Juan de Grijalva

Spanish conquistador

Years: 1489 - 1527

Juan de Grijalva (born around 1489 in Cuéllar, Crown of Castille - January 21, 1527 in Nicaragua) is a Spanish conquistador, and relation of Diego Velázquez.

He goes to Hispaniola in 1508 and to Cuba in 1511.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 21 total

Pánfilo de Narváez, born in Castile (in either Cuéllar or Valladolid) in 1478, is a relative of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, the first Spanish governor of Cuba.

Clergyman Bartolomé de las Casas described him as "a man of authoritative personality, tall of body and somewhat blonde inclined to redness".

Narváez, who had taken part in the Spanish conquest of Jamaica in 1509, had gone to Cuba in 1511 to participate in the conquest of this island under the command of Velázquez de Cuéllar, leading expeditions to the eastern end of the island in the company of las Casas and Juan de Grijalva.

Las Casas observes a number of massacres initiated by the invaders as the Spanish sweep over Cuba, notably the massacre near Camagüey of the inhabitants of Caonao.

As reported by las Casas, who was an eyewitness, Narváez presided over the infamous massacre of Caonao, where Spanish troops put to the sword a village full of some three thousand Indians who had come to Manzanillo meet them with offerings of loaves, fishes and other foodstuffs.

Following the massacre of the Indians, who were "without provocation, butchered", Narváez asks de las Casas, "What do you think about what our Spaniards have done?" to which de las Casas replies, "I send both you and them to the Devil!"

The discovery of the Mayan city the conquistadors call El Gran Cairo, in March 1517, is a crucial moment in the Spanish perception of the natives of the Americas: until then, nothing had resembled the stories of Marco Polo, or the promises of Columbus, which had prophesied Cathay, or even the Garden of Paradise, just past every cape or river.

Even more than the later encounters with the Aztec and Inca cultures, El Gran Cairo resembles the conquistadors' dreams.

When the news arrives in Cuba, the Spaniards create fantasies about the origin of the people they had encountered, whom they refer to as "the Gentiles" or imagine to be "the Jews exiled from Jerusalem by Titus and Vespasian".

All of this encourages two further expeditions: the first in 1518 under the command of Juan de Grijalva, and the second in 1519 under the command of Hernán Cortés, which lead to the Spanish exploration, military invasion, and ultimately settlement and colonization known as the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire and subsequent Spanish colonization in present-day Mexico.

Hernández does not live to see the continuation of his work; he dies in 1517, the year of his expedition, as the result of the injuries and the extreme thirst suffered during the voyage and disappointed in the knowledge that Diego Velázquez, governor of Cuba, had given precedence to his relative Juna de Grijalva as the captain of the next expedition to Yucatán.

The following day, as promised, the natives return with more canoes, to transfer the Spaniards to land.

They are alarmed that the shore is full of natives, and that consequently the landing might prove to be dangerous.

Nonetheless, they land as they are asked to by their until-now friendly host, the cacique (chief) of El Gran Cairo, deciding however to land en masse using also their own launches as a precaution.

It also appears they armed themselves with crossbows and muskets (escopetas); "fifteen crossbows and ten muskets", if we credit the remarkably precise memory of Bernal Díaz del Castillo.

The Spaniards' fears are almost immediately confirmed.

The chief had prepared an ambush for the Spaniards as they approached the town.

They are attacked by a multitude of Indians, armed with pikes, bucklers, slings (Bernal says slings; Diego de Landa denies that the Indians of Yucatán were familiar with slings; he says they threw stones with their right hand, using the left to aim; but the sling was known in other parts of Mesoamerica, and the testimony of those at whom the stones were aimed seems worth crediting), arrows launched from a bow, and cotton armor.

Only the surprise resulting from the effectiveness of the Spaniards' weapons—swords, crossbows, and firearms—puts the more numerous Indians to flight, and allows the Spaniards to re-embark, having suffered the first injuries of the expedition.

as a result of which at least two soldiers will die.

During this battle of Catoche two things occur that are to greatly influence future events.

The first is the capture of two Indians, taken back on board the Spanish ships.

These individuals, who once baptized into the Roman Catholic faith, will receive the names Julianillo and Melchorejo (anglicized to Julián and Melchior), will later become the first Maya language interpreters for the Spanish, on Juan de Grijalva's subsequent expedition.

The second originates from the curiosity and valor of the cleric González, chaplain of the group, who having landed with the soldiers, undertakes to explore—and plunder—a pyramid and some adoratorios while his companions are trying to save their lives.

González has the first view of Maya idols and he brings away with him pieces "half of gold, and the rest copper", which in all ways will suffice to excite the covetousness of the Spaniards of Cuba upon the expedition's return.

After the soldiers return to the ships, the navigator Antón de Alaminos imposes slow and vigilant navigation, moving only by day, because he is certain that Yucatán is an island.

The stores of potable water casks and jugs are not of the quality required for long voyages ("we were too poor to buy good ones", laments Bernal); the casks are constantly losing water and they also fail to keep it fresh, so de Córdoba's ships need to replenish their supplies ashore.

The Spaniards have already noted that the region seems to be devoid of freshwater rivers.

Fifteen days after the battle at Catoche, the expedition lands to fill their water vessels near a Maya village they call Lázaro (after St Lazarus' Sunday, the day of their landing; "The proper Indian name for it is Campeche", clarifies Bernal).

Once again they are approached by Indians appearing to be peaceable, and the now-suspicious Spaniards maintain a heavy guard on their disembarked forces.

During an uneasy meeting, the local Indians repeat a word (according to Bernal) that ought to have been enigmatic to the Spaniards: "Castilan".

This curious incident of the Indians apparently knowing the Spaniards' own word for themselves they will later attribute to the presence of the shipwrecked voyagers of de Nicuesa's unfortunate 1511 fleet.

Unknown to de Córdoba's men, the two remaining survivors, Jerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, are living only several days' walk from the present site.

The Spaniards will not learn of these two men until the expedition of Hernán Cortés, two years later.

The Spaniards find a solidly built well used by the Indians to provide themselves with fresh water, with which they are invited fill their casks and jugs.

The Indians, again with friendly aspect and manner, bring them to their village, where once more they can see solid constructions and many idols (Bernal alludes to the painted figures of serpents on the walls, so characteristic of Mesoamerica).

They also meet their first priests, with their white tunics and their long hair impregnated with human blood.

This is the end of the Indians' friendly conduct: they convoke a great number of warriors and order them to burn some dry reeds, indicating to the Spaniards that if they aren't gone before the fire goes out, they will be attacked.

Hernández's men decide to retreat to the boats with their casks and jugs of water before the Indians can attack them, leaving safely behind them the discovery of Campeche.

Hernán Cortés, born to low Spanish nobility in Medellin, Extremadura, had attended the University of Salamanca at age fourteen, abandoned his studies after two years, and, after a few years of wandering, sailed in 1504 at nineteen to Santo Domingo to seek his fortune in the New World.

Cortés had reached Hispaniola in a ship commanded by Alonso Quintero, who tried to deceive his superiors and reach the New World before them in order to secure personal advantages.

Quintero's mutinous conduct may have served as a model for Cortés in his subsequent career.

The history of the conquistadores is rife with accounts of rivalry, jockeying for positions, mutiny, and betrayal.

Upon his arrival in Santo Domingo, the capital of Hispaniola, the eighteen-year-old Cortés had registered as a citizen, which entitled him to a building plot and land to farm.

Soon afterwards, Nicolás de Ovando, still the governor, gave him an encomienda and made him a notary of the town of Azua de Compostela.

His next five years seemed to help establish him in the colony; in 1506, Cortés had taken part in the conquest of Hispaniola and Cuba, receiving a large estate of land and Indian slaves for his efforts from the leader of the expedition.

In 1511, Cortés had accompanied Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, an aide of the Governor of Hispaniola, in his expedition to conquer Cuba.

Velázquez had been appointed as governor.

Cortés, then twenty-six, had been made clerk to the treasurer with the responsibility of ensuring that the Crown received the quinto, or customary one fifth of the profits from the expedition.

Velázquez, was so impressed with Cortés that he secured a high political position for him in the colony.

He became secretary for Velázquez and was twice appointed municipal magistrate (alcalde) of Santiago.

In Cuba, Cortés had become a man of substance with an encomienda to provide Indian labor for his mines and cattle.

This new position of power had also made him the new source of leadership, to which opposing forces in the colony could now turn.

In 1514, Cortés had led a group that demanded that more Indians be assigned to the settlers.

Cortés also finds time to become romantically involved with Catalina Xuárez (or Juárez), the sister-in-law of Governor Velázquez.

Part of Velázquez's displeasure seems to have been based on a belief that Cortés was trifling with Catalina's affections.

Cortés is temporarily distracted by one of Catalina's sisters but finally marries Catalina, reluctantly, under pressure from Governor Velázquez.

However, by doing so, he hopes to secure the good will of both her family and that of Velázquez.

It is not until he has been almost fifteen years in the Indies that Cortés begins to look beyond his substantial status as mayor of the capital of Cuba and as a man of affairs in the thriving colony.

He has missed the first two expeditions, under the orders of Francisco Hernández de Córdoba and then Juan de Grijalva, sent by Diego Velázquez to Mexico in 1517 and 1518, respectively.

The importance given to the news, objects, and people that Hernández had brought to Cuba can be gleaned from the speed with which the following expedition has been prepared.

The governor Diego Velázquez places his nephew Juan de Grijalva, who has his complete confidence, in charge of this second expedition.

The news that this "island" of Yucatán has gold, doubted by Bernal but enthusiastically maintained by Julianillo, the Maya prisoner taken at the battle of Catoche, feeds the subsequent series of events that is to end with the Conquest of Mexico by the third flotilla sent, that of Hernán Cortés.

Governor Velázquez provides all four ships, in an attempt to protect his claim over the peninsula.

The small fleet is stocked with crossbows, muskets, barter goods, salted pork and cassava bread.

According to Hernán Cortés, one hundred and seventy people traveled with Grijalva, but according to the court historian Peter Martyr there were three hundred people.

The principal pilot is Antón de Alaminos; the other pilots are Juan Álvarez, Pedro Camacho de Triana, and Grijalva.

Other members include Francisco de Montejo, who will eventually conquer much of the peninsula, Pedro de Alvarado, Juan Díaz, Francisco Peñalosa, Alonso de Ávila, Alonso Hernández, Julianillo, Melchorejo, and Antonio Villafaña.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo serves on the crew; he is able to secure a place on the expedition as a favor from the governor, who is his kinsman.

They embark from the port of Matanzas, Cuba, with four ships in April 1518.

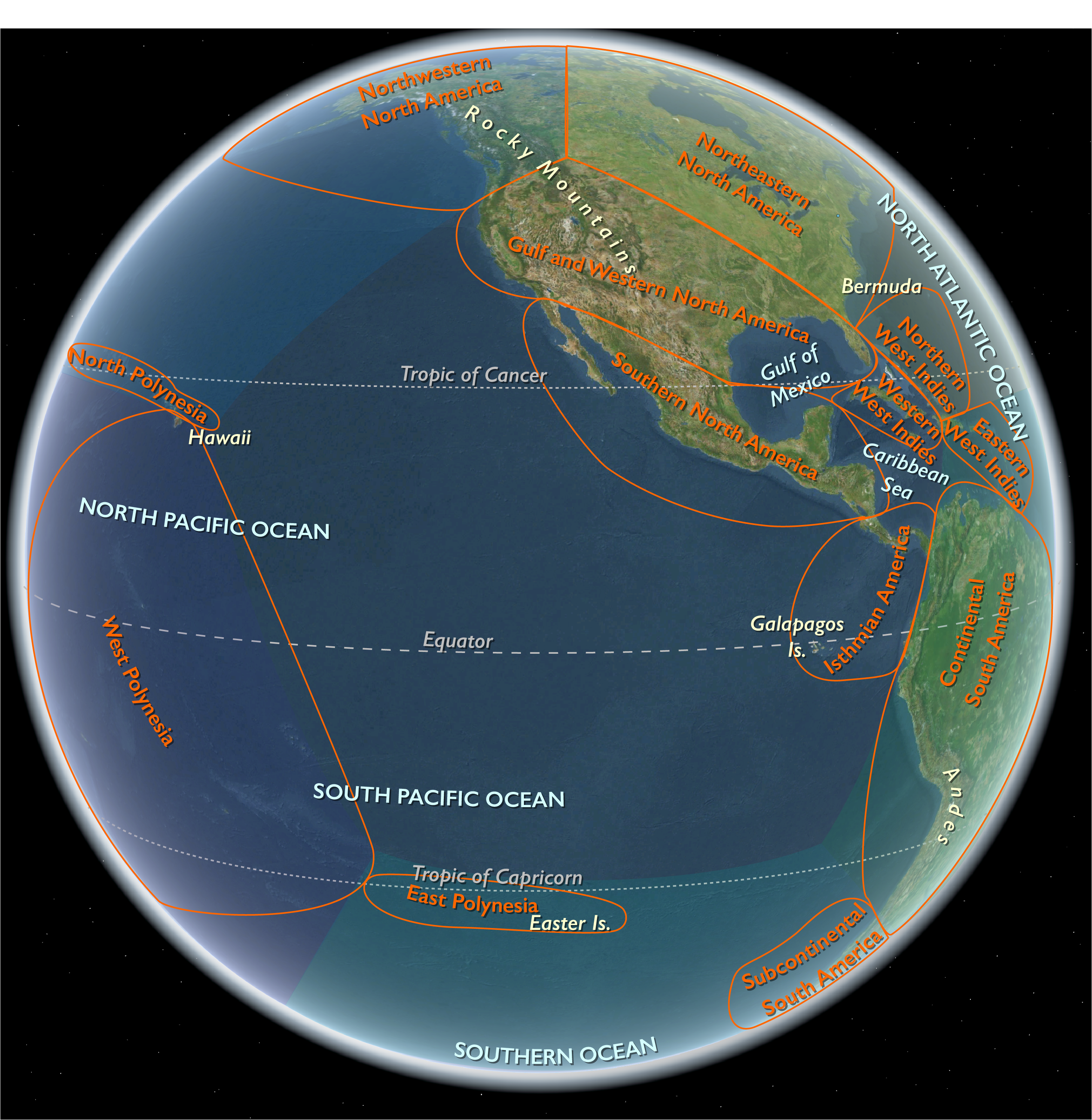

Juan de Grijalva, after rounding the Guaniguanico in Cuba, sails along the Mexican coast and discovers Cozumel.

The Maya inhabitants flee the Spanish and will not respond to Grijalva's friendly overtures.

The Maya are believed to have first settled Cozumel by the early part of the first millennium CE, and older Preclassic Olmec artifacts have been found on the island as well.

The island is sacred to Ix Chel, the Maya Moon Goddess, and the temples here are a place of pilgrimage, especially by women desiring fertility.

There are today a number of ruins on the island, most from the Post-Classic period.

The largest Maya ruins on the island are near the downtown area and have now been destroyed.

Today, the largest remaining ruins are at San Gervasio, located approximately at the center of the island.

The fleet sails south from Cozumel, along the east coast of the peninsula.

The Spanish spot three large Maya cities along the coast, one of which is probably Tulum, a busy Maya commercial center with dazzling white buildings.

On Ascension Thursday the fleet discovers a large bay, which the Spanish name Bahía de la Ascensión.

Grijalva does not land at any of these cities and turns back north from Ascensión Bay.

Looping around the north of the Yucatán Peninsula to sail down the west coast, at Campeche the Spanish try to barter for water but the Maya refuse, so Grijalva opens fire against the city with small cannon; the inhabitants flee, allowing the Spanish to take the abandoned city.

Messages are sent with a few Maya who had been too slow to escape but the Maya remain hidden in the forest.

The Spanish boards their ships and continue along the coast.

The fleet is approached by a small number of large war canoes at Champotón, where the inhabitants had routed Hernández and his men, but the ships' cannon soon puts them to flight.