 BCE, floodplain–pan communities had settlement memory — places ritually and practically central to subsistence.

Southern Africa (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Flood Pulses, Forested Shores, and a Golden Age of Image and Song

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Early Holocene, Southern Africa cohered as a single hydrological tapestry: the Cape littoral and fynbos, Highveld grasslands and the Drakensberg–Lesotho massif, the Karoo and Namaqualand margins, and—northward—the Okavango–Zambezi–Chobe–Caprivi floodplains, Etosha’s pan–spring system, and the fog-nourished Skeleton Coast.

Warmer, wetter conditions raised river stages and swelled wetlands; grasslands were lush; estuaries and rocky coves along the Cape brimmed with marine life. Across both Temperate Southern Africa and Tropical West Southern Africa, landscapes stabilized into reliable seasonal engines that anchored larger, longer-lived forager settlements than in the late Pleistocene.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal optimum brought stable, warm, moisture-rich regimes:

-

In the temperate south, dependable rainfall fed perennial streams, seeps, and valley wetlands; fynbos productivity surged.

-

In the tropical north, predictable flood pulses coursed through the Okavango and Caprivi distributaries; Etosha oscillated between shallow waters and saline playa fringed by thornveld.

-

Coastal upwelling and surf-exposed shores along the Cape ensured year-round shellfish and fish abundance.

This hydroclimatic equilibrium supported semi-sedentary anchoring at rivers, levees, pans, and coves, with seasonal forays that stitched biomes together.

Subsistence & Settlement

A continental portfolio subsistence matured, combining permanence with mobility:

-

Temperate belts (Cape–Highveld–Drakensberg–Karoo/Namaqualand): large seasonal villages formed on rivers and coastal terraces. Diets blended shellfish, intertidal fish, and waterfowl with nuts, geophytes, fruits, and antelope from grassland and fynbos ecotones.

-

Tropical floodplains and pans (Okavango–Caprivi–Etosha): levee hamlets worked fish weirs/traps, netted waterfowl, drove floodplain antelope, and harvested reed rhizomes and water-lilies; spring-edge camps around Etosha paired small-game hunts with seed and tuber gathering.

Across both spheres, households returned to the same “home” nodes (levees, springs, dune bars, caves), building place memory and routinized storage.

Technology & Material Culture

Toolkits were light, durable, and water-savvy:

-

Microlithic composite arrows with widespread bows; grinding slabs, bone awls, and sinew thread for leather and net repair.

-

Nets, basketry fish traps, and stake weirs in floodplains and estuaries; dugout or raftlike craft in calm reaches.

-

Ostrich eggshell (OES) flasks for water transport and abundant OES beads as exchange tokens.

-

Pottery remains unlikely this early in these zones, but organic containers and smoke-drying racks left a strong storage signature.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Mobility braided uplands, lowlands, and coasts into one exchange field:

-

The Drakensberg–Highveld–Limpopo axis funneled hides, pigments, shell ornaments, and dried foods between mountains, plateau, and river basins.

-

In the north, flood-ridge “causeways” among palm islands, Zambezi–Chobe canoe drifts, and Omuramba paths around Etosha linked seasonal camps.

-

Cape coastal strips connected shell-rich coves with inland valleys; bead trails—especially OES bead chains—traced kin and ritual ties over long distances.

These routes produced redundancy: when a run failed or a pan dried, another habitat or partner settlement filled the gap.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

The period witnessed a rock-art fluorescence unparalleled in its symbolic density:

-

In the Drakensberg and Cape ranges, finely shaded polychromes depicted animal–human spiritual scenes, trance dances, and eland-centered ceremonies, encoding rainmaking, healing, and transformation.

-

On northern pans and springs, bead caches, structured hearths, and healing/rain rites anchored settlement memory; trance traditions deepened with flood-pulse rhythms.

-

Along the coasts, shell-midden feasts functioned as ancestral monuments, renewing access rights to fisheries and foraging grounds.

Ritual did more than reflect subsistence—it governed access, timed movement, and knit far-flung camps into moral communities.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Households engineered security through storage, scheduling, and multi-ecotone use:

-

Smoke-dried fish, dried meats, roasted seeds and nuts, and rendered fats sustained overwintering and dry-season gaps.

-

Seasonal rounds (coast/river ↔ upland/pan) buffered climate noise; island refugia in the Okavango and spring mounds at Etosha offered drought insurance.

-

Tenure customs, marked by shrines, art, and feasting places, regulated pressure on key stocks (weirs, shell banks, berry groves), limiting conflict and overtake.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Southern Africa had crystallized into a symbolically rich, storage-capable forager world: large seasonal villages on rivers and coasts in the south; flood-pulse hamlets and spring-edge camps in the north—each tied by exchange corridors and a shared ritual grammar.

These lifeways—portfolio subsistence, water-anchored settlement, bead-mediated alliances, and shrine-marked tenure—formed the durable substrate on which later herding frontiers (visible on distant horizons) and farmer networks would graft, without erasing the region’s deep art of place.

Southern Africa (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Abundance, Ceremony, and the Mapping of Sacred Land

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Middle Holocene, Southern Africa—spanning the Cape littoral, Highveld grasslands, Drakensberg massif, Kalahari margins, and the great wetlands of the Okavango and Caprivi—entered a period of remarkable climatic stability and cultural flourishing.

The Hypsithermal warm phase brought moderate temperatures, sustained rainfall, and flourishing vegetation across both the temperate south and tropical northern belt, transforming the subcontinent into one of the most biologically and ecologically diverse regions on Earth.

Two complementary cultural worlds matured in balance:

-

Temperate Southern Africa, encompassing the Cape, Highveld, Karoo, and Drakensberg, where fertile coasts and green uplands sustained rich foraging economies and complex spiritual traditions.

-

Tropical West Southern Africa, covering the Okavango–Zambezi floodplains, Etosha Pan, and Skeleton Coast, where mobile floodplain foragers built resilient exchange networks tied to wetlands and seasonal flows.

Together they formed a dynamic landscape of interconnected ecologies and shared symbolic geographies, linking coast, mountain, desert, and delta through trade, migration, and ritual.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal optimum provided one of the most favorable climatic windows in Southern African prehistory.

-

Rainfall was ample and consistent, maintaining perennial rivers and grasslands across the Highveld and Drakensberg foothills.

-

The Cape littoral enjoyed Mediterranean-like stability with predictable winter rains; fynbos vegetation thrived alongside shellfish-rich coasts.

-

Farther north, the Okavango Delta and Zambezi–Chobe–Caprivi floodplains pulsed seasonally with life, though interrupted by occasional multi-year dry spells.

-

Etosha Pan and the Namib coast oscillated between arid episodes and fog-fed fertility, creating contrasting yet complementary resource zones.

This climatic equilibrium enabled population expansion, regional mobility, and the emergence of ceremonial landscapes linking ecological diversity with spiritual continuity.

Subsistence & Settlement

Subsistence in Southern Africa was characterized by ecological precision and adaptive diversity:

-

Temperate regions supported coastal strandloper communities, who harvested shellfish, fish, and seals along the Atlantic and Indian Ocean shores, supplementing with root crops, nuts, and game from inland valleys. Inland, Highveld and Karoo hunters followed herds of antelope and zebra, while upland Drakensberg foragersrotated between grassland and cave shelters.

-

Tropical wetlands of the north sustained complex forager–fishers who harvested water-lilies, catfish, bream, and wildfowl during flood peaks, shifting to nuts, bulbs, and small game as waters receded.

-

Etosha and Caprivi groups established semi-permanent bases on floodplain levees, redistributing fish, meat, and beads through kinship exchange.

-

Across all regions, multi-habitat scheduling—coast, river, highland, and pan—ensured year-round food security and minimized ecological risk.

Settlement was semi-permanent but cyclic, anchored to enduring landmarks such as caves, springs, and rock shelters—places that accumulated generations of ritual memory.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological traditions maintained their microlithic precision and versatility:

-

Stone and bone toolkits were finely adapted for hunting, woodcutting, and fishing.

-

Nets, traps, and fish baskets proliferated in the north; poisoned arrows (notably beetle toxins) became a standard weapon.

-

Along the coast, dugout canoes and rafts facilitated shellfish collection and lagoon fishing.

-

Ostrich eggshell (OES) beads, exchanged over hundreds of kilometers, served as social tokens linking floodplain and inland communities.

-

In the south, the absence of pottery was offset by skillful use of organic containers, leather pouches, and woven baskets.

These technologies, light and portable, reflected societies grounded in mobility, trade, and environmental attunement rather than accumulation.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Southern Africa was crisscrossed by seasonal and ceremonial pathways that linked distant ecologies:

-

The coastal corridors of the Cape connected shellfish gatherers and inland bead-makers, moving marine resources deep into the interior.

-

Highveld–Drakensberg routes carried pigment stones, hides, and ritual objects among cave-sanctuary networks.

-

In the north, the Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando and Okavango–Etosha systems formed arterial trade channels uniting wetland, woodland, and desert groups.

-

Bead trails and kinship alliances bridged linguistic and ecological zones, turning exchange into both material and symbolic diplomacy.

These corridors created a pan-southern web of interaction, through which goods, songs, and stories traversed landscapes as fluidly as the rivers and herds they followed.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

The Middle Holocene saw the intensification of ritual and visual expression:

-

Rock art flourished across the Drakensberg, Cederberg, and Brandberg ranges, depicting humans and animals intertwined in scenes of transformation and trance.

-

In the temperate south, herding motifs appeared long before the actual introduction of livestock—likely symbolic visions of spiritual herds encountered in trance, signifying foresight rather than fact.

-

Rainmaking ceremonies centered in mountain caves and river confluences; paintings often depicted eland, the archetypal rain animal.

-

In the north, engraved boulders and geometric petroglyphs at pan margins and floodplains encoded ancestral narratives of water, fertility, and kinship.

-

Trance rituals and communal feasts synchronized seasonal movement, reinforcing unity among dispersed groups.

Through these symbolic practices, the landscape itself became a sacred archive, every rock face and spring imbued with meaning.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience stemmed from cultural flexibility and ritual reinforcement:

-

Diversified subsistence—combining wetland, coastal, and upland resources—reduced ecological vulnerability.

-

Mobility and alliance networks redistributed food and goods during drought cycles.

-

Ritualized knowledge systems, including rainmaking and divination, acted as adaptive social tools for forecasting and decision-making.

-

The balance of ritual and resource use ensured long-term ecological stability—each harvest, hunt, or gathering framed as reciprocal exchange with the spirit world.

This was an era when ritual and subsistence were one, making spiritual practice itself a strategy of environmental management.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Southern Africa had evolved into a continent of ritual landscapes and ecological mastery.

Foragers across the Cape, Kalahari, and Okavango had not yet adopted herding, but their social, symbolic, and logistical systems were already advanced, sustaining widespread networks and deep cultural cohesion.

The spiritual anticipation of livestock in rock art prefigured the pastoral frontier soon to arrive from the north; meanwhile, the wetland–highland–coast continuum of exchange provided the enduring framework for later interaction between foragers, herders, and farmers.

The Middle Holocene in Southern Africa thus represents a golden equilibrium—a time of abundance managed through ritual, art, and alliance, when people and landscape lived in mutual recognition and rhythm.

Tropical West Southern Africa (6,093 – 4,366 BCE) Middle Holocene — Dry Pulses, Forager Mastery, and Long-Distance Links

Geographic and Environmental Context:

Tropical West Southern Africa includes the far-northern zones of Botswana and Namibia, including the Okavango Delta, the Zambezi–Chobe–Caprivi Strip wetlands, the Etosha Pan basin and surrounding thornveld, and the Namib’s Skeleton Coast fringe.

Anchors: Okavango Delta (Boro–Thamalakane–Khwai distributaries), Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando/ Kwando–Linyanti–Caprivi channels and floodplains, Etosha Pan (Oshigambo–Oshivelo margins, Ekuma–Omuramba inlets), Owambo/ Cuvelai seasonal rivers, and the Skeleton Coast (surf-battered gravel plains, fog-fed lichen fields, seal rookeries).

-

Interior dry pulses shortened flood durations; Okavango still reliable; Etosha often dry but spring-fed; Caprivi wetlands remained a backbone.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Warm/ wet baseline, punctuated by several multi-year dry phases; fogs persist along Skeleton Coast.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Foragers tightened scheduling: front-load fish/ water-lily harvest in peak floods; shift to nuts/ bulbs/ small game when waters withdrew;

-

Etosha: spring-edge scheduling critical;

-

Caprivi: high-levee bases used as redistribution nodes.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Microlithic kit remained; fish baskets refined; poison arrows (beetle toxins) normalized; OES beads in large quantities—regional exchange tokens.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando linked westward into Angola, eastward toward upper Zambezi; bead trails trace inter-group exchange.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Engraved boulders and pecked geometric panels at pan edges; trance motifs proliferated; kinship feasts structured alliances.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Portfolio livelihood + mobile alliances spread climate risk across floodplain networks.

Transition

By 4,366 BCE, Tropical West Southern Africa’s foragers had a mature exchange society keyed to flood dynamics.

Tropical West Southern Africa (4,365 – 2,638 BCE) Late Neolithic/Chalcolithic — First Livestock at the Margins and Wetland–Pasture Pairing

Geographic and Environmental Context:

Tropical West Southern Africa includes the far-northern zones of Botswana and Namibia, including the Okavango Delta, the Zambezi–Chobe–Caprivi Strip wetlands, the Etosha Pan basin and surrounding thornveld, and the Namib’s Skeleton Coast fringe.

Anchors: Okavango Delta (Boro–Thamalakane–Khwai distributaries), Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando/ Kwando–Linyanti–Caprivi channels and floodplains, Etosha Pan (Oshigambo–Oshivelo margins, Ekuma–Omuramba inlets), Owambo/ Cuvelai seasonal rivers, and the Skeleton Coast (surf-battered gravel plains, fog-fed lichen fields, seal rookeries).

-

Pastoral streams from the north/ northwest reached the Caprivi fringe; Okavango floodplain edges offered seasonal grazing; Etosha margins served as dry-season pasture.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Slight drying trend; flood pulses remained annual but sometimes reduced.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Sheep/goat appear in small numbers among forager camps near Caprivi–Okavango by late in this window;

-

Herding remained supplemental to fishing/ gathering/ hunting.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Pottery begins to appear in small quantities (cooking/ storage); continued microlithic hunting kit; leather water bags complement OES flasks.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Pastoral–forager exchange corridors along Zambezi–Chobe and Okavango levees; hides, meat, fish traded for stock access/ milk.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Rock art starts to display domestic animal forms near flood edges; ritual proscriptions govern water access and grazing.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Wetland–pasture complementarity spreads risk; milk/ meat add protein buffers to flood-season storage.

Transition

By 2,638 BCE, mixed forager–pastoral mosaics had formed along the Okavango–Caprivi–Etosha belt.

Southern Africa (4,365 – 2,638 BCE): Late Neolithic / Chalcolithic — Coasts of Plenty, Highveld Gardens, and the First Herds

Geographic & Environmental Context

Southern Africa in this epoch formed a continuous land–water mosaic: fynbos and rich upwelling coasts along the Cape and Namaqualand, broad Highveld grasslands and Drakensberg–Lesotho headwaters, the Great Karoo’s basins, and, to the north, wetland belts—Okavango, Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando/Linyanti–Caprivi, and the Etosha pans—grading into thornveld and Skeleton Coast fog shores. These belts linked marine protein, riverine floodplains, and interior pastures into one integrated resource field.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Conditions were generally stable but drier pulses pressed the Karoo and Namaqualand. The Highveld held reliable rainfall; northern wetlands kept annual flood pulses, though some years ran lower. Coastal upwelling remained productive; inland, moisture gradients sharpened the contrast between wetland margins and open savannas, steering seasonal movement.

Subsistence & Settlement

Forager communities sustained diverse coastal and inland economies: shellfish, line-fish, and strand-lop harvests on the Cape; antelope, small game, and plant foods across grassland and scrub.

Late in the window (c. mid–late 3rd millennium BCE), first livestock—sheep/goats—entered from the west coastal corridor, appearing in small numbers in the Cape–Namaqualand and at the Okavango–Caprivi–Etoshamargins. Herding was initially supplemental, folded into long-standing seasonal rounds rather than replacing them. Fishing, floodplain foraging, and small-game hunting continued as staples.

Technology & Material Culture

Microlithic hunting kits and stone adzes remained core. Pottery diffused gradually from the north, first as small cooking and storage vessels in wetland and corridor camps, complementing ostrich eggshell (OES) flasks and leather water bags. Early pastoral kraal forms appeared at favored springs and lee-slopes. Along the coast, robust shell-working and bone points persisted; in wetlands, basketry and fish traps accompanied flood-season harvests.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Two braided systems organized movement:

-

The west-coast Namib–Namaqualand corridor, carrying stock and herding know-how toward the Cape littoral and inland basins.

-

The wetland–levee corridors of Zambezi–Chobe–Okavango–Caprivi–Etosha, where forager–pastoral exchanges brokered milk access, grazing rights, hides, and fish.

Transmontane tracks tied Drakensberg watersheds to the Limpopo–Maputo basins, moving stone, pigments, shells, and foodstuffs across elevation belts.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Rock art began to depict sheep and goats even before they were widely herded, signaling prestige, novelty, or ritual potency. Long-standing emphases on rainmaking and fertility endured; coastal and floodplain feasts left dense midden signatures. Emerging kraals and favored waterholes gained ancestor and place-guard associations, and grazing/water taboos helped regulate access at sensitive moments in the flood–drought cycle.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience rested on mobility plus diversification. Coastal fisheries and shellfish beds buffered lean inland years; wetland–pasture pairing spread risk across seasons; small herds added milk and occasional meat as protein insurance during dry pulses. Kraal siting, rotational grazing, and continued forager breadth limited local overuse. Storage strategies—drying, smoking, and cached shellfish—smoothed shortfalls, while intergroup exchange redistributed surpluses after poor runs or failed rains.

Long-Term Significance

By 2,638 BCE, Southern Africa had become a mixed forager–pastoral landscape in embryo: maritime plenty at the Cape, durable river–pan livelihoods to the north, and the first livestock threading into established mobility systems. The region’s enduring pattern—portfolio subsistence, seasonal movement, and ritual regulation of water and pasture—set the ecological logic that later herding expansions, trade corridors, and highland–lowland exchanges would build upon in the Early Bronze–Iron Age horizons.