West Polynesia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 144 total

West Polynesia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Paleolithic I — Volcanic High Islands, Atoll Seeds, and Reef-Edge Biota

Geographic & Environmental Context

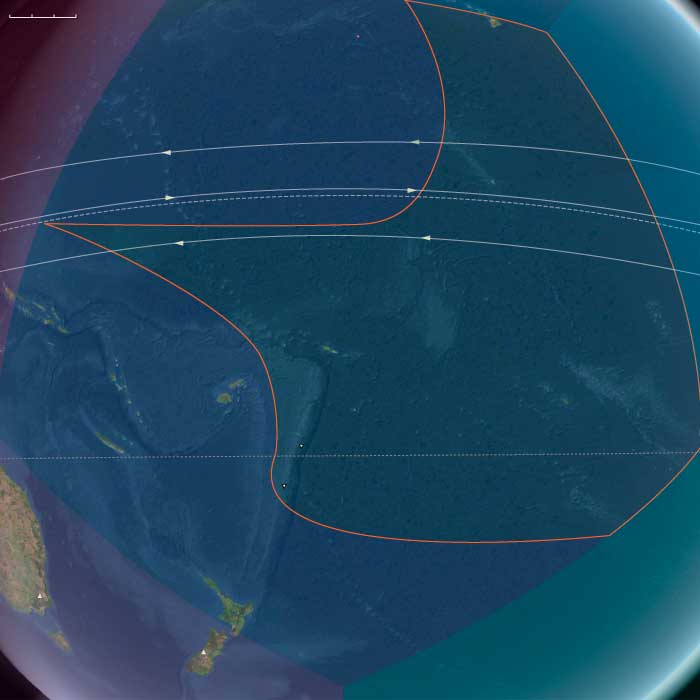

West Polynesia includes Hawaiʻi Island (the Big Island); Tonga (Tongatapu, Haʻapai, Vavaʻu); Samoa (Savaiʻi, Upolu, Tutuila/Manuʻa); Tuvalu and Tokelau (low atolls); the Cook Islands (Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Mangaia, etc.); Society Islands (Raiatea–Tahiti–Moʻorea–Bora Bora); and the Marquesas (Nuku Hiva, Hiva Oa).

-

Hawaiʻi Island still in an active shield-building phase (Mauna Loa, Mauna Kea); Societies, Marquesas, Cooks are high volcanic islands; Tuvalu–Tokelau are emergent low reef structures and paleo-atolls; Tonga–Samoa high islands/raised limestones.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Glacial world: sea level ~100 m lower; wide reef flats and drowned shelves exposed terraces and benches. Trades strong; cooler SSTs.

Biota & Baseline (No Human Presence)

-

Seabird supercolonies, turtle rookeries, monk seals (in NW line) on outer cays; uplands carry cloud/montane forests, leeward slopes dry woodland.

-

Reef accretion proceeds episodically; lagoons are shallower and more extensive than today.

Long-Term Significance

A geomorphic blueprint forms: high islands with fertile amphitheaters and burgeoning barrier reefs—future foundations for intensive ridge-to-reef food systems.

Polynesia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Paleolithic I — Volcanic Arcs, Reef Foundations, and the Architecture of Isolation

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the later Pleistocene, the Polynesian sector of the Pacific was a scattered domain of volcanic peaks, emerging atolls, and widening reef flats—a geography still entirely devoid of humans but already constructing the natural architecture that would one day sustain them.

The region spanned three great arcs of islands:

-

The Hawaiian–Emperor chain in the north, including Oʻahu, Maui, Molokaʻi, Kauaʻi, Niʻihau, and Midway, where high volcanic forms dominated the subtropics.

-

The central–western archipelagos—Tonga, Samoa, the Cook and Society Islands, the Marquesas, Tuvalu, and Tokelau—a mixture of high volcanic islands, raised limestone platforms, and embryonic atolls.

-

The eastern fringe—future Pitcairn and Rapa Nui—where lone volcanic edifices rose from deep ocean basins, linked only by the great South Pacific gyres and currents.

Sea level stood ~100 m lower than today, exposing vast coastal benches and broad shelves around high islands. Many modern lagoons lay dry, their reef rims fossilized in the air; others built episodically with interglacial warm phases. Across the region, reef, volcano, and ocean interacted in long cycles of uplift and subsidence—the slow choreography that would, over tens of millennia, produce the Polynesian Triangle’s intricate geography.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The epoch was framed by full glacial conditions—cooler sea-surface temperatures, stronger trade winds, and a sharply defined dry season.

-

Atmosphere and Ocean: Strengthened trades drove upwelling along many leeward coasts, favoring cool, nutrient-rich nearshore waters. Seasonal dust episodes and winter surf reworked coastal benches, while the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) oscillated northward and southward with orbital rhythms.

-

Late-Glacial Variability: Even within the long glacial, brief mild interstadials brought short-lived reef growth spurts and pulses of vegetation recovery. Cooler phases depressed the coral-algal community but expanded coastal steppe and dry scrub.

-

Volcanic Activity: Continuous effusive volcanism in the Hawaiian Big Island and intermittent eruptions in the Societies, Marquesas, and Cooks rejuvenated landscapes, built fresh lava plains, and created ephemeral crater lakes and ash-fed soils.

Overall, Polynesia’s climate oscillated between cool, windy glacial stability and short warming pulses that allowed the reef crest and forest line to advance and retreat in rhythm with the global climate.

Biota & Baseline Ecology (No Human Presence)

Every island was its own closed laboratory of evolution.

-

Marine Life:

Coral communities fluctuated with sea level and temperature, but even under glacial suppression, shallow fringing reefs persisted. Fish, mollusk, turtle, and seabird populations were immense, their only predators sharks and seals. On outer banks like Midway, Tokelau, and Tuvalu, monk seals and turtles bred in numbers far exceeding modern densities. -

Terrestrial Life:

The higher islands—Hawaiʻi, Tahiti, Samoa, the Marquesas—carried dense montane forests in windward belts and dry woodland or grass steppe on leeward slopes. Cloud forests crowned the summits, capturing mist even under glacial dryness. Each island hosted unique, isolated assemblages of birds, insects, and plants, evolving in splendid isolation. -

Avian Realms:

Seabird supercolonies occupied cliffs and stacks, fertilizing soils with guano and enriching nearshore ecosystems. On atolls and cays, the air was dense with terns, boobies, and petrels—an avian kingdom uninterrupted by human disturbance.

Environmental Processes & Dynamics

-

Reef and Lagoon Evolution: Lower sea levels exposed broad reef flats, which weathered into limestone benches; with each brief warming, corals recolonized and built new terraces—a staircase of future lagoons.

-

Volcano–Erosion Cycles: Heavy rainfall on high islands carved deep amphitheaters (e.g., Waiʻanae, Koʻolau, and Tahiti’s ancient calderas), while aridity on leeward slopes preserved lava plains and dunes.

-

Marine Productivity: Upwelling zones around island chains created feeding grounds for pelagic fish and whales; kelp-like macroalgae likely formed dense nearshore beds in cooler zones, anchoring early “reef forest” ecologies.

-

Atmospheric Circulation: Persistent trades sculpted the cloud belts that would later define Polynesian ecological duality—lush windward valleys and dry leeward coasts.

Long-Term Significance

By 28,578 BCE, Polynesia’s physical and biological foundations were firmly in place:

-

Volcanic arcs had matured into high-island chains with deep, fertile amphitheaters and developing river networks.

-

Coral reef systems, though suppressed by glacial cooling, had established their long-term frameworks, ready to surge during Holocene sea-level rise.

-

Forest and reef ecologies had stabilized into enduring zonations—ridge forests, dry scrub, coastal strand, reef-flat, and pelagic edge—that would persist through the Holocene.

The epoch thus created Polynesia’s essential blueprint: a world of towering volcanic islands, expanding reef terraces, seabird-sustained fertility, and unbroken ecological isolation.

In the ages to come, these formations would become the living stage for one of Earth’s greatest human voyaging traditions—a future civilization built upon the deep-time architecture of glacial Polynesia.

Polynesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene Transition — Emerging Arcs, Drowned Plateaus, and Reef Foundations

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, Polynesia—stretching from the Hawaiian archipelago across Samoa, Tonga, the Cook and Society Islands, to the far eastern outliers of Pitcairn and Rapa Nui—remained entirely unpeopled, a scattered constellation of volcanic and reefed islands rising above the world’s largest ocean.

At the Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500–19,000 BCE), global sea levels stood more than 100 m lower than today, exposing wide coastal shelves and tightening inter-island channels. As ice sheets melted, deglaciation flooded ancient shorelines, transforming basins into lagoons and seamounts into isolated atolls.

-

North Polynesia (Oʻahu, Maui Nui, Kauaʻi–Niʻihau, Midway Atoll): the Maui Nui shelf—once a single island—became a cluster of channels; Midway’s rim expanded as new lagoons formed.

-

West Polynesia (Hawaiʻi Island, Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu–Tokelau, Cook, Society, and Marquesas): reefs and barrier lagoons built up around volcanic peaks, while low atolls appeared as sea level rose.

-

East Polynesia (Pitcairn, Rapa Nui, and nearby seamounts): the farthest outposts of the Pacific, geologically young and ecologically self-contained, fringed by narrow reef flats and rich upwelling zones.

Across this immense realm, oceanic currents—the South and North Equatorial and the Kuroshio–Equatorial Counter-flow system—created predictable gyres, establishing the hydrological backbone that would later sustain Polynesian voyaging.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The epoch was one of oscillation and renewal:

-

Last Glacial Maximum (26,500–19,000 BCE): cooler seas and exposed shelves expanded coastal plains; coral growth slowed under lowered sea level.

-

Bølling–Allerød interstadial (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE): warmth and rainfall increased; reefs surged upward in “catch-up” growth; lagoons and barrier formations matured.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 BCE): brief cooling flattened reef accretion and restricted mangroves; trade-wind aridity spread in leeward belts.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): steady warming and sea-level stabilization allowed coral terraces, mangroves, and strand forests to reach near-modern equilibrium.

By 7822 BCE, the Pacific climate engine had achieved its Holocene rhythm—warm, humid, and oceanically stable.

Biota & Baseline Ecology (No Human Presence)

Polynesia’s ecosystems reached pristine balance under rising seas:

-

Reefs and lagoons flourished with coral, mollusks, crustaceans, and reef fish (parrotfish, surgeonfish, mullet); spur-and-groove structures and back-reef ponds became marine nurseries.

-

Coastal vegetation—pandanus, beach heliotrope, ironwood, and grasses—rooted in guano-enriched sands; strand forests stabilized dunes.

-

Cloud-forests cloaked high islands such as Tahiti and Savaiʻi, while dry leeward slopes supported shrub and palm mosaics.

-

Seabirds nested in immense colonies; turtles hauled out on beaches; marine mammals frequented newly formed bays.

All existed in predator-free isolation, each island a laboratory of speciation and resilience.

Geomorphic & Oceanic Processes

As the sea rose, island landscapes underwent continuous re-sculpting:

-

Reef accretion kept pace with transgression, forming the first true atoll rings.

-

Maui Nui’s plateau fragmented into separate islands; Hawaiʻi Island’s volcanic plains met new coasts.

-

Eastern high islands (Rapa Nui, Pitcairn) gained fertile volcanic soils through slow weathering; storm surges and wave reworking created terraces and embayments.

-

Sediment deltas at stream mouths formed early estuarine wetlands—future sites for Polynesian fishponds and irrigated terraces.

Symbolic & Conceptual Role

For millennia these lands remained beyond the human horizon—unimagined yet forming the ecological architecture that would one day welcome voyagers. Their mountains, lagoons, and reefs became the stage on which later Polynesian societies would enact origin stories of sea and sky.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Natural resilience was inherent:

-

Coral reefs tracked rising seas through vertical growth, preventing ecological collapse.

-

Guano-fertilized soils accelerated vegetative colonization after storm disturbance.

-

Cloud-forest hydrology maintained water flow even in drier pulses.

These feedbacks produced long-term equilibrium between land, sea, and atmosphere—the defining ecological rhythm of Polynesia.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Polynesia had become a fully modern oceanic system: drowned plateaus transformed into lagoons and atolls; coral terraces and forest belts stabilized; seabird and reef ecologies reached peak diversity.

Though still empty of humankind, the region now possessed every element—predictable currents, fertile reefs, sheltered bays, and stable climates—that would, tens of millennia later, make it the natural cradle of the world’s greatest voyaging tradition.

West Polynesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Paleolithic II — Deglaciation, Rising Seas, and Lagoon Maturation

Geographic & Environmental Context

West Polynesia includes Hawaiʻi Island (the Big Island); Tonga (Tongatapu, Haʻapai, Vavaʻu); Samoa (Savaiʻi, Upolu, Tutuila/Manuʻa); Tuvalu and Tokelau (low atolls); the Cook Islands (Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Mangaia, etc.); Society Islands (Raiatea–Tahiti–Moʻorea–Bora Bora); and the Marquesas (Nuku Hiva, Hiva Oa).

-

Anchors: Mauna Loa–Mauna Kea lava fields; Tongatapu–Haʻapai fringing lagoons; Rarotonga–Aitutaki reef flats; Raiatea–Tahiti leeward lagoons; Nuku Hiva embayments; Tuvalu–Tokelau reef rims.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Deglaciation drives rapid sea-level rise; coastlines retreat landward; coral growth keeps pace, building spur-and-groove and back-reef ponds.

-

Bølling–Allerød warm spike then Younger Dryas cool snap; Early Holocene warmth stabilizes.

Biota & Baseline (No Human Presence)

-

Lagoons teem with mullet, surgeonfish, parrotfish; strand-forest and dune systems expand; montane cloud forests intact.

Long-Term Significance

Creation of stable lagoons and wetland back-beach ponds—ideal future sites for loko iʻa (fishponds) and irrigated terraces.

Central Oceania, the twelfth of the Earth’s regions centered on the South Pacific Ocean, encompasses the Hawaiian Islands, New Zealand’s North Island, and the archipelagos of Western Polynesia, Eastern Melanesia, and Eastern Micronesia. This includes groups such as French Polynesia, Tonga, Niue, the Cook Islands, Fiji, Tokelau, Vanuatu, the eastern Solomon Islands, Nauru, Tuvalu, Samoa, and the Marshall Islands.

Its northwestern boundary separates the Solomon Islands from the easternmost islands of Papua New Guinea, including Bougainville, Buka, and several outlying islands and atolls historically known as the Northern Solomons.

The southeastern boundary divides West Polynesia, which includes the Big Island of Hawaii, from East Polynesia, represented by the Pitcairn Islands and Easter Island.

HistoryAtlas contains 399 entries for Central Oceania from the Paleolithic period to 1899.Narrow results by searching for a word or phrase or select from one or more of a dozen filters.

There is no evidence of human beings having lived in Oceania before about 31,000 BCE.

If they did, they would have lived along the coasts of the various small islands, and evidence would have long since disappeared below the rising seas of the Holocene Epoch.

A dramatic and rapid rise in global sea-levels of around fourteen meters is linked by coral off the South Pacific island of Tahiti to the collapse of massive ice sheets fourteen thousand six hundred years ago.

An Aix-Marseille University-led team, including Oxford University scientists Alex Thomas and Gideon Henderson, confirmed that a dramatic and rapid rise in global sea-levels of around fourteen meters occurred at the same time as a period of rapid climate change known as the Bølling oscillation.

The Bølling oscillation, a warm interstadial period between the Oldest Dryas and Older Dryas stadials, at the end of the last glacial period, is used to describe a period of time in relation to Pollen zone Ib—in regions where the Older Dryas is not detected in climatological evidence, the Bølling-Allerød is considered a single interstadial period.

The beginning of the Bølling is also the high-resolution date for the sharp temperature rise marking the end of the Oldest Dryas at 14,670 BP and the beginning of the so-called Humid Period in North Africa.

The region that will later become the Sahara is wet and fertile, its aquifers full.

During the Bølling warming high latitudes of the Northern hemisphere warmed as much as 15 degrees Celsius in a few tens of decades.

The team has used dating evidence from Tahitian corals to constrain the sea level rise to within a period of three hundred and fifty years, although the actual rise may well have occurred much more quickly and would have been distributed unevenly around the world's shorelines.

A leading theory is that the ocean's circulation changed so that more heat was transported into Northern latitudes.

A considerable portion of the water causing the sea-level rise at this time must have come from melting of the ice sheets in Antarctica, which sent a 'pulse' of freshwater around the globe.

However, whether the freshwater pulse helped to warm the climate or was a result of an already warming world remains unclear.

West Polynesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Cloud-Forest Belts and Productive Reef–Valley Coupling

Geographic & Environmental Context

West Polynesia includes Hawaiʻi Island (the Big Island); Tonga (Tongatapu, Haʻapai, Vavaʻu); Samoa (Savaiʻi, Upolu, Tutuila/Manuʻa); Tuvalu and Tokelau (low atolls); the Cook Islands (Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Mangaia, etc.); Society Islands (Raiatea–Tahiti–Moʻorea–Bora Bora); and the Marquesas (Nuku Hiva, Hiva Oa).

-

Anchors: Hawaiʻi Island windward ravines; Savaiʻi–Upolu perennial streams; Tongatapu–Haʻapai shelf lagoons; Raiatea–Tahiti deep valleys; Rarotonga–Mangaia alluvial fans; Nuku Hiva–Hiva Oa amphitheaters; Tuvalu–Tokelau atoll flats.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Thermal optimum: predictable trades, strong orographic rain on windward slopes, moderate ENSO.

Biota & Baseline (No Human Presence)

-

Endemic montane and mesic forests at peak; valley floors carry wetlands; reef productivity high; seabird guano subsidizes nutrient cycling on islets.

Long-Term Significance

An integrated ridge–stream–reef continuum matures across all high islands.

Polynesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Thermal Optimum Seas and Islands in Equilibrium

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Early Holocene, Polynesia—extending from the Hawaiian archipelago across Samoa, Tonga, and the Society Islands to the still-forming volcanic ridges of what would become Rapa Nui and Pitcairn—remained entirely unpeopled yet ecologically self-organized.

The global thermal optimum (c. 8,000–6,000 BCE) raised sea-surface temperatures and stabilized wind and current systems across the tropical Pacific.

High islands such as Oʻahu, Tahiti, and Savaiʻi bore deep belts of cloud forest, while their leeward coasts supported expanding reef-lagoon mosaics.

Emergent atolls and carbonate platforms—Tuvalu, Tokelau, and Midway—stood as low, gleaming rims on a still-rising ocean, already threaded by trade-wind-driven nutrient circuits.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Early Holocene Optimum produced the warmest and most stable Pacific climate of the Quaternary.

-

Sea levels continued their post-glacial rise, reaching only a few meters below present; newly drowned coastal shelves became lagoons and barrier-reef arcs.

-

Trade winds and monsoonal convergence zones settled into predictable rhythms, ensuring orographic rain on windward mountains and long dry seasons on leeward coasts.

-

ENSO activity was weak or absent; the Pacific climate engine ran with near-mechanical reliability.

These steady conditions allowed ecosystems to mature without major disturbance for more than a millennium.

Biota & Baseline Ecology (Before Human Arrival)

Polynesia at this stage was a realm of maximal endemic richness and ridge-to-reef productivity:

-

Forests: dense montane and mesic stands of hardwoods, Pandanus, and tree ferns cloaked volcanic slopes; lowlands carried palm and coastal scrub communities.

-

Freshwater systems: perennial streams sculpted alluvial fans and fed wetland complexes behind beach ridges—later to become ideal taro-pond basins.

-

Reefs and lagoons: coral growth kept pace with sea-level rise; fish biomass, clam beds, and crustacean diversity peaked; guano from seabird colonies fertilized nearshore flats.

-

Seabird rookeries blanketed outer islets, coupling marine nitrogen to terrestrial fertility.

-

Atolls and low islands: thin soils supported grasses, heliotropes, and mangrove thickets along brackish lagoons—incipient blueprints for future habitation.

Geomorphic and Oceanic Processes

A gentle post-glacial transgression reshaped Polynesia’s coastlines: drowned river mouths became estuaries and bay-head deltas; reef crests migrated upward; mangroves and peat lenses accumulated behind storm ridges.

Volcanic islands such as Hawaiʻi Island, Tahiti, and Rarotonga continued to build and erode simultaneously, feeding rich sediment to deltas.

Across the central Pacific, the South Equatorial Current and its counterflows organized enduring biological highways, prefiguring the navigation corridors of future voyagers.

Regional Profiles

-

North Polynesia (Hawaiian chain except Hawaiʻi Island): Warm seas and reliable trades sustained lush cloud-forest belts, valley wetlands, and stable lagoon fisheries.

-

West Polynesia (Hawaiʻi Island, Samoa, Tonga, Society Islands, Cook Islands, Tuvalu–Tokelau, Marquesas): Reef–valley coupling reached perfection—mountain rainfall feeding coastal productivity.

-

East Polynesia (Pitcairn group, Rapa Nui, and outlying ridges): Newly emergent volcanic highlands and surrounding seamounts hosted pioneer flora—ferns, grasses, and mosses—and rapidly accreting coral rims.

Together these arcs formed a climatic and ecological continuum, unbroken by storm or current.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Without humans, natural feedback loops maintained equilibrium:

-

Cloud-forest evapotranspiration recycled rainfall; mangroves trapped sediment and built new ground.

-

Coral reefs tracked sea-level rise through vertical accretion, preserving lagoon depth and productivity.

-

Seabirds, turtles, and migratory fish redistributed nutrients across thousands of kilometers.

Disturbance—occasional cyclone or lava flow—was localized and quickly absorbed, strengthening rather than destabilizing ecosystem complexity.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Polynesia had reached its pre-human ecological zenith.

Across every island chain, the ridge-to-reef continuum—from cloud forest to stream to reef flat—operated in perfect balance.

These conditions provided the environmental templates for later Polynesian agriculture, aquaculture, and navigation.

The Early Holocene thus marked an age of formation rather than transformation—a prolonged prelude in which the ocean composed its stage for the human voyaging worlds to come.

There is no evidence of settlement in the islands of Oceania during the Neolithic period; it will not be until around three thousand years before the present that the ancestors of the Melanesian and Polynesian peoples will arrive to settle the many tiny, far-flung islands of this vast watery region.