Micronesia

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 48 total

Micronesia (2637 – 910 BCE): Island Pioneers, Canoe Networks, and the First Oceanic Web

Regional Overview

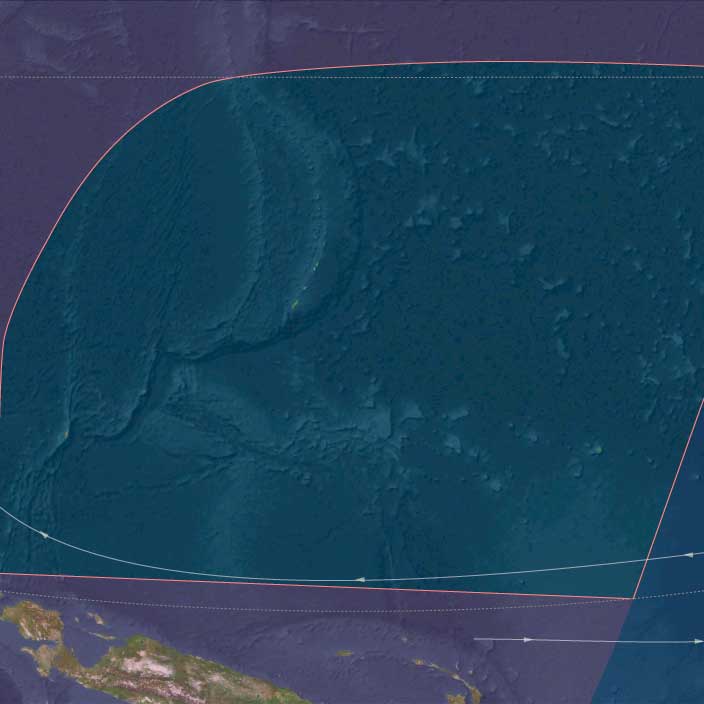

Across the western Pacific’s equatorial arc, Micronesia emerged as one of humanity’s earliest experiments in life on the open ocean.

Here, voyagers from Island Southeast Asia and the western Pacific littoral established the first permanent settlements on chains of atolls and high islands scattered across millions of square kilometers of sea.

By the early first millennium BCE, Marianas, Palau, Yap, Kiribati, the Marshalls, and Kosrae had become nodes in an expanding lattice of navigation, arboriculture, and exchange—each settlement a self-contained world, yet connected by routes of memory and stars.

Geography and Environment

Micronesia’s fragmented geography—coral atolls, uplifted limestone islands, and volcanic highlands—produced one of the planet’s most diverse maritime landscapes.

The Marianas formed the northern anchor, their volcanic soils rich but their freshwater lenses fragile.

To the south and west, the Caroline arc (Palau, Yap, Kosrae) offered volcanic relief, streams, and mangrove belts, while the Gilbert and Marshall chains stretched across the equator as low coral platforms enclosing vast lagoons.

Every environment demanded different balances of arboriculture, lagoon fishing, and rainwater harvesting.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The late Holocene climate was generally warm and stable, punctuated by ENSO oscillations that alternated drought and storm.

These cycles shaped migration, trade, and settlement spacing: atoll dwellers developed meticulous rain-catch systems and food storage to survive dry years, while high-island communities used perennial streams and valley gardens as drought refuges.

Regional variation—humid Kosrae versus arid Kiribati—encouraged ecological complementarity and exchange.

Societies and Settlement

By the mid–second millennium BCE, seafaring Austronesians had founded the Marianas, among the first islands settled beyond Near Oceania.

Their descendants established coastal hamlets, cultivated taro and breadfruit, and maintained lagoon fisheries.

In Palau and Yap, settlement followed soon after, with hamlets clustering near freshwater lenses and mangrove channels.

Eastward, settlers reached the Marshalls, Gilberts, and Kosrae, planting breadfruit and pandanus, digging swamp-taro pits, and building stilt houses at lagoon edges.

Each island or atoll became both home and harbor—a managed ecosystem engineered through arboriculture and kinship.

Economy and Technology

Micronesian economies combined tree-crop horticulture, taro cultivation, and lagoon fishing within a framework of regional trade.

Communities managed transported landscapes: coconut, breadfruit, pandanus, and taro formed the nutritional base, supplemented by turtles, fish, and shellfish.

Outrigger canoes with crab-claw sails were the principal instruments of survival, mobility, and prestige.

Shell and stone adzes, drilled fishhooks, and early tidal fish weirs reflected technological ingenuity in scarce-resource environments.

These tools, alongside elaborate knowledge of stars, swells, and cloud formations, allowed sustained navigation between islands separated by hundreds of kilometers.

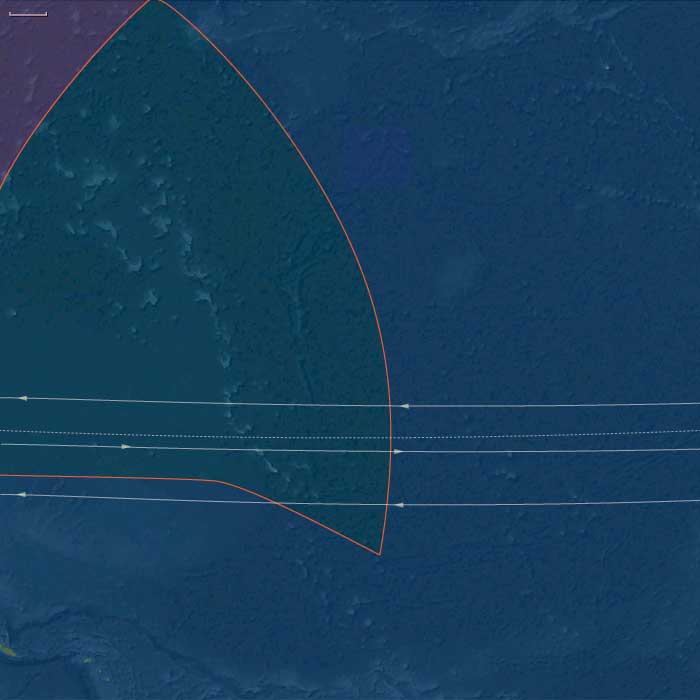

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Voyaging corridors knit the subregion into an interlinked sea.

The Ralik–Ratak pairs in the Marshalls functioned as dual atoll systems, while the Gilbert chain operated as a north–south shuttle route.

Palau connected mangrove-rich high islands with limestone islets and coral shoals, exchanging shell tools and forest products.

Yap, emerging as a high-island hub, began to organize reciprocal relationships with its outer atolls—precursors of the later sawei system.

Farther east, Kosrae linked into Carolinian navigation networks, transmitting canoe forms and ceremonial knowledge across thousands of kilometers.

Belief and Symbolism

Micronesian spirituality fused land, lineage, and sea.

Ancestral shrines stood beneath breadfruit trees or beside canoe landings, marking first clearings and founding voyages.

Navigators invoked deities of wind and swell, while ritual plantings of the first breadfruit reaffirmed both genealogical rights and ecological balance.

Canoe construction, launching, and voyaging were sacred acts governed by ritual taboos that linked every island to its mythical origin.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Micronesian communities achieved remarkable ecological equilibrium.

Atoll dwellers sustained themselves on a narrow base of freshwater and soil by integrating arboriculture, lagoon ecology, and social reciprocity.

Islet zoning—separating gardens, wells, canoe yards, and burial sites—optimized space and protected resources.

Food preservation (dried breadfruit, fermented pandanus, smoked fish) buffered households against climate swings.

Inter-island kinship networks allowed redistribution after cyclones or droughts, ensuring collective survival.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 910 BCE, Micronesia had become a maritime commonwealth of small islands woven together by voyaging, arboriculture, and memory.

Its inhabitants had mastered navigation without metal, sustainability without surplus, and connection without empire—a model of balance across one of the planet’s most dispersed archipelagos.

This network of pioneers provided the ecological, technical, and cultural foundation for the monumental navigation and stone-architecture traditions that would later define the Carolines, the Marshalls, and the Micronesian high-island capitals of the medieval centuries.

East Micronesia (2,637 – 910 BCE): First Colonizations — Atoll Settlement, Arboriculture, and Canoe Networks

Geographic & Environmental Context

East Melanesia includes Kiribati (Gilbert Islands), the Marshall Islands (Ralik and Ratak chains), Nauru (uplifted phosphatic limestone island), and Kosrae (high, volcanic island on the eastern Caroline arc).

-

Anchors: Ralik–Ratak pairs in the Marshalls, Gilbert line atolls in Kiribati, Nauru’s uplifted limestone island, and Kosrae high island at the Carolinian margin.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Holocene stability with ENSO-driven interannual variability; drought-sensitive atolls alternated with wet years; Kosrae’s high island buffered extremes.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Austronesian voyagers (Carolinian–Micronesian sphere) established permanent atoll settlements by the late 2nd–early 1st millennium BCE; Kosrae received colonists during the latter half of this epoch or just after.

-

Transported landscapes: coconut, pandanus, breadfruit, and swamp taro (Cyrtosperma; babai in Kiribati) planted; taro pits excavated into the freshwater lens on larger islets.

-

Marine focus: lagoon netting, line fishing, trap fisheries; seasonal turtle capture; reef gleaning.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Outrigger sailing canoes with crab-claw sails; shell/stone adzes; drilled shell fishhooks; fiber cordage.

-

Stick-chart precursors: mnemonic mapping of islands and swells foreshadowed later Marshallese rebbelib and meddo chart traditions.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Ralik ⇄ Ratak shuttle networks tied windward–leeward pairs; Gilbert chain linked north–south islets; Kosrae connected to the eastern Carolines; Nauru functioned as a small provisioning node.

Belief & Symbolism

-

Ancestral land-tenure embedded in house-site stones and tree groves; navigators invoked sea and swell spirits; ritual plantings of first breadfruit honored lineage gods.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Arboriculture mosaics (breadfruit–pandanus–coconut) + taro pits anchored caloric security against drought; islet zoning separated gardens, wells, canoe yards, and burial grounds.

Transition

By 910 BCE, a chain of atoll and high-island settlements spanned East Micronesia, using arboriculture and canoe networks to knit sparse lands into a coherent cultural sea.

West Micronesia (2,637 – 910 BCE): First Colonizations — Marianas Pioneers, Early Palau Settlements, Yap Landfalls

Geographic and Environmental Context

West Micronesia includes the Mariana Islands (Guam, Saipan, Tinian, Rota, and the northern chain), Palau (Babeldaob, Koror, Rock Islands), and Yap (Yap proper and its outer atolls).

-

Anchors: Guam–Saipan–Tinian–Rota (Marianas), Babeldaob–Koror (Palau), Yap proper and nearby atolls.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Holocene stability with ENSO-driven drought/storm interannuals; freshwater lenses critical on limestone islands.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Marianas: among the earliest Remote Oceanic colonizations (c. 1500–1100 BCE). Colonists founded coastal hamlets on leeward flats and embayments; very thin red-slipped pottery (often called “Marianas Red”), shell-tempered, appears alongside shell/bone fishhooks and shell adzes.

-

Palau: initial settlement by late 2nd–early 1st millennium BCE; hamlets on Babeldaob–Koror margins exploited reef–mangrove mosaics and freshwater streams.

-

Yap: first landfalls likely late 2nd–early 1st millennium BCE; small villages near lens-fed wetlands and reef passes.

-

Transported landscapes: coconut, pandanus, breadfruit, and taro took hold; pigs/chickens introduced variably (timing differs by island).

-

Marine focus: lagoon netting and trolling; turtle and pelagic fishing increased; shellfish gleaning ubiquitous.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Outrigger canoes with crab-claw sails; shell/stone adzes; drilled shell fishhooks (including small pelagic forms); fiber cordage from coconut husk; early stone weirs in tidal flats (Palau).

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Marianas chain: inter-island shuttles knit Guam–Saipan–Tinian–Rota;

-

Palau: Rock Islands sheltered canoe routes; Palau exchanged shell adzes and mangrove products with neighbors;

-

Yap: early ties to outer atolls began; voyages westward linked Yap to Caroline pathways.

Belief & Symbolism

-

Ancestral land-tenure embedded in house sites and groves; navigators carried sacred knowledge of stars and swells; shrines at canoe landings marked founding events.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Arboriculture mosaics + lens-managed taro pits buffered drought; distributed islet gardens and reciprocal kin ties hedged cyclones.

Transition

By 910 BCE, Marianas, Palau, and Yap supported permanent settlements linked by canoe circuits — a west Micronesian web of atoll/high-island economies.

Groups from southeastern Asia, primarily speakers of the languages (now) classified as Malayo-Polynesian, begin to spread out to nearby Pacific Islands from about 1500 BCE.

Human habitation in Saipan, the second largest of the Mariana Islands in the western Pacific Ocean, dates from this time.

Micronesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): Atoll Worlds, High-Island Hubs, and the Geometry of the Ocean

Regional Overview

Across the northwestern Pacific, a constellation of small islands and coral atolls—scattered across millions of square kilometers—formed one of humanity’s most intricate maritime environments.

In this early first-millennium epoch, Micronesia was not a single polity but an archipelagic system of localized stability and long-distance communication.

Communities in the east refined life upon fragile atolls through arboriculture, lagoon management, and navigational mastery; those in the west built wet-taro fields, stone fish traps, and canoe networks that tied high islands to far-flung reefs.

Together they composed an oceanic order of balance, reciprocity, and movement: a society not bounded by land but measured by the knowledge of distance.

Geography and Environment

Micronesia arcs between the tropic lines, divided by ecological type into two main subregions.

The eastern chains—Kiribati, the Marshalls, Nauru, and Kosrae—are atoll and low-island worlds: rings of coral enclosing turquoise lagoons, their soils thin and water lenses delicate.

The western arc—the Marianas, Palau, and Yap with its outer atolls—includes both volcanic highlands and uplifted limestone plateaus fringed by rich reefs.

Prevailing trade winds and steady ocean swells unified the region, their seasonal rhythms setting the tempo of planting, sailing, and exchange.

ENSO variability occasionally brought droughts that tested atoll sustainability; yet Micronesian societies turned vulnerability into virtuosity, inventing ecological and social mechanisms for enduring scarcity.

Societies and Political Development

Eastern Micronesia

By the mid-first millennium CE, the atolls of Kiribati and the Marshalls supported well-ordered village polities centered on communal meeting houses (maneaba) and hereditary lineage stewards.

Societies were decentralized but cohesive: social rank derived from kinship, maritime skill, and the ritual redistribution of preserved foods.

On the high, fertile island of Kosrae, valleys supported irrigated taro ponds and emerging sacred kingship (tokosra), a pattern that would blossom into monumental architecture in later centuries.

The atolls, by contrast, prized consensus and survival over hierarchy—each islet functioning as both home and storehouse within a larger archipelagic circuit.

Western Micronesia

In Palau and Yap, taro-swamp engineering and elaborate clan systems underpinned village confederacies.

Chiefly councils managed irrigation, fishing zones, and ceremonial exchange, producing a stable maritime agrarian balance.

Across the Marianas, early latte-house foundations marked a transition toward monumental architecture, while on Yap, ritual tribute networks with the outer atolls—later known as the sawei system—took early shape, binding distant islands in cycles of mutual aid and prestige.

Economy and Exchange

Micronesian economies rested on diversified arboriculture and controlled redundancy.

On atolls, breadfruit, pandanus, and coconut formed the perennial canopy; swamp taro (babai) in excavated pits ensured starch security.

Kosrae and Yap’s river-fed wetlands yielded high crop surpluses, exchanged for reef products and shell valuables.

Across the region, fishing—reef, lagoon, and deep-sea—was both subsistence and ceremony: bait lines, trolling, and weirs harvested the sea’s vertical layers.

Inter-island trade moved preserved breadfruit paste, fine mats, cordage, timber, and shell ornaments.

Shell valuables (e.g., rai stones’ prototypes on Yap, armbands in the Marshalls) were less currency than covenant—tokens of alliance, ritual, and story.

Canoe-building was itself an industry of cooperation: outer islands sent shell tools and fibers to high islands for hull timber and resins, embodying the principle of exchange as survival.

Technology and Material Culture

Canoe architecture reached high refinement.

Outrigger and double-hulled forms combined lightness and resilience; lashings of coconut fiber, sealed with breadfruit sap, produced hulls capable of inter-archipelagic voyages.

The crab-claw sail harnessed both headwind tacking and downwind runs; navigation depended on stars, wave patterns, clouds, and seabird flight.

In the Marshalls, stick charts (rebbelib, meddo) encoded this information as memory maps—graceful wooden geometries representing the curvature of swells and island chains.

Pottery faded from use; woven mats, shell tools, and fiber craft defined daily life.

Maneaba meeting houses and bai (Palau council halls) stood as architectural expressions of cosmology—roof trusses and beams mirroring the celestial order of islands and stars.

Belief and Symbolism

Ancestral spirits governed wind, fish, and fertility.

Each clan traced descent from mythic voyagers or island-creating deities, grounding identity in both ocean and land.

Navigators held sacred rank; their knowledge of stars and swells was protected by ritual observances and initiation.

Ceremonial feasts reaffirmed reciprocity; song and dance rehearsed cosmology and navigation simultaneously.

Across Micronesia, the canoe itself was cosmic model—its hull the world, its mast the axis between sea and sky, its sail the breath of creation.

Adaptation and Resilience

Micronesian survival depended on redundancy, reciprocity, and recordkeeping.

Households spread resources across multiple islets, ensuring that cyclones or droughts on one could be offset by another’s bounty.

Preservation of breadfruit and fish provided long-term stores; exchange networks redistributed wealth and food after storms.

Social protocols of hospitality turned mobility into insurance: a guest was never a stranger but a partner in the continuum of voyaging kin.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 819 CE, Micronesia had achieved a stable and sophisticated equilibrium between ecology and exchange.

Its two spheres—East Micronesia’s atoll commons and West Micronesia’s high-island hierarchies—formed a balanced duality: one democratic and dispersed, the other structured and monumental.

Together they created a resilient maritime civilization, every island both node and compass point in a larger design.

This early system anticipated the monumental age to come: the stone cities of Lelu and Nan Madol, the latte pillars of the Marianas, and the full flowering of the sawei network on Yap.

Yet even in its beginnings, Micronesia demonstrates why regional history must be read through its subregions: the ocean itself demanded variety, and the archipelago’s unity lay not in uniformity but in the mathematics of difference — a geometry of survival traced upon the sea.

East Micronesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): Post-Settlement Flourishing — Maneaba Houses, Stick-Chart Knowledge, and High-Island Specialization

Geographic & Environmental Context

East Melanesia includes Kiribati (Gilbert Islands), the Marshall Islands (Ralik and Ratak chains), Nauru (uplifted phosphatic limestone island), and Kosrae (high, volcanic island on the eastern Caroline arc).

-

Anchors: Ralik–Ratak villages (Marshall Islands), Gilbert atoll districts (Kiribati), Nauru’s plateau villages, and Kosrae’s stream-fed valleys and sheltered reef.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

First-millennium oscillations increased ENSO drought risk on equatorial atolls; Kosrae’s streams and orographic rains buffered shortages; intra-chain redistribution grew in importance.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Atolls: intensified taro-pit agriculture; seasonal breadfruit surplus dried into bwiro (fermented paste); coconut toddy and pandanus paste diversified diet.

-

Kosrae: wet-field taro systems developed in stream valleys; basalt adze workshops began to supply regional demand.

-

Nauru: small lens-fed gardens and reef fisheries sustained modest populations.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Canoe fleets standardized (outriggers with crab-claw sails); refined voyaging guilds transmitted star compasses and swell-reading;

-

Stick charts crystallized into Marshallese rebbelib (overall) and meddo (localized) mnemonic maps; shell and bone fishhooks diversified; fine fiber mats and sennit cordage proliferated.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Regular Ralik–Ratak tribute and reciprocity circuits; Gilbert chain north–south canoe lanes; Kosrae served as a high-island hub for freshwater, timber, and basalt adzes; San Andrés/Caroline sphere to the west remained an external partner.

Belief & Symbolism

-

Maneaba (Kiribati meeting house) traditions formed as political–ritual centers; navigators held sacred knowledge and ritual obligations; ancestor shrines guarded wells and groves.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Distributed islet zoning and inter-atoll reciprocity buffered drought and storm damage; food preservation(dried breadfruit, pandanus paste, smoked fish) extended security; canoe logistics ensured rapid relief within chains.

Transition

By 819 CE, East Micronesia had matured into a lattice of atoll chiefdoms and a high-island node (Kosrae), bound by canoe routes, maneaba institutions, and stick-chart navigation — a resilient oceanic system poised for the monumental phase (e.g., Lelu) of the later medieval centuries covered in our 1108–1251 and 1252–1395 narratives.

West Micronesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): Post-Settlement Flourishing — Canoe Logistics, Village Systems, and Monumental Trajectories

Geographic & Environmental Context

West Micronesia includes the Mariana Islands (Guam, Saipan, Tinian, Rota, and the northern chain), Palau (Babeldaob, Koror, Rock Islands), and Yap (Yap proper and its outer atolls).

-

Anchors: Guam–Saipan–Tinian–Rota villages; Babeldaob–Koror (Palau) with the Rock Islands; Yap proper with outer-atoll satellites (Ulithi–Woleai).

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

First-millennium oscillations increased drought risk on limestone islands; Palau’s volcanic catchments and Yap’s wetlands buffered dryness; redistribution voyages grew central.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Marianas: coastal settlements expanded; by the late first millennium CE the foundations for megalithic latte architecture were forming (full florescence mostly after 800–900 CE).

-

Palau: irrigated taro-swamp systems (Babeldaob) matured; mangrove/reef management intensified; village compounds took characteristic forms.

-

Yap: wet-field taro and reef estates knit villages; outer-atoll ties (Ulithi, Woleai) supplied shell valuables, while Yap supplied timber and stone.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Standardized outriggers with robust sails; stone fish weirs and tidal traps; shell adzes and basalt imports; fine fiber mats.

-

In Marianas, pottery traditions simplified; shell/bone hooks specialized for pelagics; groundwork for latte house foundations (megalithic caps and pillars) set late in the period.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Regular canoe convoys circulated food, timber, and tools across each archipelago; Yap–outer atoll ties deepened; Palau served as a high-island hub for mangrove/timber and lagoon products.

Belief & Symbolism

-

Navigator guilds held sacred star-path knowledge; founding shrines at passes/landings; ancestor stones and canoe-house rituals sanctified tenure.

-

The social prestige of long-distance voyaging rose; ritual feasts sealed alliances.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Distributed islet zoning, taro-pit agriculture, arboriculture, and reciprocal exchange buffered ENSO droughts and cyclones; canoe logistics enabled rapid inter-village relief.

Transition

By 819 CE, West Micronesia was a lattice of settled canoe societies: Marianas moving toward the latte era, Palau with mature taro-swamp engineering, and Yap orchestrating high-island/outer-atoll exchange — all precursors to the monumental and tribute systems described in our later medieval entries.

East Micronesia (820–1971 CE): Colonization, Resistance, and Independence

Political and Military Developments

Indigenous Governance and Societal Structures

Between 820 and 1800 CE, indigenous East Micronesian societies, including those in Kosrae, the Marshall Islands, Kiribati, and Nauru, continued developing complex social structures and political systems based on clan leadership, community consensus, and strategic alliances.

European Exploration and Colonization

European exploration significantly impacted East Micronesia beginning in the 16th century, but substantial colonization efforts intensified in the late 19th century. Germany established colonial control over the Marshall Islands and Nauru in 1886 and 1888, respectively. Kiribati fell under British protection in 1892, while Kosrae became part of German Micronesia until it transferred to Japanese administration post-World War I.

Japanese and American Administration

Post-World War I, Japan administered the region under a League of Nations mandate until its defeat in World War II. Afterward, the United States assumed administrative authority over the Marshall Islands and Kosrae under the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. Nauru became jointly administered by Australia, New Zealand, and Britain, while Kiribati remained under British colonial rule.

Movement Toward Independence

Throughout the 20th century, nationalist movements and demands for self-governance intensified. By the late 1960s, significant strides toward independence occurred, culminating in eventual sovereignty for many island states in subsequent years.

Economic and Technological Developments

Economic Transformation under Colonial Rule

Colonial rule introduced significant economic transformations, including the commercialization of copra production, phosphate mining in Nauru beginning in 1906, and infrastructure improvements aimed at facilitating resource extraction and colonial governance.

Technological and Infrastructure Advances

Colonial powers introduced modern infrastructure such as transportation networks, telecommunications, and improved maritime facilities. These developments fundamentally reshaped local economies, social structures, and everyday life in East Micronesia.

Cultural and Artistic Developments

Cultural Preservation and Adaptation

Despite colonial pressures, East Micronesian communities preserved many traditional cultural practices, including oral histories, navigational traditions, and communal rituals. Artistic expressions blended indigenous and colonial influences, creating dynamic cultural landscapes.

Revival and Assertion of Indigenous Culture

The 20th century saw concerted efforts to revive and assert indigenous cultural identities, particularly in response to external influences and increasing calls for independence and autonomy.

Social and Religious Developments

Impact of Christianity

Missionaries significantly impacted religious and social structures throughout East Micronesia. Christianity, predominantly Protestantism and Catholicism, became widely adopted, integrating with traditional belief systems and influencing community practices and societal norms.

Social Transformation

Colonial administration introduced Western education, legal frameworks, and governance models, dramatically reshaping local societies. However, traditional kinship systems, clan structures, and communal decision-making practices persisted as core societal foundations.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The period from 820 to 1971 CE marked transformative developments in East Micronesia, characterized by colonial encounters, economic changes, cultural adaptation, and the drive toward self-determination. These centuries profoundly influenced regional identities, social structures, and economic foundations, setting the stage for post-colonial nation-building and ongoing regional dynamics.

Micronesia (820 – 963 CE): Atoll Adaptations, Sacred Kingship, and the Ocean of Exchange

Geographic and Environmental Context

Micronesia in this age stretched across thousands of kilometers of the western Pacific, a constellation of coral atolls and volcanic peaks lying between the equator and the tropic lines.

It embraced two broad zones:

-

West Micronesia — the Mariana Islands, Yap, Palau, Chuuk, and their surrounding atolls — high volcanic islands and lagoon systems forming the core of early political hierarchies.

-

East Micronesia — the Marshall Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, and the high island of Kosrae — a vast field of atoll chains and single peaks where communities perfected arboriculture, water-lens management, and long-range navigation.

Across both regions, communities transformed fragile maritime environments into stable cultural seascapes, balancing horticulture, reef fisheries, and ritualized exchange.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The centuries between 820 and 963 CE brought generally warm, stable tropical conditions, though subject to ENSO-driven droughts and occasional typhoons.

-

Atolls endured episodic stress on water lenses and breadfruit groves, mitigated by arboriculture and preserved food stores.

-

High islands such as Kosrae, Yap, and Palau buffered shortages with orographic rainfall and permanent streams.

-

Across the archipelagos, ocean currents and trade-wind predictability allowed continuous voyaging, even during lean years.

Micronesia’s ecological equilibrium rested on the rhythm of sea, wind, and communal preparedness.

Societies and Political Developments

West Micronesia: Prestige Centers and Voyaging Networks

-

Yap emerged as a ritual and economic magnet, its chiefs (later gatchaper) forging hierarchical alliances with outer atolls through early forms of the sawei system. Outer islands provided preserved breadfruit, mats, and shells, receiving timber, turmeric, and prestige stones in return.

-

Chuuk Lagoon organized dense volcanic-island chiefdoms under clan leadership, combining horticulture with lagoon fishing and fortified refuges for defense.

-

Palau’s councils of chiefs governed taro-swamp agriculture and lagoon tenure, resolving disputes through ritual and warfare.

-

In the Marianas, the appearance of latte-stone house foundations marked rising chiefly hierarchy; ancestral lines (maga’låhi) consolidated authority through megalithic architecture.

-

The outer Carolinian atolls maintained autonomy but oriented ritual and tribute ties toward Yap’s prestige sphere.

East Micronesia: Atoll Confederacies and Sacred Kingship

-

In the Marshalls, a tripartite social structure of iroij (paramounts), alab (land stewards), and rijerbal (workers) governed atoll society through lineage and reef tenure.

-

Kiribati (Gilbert Islands) centered life in the maneaba, the communal meeting house where elders mediated access to land, water, and fishing grounds.

-

Nauru sustained small clan communities based on reef and nearshore fisheries, supplementing limited gardens with exchange to passing canoes.

-

On the volcanic high island of Kosrae, reliable water and forest surpluses fostered the first stirrings of centralized kingship (tokosra). Ritual leaders presided over first-fruit ceremonies and temple feasts, precursors to the monumental Lelu court of later centuries.

Economy and Trade

Micronesia’s economy revolved around diversity, storage, and exchange.

-

Horticulture and arboriculture: taro (wet and dry), yam, breadfruit, coconut, and pandanus formed the dietary backbone; swamp-taro pits (babai) safeguarded food through drought.

-

Fisheries: lagoon and deep-sea fishing, shellfish collecting, and turtle hunting ensured protein security.

-

Preservation and storage: fermented breadfruit, dried fish, and pandanus paste sustained communities through cyclone and El Niño cycles.

-

Inter-island exchange:

-

Atoll goods (shells, mats, sennit cordage, dried foods) moved to high islands for timber and stone.

-

Yap’s sawei and Kosrae’s trade sphere bound outer islands to ritual centers.

-

Voyaging networks interlaced West and East Micronesia, extending from the Philippines to the Marshalls.

-

Subsistence and Technology

-

Water management: lined and composted taro pits, carefully placed wells, and grove mulching protected fragile freshwater lenses.

-

Canoe-building: breadfruit and mahogany hulls, lashed with coconut fiber; outrigger or double-hulled designs with crab-claw or triangular sails; atoll canoes were lightweight and swift, high-island craft sturdy for cargo.

-

Navigation: wayfinding through star compasses, ocean swells, seabird routes, and in the Marshalls, stick charts (rebbelib, meddo) modeling wave interactions.

-

Architecture: maneaba and bai (Palau meeting houses) served as both civic and ritual centers; latte-stone platforms in the Marianas elevated houses and shrines above coastal floods.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Sawei routes radiated from Yap to Ulithi, Woleai, Lamotrek, and Satawal, structuring periodic tribute voyages.

-

Ralik–Ratak channels joined Marshall atolls into a coherent political ecology.

-

Kosrae served as an eastern hub linking high-island and atoll economies, dispatching food and craft goods in exchange for shells and ornaments.

-

Kiribati and Nauru tied into broader Gilbert–Marshall sailing circuits; Palau and Chuuk reached westward toward the Philippines and eastward toward the Carolines.

These routes made Micronesia an oceanic commons, sustained by obligation, reciprocity, and shared wayfinding knowledge.

Belief and Symbolism

Micronesian spirituality merged ancestral power, sea cosmology, and navigational ritual.

-

In Kiribati, the maneaba embodied both civic governance and sacred genealogy.

-

In the Marshalls, chiefs traced descent from founding navigators and land-spirit ancestors.

-

Kosrae’s early kingship fused divine sanction with agricultural fertility; rituals of first-fruits and canoe consecration unified people and place.

-

Across the Carolines, voyaging chants preserved sacred geography; in Palau, monumental bai meeting houses displayed carved mythic motifs connecting taro swamps to the spirit world.

-

Yap’s stone shrines and Marianas’ latte stones anchored ancestry in enduring materials.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Multi-island subsistence portfolios buffered risk: high islands exported timber and taro; atolls supplied dried fish, coconut, and mats.

-

Preservation and storage mitigated ENSO droughts.

-

Voyaging alliances redistributed food after cyclones or crop loss.

-

Ritual redistribution through tribute and feasting balanced wealth and prestige, reinforcing ecological cooperation.

-

Tenure flexibility—rotating land and reef use—allowed renewal of fragile environments.

Micronesian resilience rested on mobility, reciprocity, and reverence for the sea.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, Micronesia had become a maritime commonwealth of integrated yet diverse societies:

-

Yap commanded a radiating prestige sphere through early sawei tribute.

-

Kosrae rose as a sacred polity presaging later monumental rule.

-

Marianas, Palau, and Chuuk established enduring architectural and political forms.

-

Kiribati and the Marshalls refined atoll arboriculture and navigation into an art of survival.

Together, these islands forged one of humanity’s most resilient oceanic civilizations—a world where star paths, breadfruit groves, and reef channels formed the arteries of life and law, linking scattered atolls into a single, voyaging society.

East Micronesia (820 – 963 CE): Atoll Adaptations, Kosraean Centralization, and Ocean-Wayfinding

Geographic and Environmental Context

East Micronesia includes Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, and Kosrae.

-

Kiribati (Gilbert Islands) and the Marshall Islands (two parallel chains, Ralik and Ratak) are mostly low coral atolls with thin soils, freshwater lenses, and extensive lagoons.

-

Nauru is an uplifted limestone island with limited arable pockets and rich nearshore fisheries.

-

Kosrae is a single high volcanic island with steep forested slopes, perennial streams, and a protective fringing reef—an ecological outlier that offered surpluses and political gravity.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Equatorial trade winds and a warm maritime regime prevailed.

-

ENSO variability produced periodic droughts that stressed atoll agriculture and water lenses, while typhoons occasionally damaged breadfruit groves and canoe fleets.

-

Kosrae’s orographic rainfall buffered shortages that hit the atolls harder.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Kiribati: kin-based lineages organized village life around the community meeting house (maneaba), with elders arbitrating land-use on narrow motu and rights to taro pits, groves, and reef sectors.

-

Marshall Islands: hierarchical but distributed authority—iroij (paramount chiefs), alab (lineage land stewards), and rijerbal (commoner workers)—managed land, labor, and lagoon tenure across Ralik–Ratak atolls.

-

Nauru: small, clan-centered communities balanced nearshore fishing, garden plots, and reef gleaning with exchange to passing canoes.

-

Kosrae: fertile valleys and secure water allowed the coalescence of sacred kingship (early forms of the tokosra), with centralized ritual leadership beginning to outscale atoll chiefdoms. The seeds of later Lelu court development were sown in this period, even if its monumental stone city would flourish later.

Economy and Trade

-

Atoll arboriculture: coconut, pandanus, and breadfruit formed staple canopies; swamp taro in excavated pits (babai) provided drought insurance.

-

Fishing & reef harvests: lagoon netting, trolling, weirs, and shellfish gathering produced steady protein; fermented breadfruit pastes and cured fish created cyclone/drought stores.

-

Inter-island exchange: preserved foods, fine mats, shell ornaments, high-quality cordage (sennit), and canoe parts circulated between atolls; Kosrae exported taro, breadfruit, timber, and craft goods in return for shells and specialized items from the low isles.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Water management: careful well-siting and grove mulching protected fragile freshwater lenses; taro pits were lined and composted to buffer salinity.

-

Canoe-building: outrigger sailing canoes (single and double) lashed with sennit; breadfruit and other hardwoods provided hulls on Kosrae, while atolls specialized in light, swift craft.

-

Navigation: wayfinding relied on star paths, swell patterns, seabird behavior, and (in the Marshalls) stick charts (rebbelib, meddo) mapping wave interference and island positions.

-

Food preservation: smoking/drying of fish and fermented breadfruit pastes stabilized calories across lean seasons.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Ralik–Ratak voyaging knit Marshall atolls into a shared political ecology; canoes moved seasonally with prevailing trades.

-

Gilbertian (Kiribati) circuits linked northern and southern atolls, coordinating marriage alliances and mutual-aid exchanges during drought.

-

Kosrae sat at the eastern Carolinian edge, drawing in visitors from neighboring high islands and dispatching surplus to surrounding low isles.

-

Nauru interacted opportunistically with passing Marshallese and Gilbertese vessels.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Sea and wind deities and ancestor spirits governed success in fishing, sailing, and grove fertility; ritual specialists mediated between community and ocean/weather powers.

-

In Kiribati, the maneaba embodied communal authority and sacred history; in the Marshalls, chiefly lines traced prestige to founding navigators and sacred lands.

-

Kosrae developed sacral kingship idioms—ritual first-fruits, temple feasts, and court specialists—that prefigured later urban ceremonial life.

-

Canoe consecrations and navigation chants embedded cosmology in everyday voyaging.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Risk-spreading portfolios—breadfruit, coconut, babai, reef fish, pelagic catches—reduced dependence on a single resource.

-

Preservation technologies (fermented breadfruit, dried fish) and storm-resistant arboriculture buffered shocks.

-

Mutual-aid pacts and inter-atoll voyaging redistributed food during droughts; Kosrae’s surpluses served as a regional safety valve.

-

Flexible land/reef tenure systems allowed households to rotate use, rest fragile patches, and share labor for pit excavation and canoe repair.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, East Micronesia had stabilized a resilient atoll–high island system:

-

Atolls in Kiribati and the Marshalls perfected water-lens gardening, reef tenure, and wayfinding, sustaining dense communities on scant soils.

-

Kosrae began to differentiate as a centralized sacred polity, a trend that would culminate in the Lelu stone court in later centuries.

-

Nauru occupied a modest but strategic niche, linking eastern and western atoll chains.

Together, these societies built a voyaging commons and subsistence toolkit that would carry East Micronesia through climatic swings and into a period of monumentalization and intensified exchange after 964 CE.