Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 29 total

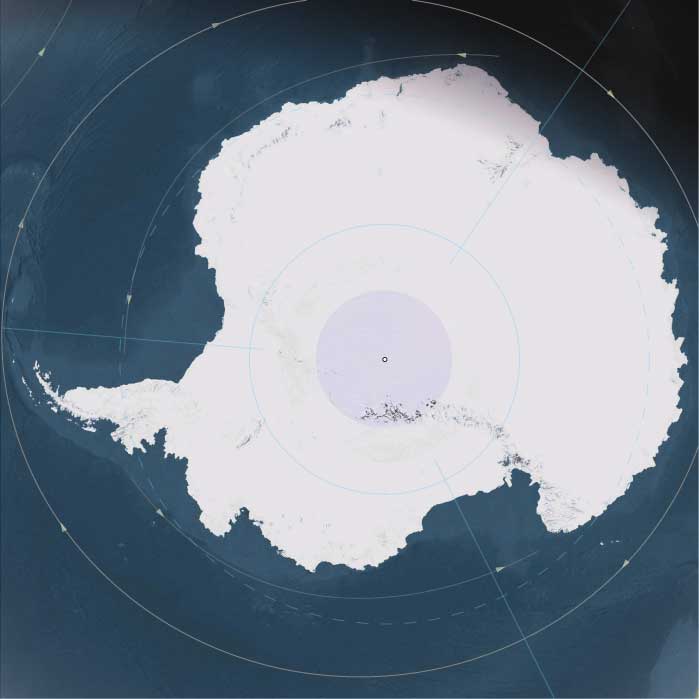

Southern Oceania encompasses Eastern East Antarctica, Tasmania, New Zealand’s South Island (including its southern coast), and Australia, extending northward to the continent’s Top End and Cape York Peninsula.

The term Australasia (French: Australasie) was coined by Charles de Brosses in Histoire des navigations aux terres australes (1756). Derived from Latin, meaning "south of Asia," the term was intended to distinguish this region from Polynesia (to the east) and the southeastern Pacific (Magellanica).

Southern Oceania’s southwestern boundary divides East Antarctica into its Western and Eastern subregions, running from the South Pole to the Kerguelen Islands. These islands, among the most remote on Earth, form part of the Kerguelen Plateau, a vast igneous geological province largely submerged beneath the southern Indian Ocean.

The French Southern and Antarctic Lands (Terres australes et antarctiques françaises)—which include Adélie Land, the Crozet Islands, the Kerguelen Islands, Amsterdam and Saint Paul Islands, and France’s Scattered Islands in the Indian Ocean—are administered as a separate district.

The southeastern boundary runs a little north of the Cook Strait, which separates New Zealand’s South Island—sometimes called the "mainland"—from the smaller yet more populous North Island (Te Ika-a-Māui).

The northern boundary divides Southern Oceania from The Far East, to which Australia’s tropical north belongs.

HistoryAtlas contains 569 entries for Southern Oceania from the Paleolithic period to 1899.

Narrow results by searching for a word or phrase or select from one or more of a dozen filters.

Antarctica (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — The Frozen Continent and Its Oceanic Halo

Geographic and Environmental Context

During the height of the Late Pleistocene, Antarctica stood as the coldest, driest, and most isolated world on Earth—a continent sealed in ice and girdled by the Southern Ocean.

The great landmass divided naturally into three broad realms:

-

East Antarctica, the immense polar plateau rising more than 3 km above sea level, draped in ice more than 4 km thick and stretching from the Transantarctic Mountains to the Indian Ocean rim.

-

West Antarctica, a lower, fractured terrain comprising the Antarctic Peninsula, Marie Byrd Land, and the Amundsen–Ross embayments, fringed by vast floating shelves.

-

The subantarctic ring—the nearby island arcs of South Georgia, the South Orkneys, the South Sandwich Islands, Bouvet, and the Prince Edward–Marion chain—sat just beyond the continental ice but within its climatic orbit, forming Antarctica’s ecological frontier with the world’s oceans.

These divisions—polar plateau, continental rim, and subantarctic ring—behaved less like a single geography than like three interconnected systems whose unity was maintained by ice, wind, and current.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The period between 49,000 and 28,500 BCE encompassed the build-up to the Last Glacial Maximum.

-

Temperature: Mean annual values across the plateau were 10–15 °C colder than today; coastal sectors remained below freezing even in summer.

-

Ice extent: The East Antarctic Ice Sheet thickened and spread toward the coast, while the smaller West Antarctic ice masses merged, grounding on the continental shelf. Overall, Antarctica’s ice volume reached its greatest Quaternary extent.

-

Sea level: Global levels fell ~120 m, exposing continental shelves and expanding grounded ice.

-

Atmosphere: Lower greenhouse-gas concentrations and stronger katabatic winds intensified polar deserts in the interior.

-

Ocean: Sea-ice fronts advanced far north in winter, yet polynyas—open-water oases—persisted along parts of the coast, sustaining remarkable marine productivity.

The result was a planet tipped toward cold equilibrium: Antarctica at its broadest and most luminous, radiating sunlight back into space and anchoring global climate.

Flora, Fauna, and Ecology

Antarctica itself supported only microbial, algal, and cryptogamic life confined to small ice-free niches, while its surrounding seas and subantarctic islands hosted some of Earth’s richest cold-water ecosystems.

-

Terrestrial oases: Along the Dry Valleys, the Antarctic Peninsula, and scattered nunataks, thin melt-season films supported cyanobacteria, mosses, lichens, and minute invertebrates.

-

Coastal wildlife: Adélie and early emperor-penguin lineages bred on stable sea-ice platforms; skuas and petrels nested on rocky ledges.

-

Marine systems: Krill, copepods, and under-ice algae flourished beneath seasonal pack ice, feeding whales, seals, and seabirds.

-

Subantarctic ring: Islands like South Georgia and the Prince Edward group carried tussock grass, moss, and sprawling rookeries of albatrosses, petrels, and fur seals—vital nodes in the circum-polar web.

Though barren by continental standards, Antarctica’s margins were alive with motion, its biological clock synchronized to the annual advance and retreat of ice.

Human Presence and Global Context

No humans had ever set foot on this continent or its islands.

Elsewhere, Homo sapiens spread across Africa, Eurasia, and Sahul, but Antarctica lay far beyond the technological reach of any Pleistocene mariner.

Its isolation rendered it the world’s ultimate terra incognita, absent even from myth.

Yet indirectly, it mattered: the continent’s albedo, sea-ice cycles, and carbon sequestration steered the climates within which human civilizations would one day arise.

Antarctica was already humanity’s silent climate engine.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Though devoid of people, the region was a crossroads for wind, current, and life:

-

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) encircled the continent, connecting the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans into a single conveyor.

-

The westerly wind belt (“roaring forties” – “furious fifties”) drove surface circulation and upwelling that fed krill blooms.

-

Whales, seals, and seabirds migrated along these highways from every southern continent, forming a truly circum-global ecological network.

These corridors prefigured the pathways of future exploration, commerce, and science.

Symbolic and Conceptual Role

In human terms, Antarctica existed only as an absence—a mythic void beyond any known horizon.

Had Ice-Age peoples imagined it, it might have represented the under-world of ice, a place where sun and earth froze in perpetual night.

In geological reality, it was the earth’s mirror, reflecting heat and regulating balance: a physical metaphor for stasis at the edge of creation.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Antarctica’s ecosystems, though sparse, showed immense stability:

-

Glacial resilience: Microbial and moss communities endured multiple glacial advances, recolonizing from refugia during brief interstadials.

-

Marine adaptation: Krill and fish species evolved antifreeze proteins, surviving under permanent cold.

-

Carbon storage: Ice-sheet expansion sequestered atmospheric CO₂, tightening Earth’s glacial grip yet ensuring reversibility when melting resumed.

In every process—wind, ice flow, nutrient recycling—the system demonstrated the capacity of life and climate to adapt through feedback and equilibrium.

Transition Toward the Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, Antarctica had reached near-peak glacial extent.

The East Antarctic plateau remained unaltered in its frozen dominion; the West Antarctic shelves thickened; and the subantarctic islands thrived as refugia for the Southern Ocean’s living abundance.

Humanity still knew nothing of this world, yet its influence touched every other: it cooled the tropics, lowered the seas, and sculpted the very margins of habitable Earth.

In the grand pattern of The Twelve Worlds, Antarctica stood as the still point of the planet’s climatic wheel—its icy heart, unseen but omnipresent, binding the glacial age together.

Antarctica (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Pleistocene II → Early Holocene — Ice, Ocean, and the Edges of Life

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the transition from the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to the Early Holocene, Antarctica remained a continent of deep ice and shallow change—a frozen core slowly responding to planetary warming.

Its three major regions reflected stark gradients of cold, wind, and ecological possibility:

-

Eastern East Antarctica — the vast polar plateau rising over 3,000 m, capped by ice up to 4 km thick and rimmed by the Amery, Shackleton, and Ross Sea shelves. A hyper-arid interior where snow accumulation was minimal and temperatures rarely rose above –40 °C.

-

Western East Antarctica — the coastal fringe along the Indian and Atlantic sectors and its subantarctic island arc (South Georgia, South Sandwich, South Orkney, Bouvet, Prince Edward–Marion, western Kerguelen). Cold, wet, and windy, these islands were the biological outposts of the polar world.

-

West Antarctica — including the Antarctic Peninsula, Ellsworth Mountains, Marie Byrd Land, and the great Ross and Filchner–Ronne shelves. Ice streams here flowed into subpolar embayments, while geothermal oases and ice-free headlands supported sparse but persistent life.

Together they formed a mosaic from permanent polar desert to storm-lashed tundra, all encircled by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC)—the engine linking the Southern Ocean to every other sea.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500 – 19,000 BCE):

The Antarctic Ice Sheet was thicker and broader than today. Ice shelves reached the continental-shelf edge; sea ice expanded hundreds of kilometers northward each winter. Mean annual temperatures were 6–10 °C colder than modern values. -

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700 – 12,900 BCE):

Global warming marginally softened coastal climates. Seasonal sea ice contracted slightly in summer, exposing rocky beaches for brief biological colonization. -

Younger Dryas (c. 12,900 – 11,700 BCE):

Cooling restored extensive winter sea ice; outlet glaciers paused or advanced; westerly winds strengthened. -

Early Holocene (post-11,700 BCE):

Renewed warmth reduced ice extent along the Antarctic Peninsula and Ross–Amundsen coasts; polynyas widened; ice-free ground on subantarctic islands expanded. Interior East Antarctica remained effectively unchanged—still the planet’s coldest desert.

Flora, Fauna & Ecology

Life was confined to coastal oases, volcanic slopes, and the surrounding seas:

-

Mainland Antarctica:

• Lichens, mosses, and microbial mats in ice-free pockets near geothermal sites and rocky headlands.

• Adélie and early Emperor penguins nesting on stable fast-ice or gravel beaches.

• Weddell, leopard, and crabeater seals using tide cracks and polynyas for breeding. -

Subantarctic islands:

• Tundra vegetation—tussock grasses, mosses, and cushion plants—spread on newly deglaciated slopes.

• Immense rookeries of albatrosses, petrels, penguins, and fur or elephant seals.

• Peat initiation began in saturated hollows, creating long-term carbon sinks. -

Marine realm:

• Seasonal phytoplankton blooms at the ice edge supported vast krill swarms, anchoring the food web for whales, seals, and seabirds.

• Nutrient-rich upwelling sustained the Southern Ocean as Earth’s most productive cold-water ecosystem.

Human Presence

None.

Antarctica remained completely beyond the reach of late Pleistocene navigation and survival technology. Its existence was outside any cultural geography or mythic horizon.

Environmental Dynamics

-

Ice-flow systems transported snow from the plateau to the sea, feeding the great shelves.

-

Calving and polynyas drove marine productivity by mixing surface and deep waters.

-

Volcanism in Marie Byrd Land, the South Shetlands, and South Sandwich arc created minor geothermal refuges that harbored unique biota.

-

Subantarctic feedback loops: guano deposition, peat formation, and storm redistribution of nutrients knit ocean and land into one biogeochemical engine.

Symbolic & Conceptual Role

For every human society of this time, Antarctica did not yet exist—not as rumor, myth, or destination. It was a planetary absence, sensed only through distant weather and current systems that touched Africa, South America, and Australasia.

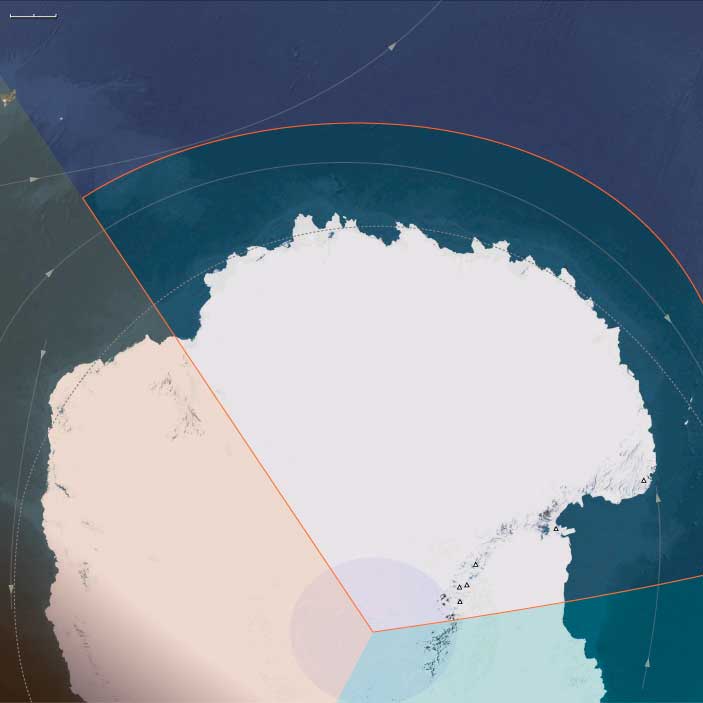

Eastern East Antarctica (28557 – 7822 BCE): The Polar Plateau’s Eastern Expanse

Geographic and Environmental Context

Eastern East Antarctica—stretching from the Ross Sea sector eastward past the Amery Ice Shelf toward the Australian Antarctic Territory—is dominated by the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, the largest single ice mass on Earth.

-

The interior rises over 3,000 meters above sea level, with ice thickness reaching up to 4 km.

-

Coastal margins are fringed by floating ice shelves, ice cliffs, and occasional rocky nunataks.

-

Katabatic winds sweep from the polar plateau toward the coast, scouring snow and creating vast sastrugi fields.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500 – 19,000 BCE): Already the coldest region on Earth, Eastern East Antarctica experienced intensified cold, reduced snowfall, and ice sheet expansion along some coastal fringes. The interior remained a hyper-arid polar desert.

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700 – 12,900 BCE): Global warming was detectable only at the coastal periphery—slight retreat of sea ice in summer months, but the interior climate remained well below freezing year-round.

-

Younger Dryas (c. 12,900 – 11,700 BCE): No significant interior change, but seasonal sea ice extended slightly further offshore in winter.

-

Early Holocene (after c. 11,700 BCE): Some coastal ice shelves experienced minor retreat, and limited ice-free ground expanded in rare Antarctic oases and rocky headlands, briefly supporting mosses, lichens, and microbial mats.

Flora, Fauna, and Ecology

Life was almost entirely restricted to the coastal margins and offshore waters:

-

Adélie penguins and early forms of Emperor penguins bred on rocky beaches and stable fast ice.

-

Seals—Weddell, leopard, and crabeater—hauled out on ice edges for breeding and resting.

-

Seasonal phytoplankton blooms in surrounding waters supported krill, fish, and seabirds such as petrels and skuas.

-

On the few exposed rocky oases, microbial mats, mosses, and lichens persisted in summer.

Human Presence

-

During this epoch, no humans had reached Eastern East Antarctica. Extreme cold, remoteness, and pack ice barriers kept the continent far beyond the reach of late Pleistocene maritime technology.

-

The region existed entirely outside human conceptual geography and oral tradition at the time.

Environmental Dynamics

-

Ice movement flowed from the high polar plateau toward the coast, feeding ice shelves like the Amery and Shackleton.

-

Coastal polynyas—areas of open water in sea ice—were crucial wintering and feeding zones for marine mammals and birds.

-

Occasional katabatic wind storms sculpted ice surfaces and redistributed snow.

Symbolic and Conceptual Role

For human societies of this period, this land was an unknown polar void—geographically real but unimagined in any cultural mapping of the world.

Transition Toward the Holocene

By 7822 BCE, Eastern East Antarctica’s vast ice sheet remained largely unchanged in extent from the LGM, though subtle coastal retreats and seasonal productivity increases in the surrounding Southern Ocean were underway. It would remain unvisited by humans for many thousands of years.

Antarctica (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Ice Retreat, Blue Shadows, and the Rebirth of Polar Life

Geographic & Environmental Context

In the Early Holocene, Antarctica was a continent in transition—from the crushing grip of the last glacial maximum toward the cold equilibrium that would define the modern world.

The East Antarctic Ice Sheet remained massive and largely stable, locked high across the polar plateau.

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet, however, was in full retreat: ice fronts pulled back across the Ross and Weddell embayments, and outlet glaciers in the Amundsen Sea sector began their long withdrawal.

Ice-free oases and mountain ridges—Bunger Hills, McMurdo Dry Valleys, Larsemann Hills, and portions of the Antarctic Peninsula—expanded modestly, exposing ancient moraines, saline lakes, and tundra-like niches.

Around the margins, the Southern Ocean encircled the continent as a restless engine—driven by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC)—linking it ecologically to the subantarctic islands of the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal maximum brought slight but critical warming to the polar realm:

-

Mean annual temperatures rose by a few degrees compared to the Late Glacial period.

-

Ice-sheet thinning occurred along coasts and embayments; major ice shelves (Ross, Filchner–Ronne, Amery) receded inland from their glacial maxima but remained expansive.

-

Sea ice diminished seasonally, producing longer open-water summers; polynyas (persistent open-water zones) formed near coasts.

-

Moisture transport from mid-latitude storms increased snowfall in coastal sectors, while the interior remained hyper-arid and katabatic-wind-swept.

The Antarctic atmosphere, once dominated by glacial cold, now cycled through new seasonal pulses of thaw, meltwater, and refreeze—introducing rhythm to a continent that had long known only permanence.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human beings had yet set foot on the Antarctic continent.

Life here was purely non-human, yet in its own way as adaptive and dynamic as any civilization:

-

Coastal tundra oases supported mosses, lichens, and microbial mats, expanding in meltwater-fed basins and rock fissures.

-

Seabirds and penguins (Adélie, gentoo, chinstrap) colonized ice-free shores, while petrels, skuas, and cormorants nested along the Antarctic Peninsula.

-

Seals (Weddell, leopard, and elephant) established new haul-outs on beaches newly exposed by ice retreat.

-

Offshore ecosystems surged with life: krill, squid, fish, and plankton fed vast congregations of whales returning to the high-latitude feeding grounds each summer.

This was the rebirth of the polar food web—a return of productivity after millennia of glacial austerity.

Technology & Material Culture

In the human world elsewhere, people were perfecting pottery, domesticating animals, and building the first agricultural villages—but Antarctica remained untouched.

No hearth, no track, no artifact broke its frozen solitude; the continent’s only “technology” was that of ice, wind, and wave shaping the living crust of sea and shore.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Biological movement replaced any human route:

-

The ACC circled Antarctica as a constant conveyor, carrying nutrients, plankton, and larvae around the planet’s southern girdle.

-

Migratory whales followed the seasonal sea-ice edge, feeding in austral summers and migrating north in winter.

-

Seabirds linked Antarctica to the subantarctic islands, bridging thousands of kilometers.

-

Oceanic fronts—the Polar and Subantarctic convergences—acted as invisible highways of life, defining productivity gradients that tied Antarctica to every southern ocean.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human culture existed here to interpret its grandeur, yet natural symbolism flourished:

-

The cyclic return of sunlight, the waxing and waning of ice, the rhythm of migration and reproduction—all wrote an ecological cosmology of recurrence and endurance.

-

Each year’s melt renewed the promise of life; each winter’s freeze sealed it again in blue ice and silence.

Antarctica, though empty of people, was alive with rituals of nature: nesting cycles, whale migrations, the return of krill swarms, the annual exchange of heat and light.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Life clung to margins and adapted ingeniously to extremes:

-

Microbial and algal mats developed antifreeze proteins and pigments to withstand freeze–thaw cycles.

-

Seabirds and seals synchronized breeding to brief ice-free seasons.

-

Krill populations adapted to feed beneath thinning sea ice, ensuring continuity of the entire food chain.

-

Vegetation and soil microbes colonized wind-sheltered microhabitats, enriching them over centuries.

Antarctica’s ecosystems achieved a delicate equilibrium—resilient, self-renewing, and finely tuned to the planet’s most unforgiving climate.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Antarctica had reached its Holocene form:

-

Ice sheets largely stabilized within modern bounds; ice-free oases persisted as scattered sanctuaries of life.

-

Marine productivity and migratory cycles reached full vigor, fueling the great southern food web.

-

The continent’s pristine ecosystems remained untouched, awaiting future ages when humankind would finally seek them out.

At the dawn of the Holocene, Antarctica was both a remnant of the glacial past and a promise of planetary renewal—the white mirror of Earth’s resilience, where wind, sea, and sunlight rehearsed the rhythm of life long before human memory.

Antarctica (6,093–4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Retreating Ice and Expanding Life at the Edge of the World

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Middle Holocene, Antarctica stood at its largest ice extent since the Pleistocene but was steadily retreating toward its modern boundaries.

The East Antarctic Ice Sheet remained massive and stable, capped by the polar plateau, while the West Antarctic Ice Sheet continued its slow recession along the Ross and Amundsen sectors.

Major ice shelves (Ross, Filchner–Ronne, Amery) persisted but had withdrawn slightly from their glacial highstand margins.

Isolated oases and rock outcrops—the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Bunger Oasis, Larsemann Hills, and ice-free ridges of the Antarctic Peninsula—expanded to reveal saline lakes, weathered moraine, and patches of barren tundra.

Surrounding seas—the Ross, Weddell, Bellingshausen, and Amundsen—were alive with seasonal ice, polynyas, and nutrient-rich upwellings that tied Antarctica to the Southern Ocean biosphere.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm interval (roughly 7,000–4,000 BCE) brought temperatures 1–2 °C higher than later millennia.

-

Coastal regions experienced longer ice-free summers and reduced sea-ice extent.

-

Moisture transport from lower latitudes increased, yielding more snow on the coastal fringe and less in the interior.

-

Persistent katabatic winds and the polar high pressure kept the central plateau hyper-arid.

-

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) remained strong, driving productivity in marginal seas and sustaining dense krill populations.

Overall, Antarctica entered a period of relative climatic equilibrium—cold, but biologically vibrant along its edges.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human occupation touched the continent at this time.

Instead, its shorelines and oases were colonized by life returning after glacial retreat:

-

Coastal tundras harbored mosses, liverworts, lichens, and microbial mats around melt-water streams and saline lakes.

-

Seabirds (petrels, skuas) nested on ice-free headlands; Adélie and gentoo penguins established small colonies along peninsula beaches.

-

Seals (fur, elephant, leopard, Weddell) hauled out on newly exposed coasts.

-

Offshore, krill blooms and phytoplankton carpets fed whales, fish, and squid.

The continent’s biosphere remained concentrated within a narrow coastal margin where sea and ice met.

Technology & Material Culture

Human technological horizons elsewhere had advanced to pottery and early metallurgy, but Antarctica lay far beyond navigation and survival limits.

No boats, clothing, or fuel systems of the period could sustain occupation in its polar environment.

All evidence of activity remains geophysical and biological, not archaeological.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Ecological flows replaced human traffic.

-

The ACC linked Antarctic waters to the South Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans, circulating nutrients and organisms.

-

Seasonal sea-ice advance and retreat regulated migration cycles for whales, seals, and birds.

-

Polynyas (open-water windows within ice fields) served as oases of productivity, feeding ground for penguins and marine mammals.

-

Airborne transport of dust and pollen from southern continents subtly altered Antarctica’s chemical and biological makeup.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human culture yet existed to assign meaning to this land. Its symbolism was entirely natural—the recurrence of seasons, the calving of icebergs, and the cyclic arrival of migrants defined time and memory for the biosphere.

In the absence of human observers, Antarctica embodied pure process: the planet’s own ritual of freeze and renewal.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience was structural and biological:

-

Krill and plankton adjusted to changing ice algae cycles, ensuring continuity through cold fluctuations.

-

Microbial and plant colonies regenerated rapidly after freeze–thaw disturbances.

-

Seabird and seal populations shifted colonies with ice margin movements.

-

Glacial and volcanic feedbacks cycled nutrients through soil and sea, maintaining a delicate but productive equilibrium.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Antarctica had entered a mature Holocene state: glaciers largely stable within modern margins, ice-free oases expanding slowly, and coastal ecosystems fully established.

Although no human had yet seen it, Antarctica already functioned as the planet’s climatic and biological keystone—regulating global ocean circulation and anchoring the world’s southern food chains.

It was, and remains, Earth’s most elemental continent: a mirror of climate balance, a repository of ice and light, and a stage awaiting future voyagers.

Antarctica (4,365 – 2,638 BCE): Late Holocene — Retreating Ice and Life at the Margins

Geographic & Environmental Context

During this epoch, Antarctica remained a vast ice-bound continent surrounded by dynamic seas and drifting pack ice. The East Antarctic Ice Sheet—thick and stable—still crowned the polar plateau, while the West Antarctic sector had largely stabilized following mid-Holocene deglaciation pulses.

Major ice shelves—the Ross, Filchner-Ronne, and Amery—stood near their modern outlines. Ice-free enclaves such as the Dry Valleys of Victoria Land, Larsemann Hills, and Bunger Oasis broadened slightly, exposing glacial till and saline lakes. Along the Antarctic Peninsula, retreating glaciers opened narrow coastal plains and nunatak ridges that hosted emerging tundra and moss communities.

Surrounding seas—Weddell, Ross, Amundsen, and Bellingshausen—remained vital engines of global climate regulation, circulating cold, nutrient-rich waters through the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC).

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The mid-Holocene warmth reached its southern expression during this interval. Mean temperatures were 1–2 °C warmer than late-Holocene averages, driving minor ice-margin retreat but leaving the continental interior near thermal equilibrium.

Sea ice extent contracted seasonally, generating large summer polynyas rich in plankton. Moisture transport from lower latitudes increased snowfall on coastal slopes even as katabatic winds kept the polar plateau hyper-arid.

By the later third millennium BCE, the regional climate began a slow transition toward cooler, more variable conditions, setting the stage for the Neoglacial advance of later millennia.

Biotic Communities and Ecosystems

No humans had yet reached the Antarctic realm. Life was concentrated in maritime and ice-free margins:

-

Coastal tundra patches supported mosses, liverworts, algae, and microbial mats.

-

Seabird rookeries (petrels, skuas) and seal colonies established on exposed capes and beaches of the Peninsula and offshore islands.

-

Krill blooms thrived in nutrient-rich upwellings, feeding baleen whales, penguins, and fish.

-

Inland oases hosted cyanobacterial mats and extremophile microorganisms within hypersaline lakes, forming self-contained ecosystems.

These biological networks expanded during warm centuries, retreating when snow accumulation or ice advance encroached.

Technology & Material Culture

Elsewhere on the planet, Neolithic societies were inventing metallurgy and long-distance trade; none of this touched Antarctica. The continent remained beyond human reach, its story told only through geological and biological processes.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The ACC and coastal polynyas created seasonal belts of productivity encircling the continent. Migratory whales, seals, and seabirds linked Antarctica to the South Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans, transporting nutrients across hemispheres. Drifting icebergs carried sediments and microorganisms far north, seeding marine ecosystems and influencing ocean chemistry on a planetary scale.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

There were no human symbols or rituals in Antarctica at this time. Its enduring cycles—the annual expansion and retreat of sea ice, the rhythmic calls of penguin colonies, the calving of glaciers into the Southern Ocean—formed the planet’s natural symphony of recurrence and renewal.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Antarctic ecosystems demonstrated resilience through flexibility:

-

Species synchronized breeding and molting to short summer productivity windows.

-

Krill populations adapted to fluctuations in sea-ice algae cover.

-

Microbial mats regenerated rapidly after freeze–thaw disturbance.

Physical systems—ice shelves, polynyas, katabatic wind zones—maintained a dynamic equilibrium balancing accumulation and ablation.

Long-Term Significance

By 2,638 BCE, Antarctica had achieved a mature Holocene stability. Ice volumes approximated modern levels; tundra and marine ecosystems were fully established within their climatic niches. Though unvisited by humankind, the continent already acted as a regulator of global oceanic and atmospheric circulation—its winds, ice, and currents shaping climates across the southern hemisphere. In this deep prehistory, Antarctica stood as a pristine mirror of Earth’s environmental balance: frozen, living, and profoundly interconnected.

Antarctica (2637 – 910 BCE): The Ice Plateau and the Living Margins

Regional Overview

In Early Antiquity, the Antarctic realm was a planet unto itself — a continent of glacial silence, rimmed by life-rich seas and subantarctic refuges.

Across the age of bronze and early iron elsewhere, Antarctica remained unpeopled, unseen, and unimagined.

Yet its climate rhythms, ocean currents, and seasonal productivity already shaped the biospheric balance of the southern hemisphere.

From the frozen plateaus of East Antarctica to the storm-wracked islands of the Scotia Arc and subantarctic belts, the region functioned as Earth’s ultimate frontier of wind, ice, and oceanic life.

Geography & Climate

Antarctica’s physical duality was already pronounced:

-

East Antarctica — a massive, stable shield buried beneath more than three kilometers of ice, crowned by domes exceeding 3,000 m in elevation.

-

West Antarctica — a chain of lower marine basins, ice domes, and the long finger of the Antarctic Peninsula projecting toward South America.

Across both, climate was hyper-polar:

-

Interior temperatures fell below –60 °C in winter; katabatic winds scoured snow from the slopes.

-

Summer brought continuous daylight along coasts, minor melting at exposed oases, and marine polynyas that pulsed with plankton blooms.

-

Annual precipitation was minimal — millimeters of water equivalent over the plateau — but coastal snow accumulation fed glaciers that surged toward the sea.

Eastern East Antarctica: The Polar Plateau’s Eastern Expanse

From the Ross Sea to the Amery Ice Shelf, the vast plateau remained a world of frozen calm.

Its katabatic winds carved snow dunes and shaped the desert of ice; its glaciers fed the largest ice shelves on Earth.

Life existed only at the margins — microbial mats in coastal oases, Adélie and early Emperor penguins nesting on summer ice, and seals resting along stable leads.

For humans, it was beyond imagination: a realm unseen, unreachable, and unknown.

Western East Antarctica: Icebound Shores and Subantarctic Refuges

East Antarctica’s outer arc merged seaward into a chain of subantarctic islands — South Georgia, the South Sandwiches, Bouvet, the South Orkneys, and the Prince Edward–Marion and western Kerguelen groups.

Here, in the westerly wind belt, marine life flourished under constant gales:

-

Penguin and albatross colonies blanketed every ice-free slope.

-

Seals and whales followed dense krill fields around volcanic and glaciated coasts.

These islands were far milder than the continental interior, sustaining tussock grasslands, mosses, and lichensnourished by guano and rainfall.

They were the only true oases of warmth and biological abundance within the Antarctic system.

West Antarctica: Fragmented Ice Lands and Coastal Wildlife Havens

Across the Antarctic Peninsula and the Amundsen–Bellingshausen Seas, the continent fractured into smaller ice domes and marine basins.

Here, seasonal melting created ice-free headlands that hosted dense Adélie and gentoo penguin rookeries, petrel colonies, and seal haul-outs.

Peter I Island, a volcanic outlier adrift in the Bellingshausen Sea, mirrored this pattern on a miniature scale — an isolated rock fortress used seasonally by seabirds and seals.

These shores marked the northernmost limit of the polar continent, where sunlight and upwelling met to generate the most productive waters of the Southern Ocean.

Ecological Systems & Biological Productivity

The Antarctic ecosystem revolved around a single seasonal pulse:

-

Spring–Summer: Melting sea ice released nutrients, triggering phytoplankton blooms that fueled krill swarms, seabirds, seals, and whales.

-

Autumn–Winter: Sea ice re-formed; most species migrated northward or entered dormancy.

From microbial mats in the Vestfold Hills to krill shoals spanning hundreds of kilometers, life followed a rhythm synchronized with light and ice — an enduring cycle of abundance and dormancy that predated human awareness by millennia.

Human Absence & Conceptual Geography

Antarctica lay completely outside the cognitive map of the Bronze and Iron Age world.

Even the most adventurous maritime cultures of the Indian and Pacific Oceans — Austronesians, Phoenicians, Egyptians, or South Americans — never neared these latitudes.

To ancient cosmologies, the far south was an unimaginable void, a theoretical counterbalance to known lands rather than a physical place.

Antarctica’s only history in this epoch was ecological, not human.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

The resilience of this polar system rested on feedbacks unique to ice-covered worlds:

-

Glacial advance and retreat periodically reconfigured coasts, creating new nesting terraces.

-

Ashfall from Antarctic and subantarctic volcanoes refreshed soils with minerals.

-

Peat and moss beds stabilized microclimates in rare oases.

-

Marine upwelling and krill flexibility ensured food web continuity through climatic oscillations.

Every storm, eruption, and freeze–thaw cycle renewed rather than destroyed the ecological fabric.

Transition

By 910 BCE, the Antarctic realm stood in late-Holocene equilibrium:

-

The East Antarctic Ice Sheet dominated the continent;

-

Subantarctic islands thrived with bird and seal colonies;

-

West Antarctic shelves hosted rich summer ecosystems;

-

And humanity remained utterly absent.

Antarctica entered the first millennium BCE as a closed world of ice and life, sustaining the planet’s southern oceanic engine — a realm of perpetual cold, unmarked by any human hand, yet central to Earth’s climate and biological stability.

Eastern East Antarctica (2637 – 910 BCE): The Polar Plateau’s Eastern Expanse

Geographic and Environmental Context

Eastern East Antarctica—stretching from the Ross Sea sector eastward past the Amery Ice Shelf toward the Australian Antarctic Territory—is dominated by the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, the largest ice mass on Earth. Its interior stands over 3,000 meters above sea level, buried beneath up to four kilometers of ice. Vast ice domes and ridges slope toward sheer coastal ice cliffs, floating ice shelves, and occasional rocky nunataks protruding above the ice. The region’s climate is hyper-polar, with annual mean temperatures well below freezing and some of the lowest precipitation levels on Earth, classifying it as a polar desert.

Climate and Seasonal Rhythms

-

Winter: Continuous darkness, extreme cold below –60°C, and katabatic winds draining off the ice sheet toward the coast.

-

Summer: Constant daylight along the coast, but interior temperatures remain far below freezing. Seasonal melting occurs only on the most exposed coastal rock and ice-free oases.

-

Precipitation: Minimal, falling almost entirely as snow, with accumulation rates in the interior measured in millimeters of water equivalent per year.

Biological Productivity

Life was almost entirely restricted to coastal and offshore zones in summer:

-

Adélie penguins and early forms of Emperor penguins bred on rocky beaches and stable sea ice.

-

Seals—including Weddell and leopard seals—hauled out on ice edges to rest and breed.

-

Seasonal phytoplankton blooms in ice-edge waters supported krill swarms, which in turn fed penguins, seabirds, and whales.

The ice-free Vestfold Hills and other rare coastal oases hosted microbial mats, lichens, mosses, and invertebrates like springtails and mites.

Human Presence

In 2637 – 910 BCE, Eastern East Antarctica was entirely beyond the reach of human settlement or exploration. The vast distances from inhabited lands, constant ice cover, and extreme climatic conditions made survival impossible with contemporary technology. Even indirect contact—via drift voyages—was effectively ruled out by surrounding pack ice and the absence of navigational knowledge of such latitudes.

Environmental Dynamics

-

Ice movement: Massive glaciers flowed toward the coast, feeding floating ice shelves such as the Amery and Shackleton.

-

Volcanism: Dormant and active subglacial volcanoes influenced local ice melting patterns.

-

Wind systems: Persistent katabatic winds shaped snow dunes and redistributed surface snow across the plateau.

Symbolic and Conceptual Role

For ancient peoples, this region was unimagined space—a blank zone south of the Southern Ocean, unseen and outside the realm of cultural geography. No myths or traditions from this period suggest knowledge of land far to the south.

Transition to the Early First Millennium BCE

By 910 BCE, Eastern East Antarctica remained one of the most isolated and least hospitable environments on Earth—an untouched realm of ice, wind, and sea life concentrated along its seasonal coastal edge. It would remain unseen by humans for many thousands of years.

Antarctica (909 BCE – 819 CE): Polar Plateaus, Icebound Mountains, and Oceanic Exchange

Regional Overview

During the first millennium BCE through the early first millennium CE, Antarctica remained a world apart—an immense, uninhabited ice continent influencing global climate but invisible to human experience.

Its glacial mass, atmospheric circulation, and surrounding seas shaped the rhythms of the Southern Hemisphere.

While civilizations across Afro-Eurasia mastered iron and empire, Antarctica’s silence was anything but static: the ice sheets advanced and withdrew in slow pulses, driving oceanic productivity and long-range climatic feedbacks that reached far beyond the polar horizon.

Geography and Environment

The Antarctic realm comprises two great continental divisions:

-

West Antarctica, a patchwork of mountain ranges, volcanic plateaus, and broad ice shelves stretching from the Antarctic Peninsula to Marie Byrd Land.

-

East Antarctica, the vast polar plateau rising more than 3 km above sea level, capped by the thickest ice on Earth.

Between them lies the Transantarctic Mountains, dividing basins that feed the Ross and Ronne–Filchner Ice Shelves.

Coastal oases—dry valleys, nunataks, and basalt ridges—supported microbial mats, lichens, and mosses, while the Southern Ocean teemed with life beneath a canopy of shifting ice.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The epoch fell within the late Holocene climatic envelope, cooler than mid-Holocene warmth yet far from glacial extremes.

Seasonal oscillations in the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) and polar vortex regulated sea-ice extent: winter expansion sealed the continent in darkness; summer retreats opened productive polynyas and continental-shelf habitats.

Ice cores later reveal slight shifts in snowfall and atmospheric composition—early signals of the interlinked hemispheric climate system already in operation.

Ecology and Life Systems

Antarctica’s continental interior supported only extremophile micro-ecosystems—bacteria, algae, and lichens adapted to freeze-thaw cycles and desiccation.

The surrounding Southern Ocean, by contrast, pulsed with abundance:

-

Krill blooms under melting sea ice sustained penguins, seals, and whales.

-

Adélie and gentoo penguins nested on ice-free rock ledges along the Antarctic Peninsula and South Shetland Islands.

-

Seals (Weddell, leopard, crabeater) bred on seasonal ice.

-

Seabirds—petrels, skuas, albatrosses—connected Antarctica to the sub-Antarctic island arcs.

This closed yet dynamic biosphere functioned as a planetary nutrient engine, cycling carbon and sustaining global marine food webs.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

The Southern Ocean was Antarctica’s true frontier.

The ACC circled the continent uninterrupted, coupling the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific basins.

Migrating whales, seals, and seabirds traversed these currents each austral summer, linking polar feeding grounds with subtropical calving or nesting zones.

Glacial melt streams and katabatic winds influenced sea-ice formation, subtly modulating global ocean circulation long before any human measurement could record it.

Cultural and Symbolic Dimensions

No people reached Antarctica in this age.

Yet the idea of a southern land—the terra australis incognita of later classical geography—may have originated in ancient attempts to balance the world map, an intuitive recognition that Earth’s symmetry required a polar counterweight.

In this sense, even without witnesses, the continent occupied a mythic position in the emerging human imagination: an unseen pole anchoring the planet’s equilibrium.

Adaptation and Resilience

Life persisted through ecological specialization.

Marine species synchronized breeding with sea-ice cycles; penguins adjusted colony sites to glacial advance or retreat.

Microbial communities entered dormancy during deep freezes and revived with meltwater pulses.

The ice sheet itself acted as both barrier and buffer, recording atmospheric history in its layers while regulating Earth’s albedo and sea level.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 819 CE, Antarctica remained an untouched continent—its glaciers untrammeled, its ecosystems self-regulated, its climatic influence planetary.

Together with the sub-Antarctic arcs of the Southern Indian and South Atlantic Oceans, it completed the Southern Ocean system that governed global circulation.

In its silence and endurance lay the prehuman foundation of the Earth’s climate engine: a frozen mirror reflecting the sky, a realm of continuity beneath iron-age stars.