Saigō Takamori

Japanese samurai and politician

Years: 1828 - 1877

Saigō Takamori (Takanaga) (January 23, 1828 – September 24, 1877) is one of the most influential samurai in Japanese history, living during the late Edo Period and early Meiji Era.

He has been dubbed the last true samurai.

Born Saigō Kokichi, he receives the given name Takamori in adulthood.

He writes poetry under the name Saigō Nanshū.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 37 total

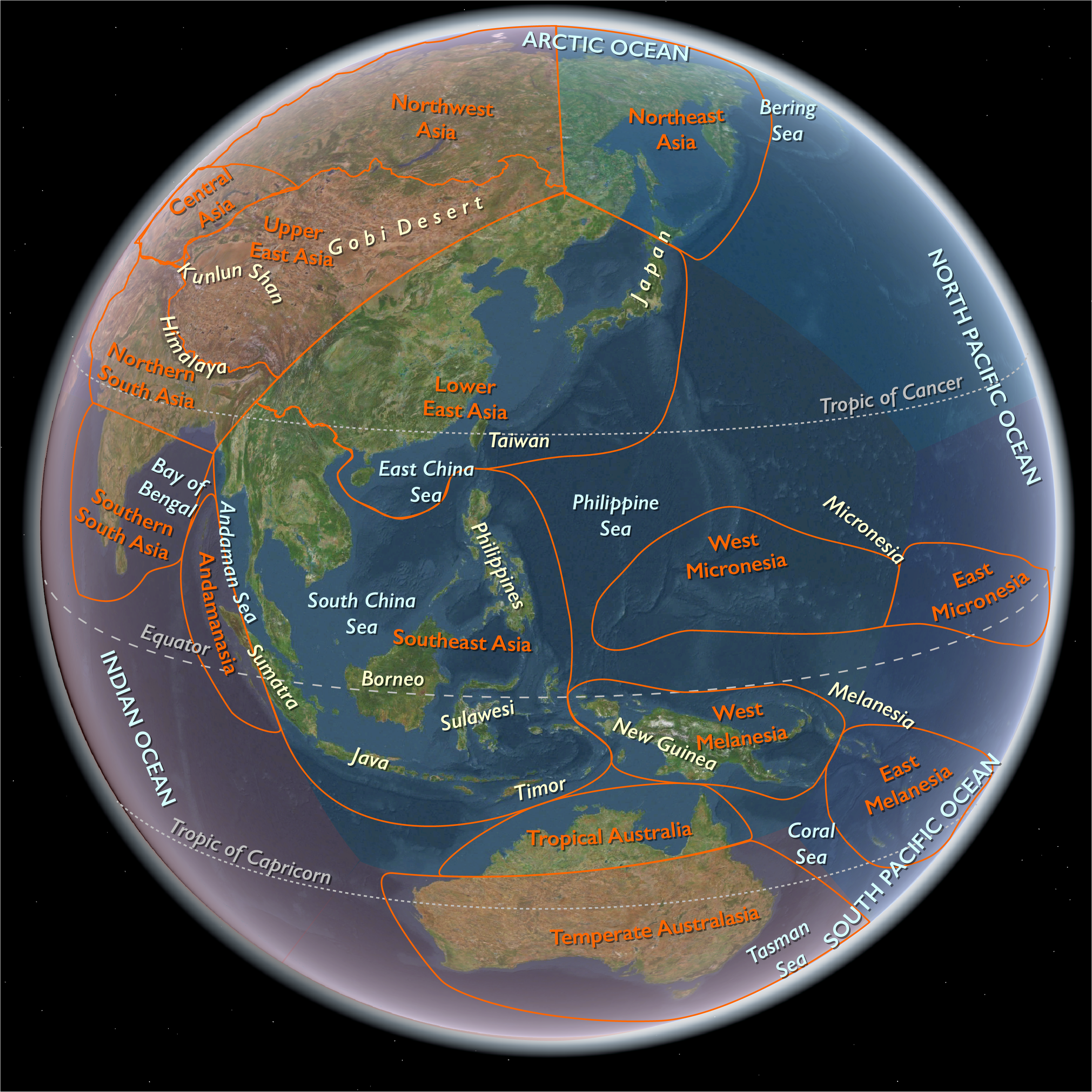

Maritime East Asia (1864–1875 CE): Restoration, Modernization, and Rising Nationalism

Between 1864 and 1875 CE, Maritime East Asia—encompassing lower Primorsky Krai, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese Archipelago south of northern Hokkaido, Taiwan, and southern, central, and northeastern China—experiences critical efforts at restoration and modernization, rising nationalist sentiments, and significant political restructuring, laying the foundations for profound regional transformations.

China: The Self-Strengthening Movement and Foreign Encroachments

Following the devastating Taiping Rebellion, Qing China embarks on the Self-Strengthening Movement, driven by scholar-generals such as Li Hongzhang and Zuo Zongtang. These leaders advocate adopting Western science, technology, and military strategies to strengthen China internally while preserving traditional political structures. Between 1861 and 1875, China sees the establishment of modern arsenals, shipyards, factories, schools, and improved diplomatic methods.

However, modernization efforts face significant internal resistance. The conservative bureaucracy, still deeply influenced by Neo-Confucian traditions, slows comprehensive reform. Simultaneously, foreign pressures intensify: Russia seizes significant territories in Manchuria, while Western powers further consolidate economic concessions through extraterritorial rights and treaty ports, severely limiting Qing sovereignty.

The Tongzhi Restoration (1862–1874), under the guidance of Empress Dowager Cixi, seeks to stabilize Qing rule through cautious reform and restoration of traditional authority. Yet, despite modest improvements, Qing China continues to struggle with internal fragmentation and external vulnerabilities.

Japan: The Meiji Restoration and Rapid Transformation

In Japan, internal conflicts culminate dramatically with the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate and the establishment of the Meiji Restoration in 1868. This marks the end of over two centuries of feudal rule, and power formally returns to the imperial court under Emperor Mutsuhito, who reigns as Emperor Meiji. The Restoration fundamentally restructures Japanese governance, aiming to modernize and centralize authority rapidly.

The Charter Oath of 1868 outlines Japan’s new goals: establishing deliberative assemblies, allowing social mobility, embracing international knowledge, and discarding outdated customs. Feudal domains (han) are abolished and replaced by prefectures, dramatically centralizing authority. Comprehensive reforms reshape the social order, economy, military, and education system, heavily influenced by Western models.

Influential leaders such as Okubo Toshimichi, Saigo Takamori, Kido Koin, and Iwakura Tomomi emerge as architects of modernization, promoting industrialization, infrastructure expansion, military enhancement, and international diplomatic engagement. A landmark diplomatic mission, the Iwakura Mission (1871–1873), travels extensively through the United States and Europe to learn and implement Western governance practices, technology, and education.

Korea: Continued Isolation and Internal Strife

Joseon Korea maintains its stringent isolationist policies amid escalating Western pressure on neighboring nations. Harsh persecution of Christians continues, reflecting deep suspicion toward foreign influence. Economic hardship intensifies due to governmental inaction and societal rigidity, fueling internal unrest and widespread poverty.

The rigid isolation contributes to deepening internal instability, setting the stage for growing social unrest and major rebellions in subsequent decades. Despite awareness of international developments in Japan and China, the Joseon court resolutely resists change, increasingly alienating progressive factions within the kingdom.

Legacy of the Era: Foundations of Modernization and Persistent Challenges

The years 1864 to 1875 CE witness crucial steps toward modernization and nation-building in Mariime East Asia. While Japan rapidly transforms into a centralized, modern nation-state, China's conservative approach limits the effectiveness of its reforms, leaving it vulnerable to continued external exploitation and internal tensions. Meanwhile, Korea’s determined isolation preserves immediate stability at the cost of long-term preparedness, foreshadowing severe challenges in the rapidly changing international environment. This era thus profoundly shapes the region’s trajectory, determining each nation’s path into the late nineteenth century.

Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901), is another influential Meiji period figure, although he never assumes a government post.

He is a prolific writer on many subjects, the founder of schools and a newspaper, and, above all, an educator bent on impressing his fellow Japanese with the merits of Westernization.

Japan is shortly to test its new world outlook.

Disputes with China over sovereignty of the Ryukyu Islands, with Russia over sovereignty of the Kurile Islands and Sakhalin, and with Korea over the Korean court's refusal to recognize the new Meiji government and its envoys will all be settled diplomatically between 1874 and 1876.

Military threats are made in the Chinese and Korean affairs, and it seems to many that Japan will soon use military means to achieve its goals.

The Meiji oligarchy, as the new ruling class will become known to historians, is a privileged clique that exercises imperial power, sometimes despotically.

The members of this class are adherents to kokugaku and believe they are the creators of a new order as grand as that established by Japan's original founders.

Two of the major figures of this group are Okubo Toshimichi (1832-78), son of a Satsuma retainer, and Satsuma samurai Saigo Takamori (1827-77), who had joined forces with Choshu, Tosa, and Hizen to overthrow the Tokugawa.

Okubo becomes minister of finance and Saigo a field marshal; both are imperial councilors.

Kido Koin (1833-77), native of Choshu, student of Yoshida Shoin, and coconspirator with Okubo and Saigo, becomes minister of education and chairman of the Governors' Conference and pushes for constitutional government.

Also prominent were Iwakura Tomomi (1825-83), a Kyoto native who had opposed the Tokugawa and is to become the first ambassador to the United States, and Okuma Shigenobu (1838-1922), of Hizen, a student of Rangaku, Chinese, and English, who will hold various ministerial portfolios, eventually becoming prime minister in 1898.

To accomplish the new order's goals, the Meiji oligarchy sets out to abolish the Tokugawa class system through a series of economic and social reforms.

Bakufu revenues had depended on taxes on Tokugawa and other daimyo lands, loans from wealthy peasants and urban merchants, limited customs fees, and reluctantly accepted foreign loans.

To provide revenue and develop a sound infrastructure, the new government finances harbor improvements, lighthouses, machinery imports, schools, overseas study for students, salaries for foreign teachers and advisers, modernization of the army and navy, railroads and telegraph networks, and foreign diplomatic missions.

Besides the old high rents, taxes, and interest rates, the average citizen is faced with cash payments for new taxes, military conscription, and tuition charges for compulsory education.

The people need more time for productive pursuits while correcting social abuses of the past.

To achieve these reforms, the old Tokugawa class system of samurai, farmer, artisan, and merchant is abolished by 1871, and, even though old prejudices and status consciousness continue, all are theoretically equal before the law.

Actually helping to perpetuate social distinctions, the government names new social divisions: the former daimyo become nobility, the samurai become gentry, and all others become commoners.

Daimyo and samurai pensions are paid off in lump sums, and the samurai later lose their exclusive claim to military positions.

Former samurai find new pursuits as bureaucrats, teachers, army officers, police officials, journalists, scholars, colonists in the northern parts of Japan, bankers, and businessmen.

These occupations help stem some of the discontent this large group feels; some profit immensely, but many are not successful and will provide significant opposition in the ensuing years.

Additionally, between 1871 and 1873, a series of land and tax laws are enacted as the basis for modern fiscal policy.

Private ownership is legalized, deeds are issued, and lands are assessed at a fair market value with taxes paid in cash rather than in kind as in pre-Meiji days and at slightly lower rates.

The Meiji leaders, undeterred by opposition, continue to modernize the nation through government- sponsored telegraph cable links to all major Japanese cities and the Asian mainland, and the construction of railroads, shipyards, munitions factories, mines, textile manufacturing facilities, factories, and experimental agriculture stations.

Much concerned about national security, the leaders make significant efforts at military modernization, which includes establishing a small standing army and a large reserve system, and compulsory militia service for all men.

Foreign military systems are studied, foreign advisers brought in, and Japanese cadets sent abroad to European and United States military and naval schools.

The Meiji leaders also modernize foreign policy, an important step in making Japan a full member of the international community.

The traditional East Asia world view is based not on an international society of national units but on cultural distinctions and tributary relationships; monks, scholars, and artists, rather than professional diplomatic envoys, had generally served as the conveyors of foreign policy.

Foreign relations are related more to the sovereign's desires than to the public interest.

For Japan to emerge from the feudal period, it has to avoid the fate of other Asian countries by establishing genuine national independence and equality.

The Meiji oligarchy is aware of Western progress, and "learning missions" are sent abroad to absorb as much of it as possible.

One such mission, led by Iwakura, Kido, and Okubo, and containing forty-eight members in total, spends two years (1871-73) touring the United States and Europe, studying government institutions, courts, prison systems, schools, the import-export business, factories, shipyards, glass plants, mines, and other enterprises.

Upon returning, mission members call for domestic reforms that will help Japan catch up with the West.

The revision of unequal treaties forced on Japan becomes a top priority.

The returned envoys also sketch a new vision for a modernized Japan's leadership role in Asia, but they realize that this role requires that Japan develop its national strength, cultivate nationalism among the population, and carefully craft policies toward potential enemies.

No longer can Westerners be seen as "barbarians," for example.

In time, Japan will form a corps of professional diplomats.

The Satsuma domain has become closer to the British, despite the bombardment of Kagoshima in 1863, and is pursuing the modernization of its army and navy with their support.

The Scottish dealer Thomas Blake Glover sells quantities of warships and guns to the southern domains.

American and British military experts, usually former officers, may have been directly involved in this military effort.

The British ambassador Harry Smith Parkes supported the anti-Shogunate forces in a drive to establish a legitimate, unified Imperial rule in Japan, and to counter French influence with the Shogunate.

During this period, southern Japanese leaders such as Saigō Takamori of Satsuma, or ...

...Itō Hirobumi and Inoue Kaoru of Chōshū cultivate personal connections with British diplomats, notably Ernest Mason Satow.