Ranavalona I

sovereign of the Kingdom of Madagascar

Years: 1778 - 1861

Ranavalona I (born Rabodoandrianampoinimerina; 1778 – August 16, 1861), also known as Ramavo and Ranavalo-Manjaka I, is sovereign of the Kingdom of Madagascar from 1828 to 1861.

After positioning herself as queen following the death of her young husband and second cousin, Radama I, Ranavalona pursues a policy of isolationism and self-sufficiency, reducing economic and political ties with European powers, repelling a French attack on the coastal town of Foulpointe, and taking vigorous measures to eradicate the small but growing Malagasy Christian movement initiated under Radama I by members of the London Missionary Society.

She makes heavy use of the traditional practice of fanompoana (forced labor as tax payment) to complete public works projects and develop a standing army of between twenty thousand and thirty thousand Merina soldiers, whom she deploys to pacify outlying regions of the island and further expand the realm.

The combination of regular warfare, disease, difficult forced labor and harsh measures of justice result in a high mortality rate among soldiers and civilians alike during her thirty-three-year reign.

Although greatly obstructed by Ranavalona's policies, French and British political interests in Madagascar remain undiminished

Divisions between traditionalist and pro-European factions at the queen's court create opportunities that European intermediaries exploit

in an attempt to hasten the succession of Ranavalona's son, Radama II.

The young prince disagrees with many of his mother's policies and is amenable to French proposals for the exploitation of the island's resources, as expressed in the Lambert Charter he concluded with a French representative in 1855.

These plans are never successful, however, and Radama II is not to take the throne until 1861, when Ranavalona dies, aged eighty-three.

Ranavalona's European contemporaries generally condemn her policies and characterize her as a tyrant at best and insane at worst.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 10 total

East Africa (1828–1971 CE)

Caravans, Kingdoms, Empires, and Independence

Geography & Environmental Context

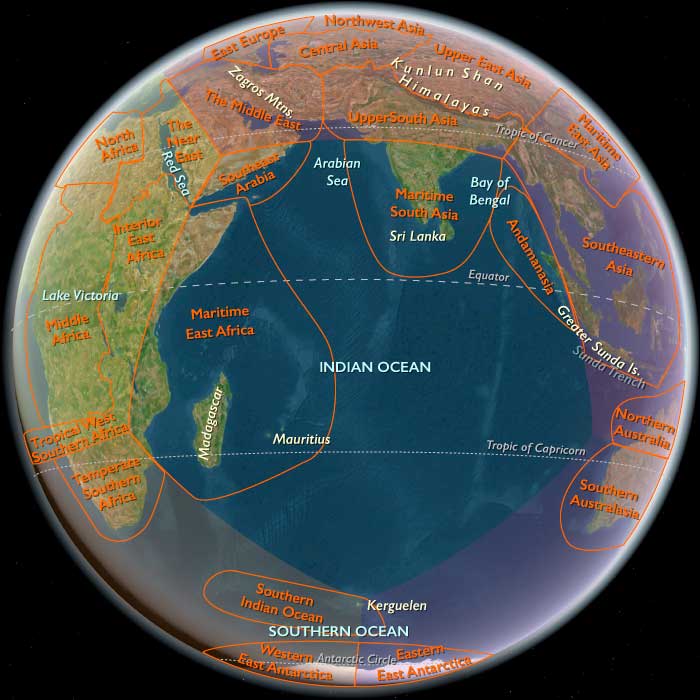

East Africa comprises two fixed subregions:

-

Maritime East Africa — Somalia, eastern Ethiopia, eastern Kenya, eastern Tanzania (including Zanzibar and Pemba), northern Mozambique, southern Malawi, and the island nations of Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, and Seychelles.

-

Interior East Africa — Eritrea, Djibouti, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia’s northwestern margin, northern Zimbabwe, northern Malawi, northwestern Mozambique, inland Tanzania, and inland Kenya.

Anchors include the Great Rift Valley, Lake Victoria, Lake Tanganyika, and Lake Malawi, the Ethiopian Highlands, the Swahili coast, and the Indian Ocean islands. The region stretches from coral coasts and monsoon ports to volcanic highlands and plateau kingdoms.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Monsoon winds sustained coastal trade, while alternating wet and dry seasons structured inland life. The late 19th century saw famine and rinderpest (1890s) devastate livestock and populations. The 20th century brought ecological engineering—railways, irrigation, and conservation parks—alongside deforestation and soil erosion. Drought cycles recurred in the Horn and interior; locusts and tsetse flies remained persistent threats. Climatic contrasts between humid coasts and arid hinterlands shaped political geography, as highland states and lowland caravan routes competed for control of trade and people.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Maritime East Africa: Coastal communities combined fishing, coral gardening, and small-scale farming of coconuts, cloves, and grains. On Zanzibar and Pemba, the clove plantations established under Sultan Seyyid Said thrived on enslaved labor. In Madagascar, the Merina Kingdom unified the central highlands and expanded wet-rice farming.

-

Interior East Africa: Highland polities such as Buganda, Bunyoro, and Ethiopia’s Shewa expanded through trade and conquest. Maize and banana cultivation sustained dense populations. After 1890, British, German, and Belgian colonial powers imposed hut taxes and cash-crop systems (cotton, coffee, sisal). Settler estates in Kenya and Tanganyika displaced African farmers; pastoralists adapted by engaging in labor markets or moving into reserves.

Technology & Material Culture

Caravan trade used oxen, donkeys, and later porters to carry ivory and slaves inland to coastal markets. The Uganda Railway (1896–1901) and the Tanga and Central Lines in German East Africa opened the interior to global commerce. Mission presses introduced literacy; railways and telegraphs expanded administration. In the 20th century, imported bicycles, radios, and sewing machines joined local crafts—basketry, textiles, wood carving, and ironwork—forming hybrid material cultures. Coastal stone architecture and carved doors persisted beside new cement towns.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Indian Ocean monsoon routes connected Zanzibar, Mombasa, Lamu, Sofala, Aden, and Bombay; dhows carried people, ivory, slaves, and spices.

-

Caravan routes—notably those of Tippu Tip and Hamed bin Muhammad—linked the interior lakes to the coast.

-

Pilgrimage and diaspora: Muslim scholars traveled to Mecca; Indian, Arab, and Comorian traders settled in coastal cities.

-

Mission and education networks: CMS, White Fathers, and Jesuits spread Christianity, schools, and medical missions inland.

-

War and liberation corridors: WWII troop movements (Abyssinia Campaign, 1940–41), Mau Mau resistance in Kenya (1952–60), and Tanzania’s and Zambia’s postwar support for southern African liberation linked East Africa to wider continental struggles.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

The Swahili language and Islamic culture unified coastal societies, while inland oral traditions preserved lineage, cattle, and warrior ideals. Christianity expanded literacy and hymnody; Islam deepened scholarly and mercantile ties. Literature, from Hamitic chronicles to Swahili poetry, blended Arabic script and local forms. In the 20th century, anticolonial writers such as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Okot p’Bitek, and Julius Nyerere’s political essays articulated new visions of identity. Coastal music (taarab) and inland dances symbolized cultural fusion.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Rotational cultivation and fallowing preserved soil fertility; pastoralists tracked rainfall patterns and rebuilt herds after rinderpest. Irrigation terraces in Ethiopia, banana groves in Buganda, and shifting cultivation in Madagascar reflected ecological diversity. In the 20th century, national parks (e.g., Serengeti, 1951; Tsavo, 1948) institutionalized conservation but often displaced local communities. Rural cooperatives, ujamaa villages, and community irrigation projects (1960s–70s) reflected adaptation to postcolonial development goals.

Political & Military Shocks

-

Colonial conquest: The Scramble for Africa (1880s–90s) divided the region among Britain, Germany, Belgium, France, and Portugal.

-

Ethiopia’s resilience: The Battle of Adwa (1896) preserved Ethiopian independence under Menelik II; Italian invasion (1935–41) under Mussolini was defeated in WWII with Allied support.

-

Resistance and uprisings: The Maji Maji Rebellion (1905–07) in German East Africa, the Hehe resistance, and the Somali Dervish movement (1899–1920) testified to enduring autonomy.

-

World Wars: East Africa was a key front in both conflicts; labor and resources were conscripted for imperial armies.

-

Decolonization:

-

Tanzania (1961), Uganda (1962), Kenya (1963), Malawi (1964), Zambia (1964), and Madagascar (1960) achieved independence.

-

Somalia unified its British and Italian territories (1960); Comoros and Mauritius followed later in the 1970s.

-

Eritrea was federated with Ethiopia (1952) and annexed (1962), sowing seeds of later conflict.

-

Regional federations such as the East African Community (1967) sought economic unity.

-

Transition

Between 1828 and 1971, East Africa transformed from a network of coastal sultanates and caravan kingdoms into a mosaic of colonial states and independent nations. The Swahili coast, once dominated by monsoon commerce and slavery, gave way to global trade in cash crops and labor migration. Inland, Christianity, Islam, and anticolonial nationalism remade political identity. Railways and cash crops reoriented the economy; liberation movements redrew its moral geography. By 1971, East Africa had become a region of independent states—from Ethiopia’s highlands to Madagascar’s forests—poised between the legacies of empire and the aspirations of Pan-African renewal.

Maritime East Africa (1828–1971 CE): Clove Empires, Colonial Partition, and Island Independence

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of Maritime East Africa includes Somalia, eastern Ethiopia, eastern Kenya, eastern Tanzania and its islands, northern Mozambique, the Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, and Seychelles. Anchors included the Swahili ports of Zanzibar, Mombasa, and Mogadishu; the clove plantations of Zanzibar and Pemba; the rice terraces of the Merina highlands in Madagascar; and the sugar estates of Mauritius and Seychelles. From coral rag coasts and mangrove estuaries to highland terraces and volcanic islands, this littoral zone became both a hub of global commerce and a theater of European colonization.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The retreat of the Little Ice Age brought warming trends, though coastal and island regions continued to experience cyclones and drought cycles. Zanzibar endured periodic clove crop failures from pests and storms. Madagascar’s south suffered recurrent drought, while highland rice fields stabilized production. Mauritius and Seychelles faced hurricanes that devastated sugar and coconut crops. Coastal fisheries remained resilient but faced pressure from expanding populations and trade.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Zanzibar and Pemba: Became global centers of clove cultivation under Omani sultans, relying on enslaved Africans from the mainland. Rice, cassava, and coconuts sustained islanders; fishing and trade supplemented diets.

-

Swahili coast (Kenya–Tanzania–Mozambique): Farmers grew millet, cassava, and maize in coastal hinterlands; fishing and mangrove harvesting persisted. Towns expanded around ports linked to Indian Ocean trade.

-

Somalia and eastern Ethiopia: Pastoralists herded camels, sheep, and goats, supplementing with sorghum and date cultivation in oases.

-

Madagascar: The Merina kingdom centralized power under Radama I and successors, expanding rice terraces and cattle herding; coastal groups (Sakalava, Betsimisaraka) farmed, fished, and engaged in maritime trade.

-

Comoros: Mixed subsistence of rice, cassava, coconuts, and fishing; cloves planted in the 19th century tied islands into world markets.

-

Mauritius and Seychelles: Sugar estates dominated, worked by enslaved laborers until emancipation (1830s–1840s) and later Indian indentured migrants; coconuts and spices diversified production.

Technology & Material Culture

Omani rulers built stone palaces, forts, and clove-processing houses in Zanzibar. Dhows remained central for Indian Ocean trade, carrying cloves, ivory, and slaves. Imported firearms armed coastal elites. In Madagascar, Merina kings constructed fortified hill capitals and expanded irrigation systems. French colonists introduced European-style architecture and mills in Madagascar, Comoros, Mauritius, and Seychelles. Textiles, pottery, and coral-stone mosques continued Swahili traditions; in the Mascarenes, creole architecture and music blended African, European, and Indian influences.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Slave and ivory trade: In the early 19th century, dhows carried enslaved Africans from mainland ports (Bagamoyo, Kilwa, Mozambique Island) to Zanzibar and beyond; ivory caravans reached deep into the interior.

-

Abolition: Britain pressured Zanzibar into anti-slavery treaties (1822, 1873), though clandestine trade persisted into the late 19th century.

-

Colonial partition: Britain took Kenya, Zanzibar (protectorate, 1890), and Somaliland; Germany claimed Tanganyika; France colonized Madagascar (1896) and the Comoros; Portugal retained Mozambique. Mauritius and Seychelles passed to Britain (1810).

-

Labor migrations: Indian indentured workers moved to Mauritius, Seychelles, and coastal East Africa. African porters staffed ivory and rubber caravans inland.

-

20th-century transport: Railways (Uganda Railway to Mombasa, Tanga line) tied coast to interior; steamships and later air links bound islands to global routes.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Swahili Islamic culture thrived in mosques, Qur’anic schools, and poetry; Omani rule reinforced Arabic scholarship. The Zanzibar court became a symbol of coastal Islamic power. In Madagascar, Merina rulers blended traditional rituals with European-style monarchy until French conquest. Catholic and Protestant missions spread across the coast, Madagascar, and the islands, establishing schools and churches. Creole cultures flourished in Mauritius and Seychelles, expressed in séga music, cuisine, and festivals. Oral traditions, ancestor veneration, and ritual feasts persisted across the subregion.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Farmers incorporated cassava, maize, and cloves to buffer crop failures. Pastoralists shifted herds seasonally in Somali and Ethiopian lowlands. Merina highlanders expanded rice terraces, securing resilience against famine. After emancipation, plantation societies adapted through indentured labor systems. Coastal and islanders rebuilt after cyclones, diversifying crops and relying on fishing. Conservation initiatives began mid-20th century, especially in Madagascar’s forests and island ecosystems.

Technology & Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

-

Omani Zanzibar: Under Said bin Sultan, Zanzibar became a clove empire and slave entrepôt; later sultans governed under British oversight.

-

Colonial conquest: France subdued Madagascar (1896); Germany ruled Tanganyika until World War I, when Britain assumed control. Somalia was partitioned between Britain, Italy, and France. Portugal tightened rule in Mozambique.

-

Resistance: Local revolts resisted colonial demands—e.g., Maji Maji Rebellion (1905–1907) in German East Africa. Malagasy uprisings (1947) challenged French rule.

-

Independence movements: Mauritius (1968), Somalia (1960), Madagascar (1960), Comoros (1975, just beyond this span), and Seychelles (1976, also just beyond) emerged from decolonization. Zanzibar’s revolution (1964) overthrew the sultanate, uniting with Tanganyika to form Tanzania.

Transition

By 1971 CE, Maritime East Africa had been transformed from a Swahili–Omani corridor into a mosaic of colonial and postcolonial states. Zanzibar’s clove plantations, Madagascar’s rice highlands, and Mauritius’s sugar estates tied the region to global markets, even as nationalist movements reshaped politics. Swahili culture, Islamic learning, and Malagasy ritual traditions persisted alongside new Christian and creole identities. Maritime East Africa entered the modern era as both a crossroads of global trade and a crucible of independence struggles.

Maritime East Africa (1828–1839 CE): Abolition, Social Transformation, and Political Reaction

From 1828 to 1839 CE, Maritime East Africa—including Mauritius, Seychelles, Madagascar, and the Swahili Coast—undergoes pivotal transformations marked by the abolition of slavery, profound social restructuring, significant missionary influence, and complex political dynamics.

Mauritius: Abolition of Slavery and Economic Transition

In Mauritius, plantation owners of French origin (Franco-Mauritians) have vigorously resisted British efforts to abolish slavery. Nevertheless, under sustained British pressure, slavery is finally abolished in 1835. To appease the powerful planter class, the British government grants substantial concessions, including financial compensation totaling £2.1 million and enforced "apprenticeship" for former enslaved persons, compelling them to remain on plantations for another six years.

However, widespread desertions among the so-called apprentices create a severe labor shortage, forcing authorities to abandon the apprenticeship system in 1838, two years ahead of schedule. This abrupt shift dramatically reshapes the island's economy, leading to increased reliance on indentured laborers from India in subsequent decades.

Seychelles: Post-Abolition Migration and Cultural Integration

In the Seychelles, slavery is abolished in 1834, triggering a significant demographic and social shift. Many impoverished European settlers leave the islands, taking their former slaves with them. Subsequently, the British navy brings in large numbers of liberated Africans, rescued from slave ships intercepted along the East African coast, dramatically altering the islands’ demographic makeup.

The arrival of small groups of traders from China, Malaysia, and India adds to this diversity, with these groups primarily engaging in commerce. A pattern of extensive intermarriage among African, European, and Asian populations emerges (with the notable exception of the Indian community), creating a highly mixed society. By 1911, racial classifications become effectively meaningless due to this extensive integration and are ultimately abandoned.

Madagascar: Radical Reform and Conservative Backlash

In Madagascar, Radama I (r. 1810–1828) had significantly modernized and centralized the island’s administration, inviting Protestant missionaries from the London Missionary Society to establish schools, introduce the printing press, and devise a written form of the local language (Malagasy), using the Latin alphabet. By 1828, thousands of Merina individuals had become literate, and a select few students traveled to Britain for education. These efforts dramatically reshape the cultural landscape, fostering the development of a literate Merina elite and widespread Protestant conversion.

The accession of Queen Ranavalona I (r. 1828–1861) marks a stark shift. Reacting strongly against foreign influence, Ranavalona I's reign is characterized by isolationism, persecution of Protestant converts, and stringent control over trade. Many Europeans flee, although a privileged few, such as the French artisan Jean Laborde, continue to enjoy special favor. Laborde establishes a significant manufacturing complex at Mantasoa, near Antananarivo, producing silk, soap, guns, tools, and cement, highlighting a paradoxical embrace of limited modernization within a broadly reactionary political framework.

Swahili Coast: Omani Influence and Local Resistance

On the Swahili Coast, Omani control remains robust, notably under Sultan Sa'id bin Sultan, who asserts his authority firmly against local resistance—especially in strategically important cities like Mombasa and islands such as Zanzibar and Pemba. British naval forces temporarily intervene (1824–1826) on behalf of Oman but eventually withdraw. Continued local resistance, notably from the Mazrui dynasty, persists, reflecting sustained tension between Omani rulers and indigenous populations.

Malawi and Mozambique:

In the early nineteenth century, southern Malawi sees the establishment of missionary settlements, particularly the Scottish-founded town of Blantyre (named after the birthplace of explorer David Livingstone). These missions introduce new economic and agricultural practices, gradually transforming regional socioeconomic patterns. Meanwhile, central and northern Mozambique continue under Portuguese influence, their coastal settlements serving as pivotal hubs for trade in ivory, gold, and enslaved people, maintaining regional economic significance amid growing European imperial interests.

Legacy of the Age

The period from 1828 to 1839 CE in Maritime East Africa is marked by significant social and political transformations: the end of institutional slavery profoundly reshapes economic structures in Mauritius and Seychelles, triggering demographic and cultural shifts. Madagascar experiences dramatic swings between progressive modernization and conservative isolationism, profoundly influencing its political and social trajectory. The Swahili Coast continues its complex interplay between Omani dominance and resilient local identities, setting the stage for further colonial and imperial contests in the coming decades.

The reign of Radama I's wife and successor, Queen Ranavalona I (r. 1828-61), is essentially reactionary, reflecting her distrust of foreign influence.

Under the oligarchy that rules in her name, rivals are slain, numerous Protestant converts are persecuted and killed, and many Europeans flee the island.

The ruling elite holds all the land and monopolizes commerce, except for the handful of Europeans allowed to deal in cattle, rice, and other commodities.

Remunerations to the queen provided the French traders a supply of slaves and a monopoly in the slave trade.

Enjoying particular favor owing to his remarkable accomplishments is French artisan Jean Laborde, who establishes at Mantasoa, near Antananarivo, a manufacturing complex and agricultural research station where he manufactures commodities ranging from silk and soap to guns, tools, and cement.

Radama I's interest in modernizing Madagascar along Western lines extends to social and political matters.

He had organized a cabinet and encouraged the Protestant London Missionary Society to establish schools and churches and to introduce the printing press—a move that is to have far-reaching implications for the country.

The society will make nearly half a million converts, and its teachers have devised a written form of the local language, Malagasy, using the Latin alphabet.

By 1828 several thousand persons, primarily Merina, have become literate, and a few young persons are being sent to Britain for schooling.

Later the Merina dialect of Malagasy will become the official language.

Malagasy-language publications are established and circulated among the Merina-educated elite; by 1896 some one hundred and sixty-four thousand children, mainly Merina and Betsileo, will have attended the mission's primary schools.

Along with new ideas come some development of local manufacturing.

Much productive time is spent, however, in military campaigns to expand territory and acquire slaves for trade.

The reign of Madagascarene Queen Ranavalona I (Ranavalona the Cruel), the widow of Radama I, begins inauspiciously with the queen murdering the dead king’s heir and other relatives.

The aristocrats and sorcerers (who had lost influence under the liberal régime of the previous two Merina kings) re-assert their power during the Queen’s reign, which is to last thirty-three years.

The queen has repudiated the treaties that Radama I had signed with Britain.

Emerging from a dangerous illness in 1835, she credits her recovery to the twelve sampy, the talismans—attributed with supernatural powers—housed on the palace grounds.

To appease the sampy who had restored her health, she issues a royal edict prohibiting the practice of Christianity in Madagascar, expels British missionaries from the island, and persecutes Christian converts who will not renounce their religion.

Christian customs “are not the customs of our ancestors”, she explains.

The queen scraps the legal reforms started by Andrianampoinimerina in favor of the old system of trial by ordeal.

People suspected of committing crimes—most go on trial for the crime of practicing Christianity—have to drink the poison of the tangena tree.

If they survive the ordeal (which few do) the authorities judge them innocent.

Malagasy Christians will remember this period as ny tany maizina, or "the time when the land was dark".

By some estimates, one hundred and fifty thousand Christians die during the reign of Ranavalona the Cruel.

The island grows more isolated, and commerce with other nations comes to a standstill.

Maritime East Africa (1840–1851 CE): European Territorial Gains, Economic Shifts, and Religious Persecution

From 1840 to 1851 CE, Maritime East Africa—including Madagascar, the Seychelles, Mauritius, and the Comoros Islands—experiences intensified European territorial ambitions, significant economic and demographic transformations following the abolition of slavery, and continued religious persecutions under Madagascar’s conservative regime.

French Territorial Expansion in Madagascar and Comoros

In 1840, France expands its colonial presence in the region by acquiring the island of Nosy-Be, off the northwestern coast of Madagascar. Though strategically significant, the island’s potential as a major port remains limited. In 1841, Admiral de Hell, Governor of Réunion, negotiates the cession of Mayotte (Mahore) from Andriantsoly, known as the King of Mayotte and leader of the Sakalava in northwestern Madagascar. Mahore’s potential for port facilities makes it a strategically valuable acquisition. Admiral de Hell justifies the move by asserting that if France hesitates, Britain will seize the island first.

These territorial acquisitions underscore France's growing strategic interest in the region, intended both to bolster its Indian Ocean naval presence and counterbalance British colonial ambitions.

Seychelles: Post-Abolition Economic and Social Changes

In the Seychelles, abolition of slavery (1834) leads to profound economic and social shifts by this period. Formerly enslaved Seychellois, who once produced cotton, coconut oil, spices, coffee, and sugarcane, shift away from labor-intensive agriculture following emancipation. By 1840–1851, many become wage laborers, sharecroppers, fishers, artisans, or informal settlers on available land.

Plantation agriculture transitions toward less labor-intensive cash crops like copra, cinnamon, and vanilla. This shift dramatically alters the islands' economic landscape, leading to the decline of intensive farming and increasing dependency on imported basic necessities, including food and manufactured goods. The islands' population grows increasingly reliant on trade, and economic activity focuses primarily on processing cash crops and exploiting natural resources rather than extensive cultivation.

Malawi and Mozambique:

During this era, Portuguese-controlled central Mozambique expands its role as a critical nexus for trade routes penetrating the African interior, facilitating commerce between southern Malawi and coastal ports like Quelimane and Beira. Southern Malawi increasingly feels the impact of external contacts, notably via missionary expeditions and early European exploration, beginning to shift local economies toward export-oriented production. The emergence of Blantyre as a mission and trading center marks the early stages of Malawi's integration into broader colonial networks.Madagascar: Religious Persecution under Queen Ranavalona I

In Madagascar, the reign of Queen Ranavalona I (r. 1828–1861) is marked by intensifying persecution of Christian converts, particularly targeting converts influenced by British Protestant missionaries. Accurate numbers of executions are difficult to ascertain, but the British missionary W.E. Cummins (1878) estimates between sixty and eighty executions for religious reasons during Ranavalona's reign, with many more suffering severe punishment, imprisonment, loss of property, or death through forced labor and harsh ordeals.

Persecutions peak notably in 1840, 1849, and later in 1857. The year 1849 proves particularly severe, with nineteen individuals facing harsh punishment due to their adherence to Christianity, eighteen of whom are executed. These religious persecutions underscore Ranavalona's reactionary and isolationist policies, driven by her deep distrust of foreign influence and her determination to preserve traditional Merina culture and authority.

Legacy of the Era

The era from 1840 to 1851 CE shapes Maritime East Africa through territorial expansion by European colonial powers, marked socio-economic shifts following emancipation, and the reactionary religious persecutions in Madagascar. French territorial acquisitions presage greater colonial involvement, while economic transformations following abolition reshape the Seychelles’ social landscape. In Madagascar, the intensifying religious persecution further isolates the Merina kingdom, setting the stage for greater external intervention in subsequent decades.

British missionary to Madagascar W.E. Cummins (1878) will place the number executed at between sixty and eighty.

Far more are required to undergo the tangena ordeal, condemned to hard labor, or stripped of their land and property, and many of these die.

Persecution of Christians intensifies in 1840, 1849 and 1857; in 1849, deemed the worst of these years by Cummins, nineteen people are fined, jailed or otherwise punished for their Christian faith, of whom eighteen are executed.

Maritime East Africa (1852–1863 CE): British Influence, Economic Expansion, and Madagascar's Political Shifts

From 1852 to 1863 CE, Maritime East Africa—including the Somali coast, Mauritius, and Madagascar—experiences expanding British influence, significant economic developments tied to global markets, and notable political shifts within Madagascar’s Merina kingdom.

Somali Coast: Local Rule and British Relations

In 1854–1855, British naval lieutenant Richard Burton explores the northern Somali coast, observing significant local political autonomy despite formal foreign influences. At Saylac, Burton encounters Somali governor Haaji Sharmarke Ali Saleh of the Habar Yoonis clan, who exerts practical authority over the city and its surroundings. However, Saylac itself has significantly declined from its former prominence, now characterized by crumbling infrastructure, ineffective water storage, and recurrent incursions by local tribal groups.

Farther east along the Majeerteen (Bari) coast, two influential Somali kingdoms emerge prominently: the Majeerteen Sultanate under Boqor Osman Mohamoud, and the Sultanate of Hobyo (Obbia) under Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid. Sultan Osman Mohamoud’s leadership sees considerable economic growth from trading in livestock, ostrich feathers, and gum arabic, enhanced by British subsidies intended to protect British shipwreck survivors along the Somali coastline. Although nominally acknowledging British influence, these Somali kingdoms maintain considerable autonomy well into the nineteenth century.

Mauritius: Sugar Dominance under British Rule

In Mauritius, sugar production becomes the island’s dominant economic sector, significantly shaping its colonial economy under British administration. Initially incentivized by Britain’s decision in 1825 to equalize sugar duties across colonies, Mauritius dramatically expands its sugar output. From 1825 to 1826, production nearly doubles, and by 1854, the island surpasses one hundred thousand tons annually. Between 1855 and 1859, Mauritius achieves its peak significance as Britain’s primary sugar-producing colony, contributing 9.4 percent of the global sugar supply.

Despite rising overall production through subsequent decades, Mauritius’s global sugar dominance gradually diminishes due to declining world sugar prices and intensified competition from other sugar-producing nations. Nevertheless, the concentration on sugar transforms the island’s economy, diminishing food-crop cultivation and reinforcing large, plantation-based landholdings.

Madagascar: Political and Diplomatic Fluctuations under Merina Rule

Madagascar’s political environment undergoes significant swings during this era. Under King Radama II (r. 1861–1863), Madagascar adopts a notably pro-European stance, particularly toward France. Radama II signs a treaty of perpetual friendship with France, signifying openness to Western influence and modernization. However, his policies quickly provoke opposition from conservative nobles alarmed by the increasing French presence.

In 1863, Radama II is assassinated by nobles opposed to his pro-French diplomacy, abruptly ending his short reign. His widow, Queen Rasoherina (r. 1863–1868), succeeds him, swiftly reversing his policies. She annuls the French treaty and dissolves agreements made by Radama II, including revoking the charter of the influential French entrepreneur Jean Laborde, whose ventures had significantly shaped Madagascar’s industrial and agricultural landscape.

Malawi and Mozambique:

The mid-nineteenth century witnesses increased Portuguese administrative presence in central and northern Mozambique, though practical control remains patchy beyond coastal enclaves. Mozambique’s Zambezi Valley becomes a crucial artery for trade, linking inland southern Malawi settlements, including expanding missionary bases, to coastal markets. Blantyre grows steadily, influenced by increasing missionary activity and early plantation economies introduced by European settlers, setting foundations for its future status as Malawi’s commercial and administrative hub.

Legacy of the Era

The period from 1852 to 1863 CE in Maritime East Africa is marked by expanding British influence along the Somali coast, economic prosperity driven by sugar cultivation in Mauritius, and dramatic political and diplomatic shifts within Madagascar’s Merina kingdom. These developments profoundly shape regional dynamics, setting a foundation for intensified European colonial interactions and economic transformations in subsequent decades.