Southern Australasia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 436 total

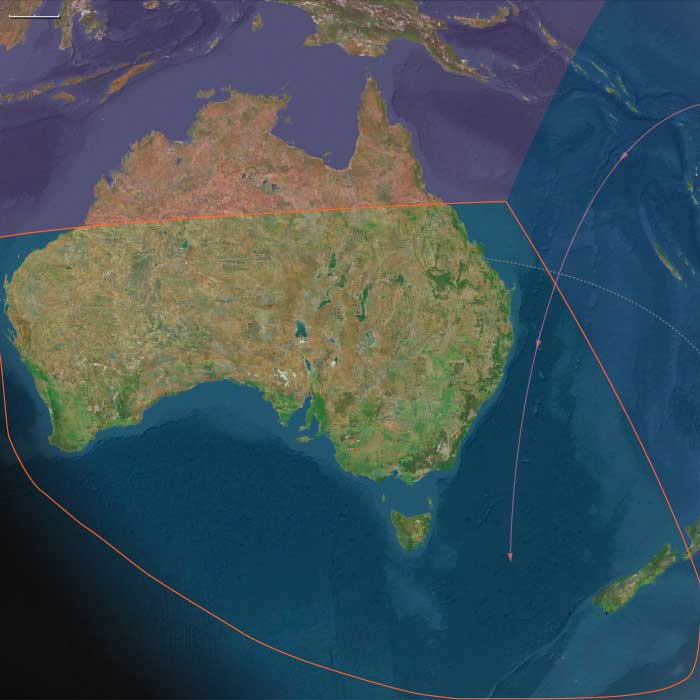

Southern Oceania encompasses Eastern East Antarctica, Tasmania, New Zealand’s South Island (including its southern coast), and Australia, extending northward to the continent’s Top End and Cape York Peninsula.

The term Australasia (French: Australasie) was coined by Charles de Brosses in Histoire des navigations aux terres australes (1756). Derived from Latin, meaning "south of Asia," the term was intended to distinguish this region from Polynesia (to the east) and the southeastern Pacific (Magellanica).

Southern Oceania’s southwestern boundary divides East Antarctica into its Western and Eastern subregions, running from the South Pole to the Kerguelen Islands. These islands, among the most remote on Earth, form part of the Kerguelen Plateau, a vast igneous geological province largely submerged beneath the southern Indian Ocean.

The French Southern and Antarctic Lands (Terres australes et antarctiques françaises)—which include Adélie Land, the Crozet Islands, the Kerguelen Islands, Amsterdam and Saint Paul Islands, and France’s Scattered Islands in the Indian Ocean—are administered as a separate district.

The southeastern boundary runs a little north of the Cook Strait, which separates New Zealand’s South Island—sometimes called the "mainland"—from the smaller yet more populous North Island (Te Ika-a-Māui).

The northern boundary divides Southern Oceania from The Far East, to which Australia’s tropical north belongs.

HistoryAtlas contains 569 entries for Southern Oceania from the Paleolithic period to 1899.

Narrow results by searching for a word or phrase or select from one or more of a dozen filters.

Australia is possibly occupied by at least 174,000 BCE (a date suggested by archaeological fieldwork in Western Australia’s Kimberley district).

The Moderns are taller, more slender, and less muscular than the Neanderthals, with whom they share—perhaps uneasily—the Earth.

Though their brains are smaller in overall size, they are heavier in the forebrain, a difference that may allow for more abstract thought and the development of complex speech.

Yet, the inner world of the Neanderthals remains a mystery—no one knows the depths of their thoughts or how they truly expressed them.

The history of indigenous Australians is thought to have spanned forty thousand to forty-five thousand years, although some estimates have put the figure at up to seventy thousand years before European settlement.

A genetic study of one hundred and eleven Aboriginal Australians, published in the journal Nature on March 8, 2017 (Aboriginal mitogenomes reveal 50,000 years of regionalism in Australia), implies that "the settlement of Australia comprised a single, rapid migration along the east and west coasts that reached southern Australia by 49–45 ka. After continent-wide colonization, strong regional patterns developed and these have survived despite substantial climatic and cultural change during the late Pleistocene and Holocene epochs. Remarkably, we find evidence for the continuous presence of populations in discrete geographic areas dating back to around 50 ka, in agreement with the notable Aboriginal Australian cultural attachment to their country.”

For most of this time, the Indigenous Australians lived as nomads and as hunter-gatherers with a strong dependence on the land and their agriculture for survival.

Only Africa has older physical evidence of habitation by modern humans.

There is also evidence of a change in fire regimes in Australia, drawn from reef deposits in Queensland, between seventy thousand years and one hundred thousand years years ago, and the integration of human genomic evidence from various parts of the world supports a date of before sixty thousand years for the arrival of Australian Aboriginal people in the continent.

Modern humans reach Australia by at least 58,000 BCE.

In 1990, a date of sixty thousand years was suggested for a rock shelter in the Northern Territory, but the finding, based on the use of a recently developed technique called thermoluminescence, is still being evaluated.

The first settlement would have occurred during an era of lowered sea levels, when there was an almost continuous land bridge between Asia and Australia, but watercraft must have been used at some points.

The descendants of the immigrants to West Asia who had remained in the south (or taken the southern route) had spread generation by generation around the coast of Arabia and the Iranian plateau until they reached India.

One of the groups that had gone north (east Asians were the second group) had ventured inland and radiated to Europe, eventually displacing the Neanderthals.

They had also radiated to India from Central Asia.

The former group headed along the southeast coast of Asia, reaching Australia between fifty-five thousand and thirty thousand years ago, with most estimates placing it about forty-six thousand to forty-one thousand years ago.

Sea level is much lower during this time, and most of Maritime Southeast Asia is one land mass known as the lost continent of Sunda.

The settlers probably continued on the coastal route southeast until they reached the series of straits between Sunda and Sahul, the continental land mass that was made up of present-day Australia and New Guinea.

The widest gaps are on the Weber Line and are at least ninety kilometers wide, indicating that settlers had knowledge of seafaring skills.

Archaic humans such as Homo erectus never reached Australia.

If these dates are correct, Australia was populated up to ten thousand years before Europe.

This is possible because humans avoided the colder regions of the North favoring the warmer tropical regions to which they were adapted given their African homeland.

Another piece of evidence favoring human occupation in Australia is that about forty-six thousand years ago, all large mammals weighing more than one hundred kilograms suddenly became extinct.

The new settlers were likely to be responsible for this extinction.

Many of the animals may have been accustomed to living without predators and become docile and vulnerable to attack (as will occur later in the Americas).

Some settlers cross into Australia, while others may have continued eastwards along the coast of Sunda eventually turning northeast to China and finally reaching Japan, leaving a trail of coastal settlements.

This coastal migration leaves its trail in the mitochondrial haplogroups descended from haplogroup M, and in Y-chromosome haplogroup C.

Thereafter, it may have become necessary to venture inland, possibly bringing modern humans into contact with archaic humans such as H. erectus.

As humans develop more advanced skills and techniques, evidence of early construction begins to emerge.

Fossil remains of Cro-Magnons, Neanderthals, and other Homo sapiens subspecies have been found alongside foundation stones and stone pavements arranged in the shape of houses, suggesting a shift toward settled lifestyles and increasing social stratification.

In addition to building on land, early humans also develop seafaring technology. The proto-Australians appear to be the first known people to cross open water to an unseen shore, ultimately peopling Australia—a remarkable achievement in early maritime exploration.

Recent genetic studies suggest that Australia and New Guinea were populated by one single migration from Asia as opposed to several waves.

The land bridge connecting New Guinea and Australia became submerged approximately eight thousand years ago, thus isolating the populations of the two landmasses.

The small population of moderns had spread from the Near East to South Asia by fifty thousand years ago, and on to Australia by forty thousand years ago, Homo sapiens for the first time colonizing territory never reached by Homo erectus.

It has been estimated that from a population of two thousand to five thousand individuals in Africa, only a small group, possibly as few as one hundred and fifty to one thousand people, crossed the Red Sea.

Of all the lineages present in Africa only the female descendants of one lineage, mtDNA haplogroup L3, are found outside Africa.

Had there been several migrations one would expect descendants of more than one lineage to be found outside Africa.

L3's female descendants, the M and N haplogroup lineages, are found in very low frequencies in Africa (although haplogroup M1 is very ancient and diversified in North and Northeast Africa) and appear to be recent arrivals.

A possible explanation is that these mutations occurred in East Africa shortly before the exodus and, by the founder effect, became the dominant haplogroups after the exodus from Africa.

Alternatively, the mutations may have arisen shortly after the exodus from Africa.

Some genetic evidence points to migrations out of Africa along two routes.

However, other studies suggest that only a few people left Africa in a single migration that went on to populate the rest of the world, based in the fact that only descents of L3 are found outside Africa.

From that settlement, some others point to the possibility of several waves of expansion.