Mariano Paredes

15th president of Mexico

Years: 1797 - 1849

Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga (c. 7 January 1797 – 7 September 1849) was a conservative Mexican general and president.

He took power in a coup d'état in 1846.

He was the president at the start of the Mexican-American War.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 18 total

A coalition of Federalists and moderates ousts Antonio López de Santa Anna from the Mexican presidency in December, 1844, and installs Jose Joaquin Herrera as acting president of Mexico in place of the exiled dictator.

Herrera, whose government has already taken British-encouraged steps to recognize the independence of the Republic of Texas, backs off from Santa Anna’s militancy on the Texas Question.

The Centralist factions plot Herrerra’s overthrow.

The Herrera government signals Mexico's willingness to resume relations with the United States in August, 1845, hoping also to finally settle the question of reparations to U.S. citizens for damages incurred during the Mexican War of Independence.

Meanwhile, Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga leads the Centralists, bitterly opposed to the moderate policies pursued by the Herrera government, in beginning to demand an attack on the United States.

President Herrera’s request for a plenipotentiary to Mexico is finally answered in early December by the appearance of John Slidell, whom Polk has authorized to purchase New Mexico and California from Mexico and to settle the disputed Texas boundary.

Herrera, fearful for the safety of his coalition government in highly politicized climate, refuses to meet with him.

Paredes issues a revolutionary manifesto on December 14.

General Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga leads an army into Mexico City on January 2, 1846.

President José Joaquín de Herrera flees and Paredes, assuming the presidency on January 4, expels John Slidell from Mexico.

In November 1845, U.S. president James Polk had sent Slidell, a secret representative, to Mexico City with an offer to the Mexican government of twenty-five million dollars million for the Rio Grande border in Texas and Mexico's provinces of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México.

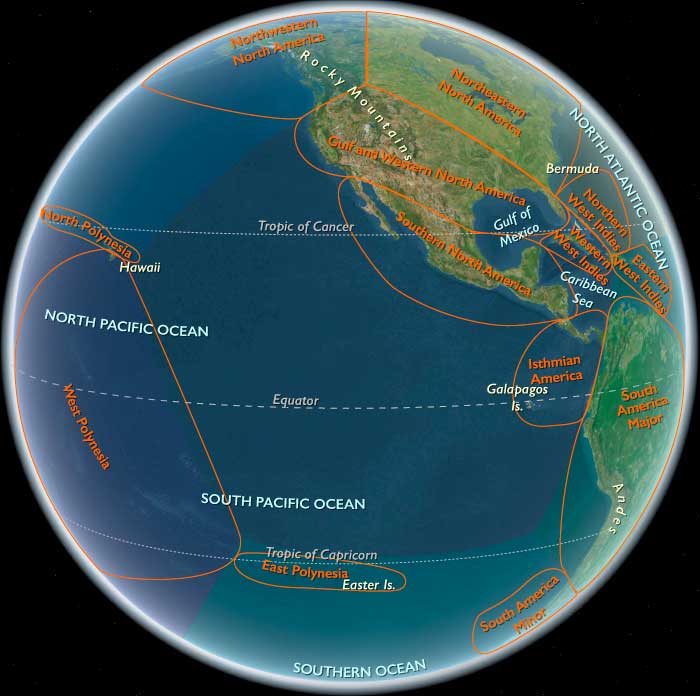

U.S. expansionists want California to thwart British ambitions in the area and to gain a port on the Pacific Ocean.

Polk had authorized Slidell to forgive the three million dollars owed to U.S. citizens for damages caused by the Mexican War of Independence and pay another twenty-five million to thirty million dollars in exchange for the two territories.

Mexico is not inclined nor able to negotiate.

In 1846 alone, the presidency will change hands four times, the war ministry six times, and the finance ministry sixteen times.

Mexican public opinion and all political factions agree that selling the territories to the United States would tarnish the national honor.

Mexicans who oppose direct conflict with the United States, including President José Joaquín de Herrera, are viewed as traitors.

Military opponents of de Herrera, supported by populist newspapers, considered Slidell's presence in Mexico City an insult.

When de Herrera considered receiving Slidell to settle the problem of Texas annexation peacefully, he was accused of treason and deposed.

After a more nationalistic government under General Paredes comes to power, it publicly reaffirms Mexico's claim to Texas; Slidell, convinced that Mexico should be "chastised", returns to the U.S.

The Mexican government’s refusal either to sell its trans-Rio Grande territories or to pay claims for losses sustained by American citizens during Mexico’s War of Independence provides an excuse for President Polk’s clearly stated intentions to annex the Mexican provinces of California and New Mexico, as well as to make the Rio Grande the western border of Texas.

The Paredes-led Centralist government, regarding Texas as Mexican land, mobilizes troops in early 1846 as Paredes reiterates his intention of attacking Texas.

Paredes, confident in the prowess of his well-armed, disciplined, experienced army of about thirty-two thousand men, speaks of occupying New Orleans and Mobile.

Many Centralists count on the abolitionist movement to demoralize the U.S. fighting spirit; some Centralists hope America’s enslaved people will rise in support of a Mexican invasion.

This sparks the "Thornton Affair", an ambush that takes place twenty miles west upriver from Zachary Taylor's camp along the Rio Grande.

The Mexican cavalry routs the patrol, killing eleven American soldiers.

Regarding the beginning of the war, Ulysses S. Grant, who opposes the war serves as an army lieutenant in Taylor's Army, claims in his Personal Memoirs (1885) that the main goal of the U.S. Army's advance from Nueces River to Rio Grande was to provoke the outbreak of war without attacking first, to debilitate any political opposition to the war.

Following the failure of John Slidell’s mission, President Polk had ordered General Zachary Taylor to occupy the territory between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande, which he had done on March 28, 1845.

Abolitionists claim that Polk’s move is a hostile and aggressive act of provocation designed ultimately to gain a new slave territory for the United States.

A few Federalist leaders had contacted Taylor while he while he was camped along the Nueces River in the spring, promising supplies and asking for American support in overthrowing Mariano Paredes.

On April 4, Paredes had ordered his commander at Matamoros to attack Taylor; the commander delayed, Paredes had replaced him, issued a declaration of war on April 23, and reordered the attack.

The Mexicans had crossed the Rio Grande and ambushed a platoon of dragoons on April 25, 1846.

The Americans had quickly repulsed two more attacks at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma on May 8—9, defeats that had surprised and dismayed the Mexican leaders.

Paredes blames his commanding general for the defeat by the outnumbered U.S. force rather than acknowledge the effectiveness of American light artillery.

The Matamoros garrison, with a new commanding general, evacuates to the south.

U.S. forces invade Mexican territory on two main fronts after the declaration of war on May 13, 1846.

The U.S. War Department sends a U.S. Cavalry force under Stephen W. Kearny to invade western Mexico from Jefferson Barracks and Fort Leavenworth, reinforced by a Pacific fleet under John D. Sloat.

This is done primarily because of concerns that Britain might also try to seize the area.

Two more forces, one under John E. Wool and the other under Taylor, are ordered to occupy Mexico as far south as the city of Monterrey.

U.S. General Zachary Taylor, having crossed the Rio Grande with twenty-three hundred troops after some initial difficulties in obtaining river transport, occupies Matamoros on May 18, then digs in to await transportation promised him by the U.S. government.