Northern Macaronesia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 66 total

The Atlantic World, a pentagonal region encompassing one twelfth of the Earth, includes the Azores, Madeira, northwestern Europe (including western Denmark and western Norway), the British Isles, the Orkney Islands, the Shetland Islands, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, Newfoundland, eastern and central North America, the northern section of Hispaniola, and several smaller island groups, notably Bermuda, the Bahamas, and the Turks and Caicos.

The eastern boundary, marked at 10° east longitude, divides Scandinavia into Eastern and Western sections, with Western Scandinavia oriented toward the North Atlantic and Eastern Scandinavia centered on the Baltic Sea Basin. This boundary also aligns with the historical eastern border of West Germany (1949–1990), before terminating in south-central Germany at its junction with the neighboring region to the southeast.

The western boundary, at 110° west longitude, cuts through Canada, separating the northern districts of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories from Alberta and Saskatchewan, approximately 75 miles south of the Alberta-Saskatchewan-Montana junction (48.1896851°N)—the northernmost point of the neighboring world to the southwest.

The southwestern boundary follows the division between the upper and lower Mississippi River Basin, then extends eastward into the Atlantic Ocean just south of Jacksonville, Florida, before terminating in northwestern Hispaniola.

HistoryAtlas contains 18,139 entries for The Atlantic World from the Paleolithic period to 1899.Narrow results by searching for a word or phrase or select from one or more of a dozen filters.

The Moderns are taller, more slender, and less muscular than the Neanderthals, with whom they share—perhaps uneasily—the Earth.

Though their brains are smaller in overall size, they are heavier in the forebrain, a difference that may allow for more abstract thought and the development of complex speech.

Yet, the inner world of the Neanderthals remains a mystery—no one knows the depths of their thoughts or how they truly expressed them.

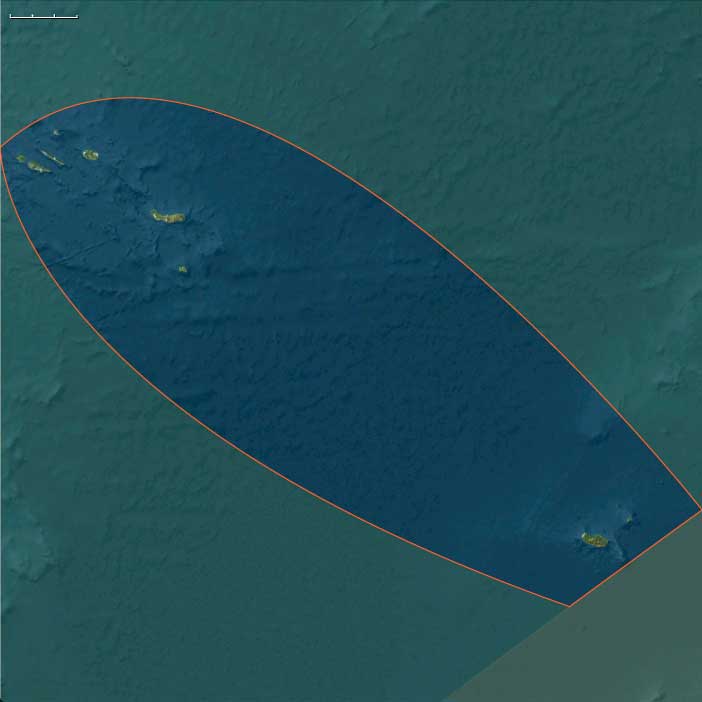

Northern Macaronesia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE) Upper Pleistocene I — Oceanic Volcanoes in the Ice Age

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northern Macaronesia includes the Azores, Madeira, Porto Santo, and the Selvagens Islands.

-

The Azores: nine volcanic islands in the mid-North Atlantic (São Miguel, Terceira, Pico, Faial, São Jorge, Graciosa, Flores, Corvo, Santa Maria).

-

Madeira Archipelago: Madeira, Porto Santo, and the uninhabited Desertas.

-

Selvagens: small rocky outcrops south of Madeira.

Anchors: Azores volcanic cones and crater lakes (Furnas, Sete Cidades), Madeira’s laurisilva-clad mountains, Porto Santo’s dunes, and Selvagens’ seabird colonies.

-

Northern Macaronesia already formed by volcanic activity, with rugged islands, sheer cliffs, and crater lakes.

-

Continental shelves absent; islands rose steeply from deep oceanic basins.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Colder Ice Age winds swept the Atlantic; sea level ~100 m lower exposed a little extra coastal shelf.

-

Islands experienced harsher winters, but fogs and rain maintained dense forests on Madeira and the Azores.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

No humans yet. Islands populated by seabirds, giant pigeons, rails, lizards, and endemic plants (e.g., Madeira laurel forest, Azorean juniper).

Technology & Material Culture

-

N/A (no humans).

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Migratory birds connected the islands to Europe and Africa; ocean currents flowed from the Gulf Stream to the Azores front.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

None, though later myths would tie the islands to Atlantis.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Ecosystems adapted to isolation, with flightless birds and large colonies of petrels.

Transition

By 28,578 BCE, Northern Macaronesia stood as untouched biotic refugia, awaiting eventual human contact.

Macaronesia (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Volcanic Refugia in the Glacial Atlantic

Geographic and Environmental Context

The Macaronesian World of the Upper Pleistocene comprised two major archipelagos—Southern Macaronesia, including the Canary Islands and Cape Verde, and Northern Macaronesia, encompassing the Azores, Madeira, Porto Santo, and the Selvagens.

Both chains rose as isolated volcanic summits from the deep Atlantic basin, positioned between Europe, Africa, and the Americas yet belonging fully to neither. Their steep bathymetric reliefs left only narrow coastal benches, while interior slopes climbed abruptly to mist-wrapped summits.

This structural duality—north humid, south arid—reveals the essence of the region’s identity in The Twelve Worlds: though grouped under one regional name, the Macaronesian archipelagos were ecologically distinct, their climates and biotas responding more to latitude, wind, and current than to one another.

Southern Macaronesia: Canary–Cape Verde Realm

-

Setting: The Canaries, lying nearest Africa, and Cape Verde, farther into the Atlantic, were both volcanic shield systems surrounded by the Canary Current and constant northeast trades.

-

Topography: High islands such as Tenerife and Gran Canaria carried deep ravines and high calderas; La Palma and El Hierro bore active faults; Fuerteventura–Lanzarote and eastern Cape Verde (Sal–Boa Vista) remained low, arid, and wind-swept.

-

Climate: During glacial times, cooler seas and a strengthened trade-wind inversion created marked aridity at low elevations but maintained fog-fed laurel forests on high, windward slopes.

-

Biota: Cloud-forest trees—Laurus azorica, Ocotea foetens—thrived above arid belts of euphorbia scrub. Seabird colonies blanketed offshore stacks; endemic reptiles, geckos, and flightless rails evolved in isolation.

-

No humans were present. Life followed the rhythms of wind, fog, and surf, unshaped by fire or clearing.

Northern Macaronesia: Azorean–Madeiran Realm

-

Setting: North of 30° N, the Azores and Madeira–Selvagens chains experienced stronger Atlantic westerlies and frequent cyclonic rains.

-

Topography: Volcanic cones, crater lakes, and laurisilva-clad ridges alternated with sheer cliffs and talus plains.

-

Climate: Though global conditions were colder, humidity remained high; fog forests persisted even through glacial droughts.

-

Biota: Dense evergreen woodland (juniper, laurel, heather) supported unique birds—giant pigeons, owls, and rails—and enormous seabird rookeries on the Selvagens.

-

Isolation: With no continental shelves, the islands stood aloof from both Europe and Africa, their species radiations paralleling, not mirroring, those of the Canaries or Cape Verde.

Climate and Environmental Dynamics

At the Last Glacial Maximum, global sea level dropped ~100 m, briefly widening each island’s coastal rim but leaving the overall geography unchanged.

-

Northern islands remained humid refugia, mild under the westerlies.

-

Southern islands oscillated between fog-forest caps and desertic lowlands as trade-wind intensity varied.

Storm tracks intensified across the mid-Atlantic, bringing winter surf and episodic rainfall but few extremes beyond those already natural to these oceanic outposts.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Only air and sea currents linked the archipelagos:

-

The Canary Current and the North Atlantic Drift swept nutrients and seeds westward.

-

Migratory birds shuttled seasonally between Europe, Africa, and these islands, transporting spores and invertebrates.

-

The islands themselves were stepping-stones for life, not for people—biological but not cultural nodes.

Cultural and Symbolic Context

To contemporary humans on the continents, Macaronesia did not exist.

The chains lay far beyond Pleistocene seafaring horizons, unimagined in myth or memory.

Later ages would cast them as Atlantis-like realms or Isles of the Blessed, but in this epoch they were purely natural sanctuaries—laboratories of evolution unobserved by human eyes.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

-

Flora: Adapted to poor soils, high winds, and fog-drip moisture; many species evolved reduced dispersal and gigantism typical of island “syndromes.”

-

Fauna: Flightless birds and reptile endemics balanced fragile yet self-sustaining food webs; seabird guano enriched thin volcanic soils.

-

Ecosystem resilience: Cycles of eruption, erosion, and recolonization fostered remarkable ecological stability despite global climatic swings.

Transition Toward the Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, the twin worlds of Macaronesia stood pristine:

-

The northern high islands blanketed in cloud forests, buffered from glacial cold by Atlantic humidity.

-

The southern shields—Canaries and Cape Verde—divided between lush fog-caps and sun-blasted coasts.

No human hand had yet touched them, yet their isolation and biotic richness made them crucial Atlantic refugia.

In the logic of The Twelve Worlds, Macaronesia demonstrates how even within one “region,” distinct subrealms evolve—each more ecologically allied to far-off worlds than to its neighboring chain—foreshadowing the layered complexity of the Holocene globe to come.

Macaronesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Pleistocene II → Early Holocene — Deglaciation, Forest Recovery, and Untouched Islands

Geographic & Environmental Context

Macaronesia—the North Atlantic’s chain of volcanic archipelagos scattered off northwestern Africa—was transformed during the long transition from the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to the Early Holocene.

The region comprised two major clusters:

-

Southern Macaronesia: the Canary Islands (Gran Canaria, Tenerife, La Palma, La Gomera, El Hierro, Fuerteventura, Lanzarote) and the Cape Verde group (Sotavento and Barlavento chains).

Here, rugged volcanic highlands (Teide, Taburiente, Fogo) contrasted sharply with low, arid shield islands such as Lanzarote and Sal–Boa Vista. -

Northern Macaronesia: the Azores, Madeira, Porto Santo, and the Selvagens Islands—younger oceanic volcanoes rising from the mid-Atlantic Ridge, with fertile slopes, crater lakes, and mist-fed forests.

During deglaciation, global sea levels rose 60–80 meters, submerging coastal benches and reshaping the islands’ outlines. New calas, coves, and cliffs formed as landslides and eruptions reworked shorelines—especially in the Canaries and Azores. Yet throughout this entire epoch, no humans had arrived. The islands’ history remained entirely ecological.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500–19,000 BCE):

Cooler and drier conditions contracted forests. In the Canaries and Madeira, montane belts shrank and lowland scrub dominated; Cape Verde became semi-arid and wind-scoured. -

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE):

Warming and increased humidity expanded laurisilva cloud forests on higher islands (Madeira, La Gomera, Tenerife) and pine–juniper woodlands on mid-altitudes; fog interception strengthened hydrology. -

Younger Dryas (c. 12,900–11,700 BCE):

A short cool, dry interval reduced montane forest area and stressed endemic flora; dune and steppe scrub advanced on lower islands. -

Early Holocene (post-11,700 BCE):

Stable warmth and strong Atlantic trades reestablished humid cloud belts; laurisilva and evergreen canopies recovered fully on Madeira, La Gomera, and Tenerife, while drought-adapted shrublands persisted on Fuerteventura, Lanzarote, and Cape Verde.

The result was a mosaic of microclimates—humid, lush peaks rising above arid lowlands—a balance that would persist into the Holocene.

Flora, Fauna, and Ecological Development

Without humans, Macaronesia evolved as an untouched ecological laboratory:

-

Flora:

• On high islands (Tenerife, Madeira, La Gomera, São Miguel): evergreen laurel forests (laurisilva) expanded, fed by fog-drip hydrology.

• Mid-elevation zones carried pine and juniper woodlands; lowlands bore thermophilous scrub, palms, and succulents.

• In Cape Verde, aridity favored acacias, euphorbs, and grasses, with isolated groves on fog-catching slopes. -

Fauna:

• Rich endemic birdlife (pigeons, finches, shearwaters), reptiles, and insects filled niches left open by the absence of mammals.

• Seabird colonies—shearwaters, petrels, and terns—nested on cliffs and islets, their guano enriching soils and driving nutrient cycles.

• Offshore waters teemed with tuna, dolphins, and sea turtles, reflecting nutrient input from upwelling and island-mass effects.

Environmental Processes and Dynamics

-

Volcanism & Erosion: Intermittent eruptions (notably on Tenerife, La Palma, Fogo) renewed soils, adding mineral fertility.

-

Sea-Level Rise: Drowned coastal terraces became wave-cut platforms, expanding marine habitats.

-

Atmospheric Circulation: Persistent trade winds and temperature inversions maintained distinct cloud belts, feeding perennial fog precipitation that sustained montane vegetation even during dry seasons.

-

Guano Feedback: Massive seabird colonies transported marine nutrients inland, sustaining forest fertility—an early model of biological recycling between sea and land.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

No human crossings occurred, but the archipelagos were ecologically interconnected by:

-

Migratory birds moving between Africa, Europe, and the mid-Atlantic.

-

Wind and current drift of seeds, pumice, and driftwood along the Canary and North Equatorial currents, occasionally linking the islands biologically to distant continents.

-

Volcanic rafting events and storm surges that redistributed soil and biota among the islands.

Cultural & Symbolic Dimensions

There was no human symbolic life here yet.

For the people of Europe and Africa, these islands lay beyond all navigational and mythic horizons—a literal “outside world” unknown to imagination. Their only “stories” were ecological: the cycles of seabird breeding, fog condensation, and forest regrowth—the silent patterns of natural continuity.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Macaronesian ecosystems displayed remarkable self-regulation and resilience:

-

Fog harvesting by evergreen canopies stabilized water budgets on high islands.

-

Successional renewal followed eruptions and slides, re-seeding disturbed ground.

-

Guano enrichment and volcanic ash maintained soil fertility.

-

Species specialization produced highly endemic floras adapted to steep ecological gradients.

Even during the Younger Dryas setback, microclimate diversity buffered these island ecologies against collapse.

Transition Toward the Holocene

By 7,822 BCE, Macaronesia had settled into a mature Holocene equilibrium:

-

Canary and Madeira laurel forests flourished once more.

-

Cape Verde’s arid landscapes supported drought-tolerant scrub and grass mosaics.

-

Azores volcanic slopes greened under high rainfall and expanding crater-lake wetlands.

-

Selvagens and low islands remained rocky sanctuaries for seabirds.

Still untouched by humans, the archipelagos stood as self-contained worlds, each with complete, functioning ecosystems—humid forests, arid scrubs, and marine oases—that would later astonish the first sailors to encounter them millennia hence.

Northern Macaronesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE) Upper Pleistocene II — Deglaciation and Expanding Forests

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northern Macaronesia includes the Azores, Madeira, Porto Santo, and the Selvagens Islands.

-

The Azores: nine volcanic islands in the mid-North Atlantic (São Miguel, Terceira, Pico, Faial, São Jorge, Graciosa, Flores, Corvo, Santa Maria).

-

Madeira Archipelago: Madeira, Porto Santo, and the uninhabited Desertas.

-

Selvagens: small rocky outcrops south of Madeira.

Anchors: Azores volcanic cones and crater lakes (Furnas, Sete Cidades), Madeira’s laurisilva-clad mountains, Porto Santo’s dunes, and Selvagens’ seabird colonies.

-

Glacial retreat and sea-level rise reshaped island coasts.

-

Laurisilva forests in Madeira and early Azores expanded as rainfall increased.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød: warmer/wetter, forests flourished.

-

Younger Dryas: brief cooling, minor contraction of forests.

-

Early Holocene: warming stabilized, producing lush evergreen canopies.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

No human settlement yet. Ecosystems dominated by birds and reptiles.

Technology & Material Culture

-

N/A.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Islands served as mid-Atlantic waypoints for migratory birds, but not for humans.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

None.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Island flora/fauna adapted to changing climate, with laurisilva stabilizing erosion and fog-fed hydrology.

Transition

By 7,822 BCE, Northern Macaronesia hosted dense forests and seabird refugia, but remained unpeopled.

Macaronesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Cloud-Forest Realms and Arid Shields at Sea’s Edge

Geographic & Environmental Context

In the Early Holocene, Macaronesia—the mid-Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores, Madeira–Selvagens, Canaries, and Cape Verde—stood as a chain of isolated volcanic worlds, each molded by orography, ocean currents, and the unbroken rhythm of trade winds.

-

Northern Macaronesia—the Azores and Madeira–Selvagens—lay in the humid temperate belt, where fog-fed laurel forests and crater-lake wetlands flourished.

-

Southern Macaronesia—the Canary and Cape Verde Islands—spanned a steep gradient from the lush cloud-forest summits of Tenerife and La Palma to the arid, wind-swept shields of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, Sal, and Boa Vista.

All remained uninhabited, connected only by ocean currents and the aerial networks of seabirds and spores.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal optimum ushered in warm, humid stability across the North Atlantic subtropics:

-

Persistent trade winds maintained orographic rainfall on windward slopes, nurturing cloud forests on high islands.

-

Leeward zones remained drier, forming semi-desert scrublands on low volcanic plains.

-

The Canary Current carried cool upwellings along the African margin, moderating temperatures and enriching marine productivity.

-

Seasonal fog interception built self-sustaining hydrological cycles, with montane forests acting as atmospheric condensers.

This climatic equilibrium yielded maximum vegetative extent and peak biodiversity across the archipelagos.

Subsistence & Settlement

No humans yet visited Macaronesia; its ecosystems evolved autonomously:

-

Northern islands (Azores, Madeira, Selvagens): dense laurisilva forests of laurel, heather, and juniper dominated uplands; crater lakes and marshes hosted invertebrate-rich wetlands; seabird colonies carpeted cliffs, fertilizing soils with guano.

-

Southern islands (Canaries, Cape Verde): strong vertical zonation developed—humid evergreen forests at mid-elevations; pine–juniper belts higher; arid steppe vegetation in lowlands. On Fogo, Santo Antão, and Santiago, fog-fed highlands contrasted sharply with desert flats on Sal and Boa Vista.

-

Coastal and islet zones teemed with penguins, petrels, shearwaters, and seals; intertidal flats supported rich mollusk beds.

Guano-driven fertility and isolation produced a living experiment in island biogeography, still untouched by human influence.

Technology & Material Culture

None. While continental neighbors advanced polished-stone and ceramic technologies, Macaronesia remained wholly pre-anthropic, its only “tools” the wind, waves, and the biological machinery of colonization.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Macaronesia was linked not by human voyages but by ecological and atmospheric exchange:

-

The Canary Current and North Atlantic Gyre circulated nutrients, driftwood, and spores.

-

Seabirds and windborne seeds bridged hundreds of kilometers between island groups, maintaining genetic flow.

-

Occasional storm-driven drift from Iberia or northwest Africa may have delivered organic material—or, conceivably, the first accidental vertebrate migrants—but sustained human navigation was millennia away.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human symbolic systems existed, yet the archipelagos themselves embodied natural metaphors of balance and contrast: the humid forests of the north against the sun-bleached shields of the south; fog as life-giver, drought as sculptor. Each island stood as an ecological shrine of self-contained renewal.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Macaronesian ecosystems perfected island resilience through ecological feedback:

-

Cloud interception and fog drip recycled atmospheric moisture into groundwater.

-

Guano enrichment and volcanic soils sustained diverse endemic floras.

-

Altitudinal zonation buffered against climate shifts: if drought struck lowlands, montane cloud belts still condensed moisture.

-

Arid-island endemics evolved succulence and deep roots, while montane species adapted to humidity and wind.

These mechanisms ensured long-term ecological stability in complete isolation.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Macaronesia had reached its Holocene ecological zenith:

-

Northern Macaronesia stood draped in cloud forests, crater-lake wetlands, and seabird rookeries of astonishing density.

-

Southern Macaronesia balanced lush volcanic summits against austere coastal deserts, each sustained by fog and seabird fertility.

-

Across all islands, life was vigorous yet untroubled, its complexity born solely of ocean, wind, and stone.

These islands—laurisilva sanctuaries in the north, volcanic fortresses in the south—would remain pristine for thousands of years more, silent witnesses to the unfolding drama of Holocene climate and the eventual spread of humankind.

Northern Macaronesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE) Early Holocene — Cloud Forests and Ocean Abundance

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northern Macaronesia includes the Azores, Madeira, Porto Santo, and the Selvagens Islands.

-

The Azores: nine volcanic islands in the mid-North Atlantic (São Miguel, Terceira, Pico, Faial, São Jorge, Graciosa, Flores, Corvo, Santa Maria).

-

Madeira Archipelago: Madeira, Porto Santo, and the uninhabited Desertas.

-

Selvagens: small rocky outcrops south of Madeira.

Anchors: Azores volcanic cones and crater lakes (Furnas, Sete Cidades), Madeira’s laurisilva-clad mountains, Porto Santo’s dunes, and Selvagens’ seabird colonies.

-

Madeira’s laurel forests reached peak extent, fed by fog condensation.

-

Azores covered with mixed forests and crater-lake wetlands.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Atlantic warm, stable rainfall. Trade winds intensified fog drip on mountain slopes.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Still no human presence. Endemic species thrived — giant pigeons, petrels, lizards, and bats.

Technology & Material Culture

-

N/A.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Ocean currents made accidental drift from Iberia or NW Africa possible, though unlikely this early.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

None.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Ecosystems reached Holocene balance, with laurisilva forests locking in soil and moisture.

Transition

By 6,094 BCE, Northern Macaronesia’s ecosystems were at their most intact.

Northern Macaronesia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE) Middle Holocene — Untouched Forest Realms

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northern Macaronesia includes the Azores, Madeira, Porto Santo, and the Selvagens Islands.

-

The Azores: nine volcanic islands in the mid-North Atlantic (São Miguel, Terceira, Pico, Faial, São Jorge, Graciosa, Flores, Corvo, Santa Maria).

-

Madeira Archipelago: Madeira, Porto Santo, and the uninhabited Desertas.

-

Selvagens: small rocky outcrops south of Madeira.

Anchors: Azores volcanic cones and crater lakes (Furnas, Sete Cidades), Madeira’s laurisilva-clad mountains, Porto Santo’s dunes, and Selvagens’ seabird colonies.

-

Islands remained isolated, forested, with rich seabird rookeries.

-

Selvagens functioned as oceanic outposts with dense colonies.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Humid, stable.

-

Minor volcanic events in the Azores reshaped local coasts.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Still no humans.

Technology & Material Culture

-

N/A.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Ocean driftwood and pumice arrived from Caribbean and Azorean volcanic eruptions.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

None.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Fauna maintained isolation adaptations — flightlessness, ground nesting.

Transition

By 4,366 BCE, ecosystems persisted in isolation and ecological equilibrium.

Macaronesia (6,093–4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Cloud Forests, Currents, and the Unseen Isles

Geographic & Environmental Context

Macaronesia—the scattered volcanic archipelagos of the Azores, Madeira, Selvagens, Canary Islands, and Cape Verde—formed a constellation of mid-Atlantic ecosystems poised between Africa, Europe, and the open ocean.

In the Middle Holocene, these islands were entirely uninhabited, their only histories written by wind, wave, and life itself.

-

The northern chains—Azores and Madeira–Selvagens—lay within the temperate influence of the North Atlantic westerlies, sustaining humid laurel forests, crater-lake wetlands, and seabird-dense coasts.

-

The southern groups—Canaries and Cape Verde—flanked the subtropical Canary Current, their climates split between moist, cloud-fed uplands (Tenerife, La Palma) and arid, trade-wind deserts (Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, Sal, Boa Vista).

Together, they were biological satellites of the African and European mainlands—stepping stones in the ocean’s gyre, each hosting a unique laboratory of evolution.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal optimum (7000–4000 BCE) brought warm, stable conditions and rising seas that stabilized coastlines near modern form.

-

The African Humid Period was fading: the Sahara and Sahel began to dry, but Canarian uplands still captured orographic mist.

-

Cape Verde, farther west and drier, entered a period of intensifying aridity, its slopes clothed in thorny scrub and drought-tolerant grasses.

-

Northern Macaronesia remained perpetually humid, wrapped in cloud belts and steady drizzle, feeding laurel forests (laurisilva) and moss-draped ravines.

Oceanographically, the Canary Current and North Atlantic Gyre maintained cool upwellings along the African coast, making nearby seas nutrient-rich and biologically explosive.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human presence marked these islands.

Ecological communities operated in self-contained equilibrium:

-

Azores & Madeira: forests of laurel, heather, and juniper blanketed volcanic plateaus and slopes; streams fed crater-lake basins teeming with algae and aquatic invertebrates.

-

Canary Islands: cloud-fed highlands nurtured dragon trees, pines, and laurels, while coasts hosted palm groves and saline scrub.

-

Cape Verde: sparse vegetation—grasses, succulents, and drought-hardy shrubs—held thin soils against erosion.

-

Across all islands, seabirds and turtles nested in vast numbers; marine mammals and pelagic fish (tuna, dolphins, whales) frequented surrounding waters.

The islands functioned as nurseries for birds, seals, and reptiles, and as rest stations for long-range migrants.

Technology & Material Culture

In this era, Neolithic societies elsewhere around the Mediterranean and North Africa mastered farming, pottery, and seafaring, but none yet crossed the Atlantic margin to Macaronesia.

The only “technologies” shaping these islands were volcanism, erosion, and the ecological machinery of colonization—wind-blown seeds, ocean-drift wood, and nutrient cycling through guano and detritus.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Though unpeopled, Macaronesia was woven into the wider Atlantic system:

-

The Canary Current and North Equatorial Countercurrent carried marine nutrients, drifting seeds, and pumice between Africa, Europe, and the Americas.

-

Migratory seabirds stitched the archipelagos together, moving nutrients and genetic material from pole to tropic.

-

Whale migrations and turtle routes paralleled these gyres, making the region one of the biological crossroads of the Atlantic millennia before human ships arrived.

These dynamic exchanges ensured that even in isolation, Macaronesia was never disconnected from the world ocean.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human culture inscribed meanings here, but the islands themselves embodied natural symbolism:

-

Cloud forests mirrored the sky’s cycles, turning mist into rain and life.

-

Turtle crawls and seabird rookeries recurred with clockwork precision, marking the seasons like ritual.

-

Volcanic renewal and forest succession created living archives of fire and rebirth—the planet’s own mythos of creation and renewal written in stone and green.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Island ecosystems demonstrated remarkable adaptive specialization:

-

Laurisilva canopies trapped moisture from passing clouds, maintaining internal hydrologies.

-

Drought-adapted shrubs and succulents dominated Cape Verde’s arid flanks, maximizing scarce rainfall.

-

Seabird colonies and turtle populations redistributed nutrients from sea to land, fertilizing soils and anchoring ecological continuity.

Disturbance—volcanic ash, storm surge, or landslide—was followed by rapid recolonization, reinforcing long-term ecological resilience.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Macaronesia stood as a fully mature Atlantic wilderness, untouched by humans yet intricately linked to planetary processes.

-

The northern archipelagos (Azores–Madeira–Selvagens) were lush, cloud-fed sanctuaries of endemic flora.

-

The southern groups (Canaries–Cape Verde) displayed the early divergence between humid and arid biomes, precursors to their modern contrasts.

-

The surrounding Canary Current system supported vast marine productivity, acting as a biological corridor for species that would later sustain seafarers.

Though unseen by human eyes, Macaronesia had already achieved its defining balance: volcanic land reborn through wind and rain, bound to the rhythms of ocean and sky—a natural prelude to the later story of navigation, colonization, and transformation.