Jim Bridger

American mountain man, trapper, scout and guide

Years: 1804 - 1881

James Felix "Jim" Bridger (March 17, 1804 – July 17, 1881) is among the foremost mountain men, trappers, scouts and guides who explore and trap the Western United States during the decades of 1820-1850, as well as mediating between native tribes and encroaching whites.

He is of English ancestry, and his family has been in North America since the early colonial period.

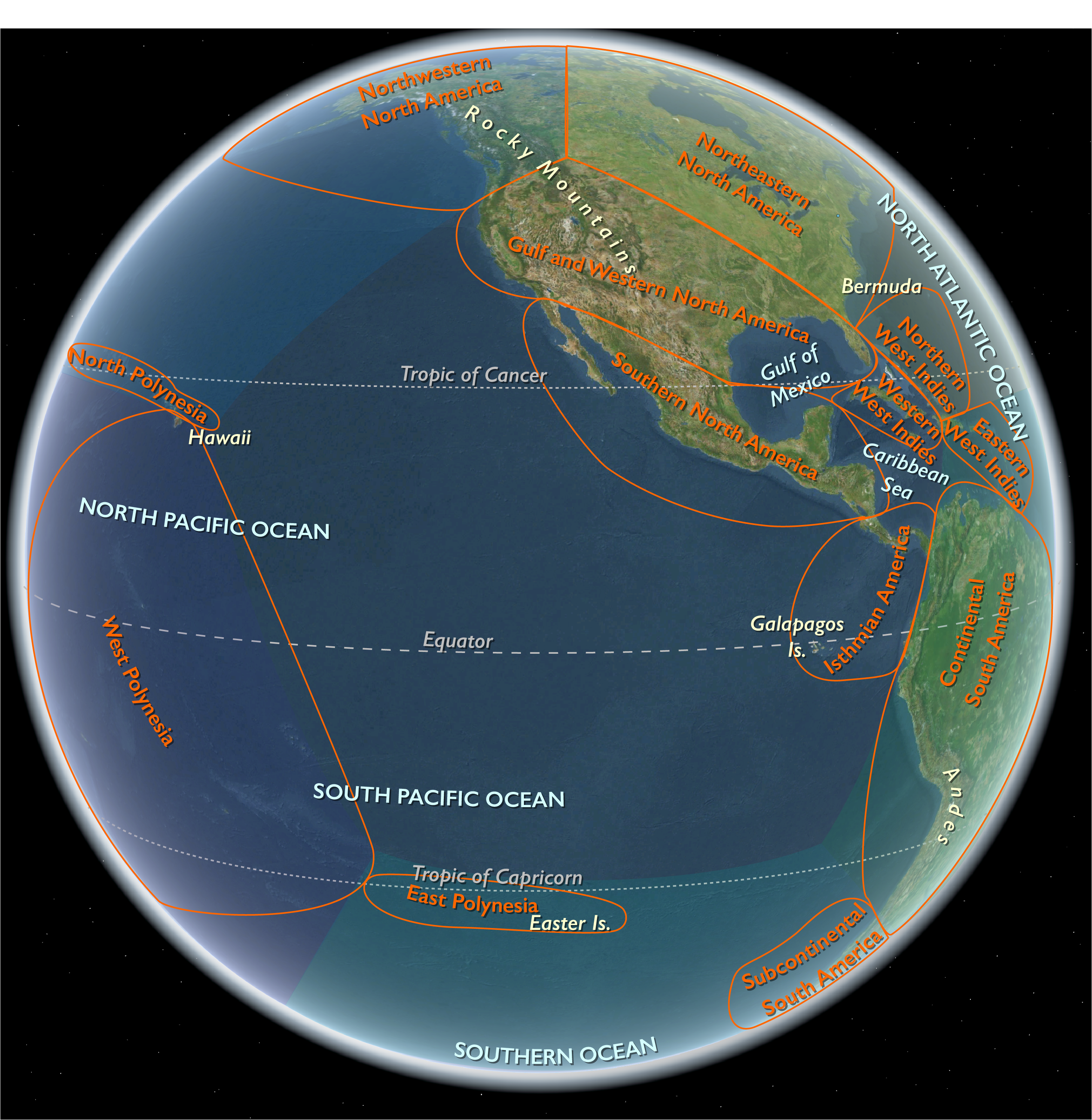

Jim Bridger has a strong constitution that allows him to survive the extreme conditions he encounters walking the Rocky Mountains from what will become southern Colorado to the Canadian border.

He has conversational knowledge of French, Spanish and several native languages.

He comes to know many of the major figures of the early west, including Brigham Young, Kit Carson, George Armstrong Custer, John Fremont, Joseph Meek, and John Sutter.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 15 total

William Henry Ashley, recently the lieutenant governor of Missouri, joins Andrew Henry—a bullet maker he had met through his gunpowder business—in posting advertisements in St. Louis newspapers seeking one hundred "enterprising young men . . . to ascend the river Missouri to its source, there to be employed for one, two, or three years."

The men who responded to this call will become known as "Ashley's Hundred."

Twenty-three year old Jedediah Strong Smith, originally of western New York, is a member of Ashley’s party.

Ashley, although born a native of Powhatan County, Virginia, had already moved to Ste. Genevieve, in what was then a part of the Louisiana Territory, when it was purchased by the United States from France in 1803.

On a portion of this land, later known as Missouri, Ashley had made his home for most of his adult life.

Ashley had moved to St. Louis around 1808 and became a Brigadier General in the Missouri Militia during the War of 1812.

Before the war, he had done some real estate speculation and earned a small fortune manufacturing gunpowder from a lode of saltpeter mined in a cave, near the headwaters of the Current river in Missouri.

When Missouri was admitted to the Union, Ashley had been elected its first Lieutenant Governor, serving, from 1820 under Governor Alexander McNair.

When Lewis and Clark reached Arikara settlements in 1804, the inhabitants had not shown hostility to the expedition, but in 1806, when an Arikara leader died during a trip to the United States capital, many Arikara believed that Americans were involved in his death.

Eventually, as a result of the growing activity of fur trading companies, contact between Arikara and white merchants had become more frequent, and skirmishes eventually followed.

The Sioux, both Yankton and Yanktonai east of the Missouri and Lakota on the west side, have for long been at war with the Arikara, interrupted by short truces on Sioux terms.

The Arikaras in question are living in a double village on the west shore of the Missouri, six or seven miles upstream from the mouth of Grand River.

A small creek separates the two fortified villages of earth lodges, each with a heavy frame of wood.

The surviving trappers retreat down the river and hide in shelters, where they will stay for more than a month.

A fictionalized representation of the 1823 attack by the Arikara on the Rocky Mountain Fur Company appears in the 2015 film The Revenant from the perspective of trapper Hugh Glass.

The seven hundred and fifty warriors are part Yankton and Yanktonai Sioux, part western Sioux from the Brule, the Blackfeet and the Hunkpapa divisions.

The native force receives promises of Arikara horses and spoils, and with the enemy's villages fallen new ranges will open for the Sioux.

The Arikara live in permanent settlements for most of the year where they farm, fish and hunt buffalo on the surrounding plains.

However, this is insufficient to sustain them and they rely on being a center of trade with neighboring tribes to survive.

Ashley's expedition to directly acquire furs and pelts cuts out the Arikara in their role as trading middle-men and is thus a direct threat to their livelihood.

There is also the issue of their desire to have a trading post on their territory so that they can have easy access to manufactured goods.

They resent the fact that their long-time enemies, the Sioux, have such posts, but they do not.

Ashley had been asked to set up a trading post when he was in the area in 1822.

Not wishing to limit his operations by having to maintain a permanent base, Ashley had instead promised the Arikara that he would have the goods they asked for shipped to them directly from St. Louis.

Ashley had not made good this promise at the time of his 1823 expedition, and possibly never intended to.

A further source of resentment, although probably not a direct cause of the war, had been the death of the Arikara chief Ankedoucharo during a visit to Washington in 1806.

Ankedoucharo had died of natural causes, but it was widely believed among the Arikara that he was deliberately murdered.

The initial episode at the Arikara villages on June 2 reaches international level when some hinted, that the British Hudson's Bay Company is the mastermind behind it all.

The plot, so some believe, is to put a wedge between the American fur traders and the Arikaras.

The British deny this.

On August 10 Leavenworth orders an artillery bombardment.

This is largely ineffective, the shots falling beyond the villages, at which point Leavenworth orders an infantry attack.

Like the Sioux auxiliaries, the regular infantry also fails to break into the villages.

They leave the battlefield with some captured horses and laden with corn taken from the farming Indians' fields.

On August 11 Leavenworth negotiates a peace treaty.

"In making this treaty, I met with every possible difficulty which it was in the power of the Missouri Fur Company to throw in my way."

Fearing further attacks, the Arikara leave the village that night.

Leavenworth sets off to return to Fort Atkinson on August 15.

The Arikara village is burned behind him by resentful members of the Missouri Fur Company, much to Leavenworth's anger.

The US Army suffers the first casualties in the West during the Arikara War; seven people drown in the Missouri.

Major General Grenville M. Dodge orders the Powder River expedition as a punitive campaign against the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho.

It is led by Brigadier General Patrick E. Connor.

Dodge orders Connor to "make vigorous war upon the Indians and punish them so that they will be forced to keep the peace." (Hampton, H.D. "The Powder River Expedition 1865" Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Autumn 1964)).

The Connor expedition is one of the last Indian war campaigns carried out by U.S Volunteer soldiers.

One of Connor's guides is the legendary frontiersman Jim Bridger, who in the previous year had blazed the Bridger Trail, an alternate route from Wyoming to the gold fields of Montana that avoided the dangerous Bozeman Trail.

Connor's strategy is for three columns of soldiers to march into the Powder River Country.

The "Right Column" is composed of fourteen hundred Missouri soldiers, mostly mounted, led by Colonel Nelson Cole.

It marches from Omaha, Nebraska and is to follow the Loup River in Nebraska westward to the Black Hills and meet up with Connor near the Powder River.

The "Center Column" of six hundred men is commanded by Samuel Walker of the 16th Kansas Cavalry and is to head north from Fort Laramie and traverse the country west of the Black Hills.

The "Left Column" of six hundred and seventy-five men is composed of the 6th Michigan Volunteer Cavalry Regiment under Colonel James H. Kidd, recently transferred from the Civil War battlefields of Virginia.

This command includes ninety-five Pawnee and eighty-four Omaha scouts and a wagon train full of supplies with one hundred and ninety-five civilian teamsters.

General Connor will personally accompany Kidd's column and will move along the Powder River with the goal of establishing a fort near the Bozeman Trail.

All three columns are to unite at the new fort.

Connor's orders to his commanders are, "You will not receive overtures of peace or submission from Indians, but will attack and kill every male Indian over twelve years of age."

Connor's superiors, Generals Pope and Dodge, attempt to countermand this order, but too late, as Connor's expedition has already departed and is out of contact.

Colonel Cole had left Omaha on July 1 with his fourteen hundred men and one hundred and forty wagon-loads of supplies.

Following the Loup River upstream, they had gone cross country to Bear Butte, near present day Sturgis, South Dakota, arriving there on August 13.

Cole hadn't see a single native during the five hundred and sixty-mile (nine hundred kilometer-) march, but his command had suffered from thirst, diminishing supplies, and near mutinies.

Colonel Walker and his six hundred men had left Fort Laramie on August 6 and meet up with Cole on August 19 near the Black Hills.

He had likewise encountered no natives and had suffered from shortages of water.

The two columns march separately, but remain in contact as they move westward to the Powder River.

By this time the men are barefoot and horses and mules are dying—and they have still not encountered any natives.

General Connor and Colonel Kidd and their six hundred and seventy-five soldiers, native scouts, and teamsters had left Fort Laramie on August 2 to unite with the commands of Cole and Walker.

Proceeding northward, they established a fort on the upper Powder River which is named Fort Connor.

On August 16, Major Frank North and the Pawnee scouts discover a native trail, follow it, attack a group of twenty-four Cheyenne warriors, and kill them all.

A few days later, North has his horse shot from under him by Cheyennes but is rescued by the Pawnee.

The Battle of the Tongue River is the most significant engagement of the Powder River Expedition.

Connor marches north from Fort Connor and on August 28 Frank North and his Pawnee scouts find an Arapaho village of about six hundred people on the Tongue River near present day Ranchester, Wyoming.

Connor sends in two hundred soldiers with two howitzers and forty Omaha and Winnebago and thirty Pawnee scouts, and march that night toward the village. (The Pawnee, Omaha, and Winnebago tribes are traditional enemies of the Arapaho and their Cheyenne and Lakota allies.)

With mountain man Jim Bridger leading the forces they charge the village, whose leader is Black Bear.

The people in the village are primarily women, children, and old men, as most of the warriors are absent, engaged in a war with the Crow on the Bighorn River.

The few warriors present at the camp put up a strong defense and cover the women and children as most escape beyond the reach of the soldiers and Indian scouts.

The surprised natives flee the village, but regroup and counterattack and Connor is dissuaded from pursuing them.

The battle is a U.S. victory, resulting in sixty-three Arapaho dead, mostly women and children.

After the battle the soldiers burn and loot the abandon tipis and capture eight women and thirteen children, who are subsequently released.

The Pawnee make off with the five hundred horses from the camp's herd as payback for previous raids by the Arapaho.

Connor, who singles out four Winnebago, including chief Little Priest, plus North and fifteen Pawnee for bravery, claims to have killed thirty-five Arapaho warriors, a total probably exaggerated, at a cost to his force of five dead.

Connor now turns around and returns to Fort Connor, harassed en route by the Arapaho.

The Arapaho, who had not been overtly hostile before, now join the Sioux and Cheyenne.