Juan de Oñate

Spanish explorer and colonial governor

Years: 1552 - 1626

Don Juan de Oñate Salazar (1552–1626) is a Spanish explorer, colonial governor of the New Spain province of New Mexico, and founder of various settlements in the present day Southwest of the United States.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 8 events out of 8 total

They have, moreover, apparently recovered in numbers from the disastrous levies on their resources that Coronado had imposed.

Chamuscado and Rodriguez with their slight numbers make fewer demands on the Pueblos, although they have one altercation after natives kill three Spanish horses.

Chamuscado and Rodriguez visit sixty-one Pueblo towns along the Rio Grande and its tributaries and count a total of seven thousand and three houses of one or more stories in the pueblos.

If all houses were occupied and if a later estimate of eight persons per house is accurate, the population of the towns visited may have been fifty-six thousand people. In addition, they hear of other pueblos, including the Hopi, which they are unable to visit.

The Spanish learn that Friar Juan had been killed by natives only two or three days after leaving the expedition.

Despite the killing of Friar Juan, the two remaining friars are determined to stay in New Mexico.

The soldiers leave them, most of their supplies, and several Indian servants behind in the Tiwa town of Puaray and depart to return to Santa Barbara on June 31, 1582.

Chamuscado, almost seventy years of age, dies during their return journey.

The eight remaining soldiers will arrive in Santa Barbara on April 15, 1582.

The two friars and their native servants left behind are also soon killed by the Tiwa, although two natives had escaped and returned to Mexico to tell the story.

The Chamuscado and Rodriguez expedition had been a modest affair, but revives Spanish interest in New Mexico and will lead to a colony being established here a few years later by Juan de Oñate.

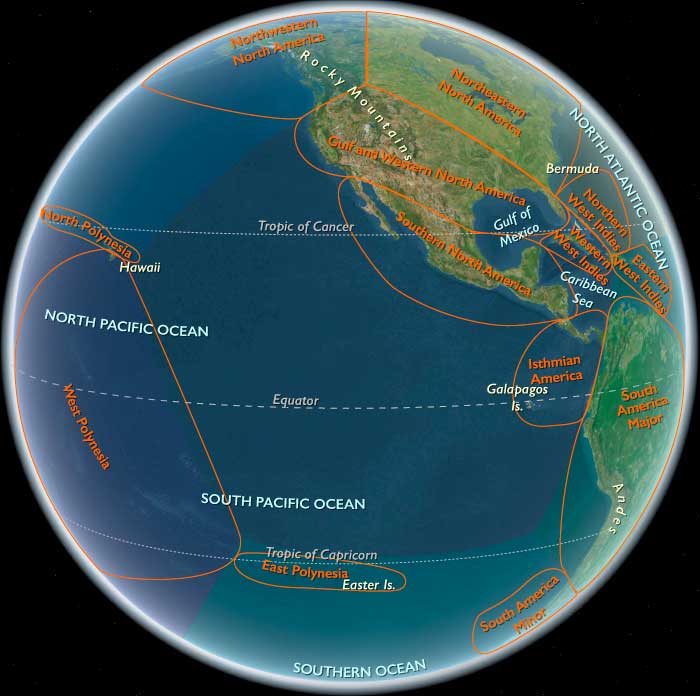

Gulf and Western North America (1588–1599 CE): Spanish Expansion and Indigenous Realignments

Expansion of Spanish Influence

During 1588–1599, the Spanish further solidify their control over strategic locations in Gulf and Western North America. The colony of Santa Fe, formally established in 1598 by Juan de Oñate in northern New Mexico, becomes a pivotal base for Spanish governance, trade, and missionary activity. This new colony enhances Spain’s presence in the Southwest and serves as a center for religious conversion and administration, fundamentally influencing regional indigenous cultures.

Southeastern Cultural Dynamics

In Florida, indigenous societies continue experiencing transformative pressures due to sustained Spanish colonization. Tribes like the Apalachee, Timucua, and Calusa navigate complex relations with the Spanish, ranging from resistance to cautious cooperation. Despite persistent demographic losses due to diseases, these groups maintain significant cultural resilience. The Leon-Jefferson culture (1500–1704), succeeding the Fort Walton culture, continues to adapt agricultural and social systems amid increasing European contact.

Indigenous Adaptations and Challenges

Groups such as the Tequesta, Jaega, and Ais, who had long-established tribal structures, face significant disruptions but continue to thrive by leveraging coastal and marine resources effectively. These indigenous societies show notable resilience, maintaining political autonomy through carefully managed interactions with the Spanish and other indigenous groups.

Early Equestrian Integration in the Southwest

In the Southwest, early integration of horses continues at a modest pace among indigenous groups. The Apache and Navajo enhance their mobility and economic capabilities through gradual equestrian adoption, primarily through trade and occasional raiding of Spanish settlements. The emerging equestrian culture begins to reshape traditional hunting, trade, and warfare practices.

Ecological and Social Stability

Despite ongoing Spanish incursions, indigenous communities across the region demonstrate considerable adaptability. Agricultural systems are maintained and adjusted to changing ecological conditions, while intertribal trade networks remain robust, connecting disparate groups such as the Pensacola, Apalachee, and Timucua.

Key Historical Developments

-

Establishment of Santa Fe colony in 1598, bolstering Spanish administrative and missionary influence in the Southwest.

-

Persistent resilience and adaptation of indigenous groups (Tequesta, Jaega, Ais, Calusa) in Florida despite severe demographic and ecological pressures.

-

Continued incremental adoption and integration of horses by indigenous groups (Apache, Navajo) in the Southwest.

-

Maintenance of agricultural productivity and cultural continuity by indigenous Gulf Coast societies (Leon-Jefferson, Apalachee, Timucua).

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The establishment of Santa Fe marks a significant expansion of Spanish influence in the Southwest, introducing lasting changes in indigenous political and cultural landscapes. In Florida, sustained Spanish presence reinforces a pattern of cautious interaction and selective cultural adaptation among indigenous societies, setting the stage for future demographic and ecological transformations. The slow but steady adoption of equestrian practices by Southwestern indigenous groups begins reshaping regional dynamics, anticipating future social and military shifts.

Juan de Oñate Salazar, ordered by King Philip II in 1595 to colonize the upper Rio Grande Valley (explored in 1540-1542 by Francisco Vásquez de Coronado) and the Chamuscado and Rodriguez Expedition in 1581-1582, begins the expedition in 1598, fording the Rio Grande (Río del Norte) at the present-day Ciudad Juárez–El Paso crossing in late April, and claiming for Spain all of New Mexico beyond the river on the 30th.

Oñate, whose stated objective is to spread Roman Catholicism and establish new missions, had begun his career fighting against the Chichimecs in the northern frontier region of New Spain.

His wife is Isabel de Tolosa Cortés de Moctezuma, granddaughter of Hernán Cortés, the conqueror of the Aztec Triple Alliance, and great granddaughter of the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma Xocoyotzin.

Oñate’s party continues up the Rio Grande in the summer to present-day northern New Mexico, where he encamps among the Pueblo people.

The name Nuevo México had first been used by a seeker of gold mines named Francisco de Ibarra who had explored far to the north of Mexico in 1563 and reported his findings as being in "a New Mexico".

Oñate, who officially establishes the name when he is appointed the first governor of the new province, establishes the San Juan de los Caballeros colony, the first permanent European settlement in the future state of New Mexico, on the Rio Grande near Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo.

Oñate had soon gained a reputation as a stern ruler of both the Spanish colonists and the indigenous people.

A skirmish erupts in October 1598 when Oñate's occupying Spanish military demands supplies from the Acoma tribe—demanding things essential to the Acoma surviving the winter.

The Acoma resist and thirteen Spaniards are killed, among them Don Juan Oñate’s nephew.

Oñate retaliates in 1599: his soldiers kill eight hundred villagers.

They enslave the remaining five hundred women and children, and by Don Juan’s decree, they amputate the left foot of every Acoma man—there are eighty of them—over the age of twenty-five.

Other commentators put the figure of those mutilated at twenty-four.

Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá, a captain of the expedition, will chronicle Oñate’s conquest of New Mexico’s indigenous peoples in his epic Historia de Nuevo México (1610).

Oñate had journeyed east from New Mexico, crossing the Great Plains and encountering two large settlements of people he called Rayados, most certainly Wichita, and Escanjaques, who may be identical with the Aguacane who live along the tributaries of the Red River in western Oklahoma.

If so, they are probably related to the people later known as the Wichita.

The Escanjaques try to persuade Oñate to plunder and destroy "Quiviran" villages.

The Rayado city is probably on the Walnut River near Arkansas City, Kansas.

Oñate describes the city as containing "more than twelve hundred houses" which would indicate a population of about twelve thousand.

His description of the Etzanoa is similar to that of Coronado's description of Quivira.

The homesteads are dispersed; the houses round, thatched with grass and surrounded by large granaries to store the corn, beans, and squash they grow in their fields.

Oñate's Rayados are probably the Wichita sub-tribe later known as the Guichitas.

What the Coronado and Oñate expeditions show is that the Wichita people of the sixteenth century are numerous and widespread.

They are not, however, a single tribe at this time but rather a group of several related tribes speaking a common language.

The dispersed nature of their villages probably indicates that they are not seriously threatened by attack by enemies, although that will change as they will soon be squeezed between the Apache on the West and the powerful Osage on the East.

European diseases will also probably be responsible for a large decline in the Wichita population in the seventeenth century.

Gulf and Western North America (1672–1683 CE): Escalating Tensions and Pathways to Revolt

Intensifying Spanish Pressure in Santa Fe de Nuevo México

The Spanish colony of Santa Fe de Nuevo México further expanded its control over the upper Rio Grande (Río Bravo del Norte) valley. Colonists intensified demands for tribute and forced labor from Pueblo communities, heightening indigenous resentment. The harsh Spanish administration, combined with aggressive missionary activities aimed at suppressing traditional religious practices, created an environment ripe for organized indigenous resistance.

Prelude to the Pueblo Revolt

By the late 1670s, tensions between the Spanish and Pueblo peoples reached a boiling point. Pueblo spiritual leaders, particularly the medicine man Popé, began actively coordinating resistance among multiple Pueblo communities. Despite continued Spanish prohibitions, the Pueblo discreetly expanded their expertise in horse management and utilization, strengthening their potential for coordinated resistance.

Apache Ascendancy and the Expansion of Equestrian Culture

The Apache intensified horse raids during this period, further expanding their territory and military capabilities. These raids severely strained Spanish colonial resources and disrupted Pueblo agricultural production. By 1680, the Apache had firmly established themselves as dominant equestrian warriors, significantly altering regional dynamics and pressing upon the periphery of Spanish colonial settlements.

Ecological and Agricultural Adjustments in the Mississippi Valley

In the Mississippi Valley, indigenous agricultural communities adapted further to the persistent ecological disruptions caused by European-introduced livestock. Tribes like the Caddo continued to refine their methods, enhancing sustainability and food security despite pressures from pigs and cattle. Though impacted by European diseases, these societies maintained a degree of economic and ecological stability.

Indigenous Stability and Autonomy in California

California's coastal societies—the Chumash, Luiseño, and Yokuts—remained insulated from direct Spanish colonial influence, maintaining their maritime economies, trade networks, and cultural continuity. This stability provided a stark contrast to the growing tensions and conflicts occurring farther inland.

Missionary and Demographic Struggles in Florida

In Florida, Spanish missionary efforts among the Apalachee, Timucua, Calusa, and Tequesta continued to reshape indigenous communities profoundly. While these groups increasingly blended Christianity with traditional practices, they also faced demographic decline from disease and periodic raiding pressures from English-supported tribes and settlers north of Florida. The missions struggled to maintain adequate food supplies and native labor for Spanish settlements such as St. Augustine.

Navajo Diplomatic Adaptations and Regional Positioning

The Navajo maintained strategic adaptations, balancing selective livestock raiding with diplomatic engagements. Their careful maneuvering ensured relative stability and resource access, further strengthening their regional influence and preparing them to capitalize on future regional disruptions.

Key Historical Developments

-

Growing resistance among Pueblo communities under leaders like Popé, setting the stage for the imminent Pueblo Revolt.

-

Continued expansion of Apache equestrian capabilities, significantly disrupting Spanish and Pueblo societies.

-

Sustained stability and prosperity among coastal California tribes, notably the Chumash, Luiseño, and Yokuts.

-

Persistent indigenous agricultural and ecological innovations in the Mississippi Valley, particularly by the Caddo.

-

Intensified demographic and social struggles within Florida's indigenous communities, notably the Apalachee, Timucua, Calusa, and Tequesta.

-

Navajo strategic diplomacy and selective raiding maintaining regional stability.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The era from 1672 to 1683 was marked by rising tensions and intensified indigenous strategies of resistance and adaptation across Gulf and Western North America. These dynamics culminated in significant historical events, most notably the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, which dramatically reshaped Spanish-indigenous relations and became a pivotal turning point in the history of indigenous resistance to colonial rule in the region. The period laid the groundwork for further indigenous assertiveness and set the stage for new political, economic, and cultural transformations throughout subsequent decades.