Jacob Roggeveen

Dutch explorer

Years: 1659 - 1729

Jacob Roggeveen (1 February 1659, Middelburg - 31 January 1729, Middelburg) is a Dutch explorer who is sent to find Terra Australis, but he instead comse across Easter Island.

Jacob Roggeveen also encounters Bora Bora and Maupiti of the Society Islands, Samoa, along with his brother Jan Roggeveen.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 11 total

East Polynesia (1684–1827 CE): First European Sails and Island Transformations

Geographic & Environmental Context

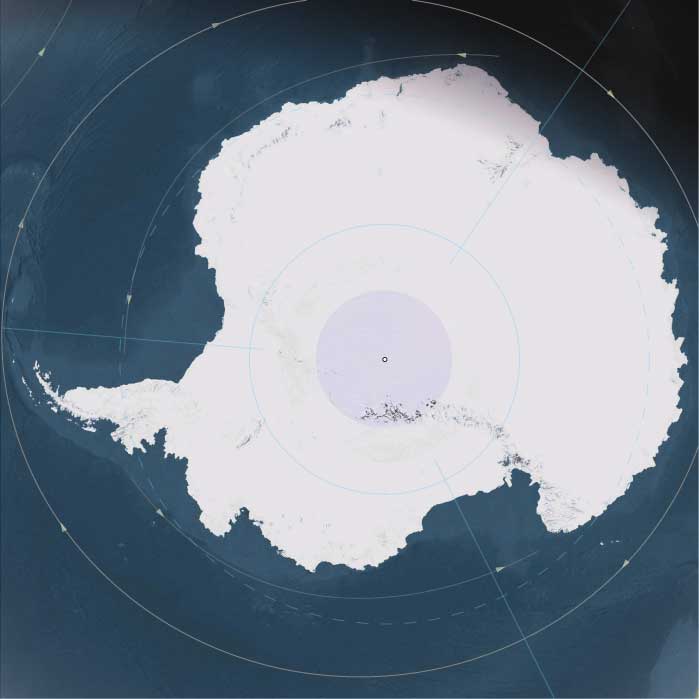

The subregion of East Polynesia includes Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and the Pitcairn Islands (Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie, Oeno). Anchors included the Rano Raraku quarry and ahu-lined coasts of Rapa Nui, the volcanic soils of Pitcairn, the limestone plateau of Henderson, and the low coral cays of Ducie and Oeno. This isolated cluster remained ecologically fragile and culturally distinct, set at the margins of the Pacific until the arrival of European voyagers.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The late Little Ice Age persisted into the 18th century, with drought cycles stressing Rapa Nui’s gardens and Henderson’s limited water sources. Storm surges occasionally swamped Ducie and Oeno. Cooler sea conditions affected fishing yields, while deforestation on Rapa Nui reduced resilience against soil erosion and drought.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Rapa Nui: Rock-mulched gardens produced sweet potato, yams, and gourds; chickens were intensively kept in stone enclosures. Fishing and shellfish provided protein. Social divisions sharpened as resource stress deepened.

-

Pitcairn: Supported small-scale horticulture of root crops and fruit trees, with marine resources supplementing diets. By the 18th century, voyaging connections with Henderson, Ducie, and Oeno appear to have waned.

-

Henderson, Ducie, Oeno: Likely visited only intermittently for seabirds, turtles, and shells; permanent habitation had diminished.

Technology & Material Culture

On Rapa Nui, the tradition of raising moai on ahu waned, giving way to the tangata manu (birdman) cult at Orongo. Petroglyphs of birds and ceremonial houses became central. Stone tools, fishhooks, and weaving continued in daily life. On Pitcairn, adzes and fishhooks remained common, though archaeological evidence suggests dwindling communities.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Canoe routes on Rapa Nui remained coastal and ritual in scope.

-

The Pitcairn group sustained limited inter-island visits, but geographic isolation deepened.

-

European voyages reached the region: Rapa Nui was sighted by Jacob Roggeveen in 1722, later visited by Felipe González de Ahedo (1770), James Cook (1774), and others. The Pitcairns were charted by Philip Carteret (1767) and later became infamous as the refuge of the Bounty mutineers (1790).

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

On Rapa Nui, the tangata manu ritual gained prominence, with annual contests to retrieve the first seabird egg from islets off Orongo symbolizing sacred authority. Oral traditions encoded memories of voyaging ancestors, ecological decline, and clan rivalries. The Pitcairn group retained Polynesian ritual landscapes, but communities were shrinking. The arrival of Europeans introduced crosses, flags, and written records, foreshadowing cultural upheaval.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Rapa Nui’s people intensified chicken keeping, diversified fishing, and maintained lithic mulching to buffer food shortages. Social structures reorganized around ritual authority and warfare. On Pitcairn, small populations combined cultivation with birding and reef foraging. The islets of Henderson, Ducie, and Oeno remained ecological refuges, sustaining wildlife and occasional human visits.

Transition

By 1827 CE, East Polynesia stood at a turning point. Rapa Nui had shifted from the moai era to the tangata manuorder, enduring deep ecological stress yet sustaining cultural resilience. Pitcairn was settled by the descendants of the Bounty mutineers and Polynesian companions, creating a hybrid community of global renown. Henderson, Ducie, and Oeno remained uninhabited but tied into new European cartographies. Once isolated, the eastern edge of Polynesia had entered the orbit of global empires and maritime networks.

Jacob Roggeveen had departed on August 1, 1721, on his expedition, in the service of the Dutch West India Company, to seek Terra Australis.

The expeditionary fleet consists of three ships, the Arend, the Thienhoven, and Afrikaansche Galey.

Roggeveen first sails down to the Falkland Islands (which he renames "Belgia Australis").

Jacob’s father, Arend Roggeveen, was a mathematician with much knowledge of astronomy, geography, rhetorics, philosophy and the theory of navigation as well.

He had occupied himself with study of the mythical Terra Australis, and had even gotten a patent for an exploratory excursion; but it was to be his son who, at the age of 62, eventually equips three ships and makes the expedition.

Before he set out, Jacob Roggeveen had already lived a busy life, having become notary of Middelburg (the capital of the province of Zeeland, where he was born) on March 30, 1683.

He had graduated on August 12, 1690, as a doctor of the law at University of Harderwijk.

He had married Marija Margaerita Vincentius, but she died in October 1694.

He had joined the Dutch East Indies Company in 1706, serving between 1707 and 1714 as a Raadsheer van Justitie ("Council Lord of Justice") at Batavia, Dutch East Indies (now Jakarta).

He had married Anna Adriana Clement there, but she died soon afterward.

He had in 1714 returned alone to Middelburg.

He had become involved in religious controversies, supporting the liberal preacher Pontiaan van Hattem by publishing his leaflet De val van 's werelds afgod ("The fall of the world's idol").

The first part had appeared in 1718, in Middelburg, and was subsequently confiscated by the city council and burned; Roggeveen had fled from Middelburg to nearby Flushing.

He had thereafter, established himself in the small town of Arnemuiden, and published parts two and three of the series, again raising a controversy.

Roggeveen passes through the Strait of Le Maire and ...

...continues to beyond sixty degrees south latitude to enter the Pacific Ocean.

He makes landfall near Valdivia, Chile.

Roggeveen visits the Juan Fernández Islands, where he spends February 24 to March 17.

The Roggeveen expedition, voyaging westward from the Juan Fernandez Islands, finds Easter Island (Rapa Nui) on Easter Sunday, April 5, 1722, whereupon he reports seeing two thousand to three thousand inhabitants.

The number may have been greater, since some may have been frightened into hiding by a misunderstanding that had led Roggeveen's men to fire on the natives, killing more than a dozen and wounding several more.

The first European to visit Rapa Nui, Roggeveen calls it Paaseiland (Easter Island) in commemoration of the sighting day.

Roggeveen finds all the island’s massive stone statues toppled from their bases, an event that had probably occurred during a period of internal conflict possibly brought on by deforestation and the resultant collapse of the social order.

Jacob Roggeveen, following his discovery and naming of Easter Island, sails to Batavia by way of the Tuamotu Archipelago, ...

...the Society Islands, and ...

...Samoa.

Jacob Roggeveen is arrested in Batavia because he had violated the monopoly of the Dutch East India Company, but the Company is later forced to release him, to compensate him for the trouble, and to pay his crew.

Roggeveen will return to the Netherlands in 1723, and publish part four of De val van 's werelds afgod (The fall of the world's idol).