Mohammad Shah Qajar

Shahanshah of Persia

Years: 1808 - 1848

Mohammad Shah Qajar (born Mohammad Mirza) (5 January 1808 – 5 September 1848) is king of Persia from the Qajar dynasty (23 October 1834 – 5 September 1848).

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 6 events out of 6 total

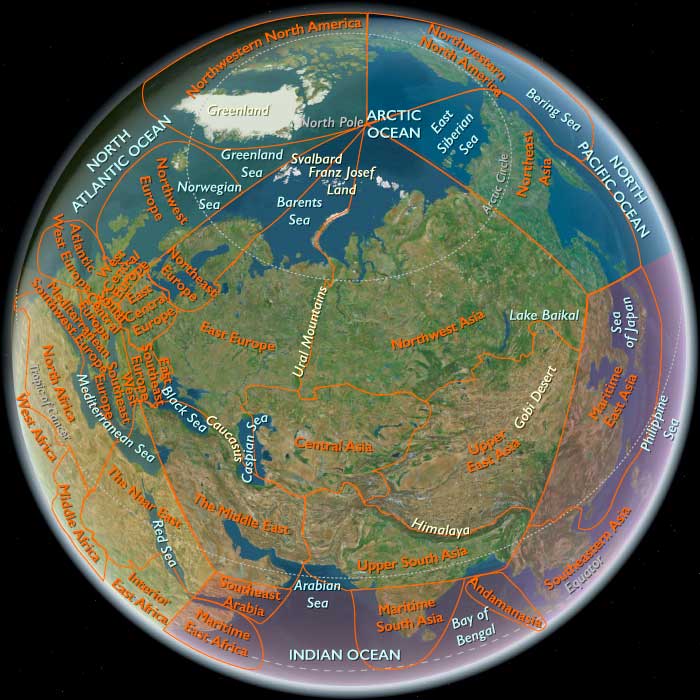

The Middle East: 1828–1839 CE

Egyptian Dominance and Ottoman Reforms

From 1828 onward, Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt consolidates his position as a major autonomous ruler within the Ottoman Empire, significantly influencing Middle Eastern politics. Muhammad Ali modernizes Egypt’s military and administration, turning it into a formidable regional power. In 1831, his son Ibrahim Pasha invades and occupies Syria, Palestine, and parts of Anatolia, threatening Ottoman stability and nearly capturing Constantinople itself by 1833. Assisted by Bashir II of Mount Lebanon, who allies with Muhammad Ali, Ibrahim captures Acre in May 1832 after a seven-month siege and Damascus soon afterward. However, Ibrahim’s centralization policies, taxation, and conscription efforts become unpopular, and Ottoman forces ultimately expel Egyptian rule from Syria by 1839. The Treaty of Hünkâr İskelesi (1833) temporarily resolves tensions, granting Russia increased influence in Ottoman affairs in exchange for protecting the empire from Egyptian threats.

Saudi-Wahhabi Consolidation

The Al Saud-Wahhabi state under Turki ibn Abd Allah continues to solidify its power in central Arabia. Turki governs from his capital at Riyadh, successfully reclaiming territories lost after the Egyptian occupation and retaking Ad Diriyah in 1821. His administration emphasizes Wahhabi religious principles to reinforce political authority, further spreading Wahhabism throughout the Arabian Peninsula. Turki’s swift reclamation of Najd demonstrates the entrenched nature of Saudi-Wahhabi influence, rooted in religious authority. The Al Saud levy troops from loyal tribes, conduct raids termed as jihads, and collect tribute based on Islamic law. Turki maintains a delicate balance, cooperating with the Ottomans by forwarding tribute from Oman, yet he contends with internal family conflicts and external pressures, including occasional Ottoman interference and rising British influence in the Gulf.

Qajar Persia and Continued Territorial Losses

Persia under Fath-Ali Shah Qajar and later his grandson Mohammad Shah Qajar (1834–1848) continues struggling against internal dissent and external pressures, particularly from Russia and Britain. The Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), following Persia’s defeat in the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828), imposes harsh terms, ceding crucial territories north of the Aras River and granting Russia considerable economic privileges and extraterritorial rights. These losses exacerbate Persia's internal instability, highlight the declining power of the Qajar Dynasty, and catalyze Armenian migrations into Russian-held territories. Russia introduces new administrative structures, Russian legal systems, and educational reforms in newly acquired territories, significantly impacting local governance and society.

British Maritime Influence and Omani Authority

Said bin Sultan al-Busaidi strengthens Omani trade networks through diplomatic cooperation with Britain. Despite persistent tribal quarrels and the Qawasim pirates' disruptive raids, Said bin Sultan develops a small fleet, secures trade routes, and establishes peace along the Trucial Coast through British-mediated treaties. These agreements stabilize maritime commerce, reinforce British influence, and clearly separate Oman’s coastal governance from the Ibadi interior. Said distances himself from traditional Ibadi authority, adopting the secular title of sultan and solidifying British alliances that safeguard his rule against internal and external threats.

Gulf Tribal Dynamics and Qatar's Ascendancy

In the Persian Gulf, shifting tribal alliances continue to reshape regional politics. The Al Thani clan in Qatar solidifies its control and autonomy, leveraging the weakening power of the Al Khalifa in Bahrain and resisting their attempts to reassert dominance. The Al Thani embrace Wahhabi ideology, reinforcing their distinct religious and political identity. The Bani Yas tribe under the Al Nahyan family further consolidates power in Abu Dhabi, allying themselves strategically with Oman against threats from the Qawasim pirates of the Pirate Coast. Qatar, under the Al Thani, thus emerges increasingly independent, driven by its strategic position and ideological alignment with Wahhabism.

Russian Consolidation in the Caucasus

The Russian Empire further consolidates its hold on the Caucasus, enforcing stricter administrative control and introducing Russian legal and educational systems in Georgia and northern Azerbaijan. Tsar Alexander I's annexation of Kartli-Kakhetia in 1801 and subsequent integration of Imeretia in 1804 significantly disrupt local Georgian feudal structures. The Georgian Orthodox Church loses its autocephalous status in 1811. Russian dominance intensifies following Persia’s defeats, further partitioning Azerbaijani lands into three Russian administrative provinces. The integration of Armenians under a unified legal system under Russian rule facilitates the rise of Armenian national consciousness.

Legacy of the Era

Between 1828 and 1839, the Middle East experiences critical transformations. Egyptian military expansion challenges Ottoman sovereignty, prompting significant international diplomatic interventions. Persian territorial losses and internal fragmentation underline Qajar weaknesses. Saudi-Wahhabi consolidation in Arabia, British maritime dominance in the Gulf, and Russian expansion in the Caucasus collectively reshape regional dynamics, laying crucial foundations for future geopolitical developments.

Mohammad Mirza, heir to the Qajarid throne, is the son of Abbas Mirza, the crown prince and governor of Azerbaijan, who in turn is the son of Fat′h Ali Shah Qajar, the second Shah of the dynasty.

At first, Abbas Mirza had been the chosen heir to the Shah.

However, after he died, the Shah had chosen Mohammad to be his heir.

After the Shah's death, Ali Mirza, one of his many sons, had tried to take the throne in opposition to Mohammad.

After a rule of about forty days, he had been quickly deposed at the hands of Mirza Abolghasem Ghaem Magham Farahani, a politician, scientist, and poet.

Ali is forgiven by Mohammad, who now becomes king of Persia.

Farahani had been awarded the position of prime minister by Mohammad at the time of his inauguration but in 1835 is betrayed and executed by the order of Shah at the instigation of Haji Mirza Aqasi, who becomes the Ghaem Magham's successor and who is to greatly influence the Shah's policies.

One of his wives, Malek Jahan Khanom, Mahd-e Olia, is later to become a large influence on his successor, who is their son.

Russia has expanded in Central Asia, backing Persian ambitions in western Afghanistan, as the British have increased their territory in India.

On November 22, 1837, Persian ruler Mohammed Shah Qajar lays siege to the city of Herat, historically the western gateway to Afghanistan and northern India.

Russian officers provide support and advice to the Iranian army.

Herat is defended by an Afghan garrison, under Yar Mohammed.

The Persians had made an attempt to storm Herat on June 24, 1838, after conducting a somewhat desultory siege, but were repulsed with a loss of seventeen hundred men.

A tacit armistice exists until September 9, 1838, when the Shah withdraws his army.

The defenders of Herat are estimated to have lost about one thousand of their number, while the Persians have lost about two thousand.

The Middle East: 1840–1851 CE

Ottoman Restoration and Egyptian Retreat

The era beginning in 1840 witnesses the restoration of direct Ottoman rule in Syria and Lebanon, following Egyptian withdrawal. The Convention of London (1840) decisively ends the Egyptian occupation, compelling Muhammad Ali Pasha to relinquish his Syrian territories back to the Ottomans while securing hereditary rule over Egypt for his family. Ottoman authorities, aiming to reestablish stability and control, initiate administrative reforms known as the Tanzimat, introducing structured taxation systems and limited modernization in the provinces. However, these reforms face resistance from local elites accustomed to greater autonomy, particularly in Syria and Mount Lebanon.

In Mount Lebanon, Bashir II Shihab pays a heavy price for his earlier allegiance to Egypt. After Egyptian withdrawal, he is deposed in 1840 and exiled, leading to political instability exacerbated by sectarian tensions among Maronites, Druze, and Muslims. Bashir III is appointed amir of Mount Lebanon on September 3, 1840, but bitter conflicts between Christians and Druzes quickly resurface under his rule. These tensions result in Bashir III's deposition on January 13, 1842, replaced by Ottoman governor Umar Pasha. To ease tensions, the Ottoman sultan partitions Lebanon into two districts under separate Christian and Druze deputy governors, known as the Double Qaimaqamate. However, this partition only deepens sectarian animosities, occasionally erupting into violence, notably in May 1845. The European powers intervene, prompting the Ottomans to establish advisory councils (majlis) representing the different religious communities.

Saudi Arabia: Turmoil and British Influence

In Arabia, the Al Saud dynasty under Faisal ibn Turki Al Saud faces intense internal strife following the assassination of his father, Turki ibn Abd Allah, in 1834. Faisal consolidates control from Riyadh by 1843 after nearly a decade of internecine warfare. During this period, Ottoman forces briefly occupy eastern Arabian territories, including Al Qatif and Al Hufuf, exploiting internal Saudi divisions.

Faisal’s reign balances relations with the Ottoman Empire and emerging British interests. Britain's strategic concern over the Persian Gulf, due to trade routes and protection of India, increasingly influences Arabian politics. The British East India Company establishes treaty relations with several Gulf emirates, intensifying British presence and shaping regional political developments. The Al Saud leverage their Wahhabi influence to maintain control over central Arabia, though their influence in the Hijaz remains limited due to Ottoman and Egyptian vigilance.

Persian Decline and Increased Foreign Intervention

In Persia, the Qajar Dynasty struggles with internal instability and external pressures following significant territorial losses to Russia. The aftermath of the Treaty of Turkmanchay (1828) leaves Persia economically and politically weakened, prompting increasing British and Russian interference—the rivalry known as "The Great Game."

Under Mohammad Shah Qajar (1834–1848), central authority erodes, leading to regional uprisings and increased autonomy of tribal leaders. Upon the accession of Naser ad-Din Shah in 1848, his prime minister, Mirza Taqi Khan Amir Kabir, initiates reforms aimed at strengthening central authority, modernizing taxation, encouraging trade and industry, and establishing the Dar ol Fonun school for elites. However, jealousy and political intrigue lead to Amir Kabir's dismissal and execution in 1851, symbolizing the persistent internal weaknesses that allow further foreign intervention.

Oman's Maritime and Diplomatic Expansion

Said bin Sultan al-Busaidi expands Oman's maritime trade, enhancing economic prosperity and international prestige. His rule is characterized by commercial diplomacy, maintaining favorable relations with Britain. Oman's East African territories, particularly Zanzibar, become major trade hubs for spices, ivory, and slaves, solidifying Oman's strategic importance to British interests in securing maritime routes between Europe and India.

Tribal Dynamics in the Gulf and the Rise of Qatar

The Al Thani clan firmly establishes itself in Qatar, asserting independence from the Al Khalifa of Bahrain and resisting external domination attempts. The ideological alignment of the Al Thani with Wahhabism continues distinguishing Qatar politically and religiously from neighboring emirates.

In Abu Dhabi, the Al Nahyan family consolidates power, leveraging alliances with Oman and Britain to secure their territorial claims. The Bani Yas tribe’s alignment further stabilizes Abu Dhabi, ensuring its growth as a regional power.

Russian Consolidation and Cultural Transformation in the Caucasus

The Russian Empire consolidates administrative control over Georgia and northern Azerbaijan, systematically introducing Russian legal, administrative, and educational reforms. Tsar Alexander I had abolished the kingdom of Kartli-Kakhetia in 1801, integrating eastern Georgia and subsequently western Georgia by 1804. Russian rule significantly transforms local societies, fostering a new educated elite influenced by Russian culture and governance. Armenian national consciousness intensifies as Armenians from Russia and former Persian provinces come under unified tsarist administration.

Russia's victory over Persia in 1828 and annexation of the area around Erevan brings thousands of Armenians into the Russian Empire, integrating them within a single legal and administrative framework. The Armenian community benefits from relative peace and economic growth under Russian rule, significantly ending previous isolation.

Legacy of the Era

From 1840 to 1851, the Middle East witnesses major geopolitical reconfigurations marked by Ottoman restoration, Persian decline, and increased British and Russian intervention. The reshaping of state structures, tribal dynamics, and communal identities during this period establishes enduring political frameworks and sectarian divisions, profoundly impacting regional politics and society into the modern era.