Maritime East Asia (1852–1863 CE): Reforms, Resistance, and Rebellion

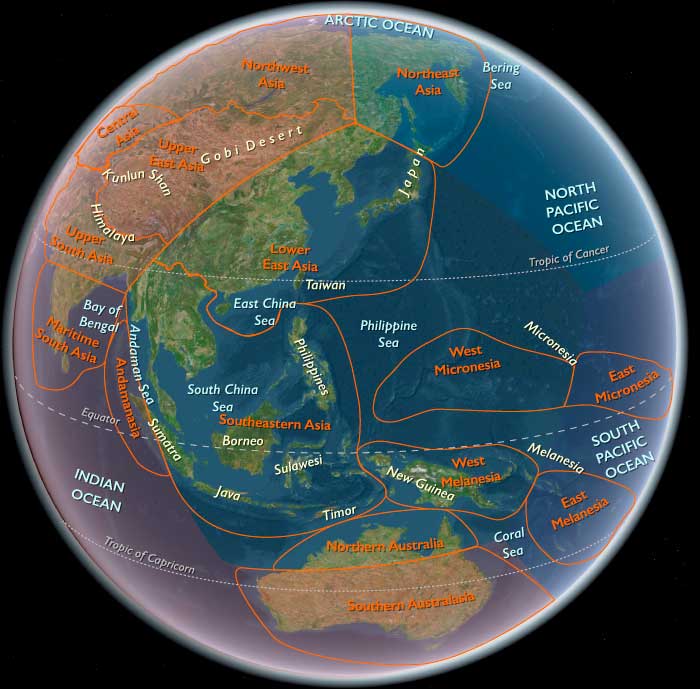

Between 1852 and 1863 CE, Maritime East Asia—covering lower Primorsky Krai, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese Archipelago south of northern Hokkaido, Taiwan, and southern, central, and northeastern China—faces continued Western pressure, internal rebellions, and significant political transformations, reshaping regional power structures and paving the way for dramatic changes in the decades ahead.

China: The Taiping Rebellion and Qing Decline

China remains embroiled in the devastating Taiping Rebellion, led by Hong Xiuquan, who had declared the establishment of the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace in 1851. The rebellion, blending Protestant ideals with anti-Manchu fervor, captures key cities such as Nanjing, asserting radical social reforms, communal land ownership, and strict moral codes. However, the rebellion’s radical ideology alienates the Confucian scholar-gentry, and internal feuds undermine its effectiveness.

In response, the Qing dynasty entrusts scholar-official Zeng Guofan with suppressing the Taiping. Zeng’s innovative "Hunan Army," funded by local taxes and led by scholar-generals, significantly strengthens the Qing's military capabilities. Despite ongoing battles against simultaneous uprisings like the Nien and Muslim Rebellions, Zeng’s actions mark the rise of a new Han Chinese elite and further erode Qing central authority.

Qing Efforts at Modernization

Facing internal turmoil and external threats, Qing China initiates cautious modernization efforts under forward-thinking Han officials. They adopt Western science and diplomatic practices, open specialized schools in urban centers, and establish arsenals, factories, and shipyards modeled after Western methods. This practical approach, however, remains secondary to the dynasty's primary goal of preserving traditional structures.

The Tongzhi Restoration (1862–1874), led by Empress Dowager Cixi, represents this cautious modernizing impulse, seeking practical solutions within traditional frameworks. Although it partially stabilizes the regime, it falls short of the comprehensive reforms needed to effectively meet external threats and internal challenges.

Japan: The Bakufu’s Response to Western Pressure

In Japan, the Tokugawa shogunate continues to grapple with the impact of Western pressure, intensified after Commodore Matthew C. Perry forces Japan open in 1853–54. The bakufu under Abe Masahiro initially attempts a cautious balance between accommodation and military preparedness, establishing naval training with Dutch instructors and translating Western texts.

However, internal divisions deepen. Tokugawa Nariaki, a vocal advocate for imperial restoration and opponent of foreign influence, represents growing nationalist and anti-Western sentiment. After the death of the shogun without a clear heir, the political struggle intensifies, eventually leading to the arrest of Nariaki and his favored candidate, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, and the execution of prominent nationalist intellectual Yoshida Shoin. The bakufu's concessions to foreign powers—including extraterritorial rights and increased trade access—further erode its credibility and authority, fueling domestic unrest.

Joseon Korea: Deepened Isolation and Resistance

Joseon Korea, observing the aggressive Western actions in China and Japan’s forced opening, doubles down on isolation. Hostility toward Western influences intensifies, especially against Catholicism, leading to harsh persecutions. The government firmly rejects foreign trade overtures, further isolating Korea from international developments. This reactionary stance exacerbates internal tensions and economic decline, laying the foundation for future internal uprisings and external conflicts.

Legacy of the Era: Resistance, Reform, and Continued Instability

The period from 1852 to 1863 CE leaves Maritime East Asia marked by ongoing resistance to Western pressures, uneven and cautious reforms, and deep internal instability. China struggles to quell devastating rebellions and preserve its weakening dynasty, Japan faces rising nationalist opposition to the increasingly compromised shogunate, and Korea remains rigidly closed, storing tensions that will soon erupt into significant upheaval. These developments profoundly shape the trajectory of the region, setting the stage for major transformations in the late nineteenth century.