Jean Laborde

adventurer and early industrialist in Madagascar

Years: 1805 - 1878

Jean Laborde (16 October 1805 in Auch – 27 December 1878 in Mantasoa, Madagascar) was an adventurer and early industrialist in Madagascar. He became the chief engineer of the Merina monarchy, supervising the creation of a modern manufacturing center under Queen Ranavalona I. Later he became the first French consul to Madagascar, when the government of Napoleon III used him to establish French influence on the island.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 4 events out of 4 total

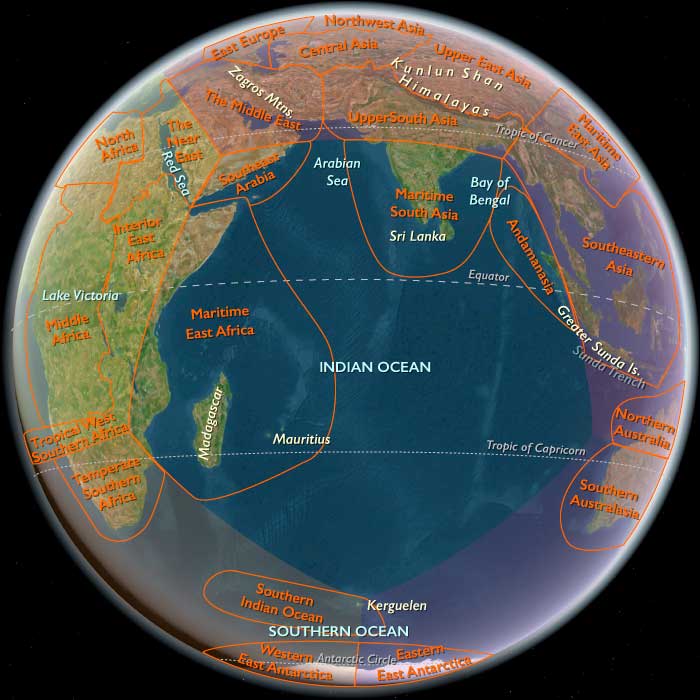

Maritime East Africa (1828–1839 CE): Abolition, Social Transformation, and Political Reaction

From 1828 to 1839 CE, Maritime East Africa—including Mauritius, Seychelles, Madagascar, and the Swahili Coast—undergoes pivotal transformations marked by the abolition of slavery, profound social restructuring, significant missionary influence, and complex political dynamics.

Mauritius: Abolition of Slavery and Economic Transition

In Mauritius, plantation owners of French origin (Franco-Mauritians) have vigorously resisted British efforts to abolish slavery. Nevertheless, under sustained British pressure, slavery is finally abolished in 1835. To appease the powerful planter class, the British government grants substantial concessions, including financial compensation totaling £2.1 million and enforced "apprenticeship" for former enslaved persons, compelling them to remain on plantations for another six years.

However, widespread desertions among the so-called apprentices create a severe labor shortage, forcing authorities to abandon the apprenticeship system in 1838, two years ahead of schedule. This abrupt shift dramatically reshapes the island's economy, leading to increased reliance on indentured laborers from India in subsequent decades.

Seychelles: Post-Abolition Migration and Cultural Integration

In the Seychelles, slavery is abolished in 1834, triggering a significant demographic and social shift. Many impoverished European settlers leave the islands, taking their former slaves with them. Subsequently, the British navy brings in large numbers of liberated Africans, rescued from slave ships intercepted along the East African coast, dramatically altering the islands’ demographic makeup.

The arrival of small groups of traders from China, Malaysia, and India adds to this diversity, with these groups primarily engaging in commerce. A pattern of extensive intermarriage among African, European, and Asian populations emerges (with the notable exception of the Indian community), creating a highly mixed society. By 1911, racial classifications become effectively meaningless due to this extensive integration and are ultimately abandoned.

Madagascar: Radical Reform and Conservative Backlash

In Madagascar, Radama I (r. 1810–1828) had significantly modernized and centralized the island’s administration, inviting Protestant missionaries from the London Missionary Society to establish schools, introduce the printing press, and devise a written form of the local language (Malagasy), using the Latin alphabet. By 1828, thousands of Merina individuals had become literate, and a select few students traveled to Britain for education. These efforts dramatically reshape the cultural landscape, fostering the development of a literate Merina elite and widespread Protestant conversion.

The accession of Queen Ranavalona I (r. 1828–1861) marks a stark shift. Reacting strongly against foreign influence, Ranavalona I's reign is characterized by isolationism, persecution of Protestant converts, and stringent control over trade. Many Europeans flee, although a privileged few, such as the French artisan Jean Laborde, continue to enjoy special favor. Laborde establishes a significant manufacturing complex at Mantasoa, near Antananarivo, producing silk, soap, guns, tools, and cement, highlighting a paradoxical embrace of limited modernization within a broadly reactionary political framework.

Swahili Coast: Omani Influence and Local Resistance

On the Swahili Coast, Omani control remains robust, notably under Sultan Sa'id bin Sultan, who asserts his authority firmly against local resistance—especially in strategically important cities like Mombasa and islands such as Zanzibar and Pemba. British naval forces temporarily intervene (1824–1826) on behalf of Oman but eventually withdraw. Continued local resistance, notably from the Mazrui dynasty, persists, reflecting sustained tension between Omani rulers and indigenous populations.

Malawi and Mozambique:

In the early nineteenth century, southern Malawi sees the establishment of missionary settlements, particularly the Scottish-founded town of Blantyre (named after the birthplace of explorer David Livingstone). These missions introduce new economic and agricultural practices, gradually transforming regional socioeconomic patterns. Meanwhile, central and northern Mozambique continue under Portuguese influence, their coastal settlements serving as pivotal hubs for trade in ivory, gold, and enslaved people, maintaining regional economic significance amid growing European imperial interests.

Legacy of the Age

The period from 1828 to 1839 CE in Maritime East Africa is marked by significant social and political transformations: the end of institutional slavery profoundly reshapes economic structures in Mauritius and Seychelles, triggering demographic and cultural shifts. Madagascar experiences dramatic swings between progressive modernization and conservative isolationism, profoundly influencing its political and social trajectory. The Swahili Coast continues its complex interplay between Omani dominance and resilient local identities, setting the stage for further colonial and imperial contests in the coming decades.

Maritime East Africa (1852–1863 CE): British Influence, Economic Expansion, and Madagascar's Political Shifts

From 1852 to 1863 CE, Maritime East Africa—including the Somali coast, Mauritius, and Madagascar—experiences expanding British influence, significant economic developments tied to global markets, and notable political shifts within Madagascar’s Merina kingdom.

Somali Coast: Local Rule and British Relations

In 1854–1855, British naval lieutenant Richard Burton explores the northern Somali coast, observing significant local political autonomy despite formal foreign influences. At Saylac, Burton encounters Somali governor Haaji Sharmarke Ali Saleh of the Habar Yoonis clan, who exerts practical authority over the city and its surroundings. However, Saylac itself has significantly declined from its former prominence, now characterized by crumbling infrastructure, ineffective water storage, and recurrent incursions by local tribal groups.

Farther east along the Majeerteen (Bari) coast, two influential Somali kingdoms emerge prominently: the Majeerteen Sultanate under Boqor Osman Mohamoud, and the Sultanate of Hobyo (Obbia) under Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid. Sultan Osman Mohamoud’s leadership sees considerable economic growth from trading in livestock, ostrich feathers, and gum arabic, enhanced by British subsidies intended to protect British shipwreck survivors along the Somali coastline. Although nominally acknowledging British influence, these Somali kingdoms maintain considerable autonomy well into the nineteenth century.

Mauritius: Sugar Dominance under British Rule

In Mauritius, sugar production becomes the island’s dominant economic sector, significantly shaping its colonial economy under British administration. Initially incentivized by Britain’s decision in 1825 to equalize sugar duties across colonies, Mauritius dramatically expands its sugar output. From 1825 to 1826, production nearly doubles, and by 1854, the island surpasses one hundred thousand tons annually. Between 1855 and 1859, Mauritius achieves its peak significance as Britain’s primary sugar-producing colony, contributing 9.4 percent of the global sugar supply.

Despite rising overall production through subsequent decades, Mauritius’s global sugar dominance gradually diminishes due to declining world sugar prices and intensified competition from other sugar-producing nations. Nevertheless, the concentration on sugar transforms the island’s economy, diminishing food-crop cultivation and reinforcing large, plantation-based landholdings.

Madagascar: Political and Diplomatic Fluctuations under Merina Rule

Madagascar’s political environment undergoes significant swings during this era. Under King Radama II (r. 1861–1863), Madagascar adopts a notably pro-European stance, particularly toward France. Radama II signs a treaty of perpetual friendship with France, signifying openness to Western influence and modernization. However, his policies quickly provoke opposition from conservative nobles alarmed by the increasing French presence.

In 1863, Radama II is assassinated by nobles opposed to his pro-French diplomacy, abruptly ending his short reign. His widow, Queen Rasoherina (r. 1863–1868), succeeds him, swiftly reversing his policies. She annuls the French treaty and dissolves agreements made by Radama II, including revoking the charter of the influential French entrepreneur Jean Laborde, whose ventures had significantly shaped Madagascar’s industrial and agricultural landscape.

Malawi and Mozambique:

The mid-nineteenth century witnesses increased Portuguese administrative presence in central and northern Mozambique, though practical control remains patchy beyond coastal enclaves. Mozambique’s Zambezi Valley becomes a crucial artery for trade, linking inland southern Malawi settlements, including expanding missionary bases, to coastal markets. Blantyre grows steadily, influenced by increasing missionary activity and early plantation economies introduced by European settlers, setting foundations for its future status as Malawi’s commercial and administrative hub.

Legacy of the Era

The period from 1852 to 1863 CE in Maritime East Africa is marked by expanding British influence along the Somali coast, economic prosperity driven by sugar cultivation in Mauritius, and dramatic political and diplomatic shifts within Madagascar’s Merina kingdom. These developments profoundly shape regional dynamics, setting a foundation for intensified European colonial interactions and economic transformations in subsequent decades.

Maritime East Africa (1864–1875 CE): Regional Power Struggles, Portuguese Ambitions, and Madagascar's Modernization Efforts

From 1864 to 1875 CE, Maritime East Africa experiences intensified internal political rivalries, renewed Portuguese colonial ambitions, and significant social reforms and diplomatic balancing in Madagascar under Merina rule.

Somali Sultanates: Civil Strife and Political Fragmentation

The Somali Sultanate under Boqor Ismaan Mahamuud suffers severe internal strife due to a prolonged power struggle with his cousin, the ambitious Sultan Yuusuf Ali Keenadiid. This destructive civil war lasts nearly five years, severely weakening the sultanate. Ultimately, Boqor Ismaan prevails, forcing Keenadiid into exile in Arabia. Despite Ismaan's victory, the conflict leaves the sultanate fragmented and vulnerable.

Portuguese Colonial Expansion and Ambitions

Portugal significantly renews its colonial ambitions in East Africa during this period, driven in large part by the establishment of the Lisbon Geographical Society in 1875, founded by Portuguese industrialists, scholars, and colonial and military officials. The society fosters popular interest in Africa, prompting increased government investment in colonial infrastructure and missionary activities.

In pursuit of a contiguous colonial territory across central Africa, Portugal launches an ambitious expedition in the late 1870s designed to connect Angola on the Atlantic coast with Mozambique on the Indian Ocean. Although the Portuguese government supports this venture enthusiastically, its ambitions exceed practical capabilities, ultimately failing to secure effective control over the desired interior territories.

Madagascar: Diplomatic Maneuvering and Social Modernization

In Madagascar, Rainilaiarivony effectively governs after 1868, seeking to balance competing British and French interests to avoid direct foreign intervention. He skillfully employs diplomatic tactics, signing significant commercial treaties with France in 1868 and Britain in 1877, while cautiously modernizing Malagasy society.

Under Rainilaiarivony, Madagascar experiences meaningful social reforms, notably the abolition of polygamy and the slave trade, the establishment of new legal codes, and expanded access to education—especially among the Merina population. In a strategic cultural and diplomatic shift, the Malagasy monarchy converts officially to Protestantism in 1869, aligning closer to British interests and reflecting the increasing influence of Protestant missionaries.

Malawi and Mozambique:

Southern Malawi, notably Blantyre, experiences significant transformations with the arrival of additional Scottish missions under the leadership of figures like Reverend David Clement Scott. These missions actively promote education, Christianity, and Western agriculture. Meanwhile, central and northern Mozambique, particularly the Beira Corridor and surrounding areas, attract heightened Portuguese interest, leading to expanded settlement, plantations, and intensified labor extraction practices, deeply embedding these regions into Portugal’s colonial economic framework.

Legacy of the Era

From 1864 to 1875 CE, Maritime East Africa is shaped by internal power struggles in the Somali sultanates, reinvigorated Portuguese colonial ambitions, and Madagascar’s calculated diplomatic balancing combined with notable social reform efforts. These dynamics set the stage for further European intervention and the complex interplay of local and colonial powers in subsequent decades.

Maritime East Africa (1876–1887 CE): European Exploration, Somali Power Shifts, and Colonial Expansion

From 1876 to 1887 CE, Maritime East Africa experiences intensified European exploration and colonization efforts, significant shifts in local political power in Somalia, and deepening European rivalry over strategic island territories and coastal regions.

Portuguese Expeditions into the African Interior

In 1877, Portugal launches a significant scientific expedition from Luanda, led by naval officers Hermenegildo Capelo and Roberto Ivens, accompanied by army major Alexandre Serpa Pinto. The group travels into Angola's interior to the Bié plateau, where they split:

-

Serpa Pinto explores the headwaters of Angola's Cuanza River and follows the Zambezi River to Victoria Falls, eventually crossing the Transvaal and reaching Natal in 1879.

-

Later, in 1884–1885, Capelo and Ivens traverse previously unexplored territories from the coast of Angola (Mocamades) to Quelimane on Mozambique's east coast.

-

Simultaneously, Serpa Pinto and Augusto Cardoso conduct expeditions around Lake Nyassa, significantly enhancing Portuguese geographical knowledge of Mozambique’s interior.

Establishment of German East Africa

In the early 1880s, German adventurer Carl Peters actively seeks colonial acquisitions. After securing treaties with native chiefs opposite Zanzibar, the Society for German Colonization is granted an imperial charter by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck on February 27, 1885. Upon the Sultan of Zanzibar's protest, Bismarck swiftly dispatches a German naval squadron that compels the Sultan's acquiescence, establishing German control over Bagamoyo, Dar es Salaam, and Kilwa.

Return and Rise of Sultan Yuusuf Ali Keenadiid in Somalia

In the 1870s, exiled Somali leader Sultan Yuusuf Ali Keenadiid returns from Arabia with a small contingent of Hadhrami fighters and loyal followers. Utilizing force and strategic alliances, he establishes the new Somali kingdom of Hobyo, subduing local Hawiye clans. Keenadiid’s emergence marks a significant shift in Somali power dynamics, though his rule, along with the neighboring Majeerteen Sultanate, faces increasing pressure from advancing European colonial interests.

European Competition for Somali Territories

The latter part of this era sees intensified European colonial ambitions in Somalia, driven by strategic interests:

-

Britain actively expands its influence from 1884, motivated by the need to secure the northern Somali coast as a supply base (livestock and provisions) for its crucial naval port at Aden, vital for the defense of British India. Major A. Hunter negotiates protection treaties with Somali clans, and British vice-consuls are installed in Berbera, Bullaxaar, and Saylac.

-

Italy, seeking colonial expansion, increasingly pushes into southern Somalia, setting the stage for future colonial consolidation.

French Influence in the Comoros

France, already established in Comoros, gradually extends its influence across the archipelago. Although progress is slow, fueled by persistent internal conflicts among local sultans and rivalry with British and German ambitions, France finally secures protectorate agreements with the rulers of Njazidja, Nzwani, and Mwali in 1886. These agreements set the foundation for the eventual formal annexation and administration of Comoros as part of the French colony of Madagascar in the early twentieth century.

Malawi and Mozambique

Portuguese expeditions like those of explorers Serpa Pinto, Capelo, and Ivens underscore increased colonial ambitions across central and northern Mozambique, emphasizing the economic importance of trade routes through Quelimane and the Zambezi Valley. Southern Malawi (Nyasaland) becomes formally a British protectorate in 1889, with Blantyre established as an administrative and commercial capital, firmly integrating Malawi into Britain’s broader colonial framework in East Africa.

Legacy of the Era

Between 1876 and 1887 CE, Maritime East Africa witnesses transformative European exploration, aggressive colonial expansion, strategic shifts in Somali political power, and deepening European rivalries. These complex interactions set the stage for profound regional changes in the late nineteenth century, significantly impacting local autonomy, trade networks, and sociopolitical structures.