Northeastern Eurasia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 192 total

As humans develop more advanced skills and techniques, evidence of early construction begins to emerge.

Fossil remains of Cro-Magnons, Neanderthals, and other Homo sapiens subspecies have been found alongside foundation stones and stone pavements arranged in the shape of houses, suggesting a shift toward settled lifestyles and increasing social stratification.

In addition to building on land, early humans also develop seafaring technology. The proto-Australians appear to be the first known people to cross open water to an unseen shore, ultimately peopling Australia—a remarkable achievement in early maritime exploration.

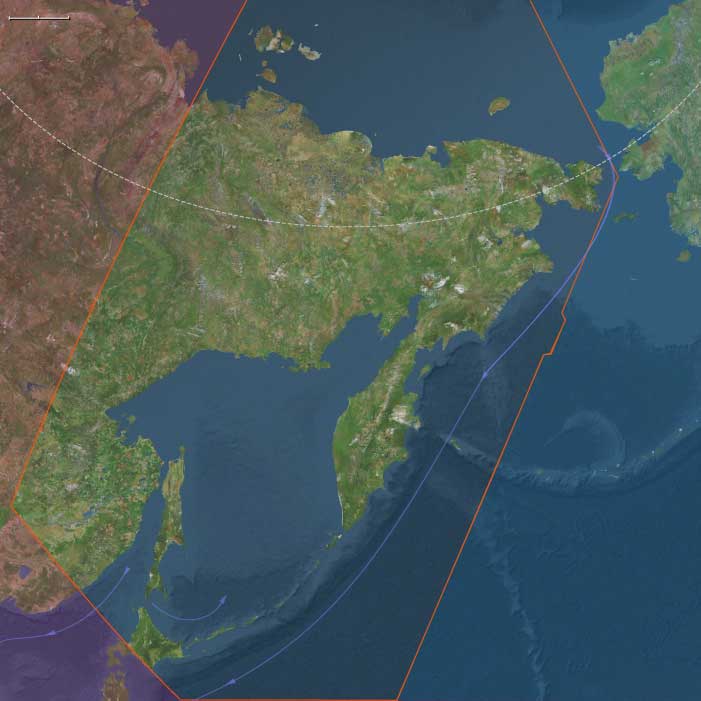

Northeastern Eurasia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Beringian Migrations, Salmon Economies, and the First Pottery Traditions

Geographic & Environmental Context

At the end of the Ice Age, Northeastern Eurasia—stretching from the Urals to the Pacific Rim—was a vast, deglaciating world of river corridors, boreal forests, and emerging coasts. It included three key cultural–ecological spheres:

-

Northwest Asia — the Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei heartlands, Altai piedmont lakes, and Minusinsk Basin, bounded by the Ural Mountains to the west. Here, deglaciation produced pluvial lake systems, and forest belts climbed into the Altai foothills.

-

East Europe — from the Dnieper–Don steppe–forest margins to the Upper Volga–Oka and Pripet wetlands, a corridor of interlinked rivers and pluvial basins supporting rich postglacial foraging.

-

Northeast Asia — the Amur and Ussuri basins, the Sea of Okhotsk littoral, Sakhalin and the Kuril–Hokkaidō arc, Kamchatka, and the Chukchi Peninsula—a maritime–riverine realm where early Holocene foragers developed salmon economies and pottery traditions under the warming Pacific westerlies.

Together these subregions formed a continuous arc of adaptation spanning tundra, taiga, and coast—an evolutionary laboratory for the technologies and traditions that would later circle the entire North Pacific.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød (14,700–12,900 BCE): Rapid warming and higher precipitation expanded boreal forests and intensified riverine productivity across Eurasia’s north. Salmon runs strengthened in the Amur and Okhotsk drainages; pluvial lakes filled the Altai basins.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 BCE): A temporary cold–dry reversal restored steppe and tundra, constraining forests to valleys; lake levels fell; inland mobility increased.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): Stable warmth and sustained moisture drove forest advance (pine, larch, birch) and high lake stands; sea levels rose along the Okhotsk and Bering coasts, flooding older plains and establishing modern shorelines.

These oscillations forged adaptable forager systems able to pivot between large-game mobility and aquatic specialization.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across the northern tier, lifeways diversified and semi-sedentism began to take root:

-

Northwest Asia:

Elk, reindeer, beaver, and fish formed broad-spectrum diets. Lakeside camps in the Altai and Minusinsk basins became seasonal home bases, while Ob–Yenisei channels hosted canoe or raft mobility. Forest nuts and berries expanded plant food options in warm phases. -

East Europe:

Along the Dnieper, Don, and Upper Volga, foragers targeted elk, red deer, horse, and beaver, exploiting riverine fish and waterfowl. Repeated occupations at lake outlets and confluences reflect increasing site permanence and food storage. -

Northeast Asia:

The Amur–Okhotsk region pioneered salmon-based economies, anchoring early Holocene villages at river confluences and estuarine terraces. Coasts provided seal, shellfish, seabirds, and seaweeds, while inland foragers pursued elk and musk deer. Winter sea-ice hunting alternated with summer canoe travel along the Sakhalin–Kuril–Hokkaidō chain.

This mosaic of economies—lake fishers, river hunters, and sealers—reflected the continent’s growing ecological diversity.

Technology & Material Culture

Innovation was continuous and regionally distinctive:

-

Microblade technology persisted across all subregions, with refined hafting systems for composite projectiles.

-

Bone and antler harpoons, toggling points, and gorges evolved for intensive fishing and sealing.

-

Ground-stone adzes and chisels appeared, enabling woodworking and boat construction.

-

Early pottery, first along the Lower Amur and Ussuri basins (c. 15,000–13,000 BCE), spread across the Russian Far East—among the world’s earliest ceramic traditions—used for boiling fish, storing oils, and processing nuts.

-

Slate knives and grindstones at Okhotsk and Amur sites show specialized craft economies.

-

Personal ornaments in amber, shell, and ivory continued, while sewing kits with eyed needles and sinew thread supported tailored, waterproof clothing.

These toolkits established the technological template for later northern and Pacific Rim foragers.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei river systems funneled movement north–south, linking the steppe with the taiga and tundra.

-

Altai and Ural passes maintained east–west contact with Central Asia and Europe.

-

Dnieper–Volga–Oka networks merged the European forest-steppe into the greater Eurasian exchange field.

-

In the Far East, the Amur–Sungari–Zeya–Okhotsk corridor unified interior and coast, while the Sakhalin–Kuril–Hokkaidō arc allowed short-hop voyaging.

-

Across the Bering Strait, fluctuating sea levels intermittently connected Chukotka and Alaska, maintaining Beringian gene flow and cultural exchange.

These conduits supported both biological and technological diffusion at a continental scale.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Ochre burials with ornamented clothing and ivory or antler goods reflect deep symbolic continuity from the Upper Paleolithic.

-

Petroglyphs and engravings in the Altai and Minusinsk basins, and later in Kamchatka, depict large animals, waterbirds, and solar motifs.

-

Amur basin figurines and carved marine-mammal and fish effigies attest to ritualized relationships with food species.

-

In the Far East, early evidence of first-salmon and bear-rite traditions foreshadows later Ainu and Okhotsk ceremonialism.

Across all subregions, water and game remained the core of spirituality, connecting people to cyclical abundance and ancestral landscapes.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Foragers across Northeastern Eurasia met environmental volatility with creative versatility:

-

Zonal mobility (taiga–tundra–coast) and multi-season storage (dried meat, smoked fish, rendered oils) stabilized food supply.

-

Boat and ice technologies extended reach across seasons.

-

Broad-spectrum diets cushioned against climatic downturns.

-

Flexible dwellings and social alliances allowed fission and fusion as resources shifted.

-

Memory landscapes—engraved rocks, ritual mounds, named rivers—preserved continuity through spatial change.

Genetic and Linguistic Legacy

The Beringian population standstill during the Late Glacial created a deep ancestral pool for both Paleo-Inuit and First American lineages, while reciprocal migration reconnected Chukchi, Kamchatkan, and Amur populations after sea-level rise.

These long-lived networks seeded circum-Pacific cultural parallels in salmon ritual, dog-traction, maritime hunting, and composite toolkits, forming the northern backbone of later trans-Pacific cultural continuity.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Northeastern Eurasia had become one of the world’s great centers of forager innovation:

-

Northwest Asia’s pluvial lakes fostered early semi-sedentism and the first rock art of Siberia.

-

East Europe’s river–lake foragers stabilized broad-spectrum economies bridging steppe and forest.

-

Northeast Asia’s salmon-rich coasts and early pottery traditions created the technological and ritual matrix that would radiate across the North Pacific.

This continental synthesis of aquatic resource mastery, ceramic innovation, and long-range mobility defined the emerging Holocene north—a zone where people and landscape adapted together through water, ice, and memory.

Northeast Asia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Paleolithic II — Beringian Standstill, Early Pottery Horizons, and Salmon Towns

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northeast Asia includes eastern Siberia east of the Lena River to the Pacific, the Russian Far East (excluding the southern Primorsky/Vladivostok corner), northern Hokkaidō (above its southwestern peninsula), and extreme northeastern Heilongjiang.

-

Anchors: the Lower/Middle Amur and Ussuri basins, the Sea of Okhotsk littoral (Sakhalin, Kurils), Kamchatka, the Chukchi Peninsula (with Wrangel Island offshore), northern Hokkaidō, and seasonally emergent shelves along the Bering Sea and northwest Pacific.

Climatic Crisis and Population Transformation During the LGM

Between roughly 28,500 and 20,000 years ago, the onset of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) profoundly altered Northeast Asia. Ice sheets, permafrost expansion, and ecological fragmentation reduced habitable zones across Siberia.

During and immediately after this period, the Ancient North Siberians were largely replaced by populations carrying ancestry closely related to East Asians. This was not a simple migration but a prolonged process of demographic turnover, admixture, and regional extinction.

Out of this transformation emerged two closely related populations:

-

Ancestral Native Americans

-

Ancient Paleosiberians (AP)

Paleoclimatic modeling strongly supports southeastern Beringia as a long-term refugium during the LGM, providing a stable ecological zone where these populations could persist, interact, and differentiate.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE): warming and moisture increase expanded boreal forest into valleys; salmon runs intensified; nearshore productivity rose.

-

Younger Dryas (c. 12,900–11,700 BCE): brief return to cooler, drier conditions; tundra patches expanded but ice-free coasts still offered reliable marine resources.

-

Early Holocene (after c. 11,700 BCE): stabilizing warmth and rising sea level reshaped shorelines; taiga expanded fully; rich riverine and estuarine habitats matured.

Subsistence and Settlement

-

Deglaciating coasts supported seal and salmon economies; intertidal shellfish beds and seabird rookeries fueled seasonal aggregation.

-

In warming phases, diets diversified toward fish (salmon, sturgeon), small game, and plant foods (nuts, roots, berries).

-

Younger Dryas prompted higher mobility and renewed emphasis on large herbivores where herds persisted.

-

Early Holocene villages favored river confluences and coastal terraces, ideal for salmon weirs and broad foraging radii.

Technology and Material Culture

-

Microblade production refined; hafted composite points standardized for hunting and sealing.

-

Bone/antler harpoons with toggling tips; barbed fishhooks; sewing kits for tailored garments and waterproof seams.

-

Early pottery appears in the Lower Amur–Russian Far East and spreads to surrounding basins—among the world’s earliest ceramic traditions—used for fish oils, stews, and nut processing.

-

Ground-stone adzes for wood-working and dugout canoe manufacture; slate knives on some Okhotsk coasts.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Amur–Sungari waterway integrated interior and coast; Sakhalin–Kuril–Hokkaidō island chain enabled short-hop voyaging.

-

Beringian standstill: populations on both sides of the strait developed long-term ties; fluctuating sea levels modulated contact.

-

Seasonal sea-ice bridges facilitated winter travel; summer lanes favored canoe movement.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

-

Carved bone and ivory figurines, zoomorphic engravings, and ochre burials persisted, signaling continuity with earlier Upper Paleolithic symbolic systems.

-

Recurrent salmon first-catch rites and bear/sea-mammal treatment practices are inferred from patterned discard and ritualized processing locales.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

-

Zonal mobility (taiga–tundra–coast) and storage (dried fish, rendered oils) buffered climate swings across Bølling–Allerød → Younger Dryas → Early Holocene.

-

Canoe technologies, fish weirs, and shoreline mapping (capes, tide rips, haul-outs) underwrote stable subsistence as forests spread and shorelines shifted.

Genetic and Linguistic Legacy

-

Prolonged Beringian population structure during late glacial–early Holocene times contributed ancestry to Paleo-Inuit and to the First Americans; reciprocal gene flow linked Chukchi–Kamchatka–Amur families.

-

These deep ties foreshadowed later circum-North Pacific cultural continuities in salmon ritual, dog-traction, and composite toolkits.

Transition Toward the Holocene Forager Horizons

By 7,822 BCE, Northeast Asia featured mature taiga coasts, prolific salmon rivers, and early pottery villages—a landscape primed for the broad-spectrum, semi-sedentary foraging economies that would dominate the Early Holocene and eventually feed into Epi-Jōmon/Satsumon, Okhotsk, and Amur basin cultural florescences.

Mitochondrial haplogroups A, B, and G originated fifty thousand years ago, and the bearers subsequently colonized Siberia, Korea and Japan, by thirty five thousand years ago.

Parts of these populations migrate to North America.

Beringia, the so-called Bering Land Bridge, extends in 18,000 BCE from the Aleutian chain’s Unalaska Island on the southeast, northwestward to the Koryak area’s Cape Olyutorsky north of the Kamchatka Peninsula, and from near the mouth of Canada’s Mackenzie River on the east to near eastern Siberia’s Kolyma and Indigirka rivers on the west.

The sea would long ago have claimed most evidence of temporary or permanent occupation by pre-Holocene peoples.

An alternate, or parallel theory, roiginally proposed in 1979 by Knute Fladmark as an alternative to the hypothetical migration through an ice-free inland corridor, has the first immigrants moving down the coastlands by boat.

Northeastern Eurasia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Salmon Rivers, Pottery Frontiers, and Forest–Sea Corridors

Geographic & Environmental Context

From the Upper Volga–Oka and Dnieper–Pripet belts across the Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei to the Amur–Ussuri and the Okhotsk–Bering rim (Sakhalin, Kurils, Kamchatka, Chukchi, northern Hokkaidō), Northeastern Eurasia formed a continuous world of taiga, big rivers, and drowned estuaries. Sea level rise reshaped river mouths into productive bays and tidal flats; inland, lake chains and marshlands multiplied along stabilized watersheds.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal optimum brought warmer, wetter, and more even seasonality.

-

Taiga expansion (birch–pine–spruce) advanced north; mixed forests with hazel spread south.

-

Rivers (Volga, Dnieper, Ob, Yenisei, Amur) ran full but steady; estuaries and kelp-lined nearshore waters boomed.

-

Rising seas drowned river mouths, creating ideal passages for anadromous salmon and shellfish-rich flats.

These conditions favored semi-sedentary clustering at confluences, terraces, and tidal margins.

Subsistence & Settlement

A pan-regional broad-spectrum, storage-oriented foraging system matured:

-

East Europe (Upper Volga–Oka, Dnieper, Upper Dvina, Pripet): semi-sedentary river villages with pit-houses focused on sturgeon/pike, elk/boar, hazelnuts, and berries; net-weirs and fish fences anchored seasonal peaks.

-

Northwest Asia (Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei, Altai–Minusinsk): riverine hamlets hunted elk, reindeer, boar; salmon and sturgeon fisheries underwrote wintering; hearth clusters and storage pits marked long occupation.

-

Northeast Asia (Lower/Middle Amur–Ussuri, Okhotsk littoral, Sakhalin–Kurils–Hokkaidō, Kamchatka, Chukchi): salmon-focused semi-sedentism at confluences and tidal flats; smoke-drying and oil rendering produced high-calorie stores; broad-spectrum rounds added elk/reindeer, waterfowl, intertidal shellfish, and seasonal pinnipeds.

Across the span, households returned to the same terraces, bars, and headlands, building place-memory landscapes suited to storage and exchange.

Technology & Material Culture

This was the first great pottery horizon of the north, paired with refined fishing and woodcraft:

-

Early ceramics (7th millennium BCE onward): fiber-/plant- or grit-tempered jars spread in the Upper Volga–Oka, Ob–Yenisei, and Lower Amur, used for boiling fish/meat, fat rendering, and storage; soot-blackened cookpots are typical in the Amur basin.

-

Ground-stone adzes/axes drove canoe- and house-carpentry; composite harpoons, barbed bone hooks, gorges, net sinkers/floats, and stake-weirs scaled mass capture.

-

Personal ornaments of shell, amber, antler, and drilled teeth traveled widely; ochre accompanied burials.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Waterways made a braided superhighway:

-

Volga–Oka–Dnieper–Dvina canoe circuits linked taiga, marsh, and lake belts; portages stitched watersheds and spread pottery styles.

-

Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei integrated western and central Siberia; the Ural corridor connected taiga foragers with the forest-steppe of Europe.

-

Amur–Sungari tied interior to coast; short-hop voyaging along Sakhalin–Kurils–Hokkaidō moved shell, stone, and ideas; over-ice travel on inner bays persisted in winter.

These lanes provided redundancy—if a salmon run failed locally, neighboring reaches or coastal banks supplied substitutes.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

A river-and-animal cosmology left vivid traces:

-

Rock art fields (Minusinsk, Tomsk, Karelia–Alta–Finland) depict elk, fish, boats, hunters, and ritual poses.

-

First-salmon rites are inferred in patterned discard and special hearths; bear and sea-mammal treatments suggest respect for “animal masters.”

-

Cemeteries with ochre, antler and stone grave goods, and—in the northeast—pots in burials formalized ancestry tied to landing places and weirs.

Waterfront mounds and shell/bone-rich zones functioned as ancestral monuments.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience rested on storage + mobility + multi-habitat rounds:

-

Smoke-dried fish, rendered oils, roasted nuts/berries, and cached meats carried camps through winter.

-

River–coast–upland scheduling diversified risk across salmon runs, waterfowl peaks, reindeer/elk migrations, and shellfish seasons.

-

Weir and landing-place tenure, reinforced by ritual, regulated pressure on key stocks and limited conflict.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Northeastern Eurasia had consolidated into a storage-rich taiga and salmon civilization without agriculture—large, long-lived villages on river terraces and tidal flats; early pottery embedded in daily subsistence; and canoe/ice corridors knitting thousands of kilometers.

These habits—fat economies, ceramic storage, engineered fisheries, and shrine-marked tenure—prepared the ground for larger pit-house villages, denser coastal networks, and, later, steppe–taiga exchanges that would link this northern world to Eurasia at large.

Northeast Asia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Salmon Villages, First Pottery Expansion, and Forest Mosaics

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northeast Asia includes eastern Siberia east of the Lena River to the Pacific, the Russian Far East (excluding the southern Primorsky/Vladivostok corner), northern Hokkaidō (above its southwestern peninsula), and extreme northeastern Heilongjiang.

-

Anchors: the Lower/Middle Amur and Ussuri basins, the Sea of Okhotsk littoral (Sakhalin, Kurils), Kamchatka, the Chukchi Peninsula (with Wrangel Island offshore), northern Hokkaidō, and seasonally emergent shelves along the Bering Sea and northwest Pacific.

Formation of Ancient Paleosiberians and Proto-Amerindian Isolation

By the early Holocene, the Ancient Paleosiberians (AP) had become a distinct population across parts of northeastern Siberia. A key representative comes from a ~9,800 BCE individual from the Kolyma River, whose genome reveals close affinity to the ancestors of Native Americans.

At this stage, the populations ancestral to Native Americans and those remaining in Northeast Asia were still closely related, sharing a mixed ancestry composed of:

-

Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) components of largely West Eurasian origin

-

A deeply diverged East Eurasian lineage, related to but separate from modern East Asians, which had split from their ancestors around 25,000 years ago

This period marks the height of genetic continuity between Siberian and proto-American populations, just before their historical trajectories diverged.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Early Holocene stability: fuller taiga expansion, high river discharges, productive estuaries and nearshore kelp forests.

-

Sea level rising toward modern shorelines created drowned river-mouths ideal for salmon runs.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Salmon-focused semi-sedentism: repeated aggregation at confluences and tidal flats; smoke-drying and oil rendering supported storage.

-

Broad-spectrum foraging: elk/reindeer, waterfowl, nuts/berries, intertidal shellfish; pinnipeds seasonally.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Early pottery (fiber- and plant-tempered) spread throughout the Lower Amur and coastal basins; soot-blackened cooking jars for fish broths.

-

Ground-stone adzes for woodworking and hollowing logs; composite harpoons; barbed bone fishhooks; net sinkers and floats.

-

Personal ornaments in shell/antler; ochre-rubbed burials.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Amur–Sungari waterway linked interior and coast; short-hop voyaging along Sakhalin–Kurils–Hokkaidō.

-

Seasonal over-ice travel persisted on inner bays; summer canoe movement expanded.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

First-salmon rites inferred from patterned discard; bear and sea-mammal treatment suggests ritual respect for “animal masters.”

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Storage + mobility strategy buffered lean runs; multi-habitat rounds (river–coast–upland) diversified risk.

Transition

Toward 6,094 BCE, stable salmon ecologies and expanding early pottery paved the way for larger pit-house villages and richer coastal networks.

Northeastern Eurasia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Rivers of Salmon, Forests of Memory, and the First Great Pottery Webs

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Middle Holocene, Northeastern Eurasia—stretching from the Ural Mountains and West Siberian rivers through the Yenisei–Lena basins to the Amur Valley, Okhotsk coast, Sakhalin, Kamchatka, and northern Hokkaidō—was a vast world of taiga, tundra, and riverine abundance.

The Hypsithermal climatic optimum transformed this immense territory into a richly productive mosaic of mixed forest, grass-steppe, and salmon-bearing rivers.

In the west, the Ob–Irtysh and Yenisei basins anchored stable fishing and forest economies; eastward, the Amur and Okhotsk corridors linked river valleys to the Pacific; northward, glacial meltwaters fed chains of lakes and wetlands teeming with life.

These were the northern heartlands of the world’s great forager–fishers, and the first to organize wide ceramic, trade, and symbolic networks that prefigured the coming age of pastoralism and metallurgy farther south.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm maximum (c. 7000–4000 BCE) brought milder winters, longer growing seasons, and higher precipitation across most of Siberia and the Russian Far East.

-

Permafrost retreated, opening new valleys to vegetation and settlement.

-

Dense taiga forests spread northward, dominated by birch, pine, and larch, while broadleaf trees (oak, elm, linden) colonized the southern basins.

-

Rivers and lakes stabilized, producing predictable salmon and sturgeon runs, as well as flourishing populations of elk, bear, and beaver.

This stable climatic envelope underwrote population growth and increasingly permanent settlement—an ecological balance that would endure for millennia.

Subsistence & Settlement

Northeastern Eurasian societies thrived on diversified, river-centered economies that balanced abundance with mobility.

-

In Northwest Asia (the Ob–Yenisei–Altai region), pit-house villages lined river terraces; fishing intensified with weirs, harpoons, and net traps. Elk and reindeer hunting remained vital, supplemented by nuts and berries.

-

In Northeast Asia (the Amur, Sakhalin, Kamchatka, and Hokkaidō zones), large semi-sedentary river and coastal villages emerged, often rebuilt repeatedly to form deep archaeological layers. Salmon runs, seal rookeries, and nut groves sustained dense populations.

-

Storage technology—ceramic containers, smokehouses, and drying racks—enabled year-round residency in many locales.

-

Dog traction facilitated winter mobility; canoes and rafts made rivers and coasts into highways of exchange.

The result was an unparalleled synthesis: fishing societies as populous and materially rich as early farmers, living by rhythm rather than scarcity.

Technology & Material Culture

This epoch saw the great flowering of pottery and woodworking across the northern world:

-

Pottery spread from the western forest-steppe to the Pacific, diversifying into Narva, Comb Ware, fiber-tempered, and corded-impressed forms. Large storage vessels enabled boiling, fermenting, and preserving fish and nuts.

-

Ground-stone tools—adzes, axes, and chisels—supported extensive carpentry, housebuilding, and canoe production.

-

Harpoons, toggling spearheads, and net weights attest to mastery of aquatic technology.

-

Bone and antler craft achieved aesthetic refinement, producing pendants, figurines, and ceremonial objects.

-

In the east, dugout canoes became standard, while obsidian from Kamchatka and Hokkaidō circulated widely.

Across this immense domain, the pottery horizon became the connective tissue of culture—the material sign of a shared northern world.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The rivers and coasts of Northeastern Eurasia formed a single network of movement and exchange:

-

The Ob–Yenisei–Lena–Amur trunklines carried pottery styles, exotic stones, and ideas over thousands of kilometers.

-

The Altai–Sayan passes and Ural valleys linked Siberia to the steppes and Central Asia, transmitting tools, pigments, and eventually herd animals.

-

Eastward, the Okhotsk Sea and Amur estuaries functioned as maritime corridors, with the Kuril–Sakhalin–Hokkaidō chain acting as an “island ladder” for shell, obsidian, and cultural traffic.

These waterborne routes united forest, tundra, and coast into one of the world’s first truly transcontinental ecological and cultural systems.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Material abundance nurtured complex symbolic and social traditions:

-

Rock art—especially in the Altai, Yenisei, and Amur regions—depicted elk, reindeer, fish, solar disks, and boats, blending hunting, shamanism, and cosmology.

-

Cemeteries with ochre, pottery, and ornaments mark the earliest formalized mortuary rites across the northern taiga.

-

Feasting middens and shell caches in the Amur and Hokkaidō zones point to social gatherings centered on salmon harvests.

-

Longhouse and pit-house clusters suggest lineage-based settlement, with spiritual ties to ancestral places reinforced through burial and ritual deposition.

These expressions reveal communities already possessing a deep sense of ancestry, landscape, and cyclical time—the spiritual architecture of later northern traditions.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Survival in this vast region depended on balance, storage, and mobility:

-

Food storage (dried fish, rendered oils, and nuts) and seasonal mobility mitigated the risk of failed runs or harsh winters.

-

Multi-resource economies—hunting, fishing, gathering—provided redundancy across ecosystems.

-

Domestic dogs and canoes extended range and flexibility.

-

Settlement clustering along ecotones (forest–river–coast) allowed access to multiple biomes.

These adaptive systems ensured that even in years of climatic stress, human communities remained secure, their resilience rooted in environmental intelligence rather than technological excess.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Northeastern Eurasia had become a continent of stable, populous, and interconnected foraging societies, its rivers and coasts lined with semi-permanent villages and its pottery traditions spanning thousands of kilometers.

The Ob–Amur cultural continuum foreshadowed later Eurasian steppe–taiga interactions, while the Amur–Hokkaidō corridor anticipated the maritime expansions of the late Neolithic and Bronze Age.

This was the age of rivers and salmon, of vast communication without cities—a world where exchange, artistry, and community thrived without agriculture.

Its enduring legacy was a model of resilient abundance, proving that civilization could begin not only in fields, but also in forests and flowing water.

Northeast Asia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Big Salmon, Big Villages, and Deepening Pottery Traditions

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northeast Asia includes eastern Siberia east of the Lena River to the Pacific, the Russian Far East (excluding the southern Primorsky/Vladivostok corner), northern Hokkaidō (above its southwestern peninsula), and extreme northeastern Heilongjiang.

-

Anchors: Amur–Ussuri terraces and levees, Okhotsk embayments, Sakhalin lagoons, Kamchatka river mouths, Hokkaidō shell-midden coasts.

Beringian Standstill and the End of a Genetic Configuration

During this interval, a subset of Proto-Amerindian Paleo-Siberians entered a prolonged phase of relative genetic isolation, often referred to as the Beringian standstill. For several millennia, these populations remained largely cut off from other Asian groups.

This isolation allowed for:

-

Independent genetic drift

-

Local adaptation to Arctic and sub-Arctic environments

-

The emergence of distinct phenotypic variation

Importantly, this genetic configuration ceased to exist within Siberia itself soon after this period. While Proto-Amerindian groups moved eastward and eventually into the Americas, Siberia underwent further demographic transformation.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Hypsithermal warm maximum: dense mixed taiga, long ice-free seasons, exceptionally large salmon runs.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Large pit-house villages on raised river benches; repeated rebuilds created deep cultural layers.

-

Seasonal satellite camps at anadromous fish bottlenecks, seal haul-outs, and berry patches.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Diversified ceramic styles (corded/impressed), larger storage vessels; ground-stone woodworking kit; broad weir/trap systems; refined toggling harpoons.

-

Dugout canoes became routine for transport and net sets; dog traction in winter travel.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Canoe trunklines along the Amur and Okhotsk inner coasts; Kuril–Hokkaidō “island ladder” facilitated obsidian and shell exchange.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Longhouse/pit-house clustering hints at lineage districts; feasting middens with prestige shell/bead caches; ochre and grave goods in formal cemeteries.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

High-capacity storage (smoked/dried salmon, rendered oils) enabled semi-sedentary lifeways; diversified procurement (elk, nuts, waterfowl) hedged against run failure.

Transition

By 4,366 BCE, the region supported durable river–coast village systems and ceramic traditions poised for late Neolithic maritime networking.

Northeastern Eurasia (4,365 – 2,638 BCE): Late Neolithic / Early Metal — Rivers of Memory, Shores of Surplus

Geographic & Environmental Context

Northeastern Eurasia formed a single, immense ecotonal arc—from the Dnieper–Don–Volga forest–steppe and broad East European lowlands, across the Ural hinge and the great Ob–Irtysh and Yenisei basins, to the Lena–Amur–Okhotsk coasts and islands of the northwest Pacific. Glacially smoothed plains graded into taiga and tundra; inland seas of forested river‐lakes gave way, in the east, to eelgrass bays, barrier spits, salmon estuaries, and island chains (Sakhalin–Kurils–Hokkaidō). Throughout, waterways were the architecture of life—rivers, portages, and straits knitted inland hunting grounds to maritime larders.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Holocene warmth lingered but trended cooler toward the 3rd millennium BCE. West of the Urals, seasonality sharpened over the forest–steppe; in Western/Central Siberia, stable regimes favored wetland expansion and predictable fish runs; along the Okhotsk rim, shorelines stabilized, and warm-phase productivity surged in salmon rivers, eelgrass meadows, and lagoon systems. Variability was felt more as a shift in timing than in magnitude—prompting fine-tuned mobility rather than wholesale re-siting.

Subsistence & Settlement

Economies were mosaic and complementary.

-

Forest and forest–steppe (East Europe): riverine forager–fishers and wetland hunters intensified fisheries and red deer/boar harvests; by the late epoch, agro-pastoral packages (cattle, cereals) touched the forest–steppe margins, creating mixed lifeways and scattered hamlets alongside enduring forager camps.

-

Western/Central Siberia (Northwest Asia): rich hunting–fishing–gathering persisted; small-scale herding (sheep/goat) entered via steppe contacts; riparian villages and dune-ridge camps managed pike, sturgeon, and waterfowl seasons.

-

Okhotsk–Amur–Hokkaidō (Northeast Asia): coastal shell-midden hamlets occupied barrier spits and river mouths; inland taiga stations tracked elk, reindeer, and furbearers. Estate-like salmon and seal stations controlled weirs and rookeries, generating surpluses that supported larger feasts and incipient ranking.

Settlement fabrics ranged from light, mobile camps to semi-sedentary villages on levees and spits; cemeteries and midden plateaus marked long-term tenure.

Technology & Material Culture

Toolkits fused woodcraft, stone, bone, and the first copper glints.

-

Carpentry & watercraft: adze-finished planks with mortise-and-tenon lashings produced capable river and coastal boats; sewn skins and plank inserts served marsh and estuary travel.

-

Fishing systems: net weirs, fish fences, composite bone harpoons, toggling points, and large smoking jars/storage vats underwrote seasonal surplus.

-

Lithics & slate: ground-slate knives and fine flint blades proliferated; obsidian circuits radiated from Hokkaidō and Kamchatka.

-

Ceramics: regional diversity (corded, impressed, combed; specialized lamps and smokers on the Pacific rim) signaled cuisine and craft identities.

-

Metals & transport: early copper ornaments and tools appeared at Ural–Altai nodes; wagons/sleds emerged on steppe margins and winter routes, widening catchment and exchange.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Rivers and coasts formed braided highways:

-

East European lowlands: Dnieper–Don–Volga–Oka–Kama trunks moved furs, fish oil, and stone; late-epoch contacts carried herding and wagon know-how into the forest–steppe.

-

Siberian basins: Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei linked interior foragers, incipient herders, and copper locales, facilitating down-the-line trade of ores and finished pieces.

-

Pacific rim: short-hop coasting between Sakhalin–Kurils–Hokkaidō, and Amur–Sungari river lanes, stitched shell, slate, and ceramic styles into a shared maritime grammar.

Across this span, portages were as critical as passes: shallow divides let people drag hulls between basins, making water the master grid of Northeastern Eurasia.

Belief & Symbolism

Cosmologies were river- and animal-centered. Bear crania deposits, salmon-offering locales, and feast middensframed reciprocity with keystone species on the Pacific rim. Inland, petroglyphs of elk, boats, sun disks, and (late) wagons animated rock faces along travel routes. Ancestor cairns and formal cemeteries multiplied near productive stations, while shell beads, tooth pendants, and carefully placed tools signaled display and emerging rank in some coastal communities.

Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience rested on tenure, timing, and redundancy:

-

Estate-like control of salmon weirs and seal rookeries regulated access and prevented over-take.

-

Seasonal rotation between river, lake, and coast dispersed risk as cooling advanced.

-

Storage technologies (smoking, drying, pits, vats) converted pulses into buffers.

-

Economic pluralism—foraging + small herds + early copper—spread vulnerability across sectors, while exchange obligations redistributed food after poor runs or harsh winters.

Long-Term Significance

By 2,638 BCE, Northeastern Eurasia had matured into a continent-scale waterworld: interior basins feeding coastal surpluses, steppe corridors seeding herding and metalwork, and maritime belts perfecting woodworking and navigation. The social and technological ligatures forged here—river logistics, specialized fisheries, light craft, copper nodalities, and (in places) ranked feasting—prepared the ground for the Bronze-Age integrations to come: steppe–taiga exchange spheres, trans-Urals metal flows, and enduring Pacific-rim culture areas knit by boats, slate, and salmon.