Syngman Rhee

1st President of South Korea

Years: 1875 - 1965

Syngman Rhee or Yi Seung-man (March 26, 1875 – July 19, 1965) was the first president of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea as well as the first president of South Korea.

When the way for the independence movement in the Japanese colonial period and the comments stand apart, he announces the domestic situation to foreign countries.

His latter three-term presidency (August 1948 to April 1960) is strongly affected by Cold War tensions on the Korean peninsula.

Rhee is regarded as an anti-Communist and a strongman, and he leads South Korea through the Korean War.

His presidency ends in resignation following popular protests against a disputed election.

He dies in exile in Honolulu, Hawaii.

He is a 16th descendant of Grand Prince Yangnyeong.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 5 events out of 5 total

Maritime East Asia (1828–1971 CE): Dynastic Collapse, Imperial Encounters, and Industrial Revolutions

Geography & Environmental Context

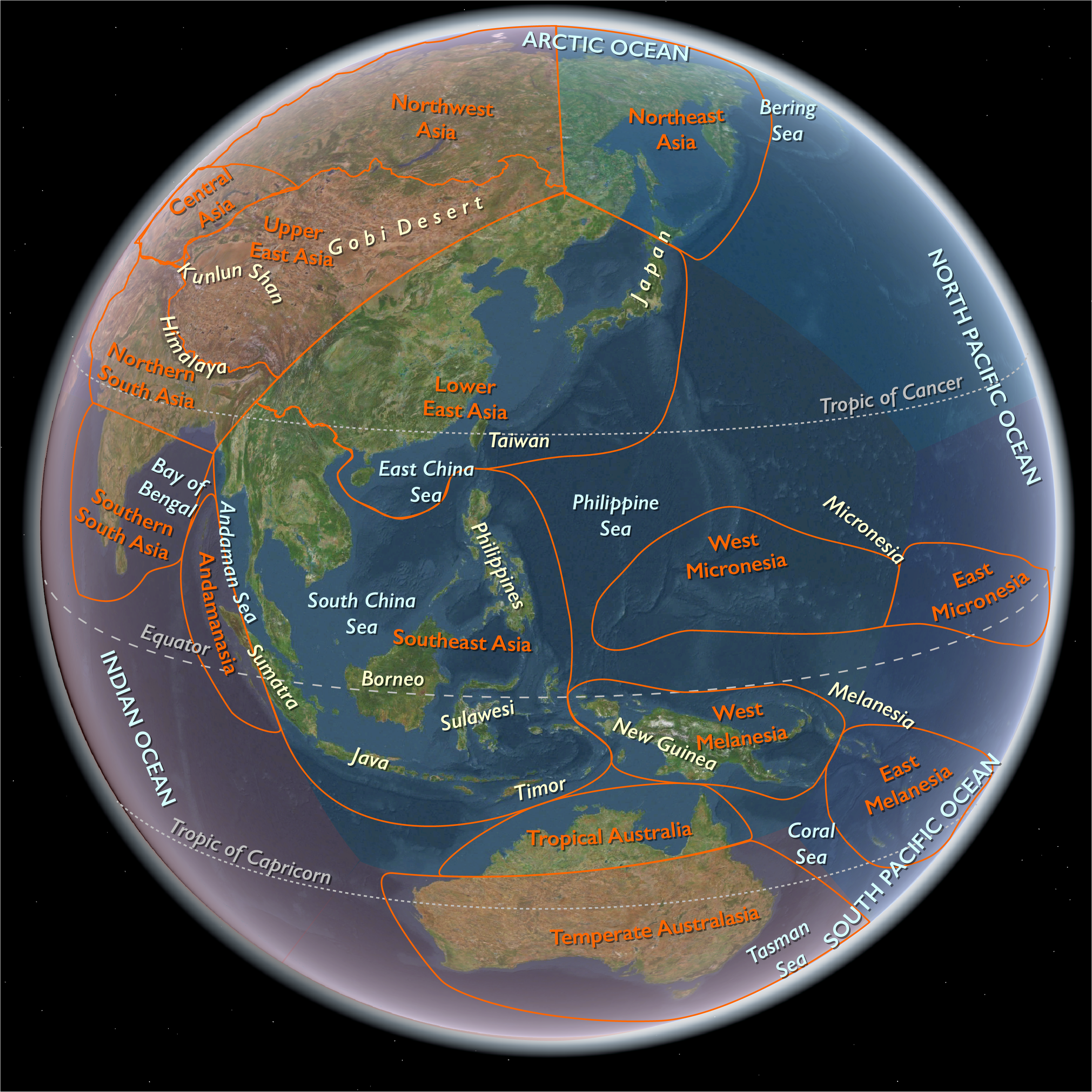

Maritime East Asia encompasses southern and eastern China (Yunnan, Guangxi, Guizhou, Sichuan Basin, Chongqing, Hunan, Hubei, Henan, Shanxi, Hebei, Beijing, Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Shandong, Liaoning, Jilin, southern Heilongjiang), Taiwan, the Korean Peninsula, southern Primorsky Krai, and the Japanese islands of Kyushu, Shikoku, Honshu, and southwestern Hokkaidō, plus the Ryukyu and Izu island chains. Anchors include the Yangtze and Yellow River basins, the Sichuan Basin, the Pearl River Delta, the Korean mountains and Han River valley, and the Japanese archipelago stretching into the Pacific.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The subregion’s monsoonal regime brought alternating floods and droughts. China’s Yellow River repeatedly shifted course (notably floods of 1855, 1931), devastating farmlands. Famines struck northern China and Korea in the 19th century; deforestation in uplands worsened soil erosion. Typhoons regularly battered Taiwan, Fujian, and the Ryukyu chain. Industrial urbanization in Japan, Korea, and later coastal China introduced pollution and new ecological strains by the mid-20th century.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

China: Rice dominated the south (Yangtze, Pearl deltas); wheat, millet, and sorghum fed the north. Tea, silk, and cotton underpinned commerce. Urban hubs like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Wuhan, and Chongqing grew rapidly.

-

Korea: Rice paddies in the south, millet and barley in the north; fishing villages dotted the coasts. Seoul (Hanyang) expanded modestly until the late 19th century, then became a colonial capital under Japan.

-

Japan: Rice agriculture was the base, but from the Meiji era (1868), industrialization transformed Osaka, Tokyo, and Yokohama into manufacturing and commercial centers.

-

Taiwan: Rice and sugar cultivation thrived; under Japanese colonial rule (1895–1945), plantations and infrastructure expanded.

-

Primorsky Krai: Fishing, forestry, and Russian settler agriculture integrated this fringe into both East Asian and Siberian networks.

Technology & Material Culture

-

19th century China: Weaving, porcelain, and handicrafts persisted; steamships, telegraphs, and railways entered through treaty ports.

-

Japan: The Meiji era imported Western technology; shipyards, railways, and modern factories reshaped cities. Postwar, Japan pioneered electronics and automobiles.

-

Korea: Under Japanese rule (1910–1945), railways, mines, and ports were developed; after 1945, the peninsula divided—North Korea industrialized under Soviet aid; South Korea struggled with war but began post-1960s export-driven growth.

-

Taiwan: Railways, irrigation, and port works under Japan; post-1949 Nationalist rule built industry with American support.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Maritime hubs: Shanghai, Guangzhou, Nagasaki, and Busan tied the region into global shipping.

-

Railroads: Transcontinental Russian lines reached Primorsky; Japan built dense domestic networks; China’s first railways (1870s onward) expanded in treaty-port regions.

-

Migration: Millions of Chinese emigrated to Southeast Asia and the Americas; Japanese settlers moved into Korea and Taiwan under empire.

-

War corridors: From the Opium Wars (1839–42) to the Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), Pacific War (1941–45), and the Korean War (1950–53), armies moved repeatedly across the subregion.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

China: The late Qing saw the Taiping and Boxer upheavals; Confucian traditions contended with Christian missions and modern reform. Republican-era intellectuals (May Fourth Movement, 1919) fostered new literature and nationalism.

-

Japan: The Meiji Restoration cultivated Shinto nationalism and Western-style arts; post-1945, pacifist democracy blended tradition with global modernism.

-

Korea: Confucian yangban culture dominated until colonization; Korean nationalism and literature grew under Japanese censorship; division after 1945 entrenched contrasting socialist and capitalist cultures.

-

Taiwan: Indigenous Austronesian traditions persisted alongside Chinese settler practices; Japanese colonial architecture and education left a lasting imprint.

-

Pan-Asian encounters: Buddhism, Confucianism, Shinto, Christianity, and modern ideologies all competed for influence.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Flood control: Dikes and canals in China remained vital; 20th-century hydropower projects (Three Gorges precursors, 1950s–60s) began reshaping rivers.

-

Agrarian diversification: Potatoes, maize, and sweet potatoes spread, buffering famine in parts of China and Korea.

-

Urban resilience: Post-1945 reconstruction rebuilt Tokyo, Seoul, and Shanghai after wartime devastation.

-

Industrial adaptation: Japan rebuilt rapidly after 1945 into an export powerhouse, while China’s collectivization and Great Leap Forward (1958–62) caused famine but later stabilized under gradual reforms.

Political & Military Shocks

-

China:

-

Opium Wars (1839–42, 1856–60) opened treaty ports.

-

Taiping (1850–64) and Boxer (1899–1901) Rebellions shook Qing rule.

-

Fall of Qing (1911), Republic of China, and civil war (1920s–1949).

-

PRC founded 1949; Great Leap Forward (1958–62) and Cultural Revolution (1966–76) disrupted society.

-

-

Japan:

-

Meiji Restoration (1868); rapid modernization and empire-building.

-

Wars with China (1894–95), Russia (1904–05), and WWII (1941–45).

-

Defeat in 1945; U.S. occupation (1945–52) imposed democratic reforms.

-

-

Korea:

-

Annexed by Japan (1910–45); liberation after WWII.

-

Division (1945) and Korean War (1950–53) entrenched North/South split.

-

-

Taiwan:

-

Japanese colony (1895–1945).

-

Became base of Republic of China (Kuomintang) after 1949.

-

-

Primorsky Krai: Incorporated into Russian Empire (mid-19th c.); fortified as Soviet Far Eastern frontier in the Cold War.

Transition

Between 1828 and 1971, Maritime East Asia moved from dynastic decline and semi-colonial pressures to industrial revolutions, world wars, and ideological division. Qing China collapsed into republican and then communist rule; Japan transformed into both an empire and then a postwar economic powerhouse; Korea endured colonization, liberation, and Cold War partition; Taiwan became the stronghold of the Kuomintang. By 1971, the subregion was a Cold War flashpoint—with China’s UN seat transferring to the PRC, Japan rising as a global economic power, and the Korean peninsula divided—yet also a region of cultural dynamism and resilience rooted in centuries-old agrarian and urban traditions.

Maritime East Asia (1888–1899 CE): Imperial Expansion, Reform Efforts, and Emerging National Identities

Between 1888 and 1899 CE, Maritime East Asia—including lower Primorsky Krai, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese Archipelago south of northern Hokkaido, Taiwan, and southern, central, and northeastern China—experiences profound imperial expansion, dynamic reform movements, and the crystallization of national identities. The period sees intensified foreign incursions and heightened internal pressures, significantly shaping each region's political landscape.

Korea: Turmoil, Reform Movements, and Foreign Domination

Following Korea's forced opening in the previous decade, the peninsula faces increased international attention and interference. Japan solidifies its influence through the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), triggered by the Donghak Rebellion—an uprising fueled by religious fervor and widespread dissatisfaction with governmental corruption. Korean attempts to suppress the rebellion lead to Chinese intervention, providing Japan a pretext to enter militarily and decisively defeat China. Through the Treaty of Shimonoseki (1895), Japan gains hegemony over Korea, imposing sweeping domestic reforms to quell further unrest, including abolishing class distinctions, emancipating slaves, and dismantling the rigid civil service examination system.

Meanwhile, nationalist sentiment and calls for reform flourish, notably through the efforts of So Chae-p'il. Returning from exile in the United States in 1896, So promotes modernization and independence from foreign control. He establishes the influential newspaper Tongnip simmun (The Independent) and organizes the Independence Club, advocating Western-style democratic reforms. Despite initial success and significant popular support, conservative opposition violently suppresses these movements, forcing So back into exile and imprisoning many activists, including future leader Syngman Rhee.

Japan: Constitutional Government and National Strength

Japan's Meiji leaders successfully consolidate their political system with the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution (1889), based largely on the Prussian model. This constitution maintains centralized imperial authority while allowing limited representative governance through an elected Diet. The first national election in 1890 signals the burgeoning strength of political parties, notably the Liberal Party (Jiyuto) and the Constitutional Progressive Party (Rikken Kaishinto), which increasingly challenge governmental policies.

Despite these democratic features, real political power remains concentrated among the influential oligarchy known as the genro (elder statesmen), who continue to govern behind the scenes. Prominent leaders such as Ito Hirobumi and Yamagata Aritomo shape Japan's domestic and foreign policies, emphasizing rapid industrialization, military modernization, and active diplomacy. Japan's defeat of China in the First Sino-Japanese War cements its emergence as a significant regional power, further expanding its empire by acquiring Taiwan and the Penghu Islands.

China: Intensifying Foreign Influence and Failed Reform

China under the declining Qing dynasty faces escalating foreign encroachment and internal instability. The First Sino-Japanese War exacerbates China's vulnerabilities, forcing substantial territorial concessions, including ceding Taiwan to Japan and granting increased foreign privileges. In response to these mounting crises, Emperor Guangxu initiates the ambitious Hundred Days' Reform (1898), aiming for sweeping institutional and ideological changes inspired by Japan’s successful modernization.

However, conservative opposition led by the powerful Empress Dowager Cixi swiftly reverses these efforts. With military backing, she suppresses reformist leaders and seizes control in a coup, rescinding the progressive edicts and severely punishing reform advocates. This reactionary turn deepens China's internal divisions, accelerating the dynasty’s decline and leaving the country increasingly vulnerable to external manipulation.

Taiwan: Resistance and Integration into Japan

Taiwan, newly acquired by Japan following the Treaty of Shimonoseki, becomes a focal point of resistance against foreign domination. A short-lived attempt to establish the independent Republic of Formosa in 1895 is quickly quelled by Japanese military forces. Persistent guerrilla resistance continues intermittently until around 1902, causing significant casualties and underscoring Taiwanese resentment against foreign rule. Nonetheless, Japan begins comprehensive modernization and infrastructure projects on the island, including the construction of railways, firmly integrating Taiwan into its growing empire.

Legacy of the Era: Emerging Nationalism and Imperial Ambitions

Between 1888 and 1899 CE, Maritime East Asia experiences dramatic imperial expansion, complex internal reforms, and heightened nationalist sentiments. Japan emerges as a dominant regional power, wielding considerable influence over neighboring Korea and Taiwan while shaping modern governmental structures domestically. China’s brief reform efforts highlight ongoing internal struggles and vulnerabilities that hasten the Qing dynasty's downfall. Korea’s independence movements, though suppressed, lay foundations for future resistance and national identity. Collectively, these transformations underscore deepening national consciousness and imperial ambitions, significantly influencing the geopolitical dynamics of East Asia into the twentieth century.

A massive campaign is meanwhile launched in Korea, under the leadership of So Chae-p'il, who had exiled himself to the United States after participating in an unsuccessful palace coup in 1884, to advocate Korean independence from foreign influence and controls.

As well as supporting Korean independence, So also advocates reform in Korea's politics and customs in line with Western practices.

Upon his return to Korea in 1896, So publishes Tongnip simmun (The Independent), the first newspaper to use the hangul writing system and the vernacular language, which attracts an ever-growing audience.

He also organizes the Independence Club to introduce Korea's elite to Western ideas and practices.

Under his impetus and the influence of education provided by Protestant mission schools, hundreds of young men hold mass meetings on the streets and plazas demanding democratic reforms and an end to Russian and Japanese domination, but the conservative forces prove to be too deeply entrenched for the progressive reformers, who trash the paper's offices.

The reformers, including Syngman Rhee, at this time a student leader, are jailed.

So is compelled to return to the United States in 1898, and under one pretext or another the government suppresses both the reform movement and its newspaper.

Maritime East Asia (1948–1959 CE): Cold War Divisions, Revolutionary Transformations, and Economic Foundations

Between 1948 and 1959 CE, Maritime East Asia—encompassing lower Primorsky Krai, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese Archipelago south of northern Hokkaido, Taiwan, and southern, central, and northeastern China—experiences profound transformations driven by Cold War divisions, revolutionary upheaval, ideological consolidation, and rapid economic rebuilding. The period decisively shapes regional identities, creating geopolitical alignments and lasting legacies.

China: Communist Victory and Maoist Reconstruction

In 1949, after years of civil war, Communist forces under Mao Zedong decisively defeat the Nationalist government, establishing the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on October 1. The defeated Nationalist government, led by Chiang Kai-shek, retreats to Taiwan, maintaining a rival government as the Republic of China (ROC).

The PRC initiates radical restructuring under Maoist ideology, including sweeping land reform, collectivization, and centralized economic planning. Campaigns like the Great Leap Forward (1958–1961) aim to rapidly industrialize and collectivize agriculture but result in severe famine and human suffering. Despite these setbacks, the period fundamentally reshapes China’s social, economic, and political landscape.

Korea: Division, Devastating War, and Entrenched Partition

The division of Korea at the 38th parallel solidifies in 1948, with rival states emerging: the Soviet-supported Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) under Kim Il-sung, and the U.S.-backed Republic of Korea (South Korea) led by Syngman Rhee. Tensions erupt into open conflict with the outbreak of the Korean War (1950–1953), as North Korea invades the South aiming for reunification by force.

The war devastates the peninsula, involving Chinese intervention on behalf of North Korea and extensive United Nations support for South Korea. A ceasefire in 1953 establishes the heavily fortified Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), leaving the peninsula divided, scarred by immense human and economic costs, and firmly entrenched in Cold War geopolitics.

Japan: Postwar Reconstruction and Economic Miracle Foundations

Under continued American occupation until 1952, Japan undergoes extensive political, economic, and social reforms, including democratization, land redistribution, educational reform, and economic restructuring. The San Francisco Peace Treaty (1951) formally ends the occupation, restoring Japanese sovereignty but maintaining a robust U.S. security presence.

Japan’s recovery accelerates rapidly, driven by industrial innovation, technological advancement, and government-led economic policies focused on export-oriented growth. By the late 1950s, the foundations of Japan’s future economic miracle are firmly laid, positioning the country as a rising global economic power and essential U.S. ally in the region.

Taiwan: Nationalist Refuge and Economic Reorientation

Taiwan becomes the refuge for Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government following its defeat on the mainland in 1949. Initially imposing authoritarian rule and martial law (1949–1987), the ROC government embarks on economic reforms, agricultural modernization, industrialization, and infrastructure expansion.

Taiwan’s economy experiences robust growth, aided by American economic and military support. Rapid industrialization, land reform, and improved education significantly raise living standards, transforming Taiwan into a thriving economic entity. Nevertheless, political tensions and identity debates persist, influenced by complex interactions between mainland refugees and indigenous Taiwanese populations.

Legacy of the Era: New Regional Realities and Lasting Impacts

The years 1948 to 1959 CE decisively reshape Maritime East Asia, embedding Cold War geopolitical realities into the region’s core identity. China embarks on revolutionary transformations with far-reaching consequences. The Korean Peninsula is entrenched in division, its ongoing tensions emblematic of broader ideological conflict. Japan rebuilds, laying the foundations for future economic prosperity and geopolitical significance. Taiwan consolidates economically under authoritarian rule, establishing a distinct identity amid regional complexities. Collectively, these dramatic developments profoundly influence subsequent regional dynamics, with lasting impacts on East Asian and global affairs.

Maritime East Asia (1960–1971 CE): Ideological Upheaval, Economic Expansion, and Diplomatic Realignments

Between 1960 and 1971 CE, Maritime East Asia—comprising lower Primorsky Krai, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese Archipelago south of northern Hokkaido, Taiwan, and southern, central, and northeastern China—undergoes a dramatic period marked by profound ideological upheaval, accelerated economic expansion, cultural transformation, and significant diplomatic realignments amid the backdrop of global Cold War tensions.

China: The Cultural Revolution and Internal Turmoil

Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, China plunges into the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), a decade-long political and ideological movement aimed at purging "counter-revolutionary" elements and consolidating Maoist orthodoxy. Young Red Guards, mobilized by Mao, attack perceived "bourgeois" and traditional influences, leading to widespread social disruption, persecution of intellectuals, destruction of historical artifacts, and severe damage to educational and cultural institutions.

The chaos paralyzes China's political and economic apparatus, yet solidifies Mao's control. Although the initial revolutionary zeal eventually subsides by the early 1970s, the period significantly reshapes China’s society, leaving deep scars and fundamentally altering its political trajectory.

Korea: Deepening Division, Economic Miracle in the South, Isolation in the North

The Korean Peninsula remains rigidly divided, politically and economically, between North and South. North Korea, under Kim Il-sung, adheres to rigid state-controlled economic policies emphasizing heavy industry, military strength, and self-reliance (Juche ideology), becoming increasingly isolated internationally.

Conversely, South Korea, led by authoritarian leader Park Chung-hee after a military coup (1961), begins rapid industrialization through state-directed policies, export-oriented industrial strategies, and heavy foreign investment. Park’s Five-Year Economic Plans transform South Korea into a major economic player, laying foundations for the later South Korean economic miracle (“Miracle on the Han River”), though political repression and human rights abuses accompany these achievements.

Japan: Rapid Economic Growth and Global Re-emergence

In Japan, this period is defined by unprecedented economic growth, as it fully emerges as a global economic power. The Ikeda administration’s “Income Doubling Plan” (1960–1964) dramatically accelerates economic expansion, driven by high technology industries, automotive manufacturing, electronics, and exports to Western markets.

By the late 1960s, Japan is second only to the United States in economic scale, hosting major international events like the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and 1970 Osaka World Expo—both symbols of its remarkable recovery and new status as a global economic and cultural powerhouse. Internally, political stability under the dominant Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) provides a favorable environment for sustained economic expansion.

Taiwan: Continued Economic Development and Authoritarian Rule

Under Chiang Kai-shek’s authoritarian regime, Taiwan continues its economic transformation through rapid industrialization, export-driven growth, and strategic economic planning. The development of advanced manufacturing sectors—including electronics, textiles, and petrochemicals—dramatically increases Taiwanese prosperity, earning it recognition as one of Asia’s emerging economic successes.

Despite severe political repression under continued martial law, Taiwan benefits significantly from U.S. military protection and economic support, solidifying its position within Western geopolitical alignments and laying crucial groundwork for future democratization.

Regional Diplomacy: Shifts and Realignments Amid Cold War Context

Lower East Asia also sees significant diplomatic shifts. In 1971, in a diplomatic watershed moment, the People’s Republic of China replaces the Republic of China (Taiwan) as the legitimate representative of China at the United Nations, dramatically altering international diplomatic alignments. Concurrently, Japan normalizes relations with South Korea (1965), strengthening economic cooperation. Throughout, the region remains a pivotal theater for Cold War geopolitical maneuvering.

Legacy of the Era: Transformation, Expansion, and Persistent Tensions

Between 1960 and 1971 CE, Maritime East Asia endures transformative upheaval, economic dynamism, and complex diplomatic realignment. China experiences profound ideological and social turmoil, while South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan rapidly modernize, dramatically expanding their economic influence and international roles. North Korea’s continued isolation and militarization deepen regional tensions. This dynamic period profoundly shapes East Asia’s subsequent political, economic, and diplomatic trajectories, setting lasting precedents for the region’s contemporary global significance.