Andamanasia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 56 total

The Indian Ocean World, one of the twelve divisions of the Earth, is centered on the Indian Ocean and encompasses Madagascar, several small island groups, Maritime East Africa, Southeastern Arabia, Southern India, Sri Lanka, and Aceh—the northernmost tip of Sumatra. Its southernmost point is Kerguelen Island.

To the north of Madagascar, the island nations of the Comoros and the Seychelles are situated in the western Indian Ocean, while Mauritius lies to the east of the great island.

On the African mainland, the region includes portions of Mozambique, Malawi, Tanzania, Kenya, and Somalia, all of which also have cultural and historical ties to Afroasia.

The Arabian nations of Yemen and Oman face the heart of the Indian Ocean World, with their division aligning with the traditional boundary separating North India from South India and Sri Lanka.

To the west of Southern India, the Maldives form a prominent island chain within this maritime world.

Along the northeastern boundary, only Aceh, the northwesternmost tip of Sumatra, belongs to the Indian Ocean World, distinguishing it from the rest of the Indonesian archipelago.

HistoryAtlas contains 1,059 entries for the Indian Ocean World from the Paleolithic period to 1899.

Narrow results by searching for a word or phrase or select from one or more of a dozen filters.

The Moderns are taller, more slender, and less muscular than the Neanderthals, with whom they share—perhaps uneasily—the Earth.

Though their brains are smaller in overall size, they are heavier in the forebrain, a difference that may allow for more abstract thought and the development of complex speech.

Yet, the inner world of the Neanderthals remains a mystery—no one knows the depths of their thoughts or how they truly expressed them.

Southeast Asia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Sundaland Continents, Island Worlds, and the Dawn of Rock Art

Geographic & Environmental Context

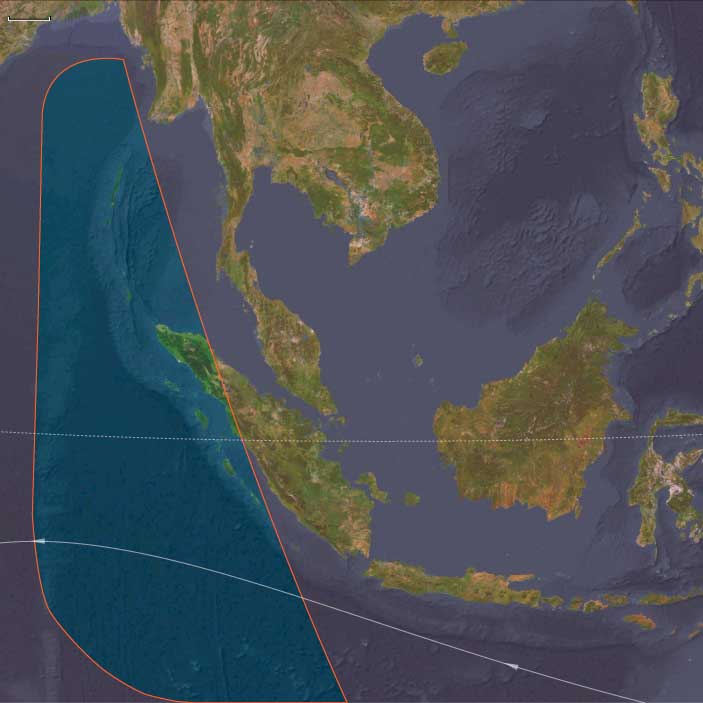

At the height of the Late Pleistocene glacial world, Southeast Asia presented two contrasting landscapes — the broad, continental plains of Sundaland and the fragmented islands of Wallacea and Andamanasia — together forming one of the planet’s richest and most diverse human realms.

-

Sundaland: With sea level 50–120 meters below present, the exposed shelf united Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and the Malay Peninsula into a single subcontinent threaded by enormous rivers (paleo-Mekong, Mahakam, Kapuas, Brantas, Musi). Its coastlines stretched hundreds of kilometers beyond today’s shores, forming wide savanna–forest mosaics, mangrove-fringed estuaries, and lagoons teeming with life.

-

Wallacea: Beyond the drowned shelf lay Sulawesi, the Moluccas, Banda, Halmahera, Timor, and the Philippines—a chain of volcanic and limestone islands divided by deep channels marking the Wallace Line. These crossings demanded deliberate navigation and early maritime technology.

-

Andamanasia: To the northwest, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, together with Aceh’s offshore arcs (Simeulue–Nias–Mentawai), Preparis–Coco, and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, formed isolated forested refugia edging the exposed Sunda shelf. Their reefs, mangroves, and turtle beaches stood largely unpeopled but ecologically robust.

This region, straddling the equatorial monsoon belt, offered every possible habitat: mountains, caves, mangroves, coral reefs, and inland plains—each a seasonal hub for late Pleistocene foragers.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Early Period (49–40 ka): Alternating warm–wet and cool–dry pulses governed by orbital forcing and monsoon strength. Forests waxed and waned, while lower sea levels extended savannas across exposed shelf flats.

-

Mid–Late Period (40–30 ka): Cooler, drier glacial trend; rivers incised deeper valleys, and interior lakes and wetlands shrank. On Sundaland, open woodlands and grasslands expanded, while the monsoon weakened and the dry season lengthened.

-

Approach to the LGM (after 30 ka): Intensified aridity inland; coastal productivity remained high as cold upwelling zones enriched fisheries. In Wallacea and Andamanasia, rainfall persisted in volcanic uplands and cloud-forest refuges, sustaining biodiversity through the glacial maximum.

These climatic oscillations required mobility and ecological flexibility, drawing humans toward coasts and river corridors where food remained predictable.

Human Societies and Lifeways

Sundaland Foragers

-

Population & Organization: Small, mobile bands of hunter–fishers numbering a few dozen individuals, moving seasonally between river valleys, forests, and estuaries.

-

Subsistence:

• Terrestrial: red deer, wild cattle (banteng), pigs, and forest birds; fruit, tubers, nuts, and honey.

• Aquatic: riverine fish, turtles, mollusks, and estuarine shellfish.

• Fire management maintained patchy mosaics that attracted game and improved travel routes. -

Settlements: Open camps along paleo-rivers and karstic caves (Lang Rongrien, Niah, Tabon) served as wet- and dry-season bases.

Wallacean Islanders

-

Maritime Expansion:

Short but deliberate crossings linked Bali–Lombok, Sulawesi, the Moluccas, and the Philippines. Voyagers likely used bamboo rafts or dugout craft, already capable of island-hopping across swift straits. -

Economy:

Coastal and reef exploitation dominated: fish, shellfish, turtles, and seabirds; inland forests provided sago palms, fruits, and nuts. -

Symbolism:

The world’s earliest known figurative rock art—hand stencils and painted animals in Sulawesi and Borneo (≥40,000 BP)—emerged here, marking one of humanity’s earliest symbolic revolutions.

Andamanasian Refugia

-

Status: Probably uninhabited or sparsely visited; nearby shelf coasts were rich in mangroves, turtles, and seabirds.

-

Role: Served as ecological storehouses—dense forests and reefs sustaining species that would repopulate coastlines when sea levels rose.

Technology & Material Culture

Across the region, technological diversity mirrored environmental range:

-

Stone industries: Large flakes, blades, and denticulates; hafted spear points and knives. Toolkits adapted to mixed forest and aquatic settings.

-

Organic tools: Bone and shell awls, barbed points, and fish gorges; woven nets and basketry inferred from indirect evidence.

-

Pigment and ornament: Red ochre for body painting and adhesive binders; perforated shell, tooth, and bone beads as markers of identity and alliance.

-

Fire technology: Controlled burning reshaped landscapes for hunting and plant gathering.

-

Maritime engineering: Simple rafts or canoes allowed crossing of deep channels—among the earliest seafaring experiments on Earth.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

River Arteries: The paleo-Mekong, Mahakam, and Kapuas systems functioned as “interior highways,” linking uplands to the exposed shelf coastlines.

-

Maritime Crossings:

• Wallace Line passages—Bali–Lombok, Makassar Strait, Molucca gaps—connected hunter–gatherer populations despite fierce currents.

• Philippine corridors—Luzon–Visayas–Mindanao and the Sulu arc—fostered early trade in shell, pigment, and worked bone.

• Andaman–Nicobar chains paralleled the Sunda coastline, possibly sighted but not yet permanently occupied.

These overlapping networks formed the world’s earliest complex seascape of interaction, prefiguring Holocene navigation traditions.

Belief and Symbolism

Southeast Asian peoples by this time had developed a sophisticated symbolic world:

-

Cave and rock art in Sulawesi, Borneo, and Palawan reveal enduring mythic narratives—animals, hand stencils, and spirit figures linked to hunting and fertility.

-

Ochre rituals and bead ornaments signified personal and group identity.

-

Animistic cosmologies likely centered on water, rock, and ancestral spirits inhabiting caves, springs, and trees—beliefs that would echo in later Austronesian spiritual systems.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Adaptation was rooted in mobility, flexibility, and knowledge sharing:

-

Ecological diversity—forests, coasts, savannas, and rivers—allowed resource substitution during climate downturns.

-

Fire and water mastery reshaped landscapes and improved predictability.

-

Distributed knowledge networks—oral mapping of water sources, seasonal winds, and fauna—anchored community resilience.

-

Littoral foraging provided a caloric safety net through the harshest glacial episodes.

These strategies ensured persistence through one of the most variable climatic regimes on Earth.

Long-Term Significance

By 28,578 BCE, Southeast Asia had achieved a remarkable cultural and ecological synthesis:

-

The Sundaland–Wallacea continuum fostered societies adept at both land-based and maritime living.

-

Rock art, ornamentation, and pigment use announced an enduring symbolic sophistication.

-

Island-hopping navigation and inter-band exchange forged the first Pacific seafaring tradition.

These foundations—broad-spectrum foraging, flexible mobility, and deeply symbolic worldviews—would underpin every later cultural transformation of the region, from Holocene coastal settlement to Neolithic agriculture and, millennia later, the great Austronesian voyaging dispersals that carried Southeast Asia’s legacy across the entire Pacific.

Andamanasia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE) Upper Pleistocene I — Ice-Age Shelves, Reef Flats, and Island Forest Refugia

Geographic and Environmental Context

Andamanasia encompasses:

-

Andaman Islands (North, Middle, South Andaman) and Nicobar Islands.

-

Aceh in northern Sumatra, with nearby islands (Simeulue, Nias, Batu, Mentawai).

-

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands.

-

The Preparis, Coco, and Little Coco Islands (off Myanmar).

Anchors: North–South Andaman coasts and reefs, Nicobar Great Channel, Aceh’s Weh Island and Lhokseumawe–Banda Aceh corridor, Simeulue–Nias–Mentawai arc, Preparis/Coco islets, Cocos (Keeling) lagoon.

-

Sea level ↓ ~100 m: Sunda Shelf largely exposed, connecting Sumatra to mainland SE Asia; Andamans/Nicobars remained island chains but closer to coastlines.

-

Islands: forested Andamans; Nicobars with mangrove–reef systems; offshore islands (Cocos, Preparis) exposed limestone flats.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Glacial maximum: cooler SSTs, stronger winter monsoon winds; rainfall suppressed, but coastal mangroves and refugia persisted.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Likely unpeopled yet, though possible transient visits from early coastal voyagers hugging Sunda margins.

-

Rich seabird/turtle rookeries, mangrove crabs, and reef fish provided high productivity if reached.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Not directly evidenced, but contemporaneous SE Asian foragers used flake/microblade toolkits; dugouts or bamboo rafts possible for coastal movement.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Sunda coastal highway skirted Nicobar–Andaman arc; exposed shelf meant short crossings from Sumatra → Nicobars → Andamans.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

None directly known; symbolic life inferred from mainland contexts (ochre, ornaments).

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

These islands acted as ecological storehouses awaiting human settlement.

Transition

By 28,578 BCE, Andamanasia’s forest–reef mosaics had matured as refugia; human settlement awaited deglaciation.

Southeast Asia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Deglaciation, Island Worlds, and the Age of Painted Caves

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, Southeast Asia transformed from a single vast continent—the Sunda Shelf—into the world’s largest archipelagic region.

As glaciers melted and sea level rose more than 100 m, the ancient plains that once joined Sumatra, Borneo, Java, and the Malay Peninsula vanished beneath the sea.

By 8,000 BCE, the modern configuration of islands, peninsulas, and straits had formed, creating the fragmented landscapes that define Southeast Asia today.

Two great cultural-ecological spheres emerged:

-

Southeastern Asia (mainland and Sundaic islands: Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Sulawesi, the Philippines, and surrounding seas) — a region of rock-shelter cultures, reef-foragers, and early voyagers.

-

Andamanasia (Andaman–Nicobar–Aceh–Mentawai arc) — a bridge corridor between the Bay of Bengal and the eastern Indian Ocean, where island foragers first adapted to rising seas through mobility and exchange.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The transition from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene thermal optimum reshaped every ecosystem:

-

Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500 – 19,000 BCE): cooler, drier conditions contracted tropical forests; open grasslands dominated the Sunda Shelf; coasts extended hundreds of kilometers seaward.

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700 – 12,900 BCE): abrupt warming and intensified monsoons regenerated rainforests, flooded valleys, and boosted reef productivity.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900 – 11,700 BCE): a brief return to cooler, drier climates reduced forest cover and lowered rainfall; many groups pivoted toward coastal and riverine foraging.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): renewed warmth and humidity stabilized monsoons, expanded mangroves, and created the modern deltaic and island environments of the region.

The sea’s advance transformed the old Sundaic plains into the Java, South China, and Andaman Seas, generating new migration corridors and refuges.

Subsistence & Settlement

Late Pleistocene–Holocene communities practiced broad-spectrum foraging, balancing marine and terrestrial resources as coasts shifted:

-

Mainland & Sundaic islands:

Cave and rock-shelter settlements proliferated—Niah (Borneo), Lang Rongrien (Thailand), Tabon (Palawan)—where people hunted deer, pigs, and macaques; gathered tubers, nuts, and fruit; and harvested shellfish, reef fish, and turtles.

As shorelines retreated inland, estuarine fisheries and mangrove gathering replaced the vast riverine plains of the glacial period. -

Andaman–Nicobar–Aceh–Mentawai arc:

Canoe-borne foragers settled the Andaman and Nicobar Islands early, maintaining mixed forest–littoral economies of wild yams, deer, pigs, fish, and turtle.

Nicobars and Mentawais saw itinerant villages around lagoons and palm belts, while Aceh’s capes supported estuarine hunters and reef gleaners.

The Cocos and Preparis islets remained largely uninhabited but intermittently visited.

Across the region, settlements cycled between coastal and upland zones, tracking resource pulses through seasonal mobility.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological versatility matched the diversity of habitats:

-

Blade–microlith industries adapted to hunting and woodworking.

-

Ground-stone adzes and shell tools appeared for tree felling and canoe shaping.

-

Bone harpoons and fish gorges expanded marine exploitation.

-

Nets, baskets, and bark containers aided storage and mobility.

-

Ornaments in shell, bone, and stone expressed group identity, while ochre marked both body and rock.

-

The period’s most enduring legacy lay in Sulawesi’s cave art, where hand stencils and depictions of babirusas and deer-pigs—painted more than 40,000 years ago and renewed in this epoch—attest to a continuous symbolic tradition of exceptional depth.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Rising seas did not isolate communities—they reorganized movement:

-

Philippines–Sulawesi–Moluccas–Banda arc: voyaging intensified along visible island chains; short open-sea hops of 50–100 km created one of the earliest sustained maritime networks on Earth.

-

Andaman–Nicobar–Aceh–Mentawai corridor: canoe routes linked rainforests and reefs, establishing exchange of shell, resin, and ochre long before later Austronesian expansion.

-

Mainland river valleys (Irrawaddy, Chao Phraya, Mekong, Red) remained arteries of movement, connecting highland hunters to emerging coastal fisheries.

In effect, Southeast Asia became a maritime crossroads, not a fragmented world.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Symbolic life flourished amid environmental flux:

-

Cave art and engraving traditions expanded across Sulawesi, Borneo, and mainland karsts.

-

Ritual burials with ochre, shell ornaments, and pig or turtle offerings emphasized ancestry and connection to place.

-

Portable ornaments—beads, pendants, animal carvings—spread widely, perhaps marking alliance networks.

-

In Andamanasia, shell-midden cemeteries and ritual fires expressed continuity across generations as shorelines advanced.

The human imagination here turned environmental change into cosmology, reflecting a worldview of islands as living entities linked by sea and spirit.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Adaptation relied on mobility, diversity, and exchange:

-

Coastal intensification—shellfish, reef fish, and turtle harvesting—buffered inland droughts during the Younger Dryas.

-

Forest knowledge systems diversified diets and materials; edible tubers, palms, and resinous trees provided fallback foods and technology.

-

Canoe voyaging maintained inter-island ties, reducing risk from local resource failure.

-

Populations tracked mangrove succession and coral growth, continuously resettling new lagoons as older coasts drowned.

The region’s peoples evolved a unique maritime–terrestrial dualism that would persist into later Holocene societies.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Southeast Asia had become a world of islands, caves, and canoes—a landscape defined by water, art, and mobility.

-

Southeastern Asia saw its great painted caves, the flourishing of maritime foraging, and the first truly island-based societies.

-

Andamanasia established continuous human occupation across its archipelagos, anticipating later Indian Ocean seafaring.

The epoch’s legacy was both environmental and cultural: a blueprint for the seagoing economies and symbolic richness that would, millennia later, carry Austronesian speakers and their descendants across the Indo-Pacific.

Andamanasia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE) Upper Pleistocene II — Deglaciation, First Foragers, and Littoral Colonization

Geographic and Environmental Context

Andamanasia encompasses:

-

Andaman Islands (North, Middle, South Andaman) and Nicobar Islands.

-

Aceh in northern Sumatra, with nearby islands (Simeulue, Nias, Batu, Mentawai).

-

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands.

-

The Preparis, Coco, and Little Coco Islands (off Myanmar).

Anchors: North–South Andaman coasts and reefs, Nicobar Great Channel, Aceh’s Weh Island and Lhokseumawe–Banda Aceh corridor, Simeulue–Nias–Mentawai arc, Preparis/Coco islets, Cocos (Keeling) lagoon.

-

Sea levels rose rapidly; Andamans/Nicobars isolated further from the mainland; Aceh’s capes eroded into modern form; Simeulue/Nias/Mentawai isolated as deep-sea islands.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød (warm/moist): expanded forest belts; rich fisheries.

-

Younger Dryas (cold/dry): contraction of vegetation; reliance on reef/turtle rookeries.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): forest expansion, stable lagoons.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Andaman Islands: earliest continuous settlement; microlith-using foragers hunted pigs, deer, and turtles; gathered tubers, yams, pandanus, wild fruit; shell middens accumulate.

-

Nicobars: canoe-borne foragers harvested coconuts, fish, turtle; shifting camps along lagoon passes.

-

Aceh & outer islands: seasonal foragers exploited coastal forests, estuaries, reefs.

-

Cocos/Preparis: likely uninhabited, but visited episodically.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Microliths, bone harpoons, shell adzes; fire-drills; canoes of dugout log.

-

Barkcloth garments, ornaments of shell and bone.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Canoe routes stitched Andamans–Nicobars–Aceh; island-hop chains enabled sustained presence.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Rock art and symbolic shell use inferred; ancestor veneration may already have begun around long-lived middens.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Dual subsistence: forest hunting + marine foraging buffered climate swings.

Transition

By 7,822 BCE, Andamanasia was a canoe world of forager-islanders, firmly occupied.

Andamanasia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE) Early Holocene — Canoe Villages, Sago Groves, and Reef Harvests

Geographic and Environmental Context

Andamanasia encompasses:

-

Andaman Islands (North, Middle, South Andaman) and Nicobar Islands.

-

Aceh in northern Sumatra, with nearby islands (Simeulue, Nias, Batu, Mentawai).

-

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands.

-

The Preparis, Coco, and Little Coco Islands (off Myanmar).

Anchors: North–South Andaman coasts and reefs, Nicobar Great Channel, Aceh’s Weh Island and Lhokseumawe–Banda Aceh corridor, Simeulue–Nias–Mentawai arc, Preparis/Coco islets, Cocos (Keeling) lagoon.

-

Andamans: lush rainforest belts; estuaries at river mouths.

-

Nicobars: mangrove channels, coconut palms, breadfruit groves.

-

Aceh/Nias: forested capes, tidal flats.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Holocene optimum: warm, wet, productive reefs; monsoons stable.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Semi-sedentary canoe hamlets on Andamans/Nicobars; diets: pigs, deer, shellfish, turtle, fish, pandanus, coconut, sago.

-

Outer islands: subsistence on breadfruit, taro, reef fish.

-

Canoe traffic distributed goods, food, and kin links.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Ground-stone adzes, shell fishhooks, net weights; barkcloth; dugout canoes.

-

Early pottery may appear at Aceh’s coastal villages.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Island-hopping along the Nicobar–Andaman–Aceh arc; canoe convoys moved resin, shell, dried fish.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Ancestor shrines near canoe landings; ritual feasts at turtle nesting seasons.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Seasonal scheduling: turtle rookeries, sago harvest, yam patches buffered variability.

Transition

By 6,094 BCE, Andamanasia’s forager societies had canoe-linked resilience strategies.

Southeast Asia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Rivers of Forest, Seas of Abundance

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Early Holocene, Southeast Asia—encompassing the mainland river systems of the Irrawaddy, Chao Phraya, Mekong, and Red River, and the island worlds of the Malay Archipelago, Philippines, and eastern Indonesian seas—was a region reborn.

As postglacial seas flooded the Sunda Shelf, the coastlines of Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and the Malay Peninsula retreated to near-modern outlines, transforming river valleys into estuaries and mangrove deltas, and isolating upland populations as new islands formed.

From the rainforest interiors of Borneo and Sulawesi to the reef-fringed Nicobars and Sulu seas, the region entered an age of ecological plenty, where rising seas connected rather than divided, and rivers became arteries of settlement and exchange.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal optimum brought warm, humid, and stable monsoon conditions across tropical Asia.

-

Rainforests and mangroves expanded to their maximum historical extent.

-

Floodplains of the Mekong, Irrawaddy, and Chao Phraya rivers spread under sustained seasonal inundation, replenishing soils and fisheries.

-

Coral reefs and seagrass beds flourished in calm, nutrient-rich coastal waters.

-

Monsoons were reliable and moderate, fostering continuous forest growth and a rich mosaic of terrestrial and marine habitats.

This climatic equilibrium allowed for both forest intensification and maritime adaptation, setting the stage for Southeast Asia’s dual identity as a region of land-rooted and sea-linked societies.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across both mainland and island environments, broad-spectrum forager communities became increasingly semi-sedentary, clustering near stable water and forest edges:

-

Mainland river valleys and deltas: People lived along terraces and karst margins, combining fishing, hunting, and foraging with incipient plant tending. They harvested nuts, tubers, rice precursors (Oryza rufipogon), and pulses, along with fish, shellfish, deer, and pigs.

-

Island interiors (Borneo, Sumatra, Sulawesi): Forest foragers practiced sago and palm management, maintained tuber patches, and expanded nut collection (Canarium, Pandanus).

-

Coastal and estuarine zones: Populations exploited shellfish banks, coral reef fish, sea turtles, and mangroves, building large shell middens and seasonal fishing stations.

-

Philippines–Molucca–Sulawesi arcs: Mixed sago–taro economies combined with rich reef foraging; canoe settlements began appearing in estuarine lagoons.

These communities were not yet agriculturalists, but their deliberate replanting and niche management blurred the line between foraging and cultivation.

Technology & Material Culture

Material innovation was swift and adaptive:

-

Ground-stone adzes and axes became widespread for woodworking and forest clearance.

-

Basketry, cordage, and nets enabled efficient fishing and food transport.

-

Canoes, carved from single logs, expanded the mobility of estuarine and coastal groups, connecting rivers and islands into continuous cultural landscapes.

-

Pottery, emerging from southern China and northern Vietnam, reached the Red River delta by the end of this period, marking the earliest wave of ceramic use in mainland Southeast Asia.

-

Shell ornaments and bone tools—awls, points, hooks—appear in burial contexts, indicating social signaling and ritual activity.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The Early Holocene saw the birth of Southeast Asia’s river–sea mobility system:

-

Mainland rivers (Irrawaddy, Mekong, Red) served as internal highways, connecting highland forest foragers with coastal lagoon dwellers.

-

Maritime corridors linked the Philippines, Borneo, Sulawesi, and the Moluccas, forming early canoe routes that anticipated Austronesian seafaring millennia later.

-

The Nicobar–Andaman–Aceh arc in Andamanasia functioned as a bridge between South Asia and the Indonesian world, distributing resin, shell, and fiber goods along coasts.

Through these networks, exchange and kinship began to span entire ecological zones—forest, river, coast, and sea.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Ritual and ancestry were grounded in the land–water interface:

-

Cave burials and shelters—in Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand—yield ornaments, pigments, and bone tools, suggesting enduring ties to ancestral places.

-

Shell-midden feasting sites along coasts served as both ritual and communal arenas, marking seasonal abundance and renewal.

-

Rock art and pigment panels, depicting animals, boats, and hand stencils, continued traditions stretching back to the Pleistocene, linking memory, myth, and environment.

Spiritual life revolved around river spirits, forest abundance, and the recurring bounty of the tide.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Early Holocene Southeast Asians achieved resilience through mobility, ecosystem diversity, and multi-resource integration:

-

Seasonal shifts between upland foraging and lowland fishing buffered against monsoon variability.

-

Sago groves, nut trees, and taro patches acted as “planted insurance,” ensuring dependable yields.

-

Canoe-linked exchange distributed surpluses and resources across ecological zones.

-

Arboriculture and controlled burning maintained forest mosaics, supporting both hunting and plant management.

These strategies created a stable human–environment symbiosis, capable of absorbing climate fluctuation without crisis.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Southeast Asia had entered its Holocene equilibrium of diversity and connection.

Across river valleys, islands, and reefs, forest villagers and canoe foragers had forged economies that blended broad-spectrum subsistence with early forms of plant management and inter-island voyaging.

This epoch laid the foundations for later rice agriculture, arboriculture, and maritime exchange—systems that would turn Southeast Asia into the world’s great crossroads of land and sea.

The Early Holocene thus represents the deep beginning of the region’s ecological pluralism—a landscape where water, forest, and people learned to thrive together.

Southeast Asia's aboriginal populations may have arrived as part of the hypothesized Great Coastal Migration from Africa via coastal India.

The theory proposes that humans, likely similar to the Negritos or Proto-Australoids of modern times, arrived in the Arabian peninsula from Africa, then on the southern coastal regions of the Indian mainland, followed by spread to the Andaman Islands and modern-day Indonesia, thence branching southwards to Australia and northwards towards Japan.

Southeast Asia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Rivers, Gardens, and the Expanding Sea

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Middle Holocene, Southeast Asia—spanning the river plains of the Mekong, Chao Phraya, Irrawaddy, and Red River to the volcanic and forested archipelagos of Indonesia and the Philippines—entered a period of profound ecological and cultural integration.

Sea levels rose to near-modern highstands, transforming low-lying basins into fertile deltas and coastal plains into estuarine mosaics. The Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and Sulawesi became richly forested maritime zones surrounded by coral reefs and mangrove margins, while the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Nias–Mentawai chain formed a natural bridge between South and East Asia.

By 5000 BCE, this environment had become one of Earth’s most productive ecotones—a region of monsoon-fed fertility and maritime connectivity, where rivers and seas worked together to sustain new patterns of settlement, subsistence, and exchange.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm phase reached its full expression. Monsoon rains were abundant and dependable, swelling the great deltas and feeding rice-friendly floodplains.

In the island world to the south and east, volcanic soils remained perpetually replenished, while heavy rainfall supported dense evergreen forest and freshwater wetlands.

Coastal regions experienced dynamic shoreline change as sea-level highstands widened estuaries and drowned river mouths, creating new estuarine nurseries for fish and shellfish.

These stable, humid conditions promoted the spread of early cultivation and arboriculture, encouraging permanent settlement and interregional trade.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across mainland and island Southeast Asia, mixed economies of farming, foraging, and fishing flourished.

-

Mainland river valleys saw the first domesticated rice and millet systems, especially in the lower Mekong and Red River basins. Villages of stilted houses and ceramic storage pits emerged along levees and floodplain ridges.

-

Island Southeast Asia developed proto-horticultural systems focused on taro, yam, banana, and breadfruit, often paired with nut-bearing and fruit trees—precursors to the orchard–garden mosaics of later Austronesian culture.

-

Coastal populations relied on reef, lagoon, and mangrove fisheries, with tidal weirs and canoe-based collection of shellfish and crustaceans.

-

In Andamanasia, islanders cultivated taro and yam within forest clearings, while sustaining foraging traditions and elaborate inter-island exchange.

The result was a continuum of economies—rice-field to reef-flat, garden to mangrove—that adapted seamlessly to monsoonal rhythms.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological innovation accelerated across the region:

-

Pottery diversified into cord-marked and impressed styles, suited for cooking, storage, and ceremonial use.

-

Ground-stone adzes and barkcloth beaters signaled advanced woodworking and textile production.

-

Early spindle whorls and loom weights point to nascent weaving.

-

In the islands, outrigger and dugout canoes appeared—especially in the Philippines–Sulawesi–Molucca sphere—permitting reliable travel across channels and among islets.

-

Obsidian and stone tools moved through expanding maritime circuits, establishing the foundations of the regional trade web that would later unite Southeast Asia with Melanesia and the Pacific.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Southeast Asia became a crossroads of riverine and maritime mobility:

-

Inland routes followed the Mekong, Irrawaddy, and Red River valleys, spreading rice cultivation, stone-working, and ceramics across the mainland.

-

Coastal corridors linked the Malay Peninsula and Sumatran coasts with Java, Borneo, and the Philippines, forming a seamless maritime frontier.

-

Obsidian and shell exchange bound the Sulawesi–Molucca–Ceram–Halmahera arc to distant islands, while Andaman–Nicobar–Nias–Mentawai voyagers forged kinship alliances through canoe exchange and ritual feasts.

These movements gave rise to proto-Austronesian linguistic and cultural diffusion, the first step toward the trans-Pacific dispersals of later millennia.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Cultural life centered on ancestors, feasting, and waterborne ritual.

-

Burials in ceramic jars or stone-lined pits suggest emerging ideas of lineage and continuity.

-

Shell ornaments, beads, and spindle whorls adorned the living and accompanied the dead, expressing wealth and identity.

-

Canoe imagery—in carved prows and ceremonial markings—reflected both spiritual symbolism and practical mastery of the sea.

-

Ritual feasts, held at planting or harvest times, celebrated the unity of clan and environment, strengthening alliances across rivers and straits.

These patterns reveal an already sophisticated maritime cosmology in which water, movement, and ancestry were inseparable.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Communities maintained stability through ecological diversification. Wet-field cultivation, dry-field gardens, and fisheries complemented one another, ensuring food security amid monsoon variability.

Arboriculture protected soil fertility, while coastal mangroves and reefs absorbed storm impact. In the islands, canoe alliances functioned as social insurance, distributing surplus food and goods after floods, droughts, or volcanic events.

This adaptive flexibility produced a resilient cultural ecology, capable of absorbing environmental shocks without systemic collapse.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Southeast Asia had become a crucible of innovation—a region where horticulture, rice agriculture, pottery, textile craft, and seafaring coalesced into enduring traditions.

Mainland farmers and island navigators forged the first interlinked continental–maritime civilization, grounded in river fertility and oceanic mobility.

These centuries established the environmental, technological, and cultural foundations for the later Austronesian expansion and the complex trading societies of the Neolithic and Bronze Age tropics.

Southeast Asia thus entered history not as a periphery but as the dynamic heart of early human adaptation to land and sea—a region where agriculture met the ocean, and the canoe became civilization’s first enduring vessel.