Southeastern Asia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 1326 total

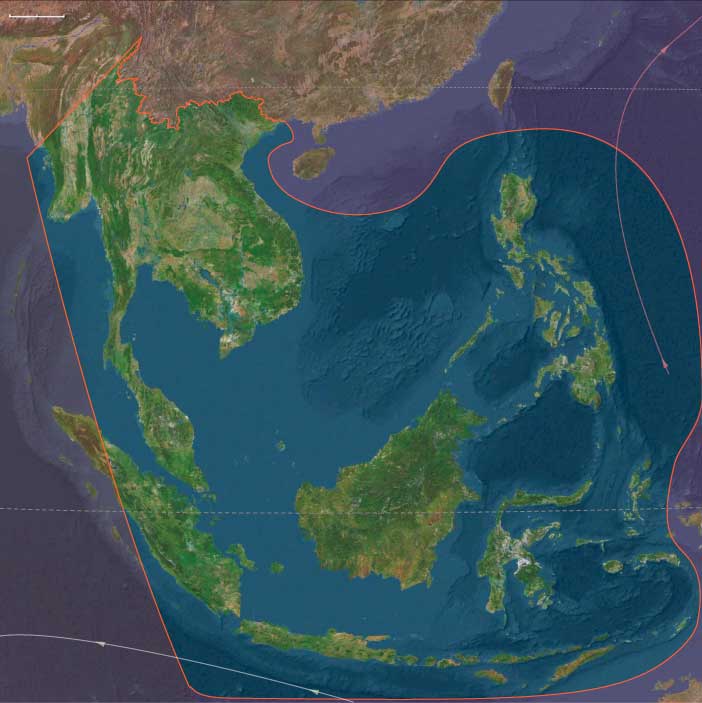

The Far East, one of the twelve divisions of the Earth, encompasses northern Australia, the entire Indonesian archipelago (excluding Aceh and Sumatra), the Philippines, the island of New Guinea, mainland Southeast Asia, the Malay Peninsula, eastern and southern China (China proper), Taiwan, the Korean Peninsula, the southern portion of the Russian Far East, and most of the Japanese archipelago, except for Hokkaido.

The southeastern boundary runs through Micronesia and Melanesia, dividing these regions into eastern and western subregions.

The northwestern boundary follows a line that separates Mongolia from China and delineates the division between Xinjiang and Tibet from China proper. It extends from its northernmost point, just beyond the northern arc of the Amur River—which marks China’s border with Russia—to its westernmost point, at the tri-border junction of Burma, India, and the Bay of Bengal.

The northeastern boundary distinguishes the extreme southern portion of the Russian Far East from the rest of the district and separates most of Hokkaido from Honshu, Kyushu, and Shikoku.

The southwestern boundary encompasses nearly all of Southeast Asia, with the exception of Aceh, which juts into the Indian Ocean and forms the southern shore of the Strait of Malacca, historically the key maritime gateway to the East.

HistoryAtlas contains 4,553 entries for The Far East from the Paleolithic period to 1899.

Narrow results by searching for a word or phrase or select from one or more of a dozen filters.

The Moderns are taller, more slender, and less muscular than the Neanderthals, with whom they share—perhaps uneasily—the Earth.

Though their brains are smaller in overall size, they are heavier in the forebrain, a difference that may allow for more abstract thought and the development of complex speech.

Yet, the inner world of the Neanderthals remains a mystery—no one knows the depths of their thoughts or how they truly expressed them.

The foundation population of the humans that today inhabit the world are the survivors of what appears to be an evolutionary bottleneck caused by a global catastrophe during the period that begins around 90,000 BCE.

The Toba supereruption (Youngest Toba Tuff or simply YTT), a supervolcanic eruption that occurs some time between sixty-nine thousand and seventy-seven thousand years ago at Lake Toba in Sumatra, Indonesia, is recognized as one of the Earth's largest known eruptions and is the most closely studied supereruption.

The related catastrophe hypothesis holds that this event plunged the planet into a six-to-ten-year volcanic winter and possibly an additional one thousand-year cooling episode.

This change in temperature results in the world's human population being reduced to ten thousand or even a mere one thousand breeding pairs, creating a bottleneck in human evolution.

Consistent with the Toba catastrophe theory, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins has postulated that human mitochondrial DNA (inherited only from one's mother) and Y chromosome DNA (from one's father) show coalescence at around one hundred and forty thousand and sixty thousand years ago, respectively.

In other words, all living humans' female line ancestry traces back to a single female (Mitochondrial Eve) at around one hundred and forty thousand years ago.

All humans can trace their ancestry with certainty via the male line back to a single male (Y-chromosomal Adam) at ninety thousand to sixty thousand years ago.

Eleven early humans, recognized as advanced members of the species Homo erectus and popularly known as Solo Man (from their grave site on a bank of the Solo River near the village of Ngandong in eastern Java, Indonesia), may have been the victims of cannibalistic activities.

Homo erectus soloensis, formerly classified as Homo sapiens soloensis, is generally now regarded as a subspecies of the extinct hominin, Homo erectus.

The only known specimens of this anomalous hominid were retrieved from sites along the Bengawan Solo River, on the Indonesian island of Java.

The remains are also commonly referred to as Ngandong, after the village near where they were first recovered.

Though its morphology was, for the most part, typical of Homo erectus, its culture was unusually advanced.

While most subspecies of Homo erectus disappeared from the fossil record roughly four hundred thousand years ago, H. e. soloensis persisted up until fifty thousand years ago in regions of Java and was possibly absorbed—or consumed—by a local Homo sapiens population at the time of its decline.

The descendants of the immigrants to West Asia who had remained in the south (or taken the southern route) had spread generation by generation around the coast of Arabia and the Iranian plateau until they reached India.

One of the groups that had gone north (east Asians were the second group) had ventured inland and radiated to Europe, eventually displacing the Neanderthals.

They had also radiated to India from Central Asia.

The former group headed along the southeast coast of Asia, reaching Australia between fifty-five thousand and thirty thousand years ago, with most estimates placing it about forty-six thousand to forty-one thousand years ago.

Sea level is much lower during this time, and most of Maritime Southeast Asia is one land mass known as the lost continent of Sunda.

The settlers probably continued on the coastal route southeast until they reached the series of straits between Sunda and Sahul, the continental land mass that was made up of present-day Australia and New Guinea.

The widest gaps are on the Weber Line and are at least ninety kilometers wide, indicating that settlers had knowledge of seafaring skills.

Archaic humans such as Homo erectus never reached Australia.

If these dates are correct, Australia was populated up to ten thousand years before Europe.

This is possible because humans avoided the colder regions of the North favoring the warmer tropical regions to which they were adapted given their African homeland.

Another piece of evidence favoring human occupation in Australia is that about forty-six thousand years ago, all large mammals weighing more than one hundred kilograms suddenly became extinct.

The new settlers were likely to be responsible for this extinction.

Many of the animals may have been accustomed to living without predators and become docile and vulnerable to attack (as will occur later in the Americas).

Some settlers cross into Australia, while others may have continued eastwards along the coast of Sunda eventually turning northeast to China and finally reaching Japan, leaving a trail of coastal settlements.

This coastal migration leaves its trail in the mitochondrial haplogroups descended from haplogroup M, and in Y-chromosome haplogroup C.

Thereafter, it may have become necessary to venture inland, possibly bringing modern humans into contact with archaic humans such as H. erectus.

Recent genetic studies suggest that Australia and New Guinea were populated by one single migration from Asia as opposed to several waves.

The land bridge connecting New Guinea and Australia became submerged approximately eight thousand years ago, thus isolating the populations of the two landmasses.

The small population of moderns had spread from the Near East to South Asia by fifty thousand years ago, and on to Australia by forty thousand years ago, Homo sapiens for the first time colonizing territory never reached by Homo erectus.

It has been estimated that from a population of two thousand to five thousand individuals in Africa, only a small group, possibly as few as one hundred and fifty to one thousand people, crossed the Red Sea.

Of all the lineages present in Africa only the female descendants of one lineage, mtDNA haplogroup L3, are found outside Africa.

Had there been several migrations one would expect descendants of more than one lineage to be found outside Africa.

L3's female descendants, the M and N haplogroup lineages, are found in very low frequencies in Africa (although haplogroup M1 is very ancient and diversified in North and Northeast Africa) and appear to be recent arrivals.

A possible explanation is that these mutations occurred in East Africa shortly before the exodus and, by the founder effect, became the dominant haplogroups after the exodus from Africa.

Alternatively, the mutations may have arisen shortly after the exodus from Africa.

Some genetic evidence points to migrations out of Africa along two routes.

However, other studies suggest that only a few people left Africa in a single migration that went on to populate the rest of the world, based in the fact that only descents of L3 are found outside Africa.

From that settlement, some others point to the possibility of several waves of expansion.