East Micronesia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 45 total

Micronesia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Submerged Ridges, Atoll Seeds, and the Empty Reefs of a Cooler Pacific

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the later Pleistocene, Micronesia stretched across a vast mid-Pacific sweep of volcanic highs, raised limestone plateaus, and nascent atoll rims poised atop the Pacific Plate. The region was already divided into its two enduring structural arcs:

-

West Micronesia: the Mariana Islands (Guam, Saipan, Tinian, Rota, and the northern seamount chain), Palau(Babeldaob, Koror, Rock Islands), and Yap with its surrounding low atolls (Ulithi–Woleai arc).

These islands formed along ancient volcanic and tectonic arcs rising from deep basins—rugged highlands and carbonate terraces that stood above a narrow shelf. -

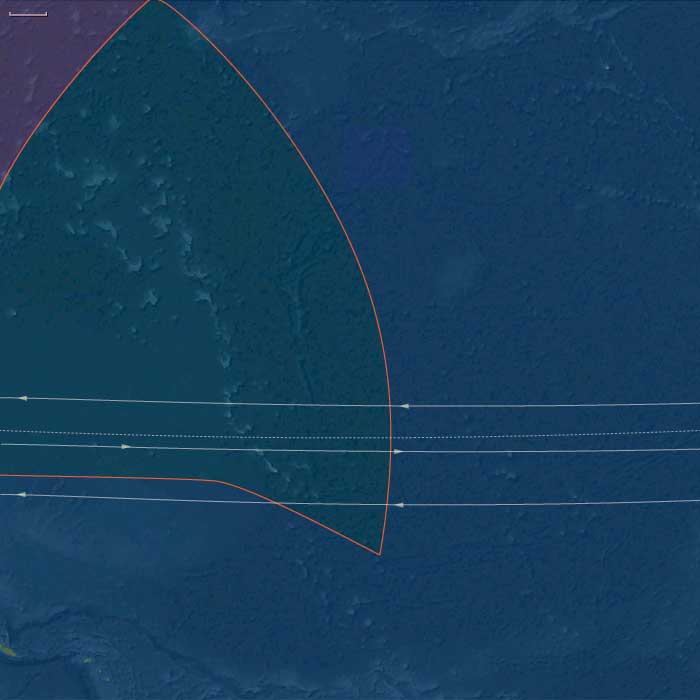

East Micronesia: the Marshall Islands (Ralik and Ratak chains), the Gilberts (Kiribati), Nauru, and the eastern Carolines (Kosrae)—a realm of reefed ridges, uplifted limestones, and isolated volcanic cones surrounded by wide lagoon systems.

At this time, sea level lay roughly 100 meters below modern, exposing reef flats and submerged coastal terraces across the entire Pacific basin. Many of today’s lagoons and passes existed only as broad intertidal plains or dry benches. The exposed reefs baked under strong trade winds and saline spray, while the high islands of Palau, Yap, and Kosrae maintained forested uplands and perennial streams under cooler, drier skies.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Late Pleistocene Pacific was a cooler, windier world, governed by strengthened trade winds and steeper thermal gradients between equator and subtropics:

-

Temperature & Ocean Circulation: Sea-surface temperatures dropped 2–3 °C below present. The west Pacific warm pool contracted eastward, reducing rainfall over central Micronesia.

-

Rainfall & Storms: Monsoon and intertropical convergence zones shifted northward; dry seasons lengthened, and cyclone frequency declined under a more stable, cooler ocean–atmosphere regime.

-

Sea Level & Geomorphology: Reef accretion slowed or paused; many atoll rims stood high and dry as limestone terraces. Submerged seamounts, ridges, and banks—future Ralik–Ratak, Palau–Yap, and Ulithi–Woleai chains—were transformed into low scrub islands or bare carbonate plains.

-

Volcanism: Kosrae, Palau, and the northern Marianas remained volcanically active, releasing ash that enriched soils and supported cloud forest pockets.

Biota & Baseline Ecology (No Human Presence)

Though entirely uninhabited, the Micronesian region supported vibrant marine and avian ecosystems, organized along windward–leeward contrasts and high–low island gradients.

-

Marine Systems:

• Coral diversity contracted but persisted on outer slopes below the lowered sea level.

• Exposed flats hosted intertidal mollusks, crabs, and urchins, while submerged reef slopes remained refuges for reef fish and sharks.

• Cooler waters and upwelling zones favored planktonic blooms around high islands and seamount edges, sustaining pelagic fish and turtles. -

Terrestrial & Avian Life:

• Seabird supercolonies dominated the low atolls and terraces—boobies, terns, frigatebirds, petrels—depositing guano that enriched emerging soils.

• Turtles nested on extensive beaches exposed by low sea stands.

• On volcanic high islands (Yap, Palau, Kosrae), montane forests of ferns, pandanus, and palms persisted, harboring endemic birds, fruit bats, and invertebrates.

• Nauru’s elevated plateau supported scrub adapted to aridity and phosphate-rich soils.

Environmental Processes & Dynamics

-

Reef Morphodynamics: Exposed reefs weathered and fractured; their margins became the foundation for the Holocene reef rims and lagoon systems that would later define Micronesian atolls.

-

Hydrological Cycles: Reduced rainfall limited freshwater lenses on low islands, while high islands retained groundwater-fed streams and crater lakes.

-

Wind and Sediment: Persistent trades reworked coral rubble into beach ridges and dunes—landforms that fossilized as Pleistocene terraces visible in many modern atolls.

-

Ocean Productivity: The combination of cooler waters and intensified upwelling sustained rich pelagic ecosystems around all major island arcs, even as shallow reefs lay dormant.

Symbolic & Conceptual Dimensions

No humans yet traversed this ocean. For tens of millennia, Micronesia existed only as a biological archipelago—reef to reef, wind to current—its atolls forming unseen scaffolds for the civilizations to come. Every island was a silent nursery: for coral larvae drifting on trade winds, for seabird colonies seeding future soils, for volcanic ridges waiting to host human voyagers millennia hence.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

The ecosystems of both western and eastern Micronesia demonstrated striking resilience:

-

Coral frameworks survived exposure and reemerged once seas rose.

-

Guano fertilization jump-started terrestrial soil development.

-

Volcanic renewal on Palau, Yap, and Kosrae maintained forest refugia during dry glacial phases.

-

Ocean circulation ensured continual nutrient renewal even during climatic downturns.

These processes collectively prepared Micronesia for the Holocene transgression, when reefs would again flourish and lagoons fill—a transformation that would give the region its modern face.

Long-Term Significance

By 28,578 BCE, Micronesia was already architecturally complete in geological terms:

-

Reef platforms, high-island watersheds, and carbonate terraces had all been established.

-

The region’s biological endemism and reef frameworks were in place, awaiting Holocene recolonization by corals, forests, and, eventually, humans.

-

Its position at the confluence of the equatorial currents and trade-wind belts had fixed the environmental patterns that would later shape Micronesian navigation, settlement, and subsistence.

In essence, the glacial Micronesian world was a prelude in stone and coral—the formation of the reefs, lagoons, and winds that would one day become the foundation of the Pacific’s smallest yet most interconnected oceanic realm.

East Micronesia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene — Reef Platforms, Windward Rims, and Seabird Realms (No Human Presence)

Geographic & Environmental Context

East Melanesia includes Kiribati (Gilbert Islands), the Marshall Islands (Ralik and Ratak chains), Nauru (uplifted phosphatic limestone island), and Kosrae (high, volcanic island on the eastern Caroline arc).

-

Sea level sat ~100 m below modern, exposing broad reef flats and terrace benches on the future Ralik–Ratak and Gilbert atolls; Nauru stood as a higher limestone mesa; Kosrae loomed as a steep volcanic high island with deep valleys.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Last Glacial Maximum: cooler SSTs, stronger trades and winter swell; slower coral accretion but wide intertidal zones.

Baseline Ecology

-

Seabird supercolonies nested on outer cays; turtles used broad beaches; lagoonal microhabitats were incipient.

-

Kosrae’s montane forest and unmodified streams sustained high freshwater biodiversity.

Long-Term Significance

These lowstand landscapes fixed the reef foundations and high-island watersheds that later support Micronesian arboriculture, taro pondfields, and lagoon fisheries.

East Micronesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Deglaciation — Drowning Shelves, Lagoon Formation, and Reef “Catch-Up” (No Human Presence)

Geographic & Environmental Context

East Melanesia includes Kiribati (Gilbert Islands), the Marshall Islands (Ralik and Ratak chains), Nauru (uplifted phosphatic limestone island), and Kosrae (high, volcanic island on the eastern Caroline arc).

-

Rapid sea-level rise flooded glacial benches, carving pass channels and back-reef lagoons across the Ralik–Ratak and Gilbert platforms; Nauru became a ringed limestone island; Kosrae gained new fringing reef flats.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød warmth boosted coral growth; Younger Dryas slowed it briefly; Early Holocene warmth stabilized reef accretion and lagoon development.

Baseline Ecology

-

Mature lagoons supported mullet, surgeonfish, parrotfish; outer reefs grew spur-and-groove structures.

-

Dune–strand forests stabilized cays; Kosrae’s wet windward slopes fed productive estuaries.

Long-Term Significance

The lagoon–reef architecture that later anchors fish weirs, clam gardens, and canoe passes took recognizable form in this era.

Micronesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Rising Seas, Reef Builders, and Islands Beyond Human Reach

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, Micronesia—spanning the Marianas, Palau, Yap, the Caroline arc, and the Gilberts and Marshalls—was a vast expanse of reefs and islands slowly emerging into their modern form.

At the Last Glacial Maximum (26,500–19,000 BCE), sea levels lay more than 100 m below present, enlarging volcanic islands and exposing broad limestone terraces across the Marianas and Yap. As global ice sheets melted, rising seas drowned coastal shelves, carved lagoon passes, and transformed former uplands into rings of atolls and reef-rimmed embayments.

By the end of this period, Micronesia’s archipelagic geometry—chains of high volcanic islands interlaced with low coral platforms—had taken shape, but it remained entirely beyond human knowledge or navigation.

-

West Micronesia: the Marianas, Palau, and Yap, a mix of volcanic high islands, raised limestone plateaus, and emerging atolls.

-

East Micronesia: the Gilberts (Kiribati), Marshalls (Ralik–Ratak), Nauru, and Kosrae, where low coral plains and volcanic headlands framed nascent lagoons.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Across these millennia, Micronesia oscillated between glacial austerity and interglacial abundance:

-

Last Glacial Maximum: cooler seas and weaker monsoons lowered rainfall and slowed coral accretion; broad coastal plains expanded on high islands.

-

Bølling–Allerød warming (14,700–12,900 BCE): warmer seas and renewed precipitation revived reefs and forests; lagoons deepened.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 BCE): a short cooling pulse reduced coral growth rates but had limited ecological disruption.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): warming stabilized, and coral “catch-up” growth filled drowned basins with vibrant reef life.

By 7,800 BCE, the modern climatic regime of steady trades, wet monsoons, and stable sea temperatures was established.

Flora, Fauna, and Baseline Ecology

Without human disturbance, Micronesia’s ecosystems thrived in pristine isolation:

-

High islands (Marianas, Palau, Kosrae) supported dense tropical rainforests—palms, hardwoods, tree ferns, and lianas—enclosing fertile volcanic soils.

-

Low coral islands (Marshalls, Gilberts, Yap outer arc) bore salt-tolerant scrub, pandanus, and grasses stabilized by guano-enriched sands.

-

Lagoons and reefs teemed with parrotfish, surgeonfish, mullet, turtles, and reef invertebrates; seabird colonies nested on rocky headlands.

-

Nauru’s uplifted limestone retained small freshwater pockets sustaining hardy shrubs and seabird rookeries.

-

Estuaries of Kosrae and Palau formed wetlands fed by volcanic runoff—hubs of biodiversity that would one day support human wet-field cultivation.

Geomorphic and Oceanic Dynamics

The transformation from continental shelves to island reefs defined Micronesia’s emergence:

-

Rapid deglacial sea-level rise flooded glacial terraces, producing lagoonal amphitheaters and pass channelsstill visible today in the Marshalls and Gilberts.

-

Reefs “caught up” to the rising sea, accreting vertically to preserve light access.

-

Volcanic activity in the Marianas arc renewed soils and reshaped coasts.

-

Cyclones and monsoon floods reworked beaches, continually redistributing sediments and forming the foundations of future atoll chains.

Through these processes, Micronesia’s reef–lagoon–islet system reached near-modern configuration long before any human sails appeared on the horizon.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

No human networks yet crossed this oceanic space.

Instead, natural circulations dominated:

-

The North Equatorial Current and its Countercurrent sculpted nutrient flows across the Caroline arc.

-

Migratory seabirds and turtles traced seasonal loops from the Philippines and Melanesia to Micronesian rookeries.

-

Driftwood, seeds, and pumice arrived via the Kuroshio and equatorial gyres, seeding plant life on newly formed cays.

In this epoch, wind and wave were the only navigators, the ocean itself the sole agent of exchange.

Symbolic and Conceptual Role

To late Pleistocene humans living along the western Pacific rim, Micronesia lay entirely beyond the conceivable horizon—neither seen nor imagined.

These island chains, thousands of kilometers from the nearest continental coast, existed only as natural monuments to isolation—the unvisited heart of the Pacific that would, much later, become the ocean’s crossroads.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Ecosystems displayed profound resilience:

-

Coral growth kept pace with rapid sea-level rise, preventing reef drowning.

-

Vegetation succession—first grasses and herbs, then palms and forests—stabilized soils and buffered erosion.

-

Seabird and turtle migrations maintained nutrient loops between ocean and land.

-

Lagoon sediments trapped organics, forming the fertile substrates that would one day support human gardening and settlement.

Micronesia emerged from deglaciation as a self-renewing biological network, balanced between storm energy and coral productivity.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Micronesia had reached ecological maturity.

Its reefs, lagoons, and volcanic highlands had stabilized into recognizable modern systems, with thriving biota and complex nutrient webs.

No humans yet crossed these waters, but the oceanic geography—chains of atolls spaced within sightlines, reefs protecting calm lagoons, dependable currents and winds—was complete.

The stage was set for the future age of voyagers: when humans finally arrived millennia later, they would find a world already perfectly tuned to sustain maritime civilization.

Central Oceania, the twelfth of the Earth’s regions centered on the South Pacific Ocean, encompasses the Hawaiian Islands, New Zealand’s North Island, and the archipelagos of Western Polynesia, Eastern Melanesia, and Eastern Micronesia. This includes groups such as French Polynesia, Tonga, Niue, the Cook Islands, Fiji, Tokelau, Vanuatu, the eastern Solomon Islands, Nauru, Tuvalu, Samoa, and the Marshall Islands.

Its northwestern boundary separates the Solomon Islands from the easternmost islands of Papua New Guinea, including Bougainville, Buka, and several outlying islands and atolls historically known as the Northern Solomons.

The southeastern boundary divides West Polynesia, which includes the Big Island of Hawaii, from East Polynesia, represented by the Pitcairn Islands and Easter Island.

HistoryAtlas contains 399 entries for Central Oceania from the Paleolithic period to 1899.Narrow results by searching for a word or phrase or select from one or more of a dozen filters.

There is no evidence of human beings having lived in Oceania before about 31,000 BCE.

If they did, they would have lived along the coasts of the various small islands, and evidence would have long since disappeared below the rising seas of the Holocene Epoch.

Micronesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Reef Stability, Freshwater Lenses, and Islands in Formation

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Early Holocene, Micronesia—a vast constellation of atolls, raised limestone islands, and volcanic high islands—was still settling into its modern geography.

Rising postglacial seas transformed once-emergent platforms into lagoons, reef arcs, and perched freshwater systems.

Two principal environmental spheres defined the region:

-

West Micronesia, including the Marianas, Palau, and Yap groups, where volcanic and limestone islands anchored extensive fringing reefs and early mangrove belts.

-

East Micronesia, encompassing the Gilberts, Marshalls, Nauru, and Kosrae, where reef–lagoon systems matured into stable atoll chains and freshwater lenses developed beneath them.

This was a time before human arrival, when wind, coral, and rainfall were the master engineers.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal optimum brought warmer sea-surface temperatures, steady trade winds, and reliable monsoon rainfall.

Sea level rose slowly toward its mid-Holocene highstand, submerging reef flats and stabilizing lagoon hydrology.

-

Atolls became fully enclosed systems with perched freshwater lenses, fed by rainfall infiltration and sealed by the porosity of coral sand.

-

High islands like Kosrae and Palau developed complex ridge-to-reef watersheds, with perennial streams delivering sediment and nutrients to lagoon nurseries.

Occasional storm events reworked coastal dunes, forming sabkha pockets and back-pond wetlands, but the broader climatic regime remained calm and predictable.

Baseline Ecology (Before Human Presence)

Micronesia’s ecological architecture reached a mature prehuman balance:

-

Atolls: newly consolidated lagoons teemed with coral, mollusks, and crustaceans. Lens-fed wetlands and brackish depressions behind ridges supported sedges, mangroves, and salt-tolerant grasses.

-

High islands (Palau, Kosrae): dense cloud forests and riparian corridors developed on volcanic slopes; rivers carved ravines that merged with reef-fringed estuaries.

-

Mangrove–reef coupling: decaying leaf litter and root detritus fertilized lagoon systems, feeding crabs, mollusks, and juvenile fish.

-

Seabirds nested along rocky headlands and outer islets, their guano linking ocean and land nutrient cycles.

These ecosystems functioned as closed hydrological loops—each island a miniature, self-regulating world.

Geomorphic and Hydrological Processes

As sea level stabilized, hydrology became the key ecological force:

-

Freshwater lenses, suspended above saltwater tables, expanded beneath coral islands, storing rainfall for future wells and taro pits.

-

Sediment accretion from storm reworking built natural ridges that enclosed lagoons.

-

Reef crests diversified into spur-and-groove systems, buffering waves and promoting lagoon calm.

-

Mangrove colonization anchored coastlines, consolidating organic soils and trapping fine sediments.

By 6,000 BCE, these systems had reached quasi-modern stability, setting the stage for eventual human adaptation to each hydrological niche.

Regional Profiles

-

West Micronesia (Marianas, Palau, Yap):

The Marianas’ limestone plateaus supported early lens wetlands, while Palau’s volcanic core and Rock Islands lagoon delivered sediment to mangroves and coral flats. Yap’s raised reef islands paired coastal marshes with outer atoll fisheries, creating natural templates for later garden–reef economies. -

East Micronesia (Gilberts, Marshalls, Nauru, Kosrae):

On the atolls, broad freshwater lenses and back-lagoon wetlands developed under steady rainfall. Nauru’s uplifted phosphate terrain held pockets of shallow groundwater. Kosrae, a high volcanic island on the eastern Caroline arc, became a hydrological hub, its clear perennial streams anticipating the wet-field taro cultivation of later millennia.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Without humans, ecosystems self-tuned through hydrological feedbacks:

-

Rainfall infiltration and coral permeability balanced freshwater and saltwater mixing.

-

Mangroves and beach vegetation stabilized ridges and protected lenses from salinity intrusion.

-

Coral accretion kept reef surfaces aligned with sea-level rise, preventing lagoon stagnation.

-

Guano enrichment enhanced terrestrial productivity, fertilizing sparse atoll soils.

These processes collectively forged the resilient ecological foundations that would later sustain Micronesian agriculture and navigation.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Micronesia had entered its Holocene ecological maturity.

Across thousands of kilometers of ocean, atolls and high islands had stabilized into enduring hydrological systems: freshwater lenses, mangrove belts, lagoon reefs, and volcanic watersheds.

These natural formations would become the infrastructure for future human settlement—the freshwater wells, taro pits, and canoe channels of later island cultures.

The Early Holocene was thus an age of silent preparation, when wind, wave, and coral sculpted the stage on which the later seafaring societies of Micronesia would thrive.

East Micronesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Freshwater Lens Growth and Reef–Valley Coupling (No Human Presence)

Geographic & Environmental Context

East Melanesia includes Kiribati (Gilbert Islands), the Marshall Islands (Ralik and Ratak chains), Nauru (uplifted phosphatic limestone island), and Kosrae (high, volcanic island on the eastern Caroline arc).

-

Anchors: broad, perched freshwater lenses began forming beneath Gilbert and Marshall atolls; Kosrae consolidated as a high-island hydrological hub.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Holocene thermal optimum: stable trades, warm SSTs, reliable rainfall; occasional Kona-like storm systems.

Baseline Ecology

-

Atolls: lens-fed wetlands and shallow sabkha pockets formed behind beach ridges; reef flats and passes matured.

-

Kosrae: dense cloud forests, uncut valleys, and intact riparian corridors.

Long-Term Significance

These freshwater lenses are the future substrate for sunken taro gardens (taro pits) and village wells; Kosrae’s perennial streams anticipate wet-field taro.

There is no evidence of settlement in the islands of Oceania during the Neolithic period; it will not be until around three thousand years before the present that the ancestors of the Melanesian and Polynesian peoples will arrive to settle the many tiny, far-flung islands of this vast watery region.

Micronesia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Reef Highstands and the Formation of Island Worlds

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Middle Holocene, Micronesia—a vast expanse of atolls, high volcanic islands, and raised limestone platforms scattered across the western and central Pacific—was shaped by rising seas and stabilizing reefs.

The region’s two great arcs—West Micronesia (Marianas, Palau, Yap and its outer atolls) and East Micronesia (Marshall Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, and Kosrae)—were joined by shared geomorphic and oceanic processes.

A global Hypsithermal highstand lifted sea levels slightly above modern, flooding reef flats and broadening lagoons.

-

In the Marianas and Yap–Palau corridor, limestone terraces and volcanic uplands framed newly expanded back-reef wetlands and sand spits.

-

In the Gilberts and Marshalls, atoll rims stabilized into continuous coral arcs enclosing calm inner lagoons.

-

On Nauru and Kosrae, interior depressions and river mouths developed freshwater and estuarine niches.

These transformations produced the modern outlines of reef, lagoon, and pass that would later sustain some of the world’s most sophisticated oceanic societies.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm phase brought warm, humid stability moderated by the vast Pacific’s thermal inertia.

ENSO oscillations existed but were weaker than in later millennia, bringing occasional dry intervals followed by abundant rains.

Cyclones struck episodically, reworking beaches and passes but rarely causing long-term change. The constancy of the trade-wind regime kept the region’s climate predictable, with gentle alternations between wet and dry seasons.

This steadiness allowed reefs to accrete vertically and horizontally, keeping pace with sea-level rise and forming complex lagoonal systems that approached their modern configuration.

Baseline Ecology (Before Human Arrival)

These were fully mature marine landscapes without human presence, yet biologically vibrant and self-regulating.

-

Atoll lagoons supported dense fish and invertebrate populations: parrotfish, wrasses, giant clams, and crabs filled reef crests and channels.

-

Mangrove and pandanus forests stabilized leeward rims and shore ridges, fixing sediments and nurturing brackish nurseries.

-

Kosrae’s rivers and estuaries hosted prawns, gobies, and mullet; Nauru’s karst hollows accumulated rainwater and supported freshwater crustaceans.

-

Seabirds and turtles nested in abundance, transferring marine nutrients ashore and fertilizing coastal vegetation.

-

Offshore, rich planktonic productivity sustained tuna and other pelagic species that later generations would harvest by sail and line.

Ecological succession had achieved ridge-to-reef balance—a complete, resilient system awaiting the first human voyagers.

Geomorphological Development

The mid-Holocene highstand sculpted Micronesia’s enduring geography.

Back-reef lagoons deepened and stabilized, sand cays coalesced into permanent islands, and mangroves colonized new shorelines.

Reef passes matured into stable tidal channels, establishing the hydraulic pattern that would later guide canoe passages, fish weirs, and anchorage basins.

In uplifted zones such as Guam and Yap, coastal terraces and shallow soils formed over ancient coral limestone, providing the first terrestrial frameworks for future agriculture.

This was the foundational moment when Micronesia’s ecological architecture—the template of its islands and reefs—became fixed.

Movement & Interaction Corridors (Natural, Not Human)

Though humans had not yet reached the region, ocean currents and migratory species created natural corridors of connection.

The North and South Equatorial Currents swept east–west across the atoll chains, redistributing coral larvae, seeds, and driftwood.

Seabird flyways and turtle migrations linked Micronesia with Melanesia and Polynesia, forming a living biological network that prefigured later maritime exchange routes.

These natural patterns of flow and renewal would become, millennia later, the “invisible maps” followed by Micronesian navigators tracing the same corridors by sail and star.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Micronesia’s ecosystems thrived through redundancy and regeneration.

Coral communities diversified with every disturbance, recolonizing storm-damaged zones within years. Mangroves advanced along sedimented inlets, protecting lagoon margins.

Seabirds shifted colonies as sand cays formed or eroded, maintaining species continuity across the archipelagos.

The equilibrium between oceanic productivity and terrestrial colonization produced one of the most resilient ecological systems on Earth, capable of self-repair across millennia of climatic fluctuation.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Micronesia stood as a fully realized oceanic ecosystem, its reefs, lagoons, and high islands sculpted into the forms still visible today.

Though uninhabited, the region’s landscapes—reef passes, atoll ponds, freshwater lenses, and mangrove-lined bays—had reached the precise configuration that would later support canoe navigation, aquaculture, and sustainable atoll agriculture.

The enduring lesson of this epoch is one of natural preparation: the sea and coral had already built the infrastructure of life, awaiting the arrival of navigators who would transform these biological corridors into highways of culture.