Naemul of Silla

17th ruler of the kingdom of Silla

Years: 330 - 402

Naemul of Silla (died 402) (r. 356–402) is the 17th ruler of the Korean kingdom of Silla.

He is the nephew of King Michu.

He married Michu's daughter, Lady Boban.

He is given the title Isageum, the same one borne by earlier rulers, in the Samguk Sagi; he is given the title Maripgan, borne by later rulers, in the Samguk Yusa.

He is the first to bear the title Maripgan in any record.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 7 events out of 7 total

King Naemul (356–402) of the Kim clan establishes a hereditary monarchy in Silla, eliminating the rotating power-sharing scheme.

The leader's title, now truly royal, becomes Maripgan (from the native Korean root Han or Gan, "leader" or "great", which was previously used for ruling princes in southern Korea, and which may have some relationship with the Mongol/Turkic title Khan).

Naemul's later reign is troubled by recurrent invasions by Wa (Japan) and the northern Malgal (Mohe) tribes, sometimes considered the ancestors of the Jurchens, modern-day Manchus and other Tungusic peoples.

This begins with a massive Japanese incursion in 364, which is repulsed with great loss of life.

King Naemul of Silla is the first king to appear by name in Chinese records.

It appears that there was a great influx of Chinese culture into Silla in his period, and that the widespread use of Chinese characters begins in his time.

In 381, Silla sends emissaries to China and establishes relations with Goguryeo.

Maritime East Asia (388–531 CE): Consolidation of States, Cultural Flourishing, and Technological Advancements

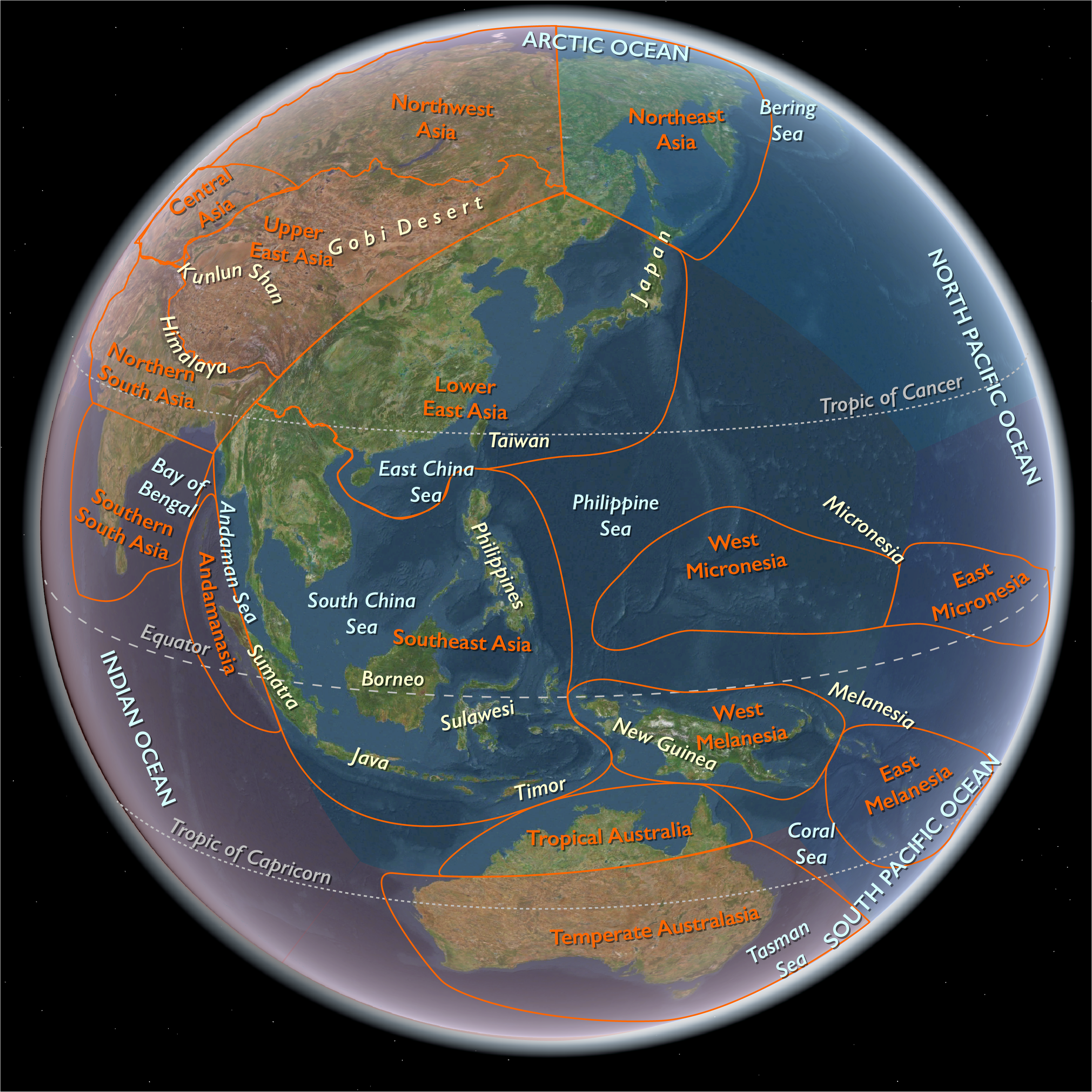

Between 388 CE and 531 CE, Maritime East Asia—comprising lower Primorsky Krai, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese Archipelago below northern Hokkaido, Taiwan, and southern, central, and northeastern China—witnesses the consolidation of major kingdoms, cultural flourishing, and important technological innovations.

Consolidation and Expansion in Korea: Silla, Baekje, and Goguryeo

Silla, evolving from the walled town of Saro, is consolidated under King Naemul (r. 356–402), establishing a hereditary monarchy east of the Naktong River. By the early sixth century, Silla significantly advances agricultural productivity through oxen plowing and extensive irrigation, enabling greater political stability and cultural development. In 520 CE, an administrative code is adopted, followed by Buddhism becoming the state religion around 535 CE. The bone-rank system emerges, codifying an aristocratic social hierarchy where status and lineage are paramount.

Baekje, after successfully repelling an attack from the Chinese-held region of Lelang in 246 CE, maintains its influential aristocratic state structure, integrating Buddhism officially as the state religion in 384 CE under royal patronage.

Goguryeo, a formidable northern power, continues expansion into Lelang and the broader Korean Peninsula. Its geographic position, marked by harsh climates and mountainous terrain, strengthens its distinct cultural identity, later emphasized in North Korean historiography.

The Gaya Confederacy, consisting of states along the south-central peninsula, maintains close ties with Japan but is eventually absorbed by Silla, despite Japanese military intervention on Gaya’s behalf in 399 CE.

The Yamato Polity and Aristocratic Transformation in Japan

In Japan, the Yamato polity emerges prominently in the mid-Kofun period, defined by influential great clans. Clan patriarchs perform sacred rites to ensure welfare, with a hereditary aristocracy beginning to replace tribal leadership structures. Aristocratic status increasingly determines political influence, shifting power dynamics away from purely clan-based hierarchies.

Political Fragmentation and Cultural Flourishing in China

China experiences continued political fragmentation during the Sixteen Kingdoms (304–439 CE) and the subsequent Southern and Northern Dynasties period (420–589 CE). Despite persistent warfare and instability, this era is culturally vibrant, characterized by advancements in art, science, and religion.

Significant technological innovations include the widespread adoption of the stirrup by 477 CE, enhancing military effectiveness. Additionally, Chinese architecture evolves distinctly, with the development of the pagoda, derived from Buddhist stupa traditions, becoming prominent for housing Buddhist scriptures.

Buddhism and Cultural Exchange

Buddhism spreads widely across China, notably through the influential translations by Kumarajiva, facilitating its integration into Chinese society. By the late fifth century, the distinct Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism emerges prominently, attributed to the teachings of Bodhidharma, emphasizing contemplative meditation as a pathway to enlightenment.

Artistic and Architectural Achievements

Monumental stone sculpture flourishes, exemplified by the Yungang Grottoes near Pingcheng (modern-day Datong). Under imperial patronage of the Northern Wei Dynasty, the caves house immense rock-cut Buddha sculptures, showcasing Central Asian artistic influences. This monumental art form persists through imperial and private support until political upheavals halt further construction by 525 CE.

Legacy of the Age: State Consolidation and Cultural Innovation

Thus, the age from 388 to 531 CE is marked by significant state consolidation, particularly in Korea and Japan, combined with cultural and technological innovations across East Asia. These developments lay foundational structures influencing political, social, and cultural trajectories well into subsequent centuries.

Silla evolves from a walled town called Saro.

Silla chroniclers are said to have traced its origins to 57 BCE, but contemporary historians have regarded King Naemul (r. CE 356-402) as the ruler who first consolidates a large confederated kingdom and establishes a hereditary monarchy.

His domain is east of the Naktong River in today's North Kyongsang Province.

A small number of states located along the south-central tip of the peninsula facing the Korea Strait do not join either Silla or Baekje but instead form the Gaya Confederacy, which maintains close ties with states in Japan.

Silla eventually absorbs the neighboring Gaya states in spite of an attack by Wa forces from Japan on behalf of Gaya in 399, which Silla repels with help from Goguryeo.

Centralized government probably emerges in Silla in the second half of the fifth century, as the capital became both an administrative and a marketing center.

In the early sixth century, Silla's leaders introduce plowing by oxen and build extensive irrigation facilities.

Increased agricultural output presumably ensues, allowing further political and cultural development, including an administrative code in 520, a hereditary caste structure known as the bone-rank system to regulate membership of the elite, and the adoption of Buddhism as the state religion around 535.

Status in Silla society is so much influenced by birth and lineage that the bone-rank system leads each family and clan to maintain extensive genealogical records with meticulous care.

Because only male offspring prolong the family and clan lines and are the only names registered in the genealogical tables, the birth of a son is greeted with great felicitation.

The elite, of course, is most conscious of family pedigree.

Silla submits to Goguryeo in 399 for protection from raids from Baekjae.

Many consider this loose unification under Goguryeo to have been the first and only true unification of the Three Kingdoms.

Many peasants are said to have fled to Silla during another round of conscription by Asin of Baekje for the battles against Goguryeo in 399.

Silla, another Korean kingdom in the southeast of the peninsula, requests the assistance of Goguryeo in 400 to defend against an alliance of a Japanese army, the Baekje kingdom to the west, and the Gaya Confederacy to the southwest.

In the same year, King Gwanggaeto responds with fifty thousand troops, defeats both Japanese and Gaya cavalry units, and makes both Silla and Gaya submit to his authority.