Su Song

Han Chinese polymath

Years: 1020 - 1101

Su Song (1020–1101) is a renowned Han Chinese polymath who specializes as a statesman, astronomer, cartographer, horologist, pharmacologist, mineralogist, zoologist, botanist, mechanical and architectural engineer, poet, antiquarian, and ambassador of the Song Dynasty (960–1279).

Su Song is the engineer of a hydro-mechanical astronomical clock tower in medieval Kaifeng, which employs the use of an early escapement mechanism.

The escapement mechanism of Su's clock tower had previously been invented by Buddhist monk Yi Xing and government official Liang Lingzan in 725 to operate a water-powered armillary sphere, although Su's armillary sphere is the first to be provided with a mechanical clock drive.

Su's clock tower also features the oldest known endless power-transmitting chain drive, called the tian ti, or "celestial ladder", as depicted in his horological treatise.

The clock tower has 133 different clock jacks to indicate and sound the hours.

Su Song's treatise about the clock tower, Xinyi Xiangfayao, has survived since its written form in 1092 and official printed publication in 1094.

The book has been analyzed by many historians, such as Joseph Needham.

However, the clock itself is dismantled by the invading Jurchen army in 1127, and although attempts are made to reassemble the clock tower, it will never be successfully reinstated.

Although the Xinyi Xiangfayao is his best known treatise, the polymath has other works compiled as well.

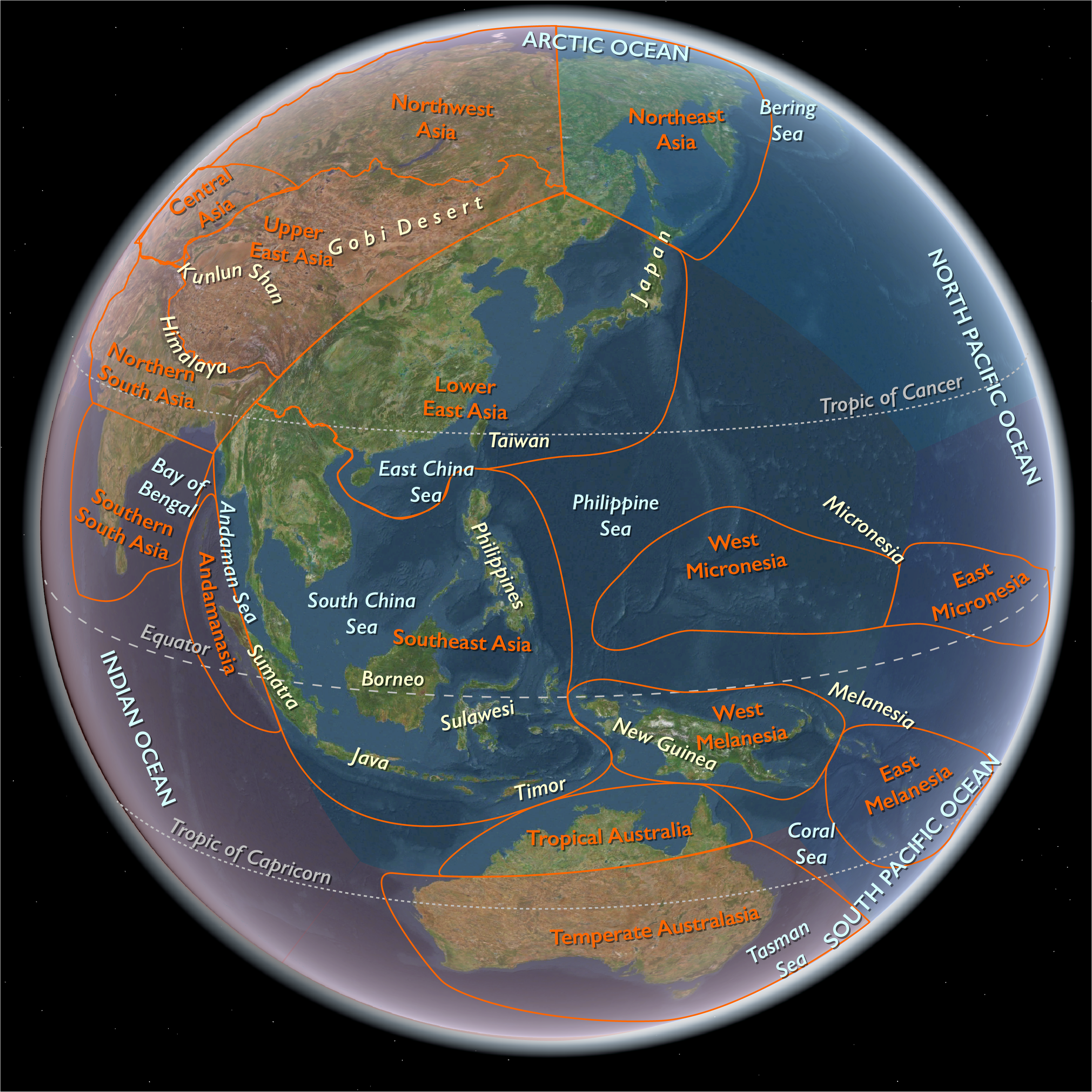

He completes a large celestial atlas of several star maps, several terrestrial maps, as well as a treatise on pharmacology.

The latter discusses related subjects on mineralogy, zoology, botany, and metallurgy.

Although later European Jesuit travelers to China, such as Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault, will briefly mention Chinese clocks with wheel drives in their writing early European visitors to China mistakenly believe that the Chinese have never advanced beyond the stage of the clepsydra, incense clock, and sundial.

They believe that advanced mechanical clockworks are new to China, and are something valuable that Europe cah offer.

Although not as prominent as in the Song period, contemporary Chinese texts of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) describe a relatively unbroken history of designs of mechanical clocks in China from the 13th to the 16th century