João Rodrigues Cabrilho

Portuguese explorer in the service of Spain

Years: 1499 - 1543

João Rodrigues Cabrilho (ca.

1499 – January 3, 1543), Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in Spanish, is a Portuguese explorer noted for his exploration of the west coast of North America on behalf of Spain.

Cabrillo is the first European explorer to navigate the coast of present day California in the United States.

He helps found the city of Oaxaca, in Mexico.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 10 total

Spanish arms are introduced into what is now the United States in the southeast by Hernando de Soto and in the southwest by Francisco Coronado.

The expeditions led by the two conquistadors encounter many native peoples new to Europeans, leaving a path of military destruction and biological devastation in their wake, but fail to find the gold sought by every conquistador since Cortes and Pizarro.

The main material impact of the Spaniards is the introduction of the horse to southwest and the pig to the southeast.

Juan Cabrillo, aka João Cabrilho, leads the first reconnaissance of the Pacific Coast a few years later.

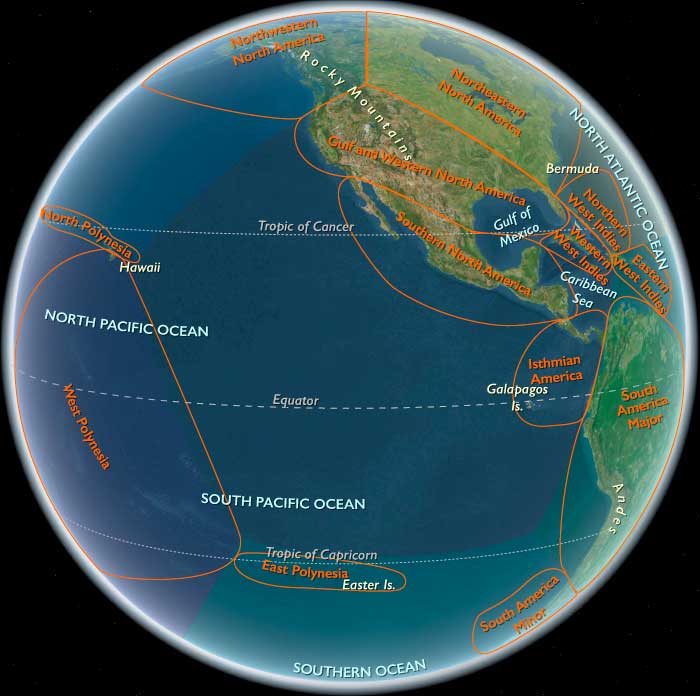

Gulf and Western North America (1540–1551 CE): Spanish Exploration and Indigenous Transformations

Initial Spanish Contact and Consequences

The early 1540s mark significant Spanish exploration in North America, notably through expeditions led by Hernando de Soto in the Southeast and Francisco Coronado in the Southwest. These expeditions introduce European warfare, disease, and domestic animals to indigenous populations. Though failing to discover anticipated riches, the Spanish presence initiates profound biological and cultural transformations among native peoples.

Southeastern Indigenous Societies

In Florida and the southeastern regions, Spanish explorers encounter densely populated agricultural societies such as the Apalachee, Timucua, Tocobaga, and Calusa peoples. The arrival of Europeans triggers catastrophic epidemics, significantly reducing these populations and disrupting their societal structures. Although these groups initially resist Spanish dominance, the spread of European livestock—particularly pigs introduced by de Soto—alters local ecological conditions.

Southwestern Indigenous Responses

In the Southwest, Coronado’s expedition impacts groups such as the Puebloan peoples, whose established agricultural villages begin to interact closely with the Spanish. The introduction of horses, initially controlled strictly by the Spanish, will later significantly transform regional cultures. By 1550, the mobile Apache and Navajo peoples are aware of these new animals, though widespread equestrian culture does not fully develop until later decades.

The Patayan culture of western Arizona, characterized by mobile lifestyles and modest settlements, experiences increasing pressure and environmental challenges around 1550, ultimately disappearing for uncertain reasons, possibly due to flooding and climatic stress.

Florida’s Complex Societies

Florida’s indigenous societies, shaped by millennia of ecological adaptation, experience dramatic changes with Spanish arrival. The rich estuarine environments sustain complex societies such as the Tequesta, Jaega, Ais, and Calusa. Although these established tribes do not immediately succumb to direct Spanish control, their exposure to European diseases begins a period of severe demographic decline.

In northern Florida and the panhandle region, the Pensacola and the succeeding Leon-Jefferson culture (which directly replaced the Fort Walton culture after 1500), with their maize agriculture and mound-building traditions, encounter profound disruptions. The arrival of European livestock, along with epidemics and sporadic violence, significantly reshapes their traditional lifeways.

Key Historical Developments

-

Expeditions of Hernando de Soto and Francisco Coronado introducing European animals and diseases.

-

Severe demographic and cultural impacts on southeastern societies such as the Apalachee and Timucua.

-

Initial, limited introduction of horses in the Southwest, altering future indigenous mobility.

-

Disappearance of the Patayan culture around 1550.

-

Early impact on Florida's indigenous cultures, particularly through disease and ecological changes introduced by European contact.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The years 1540–1551 represent a turning point for indigenous societies in Gulf and Western North America, initiating profound demographic, cultural, and ecological transformations. These initial encounters set the stage for centuries of interaction, conflict, adaptation, and resistance between indigenous peoples and European settlers.

Juan Cabrillo, or João Cabrilho, a Portuguese navigator employed by Spain, has taken part in the Spanish conquest of Mexico and Guatemala.

He had joined the exploring voyage of Pedro de Alvarado up the west coast of Mexico in 1540 in search of the legendary Seven Golden Cities of Cibola.

Having assumed command of the California coastal expedition after the death of Alvarado, Cabrilho had sailed north from Navidad in 1542.

He is probably the first European to see California, putting in at San Diego Bay, naming it San Miguel, in September 1542, ...

...before continuing past San Francisco Bay, which he does not see.

Cabrilho also sights Santa Catalina Island (which he names San Salvador) and ...

...Point Reyes, and ...

...enters Monterey Bay...

Cabrilho, having suffered a broken leg while landing on one of the coastal islands, dies on San Miguel Island in the Santa Barbara Channel on January 3, 1543, apparently of complications from the injury.

Bartoloméo Ferrer, João Cabrilho’s successor in command, leads the Spanish expedition north in the spring of 1543, to a point just short of the present border of Oregon and California.

The two ships, battered by tremendous seas, barely make it back to Mexico.

Gulf and Western North America (1672–1683 CE): Escalating Tensions and Pathways to Revolt

Intensifying Spanish Pressure in Santa Fe de Nuevo México

The Spanish colony of Santa Fe de Nuevo México further expanded its control over the upper Rio Grande (Río Bravo del Norte) valley. Colonists intensified demands for tribute and forced labor from Pueblo communities, heightening indigenous resentment. The harsh Spanish administration, combined with aggressive missionary activities aimed at suppressing traditional religious practices, created an environment ripe for organized indigenous resistance.

Prelude to the Pueblo Revolt

By the late 1670s, tensions between the Spanish and Pueblo peoples reached a boiling point. Pueblo spiritual leaders, particularly the medicine man Popé, began actively coordinating resistance among multiple Pueblo communities. Despite continued Spanish prohibitions, the Pueblo discreetly expanded their expertise in horse management and utilization, strengthening their potential for coordinated resistance.

Apache Ascendancy and the Expansion of Equestrian Culture

The Apache intensified horse raids during this period, further expanding their territory and military capabilities. These raids severely strained Spanish colonial resources and disrupted Pueblo agricultural production. By 1680, the Apache had firmly established themselves as dominant equestrian warriors, significantly altering regional dynamics and pressing upon the periphery of Spanish colonial settlements.

Ecological and Agricultural Adjustments in the Mississippi Valley

In the Mississippi Valley, indigenous agricultural communities adapted further to the persistent ecological disruptions caused by European-introduced livestock. Tribes like the Caddo continued to refine their methods, enhancing sustainability and food security despite pressures from pigs and cattle. Though impacted by European diseases, these societies maintained a degree of economic and ecological stability.

Indigenous Stability and Autonomy in California

California's coastal societies—the Chumash, Luiseño, and Yokuts—remained insulated from direct Spanish colonial influence, maintaining their maritime economies, trade networks, and cultural continuity. This stability provided a stark contrast to the growing tensions and conflicts occurring farther inland.

Missionary and Demographic Struggles in Florida

In Florida, Spanish missionary efforts among the Apalachee, Timucua, Calusa, and Tequesta continued to reshape indigenous communities profoundly. While these groups increasingly blended Christianity with traditional practices, they also faced demographic decline from disease and periodic raiding pressures from English-supported tribes and settlers north of Florida. The missions struggled to maintain adequate food supplies and native labor for Spanish settlements such as St. Augustine.

Navajo Diplomatic Adaptations and Regional Positioning

The Navajo maintained strategic adaptations, balancing selective livestock raiding with diplomatic engagements. Their careful maneuvering ensured relative stability and resource access, further strengthening their regional influence and preparing them to capitalize on future regional disruptions.

Key Historical Developments

-

Growing resistance among Pueblo communities under leaders like Popé, setting the stage for the imminent Pueblo Revolt.

-

Continued expansion of Apache equestrian capabilities, significantly disrupting Spanish and Pueblo societies.

-

Sustained stability and prosperity among coastal California tribes, notably the Chumash, Luiseño, and Yokuts.

-

Persistent indigenous agricultural and ecological innovations in the Mississippi Valley, particularly by the Caddo.

-

Intensified demographic and social struggles within Florida's indigenous communities, notably the Apalachee, Timucua, Calusa, and Tequesta.

-

Navajo strategic diplomacy and selective raiding maintaining regional stability.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The era from 1672 to 1683 was marked by rising tensions and intensified indigenous strategies of resistance and adaptation across Gulf and Western North America. These dynamics culminated in significant historical events, most notably the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, which dramatically reshaped Spanish-indigenous relations and became a pivotal turning point in the history of indigenous resistance to colonial rule in the region. The period laid the groundwork for further indigenous assertiveness and set the stage for new political, economic, and cultural transformations throughout subsequent decades.