Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville

French Canadian colonizer and colonial adminstrator

Years: 1680 - 1767

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville (February 23, 1680 – March 7, 1767) is a colonizer, born in Montreal, Quebec and an early, repeated governor of French Louisiana, appointed four separate times during 1701-1743.

He was a younger brother of explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville.

He is also known as Sieur de Bienville.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 58 total

Jacques-Rene de Brisay de Denonville, Marquis de Denonville, replaces Joseph Antoine de LaBarre as Governor of New France in 1685, and sets out to make King Louis XIV proud.

The Iroquois Confederation has been a nuisance for half a century, hampering New France's efforts to establish itself as a profitable colony.

A peace treaty was signed in 1667, but the war is renewed in the 1680.

Although France and England are at peace, Denonville sends the newly arrived Pierre de Toyes, the Chevalier de Troyes, north from Montreal with a hundred men (most likely the Troupes de la marine), ...

...to capture the English fur trading posts on the Hudson Bay.

Among his officers are three Le Moyne brothers; Pierre, Jacques and Paul.

They are divided into three groups and head to their destination using the interior waterways.

They capture Moose Factory, ...

...Fort Rupert, and ...

...Fort Albany, leaving Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville in charge of the captured forts.

The victory is swift and profitable.

De Troyes returns to Quebec; word of the French attack will not reach the English for months.

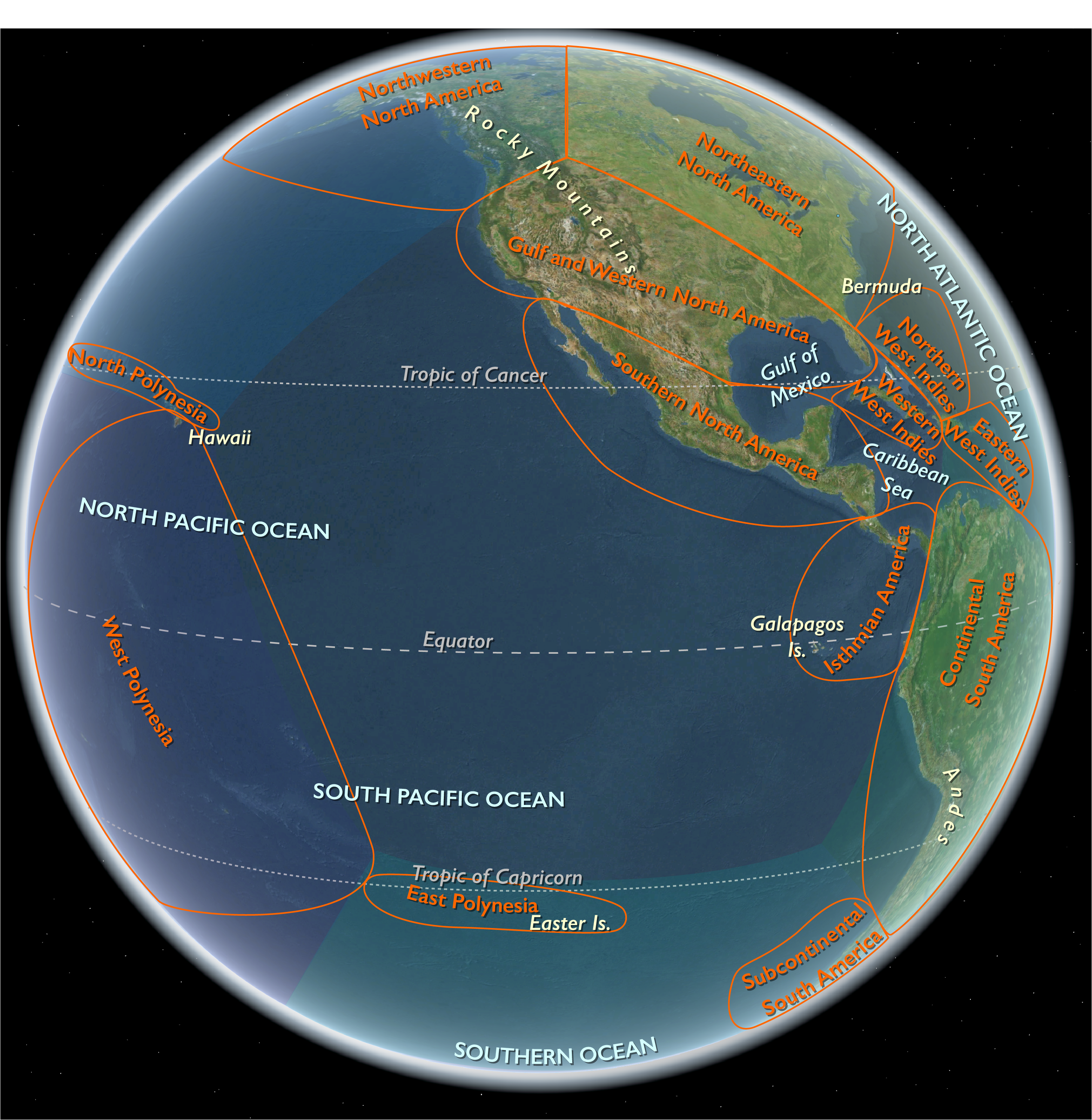

Gulf and Western North America (1696–1707 CE): Indigenous Migrations, Colonial Expansion, and Cultural Exchange

Indigenous Peoples and Horse Culture on the Plains

By the late seventeenth century, diverse indigenous groups occupied distinct ecological niches across the Great Plains. The Algonquian-speaking Blackfeet, having migrated from the forests north of Lake Winnipeg, and the Uto-Aztecan-speaking southern Shoshone—who would become known as the Comanches after migrating from around Utah’s Great Salt Lake—were the only non-agricultural groups in this expansive region.

Agricultural tribes including the Mandan and Hidatsa had established semi-permanent villages along the Missouri River. Other Plains agriculturists, notably ancestors of the Caddo, Wichita, Pawnee, and the Arikara (the latter having recently diverged from the Pawnee), maintained village-based agriculture while gradually adopting the emerging equestrian culture.

Kiowas, primarily residing in northern Texas, Oklahoma, and eastern New Mexico, facilitated the spread of equestrian culture by trading horses to the Wichita, and later to the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples. Similarly, the Utes traded horses to the Wyoming-based Shoshoni, who then passed these horses on to the recently separated Absaroke (Crow) and tribes of the southern Columbia Plateau, including the Nez Perce, Cayuse, and Palouse.

French and Spanish Colonial Rivalries

European claims in North America intensified, with France, Spain, and England consolidating their territories and competing fiercely. French explorers, notably Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, joined his brother Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville to establish the colony of Louisiana. In 1699, they explored the Gulf of Mexico coast, discovering the Chandeleur Islands, Cat Island, and Ship Island, eventually ascending the Mississippi River to present-day Baton Rouge and False River.

Iberville founded the colony's first settlement, Fort Maurepas (present-day Ocean Springs, Mississippi), appointing Sauvolle de la Villantry as governor and Bienville as his lieutenant. Following Iberville’s return to France, Bienville established Fort de la Boulaye in 1700 on the Mississippi River and assumed governance after Sauvolle's death in 1701, initiating the first of his four terms as governor of Louisiana.

In response, Spain reinforced its Gulf Coast presence by establishing a garrison at Pensacola in 1696, setting the foundation for Florida's future capital. Meanwhile, in present-day New Orleans, natives had already established a critical portage between the Mississippi River and Bayou St. John (Bayouk Choupique), leading into Lake Pontchartrain. The integration of native and French settlements around this strategic portage laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the city of New Orleans, a pivotal economic and cultural hub.

Cultural and Religious Encounters in the Lower Mississippi Valley

French Catholic missionaries arrived among the lower Mississippi tribes, including the Taensa, Tunica, and Natchez, around 1699. These tribes, maintaining advanced agricultural societies and sophisticated ceremonial traditions, lived in significant villages featuring large structures often described by Europeans as earth-walled buildings, likely constructed of wattle-and-daub and cane mats.

The Taensa, noted for hierarchical social structures and complex religious practices involving ceremonial sacrifice, experienced devastating losses from European-introduced smallpox around 1700. Continuous raids by the Yazoo and Chickasaw, seeking captives for the English slave trade, further pressured the Taensa, who eventually relocated southwards and became embroiled in conflicts with other indigenous groups, including the Bayogoula and Houma.

Similarly, the French established missions among the Tunica and neighboring tribes (Koroa, Yazoo, Mosopelea) near the mouth of the Yazoo River around 1700. These tribes were distinctive for their complex religious practices and economic roles as middlemen in salt trade between Caddoan groups and the French settlers. During this era, the Chickasaw intensified slave raids, significantly impacting the Tunica, Taensa, and Quapaw populations along the lower Mississippi.

English-Spanish Conflicts in Florida

The early years of Queen Anne’s War saw intense English-Spanish rivalries, notably the English capture and burning of the Spanish town of St. Augustine, Florida in 1702. Although the main fortress withstood English assault, the surrounding settlement suffered extensive damage, marking the campaign as an English military failure. However, these hostilities devastated the Spanish mission system in Florida, culminating tragically in the Apalachee Massacre of 1704, effectively decimating the Apalachee tribe and destabilizing Spanish influence in the region.

Formation and Migration of the Crow Tribe

A distinct group from the Hidatsa villages along the Knife and Heart Rivers (present-day North Dakota) migrated westward between 1675 and 1700. Settling along the lower Yellowstone River in present-day Montana, these "proto-Crow" established initial residences primarily in tipis, indicating early stages of their transformation into a buffalo-hunting society. The Crow maintained connections and cultural exchanges with neighboring tribes such as the Kiowa and Arapaho, with whom they shared significant ceremonial practices and sacred objects, including the powerful Tai-may figure central to the Kiowa Sun Dance.

Key Historical Developments

-

French establishment of the Louisiana colony and early settlements (Fort Maurepas, Fort de la Boulaye).

-

Spanish response through fortified settlements at Pensacola.

-

Cultural and religious exchanges and conflicts among indigenous tribes in the Lower Mississippi Valley.

-

Intensification of slave raids and intertribal conflicts triggered by European demand.

-

English-Spanish military confrontations severely impacting Florida's indigenous communities and Spanish colonial infrastructure.

-

Formation and migration of the Crow tribe and cultural exchanges among Plains tribes.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The era 1696–1707 marked intensified European rivalries, indigenous cultural adaptations, and significant demographic shifts due to disease, warfare, and slave raiding. These developments critically reshaped the sociopolitical landscape, laying the foundations for subsequent European territorial claims and indigenous responses across Gulf and Western North America.

Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, joins the French naval campaigns against the English in the North Atlantic and Hudson Bay in 1695.

At the age of eighteen, Bienville joins his elder brother Pierre Le Moyne d’ Iberville on an expedition to establish the colony of Louisiana.

Bienville and Iberville during this expedition explore the north-central Gulf of Mexico coastline, discovering the Chandeleur Islands off the coast of Louisiana as well as Cat Island and Ship Island off the coast of what is now the state of Mississippi before moving westward to sail up the mouth of the Mississippi River all the way to what is now Baton Rouge and False River.

Before heading back to France, Iberville establishes the first settlement of the Louisiana colony, Fort Maurepas in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, and appoints Sauvolle de la Villantry as the governor and Bienville as Lieutenant and second in command.

Bienville takes another expedition up the Mississippi River following Iberville's departure, and has an encounter with English ships at what is now known as English Turn.

Iberville, upon hearing of this encounter on his return, orders Bienville to establish a settlement along the Mississippi River at the first solid ground he can find.

Bienville establishes Fort de la Boulaye in 1700, fifty miles upriver,.

Bienville ascends to the governorship of the new territory after Sauvolel's death in 1701 for the first of four terms.

The Taensa, who live in seven villages along the Mississippi River south of the Tunica, near the Yazoo River, are visited in 1699, by French Catholic missionaries, who settle among the Taensa, Tunica people, and Natchez.

The Taensa are an agricultural and canoeing people who live in large houses described as having walls of earth.

It is more probable that these were made of wattle and daub structures roofed with mats of woven cane splits.

Their chiefs have absolute power and are treated with great respect.

This varies greatly from the custom among the northern tribes.

The chief, during a ceremonial visit to La Salle, was reported to have been accompanied by attendants who swept the road in front of him with their hands as he advanced.

The missionaries note the complex religion of the Taensa tribe, which has retained chiefdom characteristics after they had disappeared elsewhere.

Their society has similarity to the Natchez people in its practice of sacrificial rites and hierarchical social classes.

Their chief deities seem to have been the Sun and the Serpent.

Their dome-shaped temple is surmounted by the figures of three eagles facing the rising sun, the outer walls and the roof being of cane mats painted entirely red.

The whole is surrounded with a palisade of stakes, on each of which is set a human skull, the remains of a former sacrifice.

Inside is an altar, with a rope of human scalp locks, and a perpetual fire guarded day and night by two old priests.

When a chief dies, his wives and personal attendants are killed so that their spirits might accompany him to the other world.

At one chief's funeral, thirteen victims are sacrificed.

When a Catholic priest stops one of these ceremonies, the temple is struck by lightning.

The Taensa take this as evidence that their beliefs are valid.

The lightning encourages women to volunteer to be sacrificed.

The Spanish expedition of 1540 had only been in the Central Mississippi Valley for a short time but the Spanish presence had had devastating effects.

A favorite tactic of the expedition had been to play off local political rivalries, causing more conflict.

More significantly, the introduction of Eurasian infectious diseases would have ravaged the native population, who had no acquired immunity.

The Central Mississippi Valley by the time the French arrive in 1699 is sparsely occupied by the Quapaw, a Dhegiha Siouan people hostile to the Tunica.

The Tunica and Koroa have relocated further south to the mouth of the Yazoo River in west central Mississippi in the intervening century-and-a-half since the de Soto Expeditio.

The French establish a mission among the Tunica around the year 1700, on the Yazoo River near the Mississippi River in the present-day state of Mississippi.

Archaeological evidence suggests that they had recently migrated to the region from eastern Arkansas, in the late seventeenth century.

Father Antoine Davion is assigned as the missionary for the Tunica as well as the smaller tribes of the Koroa, the Yazoo, and Couspe (or Houspe) tribes.

Unlike the northern tribes with which the French are familiar, the Tunica (and the nearby Taensa and Natchez) have a complex religion.

They have built temples, created cult images, and have a priestly class.

The Tunica, Taensa, and Natchez retain chiefdom characteristics, such as a complex religion and, in the case of the Natchez, the use and maintenance of platform mounds, after they had disappeared elsewhere.

Several characteristics link the Tunica to groups encountered by de Soto: their emphasis on agriculture; cultivation by men rather than women (as de Soto noted when describing Quizquiz); trade; and manufacture and distribution of salt, a valuable item to both native and Europeans.

The trade in salt is an ancient profession among the Tunica, as evidenced by de Soto's noting salt production when visiting the village of Tanico.

Salt is extremely important in the trade between the French and the various Caddoan groups in northwestern Louisiana and southwestern Arkansas.

Scholars believe the Tunica were middlemen in the movement of salt from the Caddoan areas to the French.

By the early eighteenth century, the Chickasaw raid the tribes along the lower Mississippi River to capture people for the English slave trade in South Carolina.

They take an estimated on thousand to two thousand captives from the Tunica, Taensa, and Quapaw tribes during this period.

Savannah Town, South Carolina had been first observed in the 1670s as a Westo village, located on the Savannah River below the fall line in present day Aiken County.

The Savannah (Shawnee) had displaced the Westos in a 1679-1680 trade war, and the town bore their name on a 1685 Joel Gascoyne Plat of the Province of Carolina.

Savannah Town has become important to the growing colony for its profitable trade with the natives, and for frontier defense.

A thriving business has developed around traders who with their pack horses spread throughout the western wilderness.

The Proprietors in 1692, had hoped for traders to reside at "Savannah town".

Colonel Thomas Welch reaches the Mississippi River in 1698, on a trail that will come to be the Upper Trading Path to the Chickasaw homeland.

Iron and woolen goods are offered in exchange for skins, which will come to be shipped by the thousands from Savannah Town via oared 'periagoe' to Charles Town, and thence Europe.