East Melanesia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 70 total

Melanesia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Sahulian Highlands, Volcanic Arcs, and the Unpeopled Frontiers of Remote Oceania

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the height of the Late Pleistocene glaciation, Melanesia was divided into two very different worlds:

-

The western realm, including New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the northern Solomons (Bougainville–Buka)—all part of the larger Sahul continent joined to Australia by the exposed Torres Shelf.

-

The eastern realm, the isolated island chains of Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the central–eastern Solomons (Guadalcanal–Malaita–Makira–Santa Cruz)—the volcanic and coral highlands of Remote Oceania, still uninhabited by humans.

Sea level lay roughly 100 meters below present, exposing broad continental shelves in the west and narrowing reef lagoons in the east. The Sahulian landmass extended north into Arafura–Carpentaria plains, while New Guinea’s central ranges rose into glaciated heights with periglacial basins and frost-prone valleys.

To the east, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia stood as isolated volcanic arcs emerging steeply from deep basins—ecologically rich but geographically inaccessible to the foragers of the western coasts.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Glacial World (49–30 ka):

Mean sea-surface temperatures across the Southwest Pacific were 2–3 °C cooler. Trade winds strengthened, intensifying upwelling on leeward coasts and bringing drier conditions to New Guinea’s highlands and valleys. The Central Cordillera supported small alpine glaciers, and montane forests gave way to open grassland and subalpine scrub. -

Toward the LGM (~30–28 ka):

Aridity peaked; coastal mangroves retreated; many lowland rivers cut deeply into exposed continental shelves. Cyclones and volcanic activity persisted episodically across the arc from New Britain to Fiji. -

Regional Contrast:

Western Melanesia retained significant rainfall and river flow, while Remote Oceania remained wetter overall but climatically cooler and more seasonally variable.

Western Melanesia: The Sahulian Heart

By this epoch, modern humans had long been established in New Guinea and the Bismarcks, forming one of the world’s most enduring highland–lowland adaptations.

-

Subsistence & Settlement

Foragers occupied glacial uplands such as the Ivane Valley (Central Highlands) and Kafiavana, where hearths, stone flakes, and grindstones attest to cold-climate resource management—small-game hunting, nut and tuber gathering, and controlled fire use to maintain open ground.

Along the Sepik–Ramu and Papuan Gulf, coastal and riverine communities exploited fish, mollusks, and estuarine mammals; reef flats now stranded high and dry would later become mangrove forests.

Fire regimes reshaped highland grasslands, encouraging regrowth and visibility for marsupial hunts, while wild tubers (precursors of yam and taro) were deliberately managed in cleared patches—the world’s earliest evidence of proto-horticultural systems. -

Technology & Material Culture

Flaked quartz and chert tools dominated; ground-stone axes began to appear for woodworking. Plant-fiber nets and string bags, now perishable, were probably in common use. Ochre and hematite were employed for body painting and symbolic burials.

Shelters—rock overhangs and built windbreaks—were adapted to frost and seasonal cold. -

Movement & Interaction Corridors

River corridors (Strickland, Fly, Sepik, Ramu) served as travel and exchange routes, connecting inland valleys with coastal lowlands. Although full ocean crossings were still rare, obsidian from New Britain occasionally reached New Guinea sites, hinting at incipient seafaring competence along sheltered coasts and straits. -

Cultural & Symbolic Life

Pigment use and ritualized burials reveal social continuity and symbolic depth. Fire—both a practical and ceremonial tool—was central to highland identity and landscape management.

Eastern Melanesia: The Unpeopled Frontier

Beyond the Sahul shelf lay Remote Oceania, a vast Pacific expanse scattered with volcanic arcs and coral plateaus—Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the eastern Solomons—all still empty of human life.

-

Ecosystems and Biota

Dense rainforests and cloud forests cloaked the high islands, nourished by volcanic soils. Reef and lagoon systems were narrower at glacial lowstand but maintained robust coral and fish populations. Seabird colonies, turtles, and flying foxes dominated terrestrial fauna; large reptiles and endemic birds filled ecological niches undisturbed by mammalian predators. -

Environmental Stability

Despite cooler sea-surface temperatures, reef–lagoon productivity remained high, buffering ecosystems through climatic oscillations. Volcanic ash periodically enriched soils, supporting evergreen canopies. These landscapes matured in isolation—an ecological Eden awaiting human discovery.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Across the entire Melanesian domain, resilience stemmed from diversity and isolation:

-

In Western Melanesia, flexible foraging and fire-based ecosystem management allowed human populations to thrive through glacial extremes.

-

In Eastern Melanesia, biological systems maintained equilibrium without human influence—reefs recovered, forests recycled, and volcanoes renewed soils on cyclical timescales.

The contrast between peopled west and empty east defined Melanesia’s enduring duality: one a cradle of continuous habitation and innovation, the other a pristine wilderness preserved by distance.

Transition Toward the Holocene

By 28,578 BCE, Western Melanesian foragers had mastered every ecological zone from alpine valleys to coral flats, forming the cultural base of the later Papuan–Austronesian continuum.

To the east, volcanic and coral islands awaited the rise of sea levels and the eventual emergence of long-range voyagers.

The post-glacial world would soon redraw coastlines, creating new estuaries, lagoons, and archipelagos—the stage on which Lapita seafarers would one day appear.

But for now, Melanesia remained a divided world: the oldest continuously inhabited mountains on Earth facing a still-unpeopled Pacific horizon.

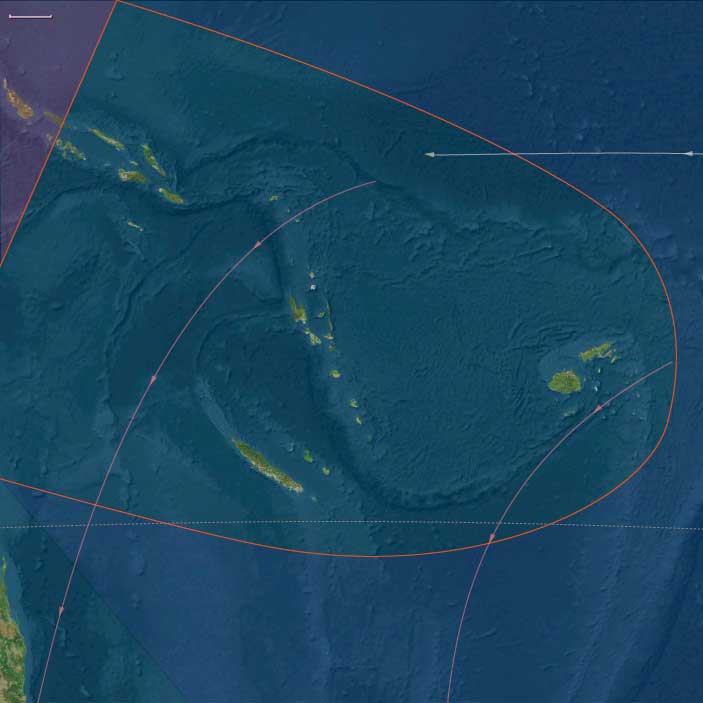

East Melanesia (49,293–28,578 BCE) Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, central/eastern Solomons

Geographic & Environmental Context

East Melanesia includes Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, central/eastern Solomons (Guadalcanal–Malaita–Makira–Santa Cruz).

Anchors: Grande Terre reef-lagoon rim (New Caledonia), Vanuatu arc volcanoes, Fiji high islands & Lau passages, Solomon trench/lagoons.

-

Remote Oceania islands rising steeply from deep basins; reef-lagoon systems narrower at lowstand; inter-island distances substantial.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

LGM: cooler SSTs, stronger trades; reduced rainfall; cyclones still episodic.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

No humans yet (Remote Oceania was not peopled until the mid-late Holocene, Lapita ~3.5 ka). Ecosystems dominated by seabirds, reef fish, and forest endemics.

Technology / Corridors / Symbolism

-

N/A (pre-human).

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Reef/lagoon productivity robust; volcanic soils accumulated under closed-canopy forests.

Transition

-

Post-LGM sea rise will build wide back-reef ponds and passes — the future stage for Lapita seafaring dispersals.

Melanesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Forests, Gardens, and the First Sea Roads

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, Melanesia—stretching from New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago to the Solomon chain, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia—underwent a profound ecological and cultural transformation.

At the Last Glacial Maximum, lowered seas fused many islands into larger landmasses. As the ice melted, rising waters fragmented coastal plains, creating the modern archipelagos and isolating highland basins.

-

West Melanesia (New Guinea, Bismarcks, Bougainville): vast valleys, expanding rainforests, and active volcanoes framed by rich reefs and mangrove deltas.

-

East Melanesia (Solomons, Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia): newly separated island chains with widening lagoons and thriving coral platforms.

By 7,800 BCE, the great Sahul–Melanesian bridge had vanished beneath the sea, leaving New Guinea and its eastern satellites distinct but still visible across narrow straits—a geography that would nurture the Pacific’s first sustained voyaging traditions.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The end of the Pleistocene brought warmer, wetter climates and the full onset of the Holocene monsoon regime:

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE): sharp warming, heavier rainfall, and glacier retreat in the New Guinea highlands; forest expansion in valleys and along coasts.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 BCE): brief cooling and drying; temporary contraction of montane forests.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): sustained warmth and humidity; stable rainfall re-established dense lowland and montane forests; coral reefs reached modern vigor.

These oscillations alternately exposed and drowned plains, prompting both adaptation in agriculture and the emergence of maritime corridors.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across Melanesia, lifeways diversified as people adjusted to deglaciation and expanding tropical biomes:

-

Highlands of New Guinea:

The Kuk Swamp system began forming precursors to drainage channels by c. 10,000–9,000 BCE. Here, people managed taro, banana, yam, and sugarcane, creating the world’s earliest known horticultural landscapes. Seasonal settlements along valley margins indicate growing sedentarism. -

Lowlands and coasts (New Guinea & Bismarcks):

Forager–fisher–gardeners exploited shellfish, reef fish, and forest nuts (Canarium, pandanus). Mangroves and estuaries offered stable protein year-round. Arboriculture (tree crop tending) and periodic burning expanded mosaic habitats. -

Island arcs (Solomons to Fiji & New Caledonia):

Communities established semi-sedentary coastal hamlets near lagoons and estuaries, supported by broad-spectrum diets—reef fish, shellfish, bird and reptile meat, and wild roots/tubers. Evidence of nut groves and forest-edge management points to early landscape control.

Population densities remained modest, but communities were increasingly anchored to specific territories defined by reef passes, valleys, and resource-rich bays.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological innovation mirrored this dual terrestrial–marine focus:

-

Ground-stone axes and adzes emerged for forest clearance and woodworking; flaked tools persisted for finer work.

-

Obsidian from the Bismarck volcanic chain (Talasea, Lou) circulated widely—marking one of the earliest systematic exchange networks in human history.

-

Cordage, baskets, and bark containers supported mobility and food storage; shell ornaments and ochre burials continued symbolic traditions.

-

Early canoe forms—likely hollowed logs stabilized with outriggers—enabled short open-sea crossings between visible islands, laying foundations for Oceanic seafaring.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Melanesia’s fragmented geography became an engine of connection rather than isolation:

-

West Melanesia: regular crossings linked New Guinea ⇄ Bismarcks ⇄ Bougainville, distributing obsidian, shell, and forest products.

-

East Melanesia: expanding inter-island voyaging joined Solomons ⇄ Vanuatu ⇄ Fiji ⇄ New Caledonia, forming a maritime network that prefigured later Remote Oceania circuits.

-

Highland–lowland exchange systems traded salt, stone, and forest goods for marine shells and pigments.

This dynamic flow of goods and knowledge marked the first sustained inter-island navigation in the Pacific realm.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Cultural expression blossomed with environmental security:

-

Rock art traditions flourished in New Guinea valleys and island caves—depicting fauna, geometric patterns, and spirit figures linked to fertility and ancestry.

-

Ochre use in burials, shell jewelry, and carved bone objects reflected ritual continuity.

-

The integration of forest and sea cosmologies—mountain spirits, ancestor shells, water serpents—rooted identity in ecological abundance and exchange.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience derived from diversified subsistence and land–sea integration:

-

Horticulture and arboriculture stabilized food supplies amid shifting rainfall and rising seas.

-

Reef harvesting and lagoon fisheries ensured high protein availability even in climatic downturns.

-

Voyaging alliances between neighboring islands offset local resource failures and cemented social ties.

-

Forest regrowth management through selective clearing and fire maintained balance between cultivation and wild biodiversity.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Melanesia stood as one of humanity’s most sophisticated forager–horticultural regions:

-

In West Melanesia, the New Guinea highlands had pioneered swamp cultivation and forest management—among the world’s earliest farming systems.

-

In East Melanesia, inter-island voyaging and lagoon-based economies anticipated the maritime adaptations of later Lapita and Polynesian cultures.

Together, they defined a dual legacy—gardens of earth and gardens of sea—rooted in innovation, mobility, and ecological reciprocity that would shape Pacific civilization for the next ten millennia.

East Melanesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Paleolithic II — Deglaciation, Forest Intensification, and Inter-Island Voyaging

East Melanesia includes Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the Solomon Islands (excluding Bougainville, which belongs to West Melanesia).

-

Anchors: the Vanuatu chain (Efate, Espiritu Santo, Malekula, Tanna), the Fiji group (Viti Levu, Vanua Levu, Lau islands), New Caledonia (Grande Terre, Loyalty Islands), and the central/eastern Solomons (Guadalcanal, Malaita, Makira, Santa Cruz).

-

Rising seas fragmented lowland plains into the modern archipelagos.

-

Coral reef accretion surged during warming periods.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød warming boosted rainfall and reef productivity.

-

Younger Dryas reversed briefly; Early Holocene warming stabilized environments.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Expanded broad-spectrum diets: shellfish, reef fish, nuts, tuberous roots.

-

Seasonal settlements near estuaries and reef passes; evidence of increased sedentism.

-

Bird and reptile hunting added to diets.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Improved flake and adze production; ground stone emerges.

-

Shell ornaments; early canoe forms likely used for inter-island hops (Solomons to Vanuatu).

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Expanding seafaring capacity enabled colonization of Remote Oceania outliers (Santa Cruz, Reef Islands).

-

Seasonal voyaging tied New Caledonia–Vanuatu–Fiji shelves into a circuit.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Shell jewelry, ochre in burials, carved motifs on bone/stone objects.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Increasing reliance on reefs and nut forests provided resilience to deglacial sea-level changes.

Transition

By 7,822 BCE, East Melanesia hosted semi-sedentary forager–horticultural precursors, bridging Pleistocene mobility and Holocene intensification.

Central Oceania, the twelfth of the Earth’s regions centered on the South Pacific Ocean, encompasses the Hawaiian Islands, New Zealand’s North Island, and the archipelagos of Western Polynesia, Eastern Melanesia, and Eastern Micronesia. This includes groups such as French Polynesia, Tonga, Niue, the Cook Islands, Fiji, Tokelau, Vanuatu, the eastern Solomon Islands, Nauru, Tuvalu, Samoa, and the Marshall Islands.

Its northwestern boundary separates the Solomon Islands from the easternmost islands of Papua New Guinea, including Bougainville, Buka, and several outlying islands and atolls historically known as the Northern Solomons.

The southeastern boundary divides West Polynesia, which includes the Big Island of Hawaii, from East Polynesia, represented by the Pitcairn Islands and Easter Island.

HistoryAtlas contains 399 entries for Central Oceania from the Paleolithic period to 1899.Narrow results by searching for a word or phrase or select from one or more of a dozen filters.

There is no evidence of human beings having lived in Oceania before about 31,000 BCE.

If they did, they would have lived along the coasts of the various small islands, and evidence would have long since disappeared below the rising seas of the Holocene Epoch.

Melanesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Gardens of Beginnings and Seas of Exchange

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Early Holocene, Melanesia—stretching from the Papuan highlands and Bismarck Archipelago through the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia—stood at the heart of a tropical world newly stabilized after the great glacial melt.

Rising seas sculpted the modern outlines of island chains, transforming once-connected landmasses into archipelagic corridors rich in lagoons, mangroves, and estuaries.

Inland, warm and wet conditions regenerated dense montane and coastal forests, while offshore reefs thrived in calm, sunlit waters.

Two broad zones matured in tandem:

-

West Melanesia, dominated by the New Guinea highlands and the Bismarck islands, where human innovation began to reshape wetlands and forest clearings into managed gardens.

-

East Melanesia, encompassing Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the central–eastern Solomons, where communities along lagoons and reefs developed rich mixed economies and strengthened maritime linkages.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Early Holocene thermal optimum (roughly 8,000–6,000 BCE) brought warmer, wetter conditions with little interannual instability.

Rainfall was regular, fueling perennial streams and stabilizing soils in both highlands and islands.

Forests expanded upslope; coastal plains, now flooded by postglacial seas, hosted mangroves and estuaries.

Volcanic activity refreshed landscapes in the Bismarck and Vanuatu–Fiji arcs, providing fertile ash for rapid regrowth.

This equilibrium fostered one of the earliest and most enduring forest–garden ecologies on Earth.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across Melanesia, communities transitioned from mobile foraging to semi-sedentary horticultural lifeways grounded in wetland and forest productivity:

-

West Melanesia (New Guinea & the Bismarcks):

The Kuk Swamp complex in the Wahgi Valley saw the world’s earliest ditch-fed horticulture, cultivating taro, yam, and banana in managed plots by 7,000 BCE.

Coastal and lowland groups balanced shellfish and reef fishing with nut and fruit harvests (Canarium, pandanus, breadfruit).

Highland–lowland exchange networks moved stone, salt, tubers, and forest products through expanding social spheres. -

East Melanesia (Solomons, Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia):

Large, recurrent lagoon-side villages emerged, supported by shellfish, reef fish, and forest foraging.

People began tending wild yam and taro stands, transplanting useful plants near dwellings.

Canarium nut and palm exploitation intensified, integrating coastal and inland resource cycles.

These communities lived in a rhythm of harvest, fallow, and return—early forms of land tenure rooted in the continuity of place.

Technology & Material Culture

Material life reflected both refinement and experimentation:

-

Ground-stone adzes and polished axes appeared widely, used for forest clearing and canoe building.

-

Shell and bone fishhooks, net sinkers, and woven traps reveal specialization in lagoon and reef fisheries.

-

Digging sticks and wooden spades complemented early horticulture.

-

Pottery was still absent, but ochre, beads, and ornaments point to established symbolic practices.

-

In the Bismarcks, obsidian from Talasea and Lou Island moved hundreds of kilometers via canoe, forming one of the world’s earliest long-distance exchange systems.

-

Canoe technology advanced rapidly: dugouts with simple outriggers enabled regular inter-island contact and cargo transport.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Melanesia’s geography encouraged movement rather than isolation.

-

In West Melanesia, coastal and riverine networks linked highland farmers to island voyagers: shells, salt, and obsidian moved inland, while tubers and forest goods traveled seaward.

-

In East Melanesia, voyaging circuits bound Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the central Solomons into a shared cultural horizon, visible in tool styles and obsidian sourcing.

These connections established a maritime and overland trade lattice, precursor to the later Lapita sphere that would unite the entire southwest Pacific.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Spiritual life was anchored in ancestry, place, and the rhythms of abundance:

-

Burials with shell beads, ochre, and ornaments suggest reverence for lineage and continuity of land.

-

Shell-midden feasts at lagoon settlements marked seasonal harvests and reaffirmed community bonds.

-

Rock art in highland shelters and island caves depicted fauna, hand stencils, and linear motifs, linking hunting, ritual, and fertility.

-

Ritual clearings at swamps and river mouths symbolized renewal, the human act of ordering water and soil echoing cosmic creation myths yet to be recorded.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Melanesian societies engineered resilience through diversification and exchange:

-

Mixed economies—combining gardening, nut and fruit collection, and reef foraging—smoothed seasonal shortfalls.

-

Ditch and drainage systems in wetlands prevented crop loss from flooding.

-

Inter-island voyaging acted as insurance, enabling mutual aid during storms or volcanic failure.

-

Forest management through selective clearing and fallow maintained biodiversity and soil fertility.

These strategies embedded human livelihood into the self-renewing cycles of the forest and sea.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Melanesia had become a fully articulated horticultural and maritime system—one of the earliest centers of food production on the planet.

From the Kuk Swamp gardens to the Fiji–Vanuatu exchange arcs, communities combined stability with exploration, their networks stretching from mountain valleys to open seas.

The region’s enduring legacy was a cultural ecology of balance: gardens rooted in volcanic soil, canoes crossing lagoons, and communities attuned to both land and tide—an enduring pattern that would carry Melanesia into the Lapita horizon and beyond.

East Melanesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Semi-Sedentary Villages and Root Crop Precursors

Geographic & Environmental Context

East Melanesia includes Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the Solomon Islands (excluding Bougainville, which belongs to West Melanesia)

-

Anchors: the Vanuatu chain (Efate, Espiritu Santo, Malekula, Tanna), the Fiji group (Viti Levu, Vanua Levu, Lau islands), New Caledonia (Grande Terre, Loyalty Islands), and the central/eastern Solomons (Guadalcanal, Malaita, Makira, Santa Cruz).

-

Islands now close to modern outlines; productive reefs and rich volcanic valleys.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Early Holocene thermal optimum: wetter, warmer conditions favored dense forests.

-

Stable rainfall supported perennial streams and fertile alluvial fans.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Foragers became more semi-sedentary, with recurring large sites near lagoons.

-

Early tending of yams, taro, bananas from wild stands; nut harvesting intensified (Canarium, Pandanus).

-

Shellfish middens expanded; inland foraging integrated with coast.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Pottery absent; ground stone and shell adzes common; net sinkers, fishhooks in bone/shell.

-

Early canoe innovation: dugouts with outrigger precursors.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Regular inter-island voyaging evident between Vanuatu–Fiji–Solomons; obsidian moved from Banks Islands into wider networks.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Burial sites with grave goods (shell beads, ornaments); persistent use of ochre.

-

Ritualized shellfish feasting inferred from midden contexts.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Diversified reef–forest–river economies and proto-horticulture buffered resource shocks.

Transition

By 6,094 BCE, East Melanesia displayed a mixed economy and strong voyaging links—precursors of the later Lapita horizon.

There is no evidence of settlement in the islands of Oceania during the Neolithic period; it will not be until around three thousand years before the present that the ancestors of the Melanesian and Polynesian peoples will arrive to settle the many tiny, far-flung islands of this vast watery region.

Melanesia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Gardens of Exchange and the Obsidian Sea

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Middle Holocene, Melanesia formed a densely interconnected realm of volcanic mountains, coral-fringed coasts, and deep forest valleys, stretching from the highlands of New Guinea through the Bismarck Archipelago to the chains of the Solomons, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia.

By this time, sea levels had stabilized near their Holocene highstand, producing extensive estuarine lagoons and widening lowland plains. The landscape combined swamp-fed gardens, reef-bordered villages, and dense tropical forests punctuated by managed clearings.

The region’s geography was already an intricate ecological web: highland cultivation linked to coastal arboriculture, inland valleys to outer reefs, and volcanic uplands to fertile alluvia. These environments laid the foundation for one of the world’s oldest systems of sustained agroforestry and exchange.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm phase brought climatic stability with consistent rainfall and minimal cold-season variability.

High humidity and nutrient-rich volcanic soils favored dense vegetation growth and extended cropping cycles. Highland basins remained perennially wet, ideal for taro and banana cultivation, while lower coastal zones supported breadfruit, yam, and pandanus groves.

Occasional volcanic activity enriched soils, and periodic El Niño–type oscillations may have influenced rainfall but without long-term disruption. Overall, this was a warm, wet, and productive equilibrium that sustained continuous human occupation and innovation.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across Melanesia, societies developed highly organized horticultural systems blending agriculture, arboriculture, and foraging:

-

In the New Guinea highlands, ditch-fed taro and banana gardens spread across valley floors, evolving into the swamp-terrace agriculture seen at sites like Kuk.

-

Along the Papuan Gulf and northern coasts, pigs and chickens began to appear, complementing fishing, sago processing, and small-scale gardening.

-

In the Bismarck and Solomon Islands, village clusters with permanent house foundations and shell middens marked stable, long-term settlement.

-

Further east, in Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia, villagers maintained yam and taro plots interwoven with Canarium nut groves—an early form of agroforestry mosaic management.

Subsistence was diversified: reef fishing, nut gathering, and cultivated starches formed complementary systems. These were landscapes already under continuous human design—managed, productive, and resilient.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological sophistication kept pace with environmental abundance.

Ground-stone adzes, polished axes, and grinding slabs proliferated across the islands, supporting intensive wood- and canoe-working. Barkcloth (tapa) manufacture likely originated in this era, used for clothing and ritual.

The obsidian trade flourished: high-quality glass from New Britain’s Talasea sources, Manus, and the Banks and Santa Cruz Islands circulated through hundreds of kilometers of sea routes, forming one of the earliest long-distance exchange networks on Earth.

These systems foreshadowed the Lapita horizon, in which pottery, obsidian, and navigation would unite Melanesia into a single cultural sphere.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The Middle Holocene witnessed the full emergence of maritime Melanesia.

Canoe technologies evolved—outrigger stability systems and improved lashings—enabling confident inter-island travel.

Regular trade circuits connected:

-

The Bismarcks and Bougainville, hubs of obsidian distribution and pig exchange.

-

The Solomons, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia, linked by networks that shared nut crops, shell ornaments, and ritual goods.

-

Highlands and coasts, joined by river valleys and mountain passes through which stone tools, salt, and forest produce moved.

These routes integrated Melanesia into a single economic continuum—a web of seaways and pathways that transformed geography into community.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Ritual life reflected both ancestral veneration and social cooperation.

Burial practices often placed the dead beneath house floors or within village precincts, emphasizing continuity between household and lineage.

Feasting traditions—centered on yam harvests, pig slaughter, and nut collection—strengthened alliances and redistributed surplus.

Early rock art in the Bismarck and Solomon Islands depicted cultivation, canoes, and ritual figures, while shell jewelry and decorated adzes served as prestige symbols within exchange systems.

These expressive forms reveal societies where ritual and subsistence were inseparable—each feast, voyage, and garden plot an act of renewal.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Melanesian communities engineered ecological stability through diversity and reciprocity.

-

Highland ditch systems controlled flooding and maintained soil fertility.

-

Coastal arboriculture buffered against cyclone damage.

-

Multi-island alliances provided insurance against local reef or crop failure, exchanging surplus across ecological zones.

This distributed risk strategy—horticulture + arboriculture + exchange—created one of the most resilient systems in the prehistoric world, balancing sustainability with innovation.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Melanesia stood as a mature horticultural–exchange civilization in everything but name.

Its communities had mastered the interplay of earth and ocean, turning volcanic instability and archipelagic fragmentation into engines of cultural coherence.

Obsidian routes stitched the region together, and managed landscapes—swamps, gardens, nut groves, and reef fisheries—functioned as enduring ecological and social systems.

The stage was set for the Lapita expansion and the later spread of Austronesian languages, technologies, and voyaging traditions.

This was the epoch when Melanesia became the living heart of the western Pacific, where gardens, ancestors, and canoes together defined the human mastery of the tropical sea.