Huan of Han

emperor of the Han Dynasty

Years: 132 - 168

Emperor Huan of Han (132–168) is an emperor of the Chinese Han Dynasty.

He is a great-grandson of Emperor Zhang.

After Emperor Zhi is poisoned to death by the powerful official Liang Ji in 146, Liang Ji persuades his sister, the regent Empress Dowager Liang,to make the 14-year-old Liu Zhi, the Marquess of Liwu, who is betrothed to their sister Liang Nüying, emperor.

As the years pass, Emperor Huan, offended by Liang Ji's autocratic and violent nature, becomes determined to eliminate the Liang family with the help of eunuchs.

Emperor Huan succeeds in removing Liang Ji in 159 but this only serves to increase the influence of the eunuchs over all aspects of government.

Corruption during this period reaches a boiling point and in 166 university students rise up in protest against the government and call on Emperor Huan to eliminate all corrupt officials.

Instead of listening, Emperor Huan orders the arrest of all students involved.

Emperor Huan has largely been viewed as an emperor who might have been intelligent but lacked wisdom in governing his empire, and his reign contributes greatly to the downfall of the Eastern Han Dynasty.

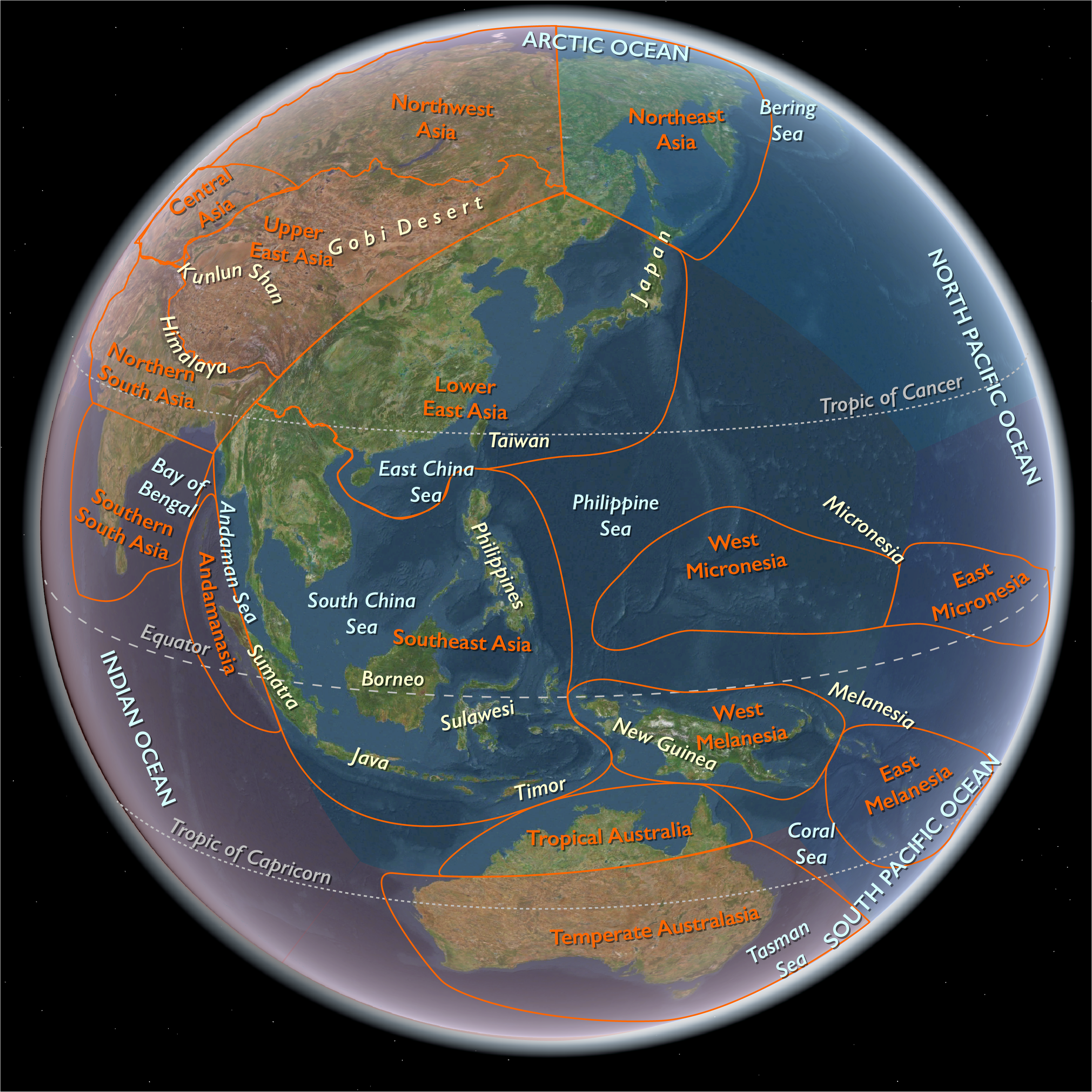

Hou Hanshu (History of the Later Han) recounts that one Roman envoy (perhaps sent by emperor Marcus Aurelius) reached the Chinese capital Luoyang in 166 and was greeted by Emperor Huan.

Emperor Huan dies at 36 in 168 after reigning for 22 years.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 12 total

Emperor Zhi, as young as he is, is keenly aware of how much Liang Ji is abusing power (but befitting of a young child, not aware of how Liang Ji also has the power to do him harm), and on one occasion, at an imperial gathering, he blinks at Liang Ji and refers to him as "an arrogant general."

Liang Ji becomes angry and concerned.

In the summer of 146, he poisons a bowl of pastry soup and has it given to the emperor.

After the young emperor consumes the soup, he quickly experiences great pain; he summons Li immediately and also requests water, believing that water will save him.

However, Liang immediately orders that the emperor not be given any water, and (regardless of whether water would have helped), the young emperor quickly expires.

Li advocates a full investigation, but Liang is able to have the investigation efforts quashed.

After Emperor Zhi's death, Liang Ji, under pressure by the key officials, is forced to summon a meeting of the officials to decide whom to enthrone as the new emperor.

The officials are again largely in favor of Prince Suan, but Liang Ji remains concerned about how the difficulty of controlling an adult emperor, and instead persuades Empress Dowager Liang to make the fourteen-year-old Liu Zhi, the Marquess of Liwu, a great-grandson of Emperor Zhang, to whom Liang Ji's younger sister Liang Nüying is betrothed, emperor (as Emperor Huan).

Empress Dowager Liang continues to serve as regent after Emperor Huan's ascension at age fourteen.

However, her brother Liang Ji is increasingly in complete control, even over the empress dowager.

Emperor Huan posthumously honors his grandfather and father as emperors, but because the empress dowager is regent, does not honor his mother Yan Ming as an empress dowager; rather, she is given the title of an imperial consort. (His father's wife Lady Ma will be belatedly honored as an imperial consort as well in 148.)

In 147, he marries Liang Nüying, the sister of Empress Dowager Liang and Liang Ji, and creates her empress.

It appears that while the Liangs are in control, Emperor Huan is not a complete puppet—but instead, in a portent of things to come, trusts court eunuchs in his decision-making.

In 147 as well, Liang Ji, in conjunction with the eunuchs Tang Heng and Zuo Guan, but with Emperor Huan's clear approval, falsely accuses the honest officials Li Gu and Du Qiao of conspiring to overthrow Emperor Huan and replace him with Prince Suan.

Li and Du are executed, while Prince Suan is demoted to marquess status and commits suicide.

An Shigao, a prince of Parthia, has renounced his claim to the royal throne of Parthia in order to serve as a Buddhist missionary monk.

Nicknamed the "Parthian Marquis", he arrives in China in 148 CE at the Han Dynasty capital of Luoyang, where he produces a substantial number of translations of Indian Buddhist texts and attracts a devoted community of followers.

More than a dozen works by An Shigao are currently extant, including texts dealing with meditation, abhidharma, and basic Buddhist doctrines.

An Shigao's corpus does not contain any Mahāyāna scriptures, though he himself is regularly referred to as a "bodhisattva" in early Chinese sources.

Scholarly studies of his translations have shown that they are most closely affiliated with the Sarvāstivāda school.

An Shigao is the first Buddhist translator to be named in Chinese sources.

Empress Dowager Liang announces in 150 that she is retiring and returning imperial authority to Emperor Huan.

Later this year, she dies.

Emperor Huan then honors his mother as an empress dowager.

However, Liang Ji remains powerful—and perhaps even more powerful than before, without his sister curbing his power.

He becomes increasingly violent and corrupt, stamping out all dissent with threats of death.

He even expels his humble and peace-loving brother Liang Buyi from the government.

Empress Dowager Yan dies in 152.

Because Emperor Huan has inherited the throne through a collateral line, he is not permitted by customs to be the mourner, but instead his brother Liu Shi, the Prince of Pingyuan, serves as chief mourner.

The first major public confrontation between an official and a powerful eunuch, foreshadowing many to come, occurs in 153.

Zhu Mu, the governor of Ji Province (modern center and northern Hebei) had discovered that the father of the powerful eunuch Zhao Zhong had been improperly buried in a jade vest—an honor that was reserved to imperial princes, and he ordered an investigation.

Zhao's father is exhumed, and the jade vest is stripped away—an act that angers Zhao and Emperor Huan.

Zhu is not only removed from his post but is sentenced to hard labor.

Emperor Huan becomes increasingly disgruntled at Liang Ji's control of the government as the years pass, and is also angered by Empress Liang's behavior.

Because of her position as Empress Dowager Liang and Liang Ji's sister, Empress Liang is wasteful in her luxurious living, far exceeding any past empress, and is exceedingly jealous.

She does not have a son, and because she does not want any other imperial consorts to have sons, if one becomes pregnant, Empress Liang finds some way to murder her.

Emperor Huan does not dare to react to her due to Liang Ji's power, but rarely has sexual relations with her.

Angry and depressed that she has lost her husband's favor, Empress Liang dies in 159, initiating a chain of events that lead to Liang Ji's downfall.

Liang, in order to continue to control Emperor Huan, has adopted his wife's beautiful cousin Deng Mengnü (the stepdaughter of her uncle Liang Ji (written with a different Chinese character despite the same pronunciation), as his own daughter, changing her family name to Liang.

He and Sun give Liang Mengnü to Emperor Huan as an imperial consort, and, after Empress Liang's death, they hope that she will be eventually created empress.

To completely control her, Liang Ji plans to have her mother, Lady Xuan , killed, and in fact sends assassins against her, but the assassination is foiled by the powerful eunuch Yuan She, a neighbor of Lady Xuan.

Lady Xuan reports the assassination attempt to Emperor Huan, who is greatly angered.

He enters into a conspiracy with eunuchs Tang Heng, Zuo Guan, Dan Chao, Xu Huang, and Ju Yuan to overthrow Liang—sealing the oath by biting open Dan's arm and swearing by his blood.

Liang Ji has some suspicions about what Emperor Huan and the eunuchs are up to, and investigates.

The five eunuchs quickly react.

They have Emperor Huan openly announce that he is taking back power from Liang Ji and mobilize the imperial guards to defend the palace against a counterattack by Liang.

They then surround Liang's house and force him to surrender.

Liang and Sun, unable to respond with any force, commit suicide.

The entire Liang and Sun clans (except for Liang Ji's brothers Li Buyi and Liang Meng, who had previously already died) are arrested and slaughtered.

A large number of officials are executed or deposed for close association with Liang—so many that the government is almost unable to function for some time.

Liang and Sun's properties are confiscated by the imperial treasury, which allows the government to reduce taxes.

After Liang Ji's death, Emperor Huan creates Liang Mengnü empress, but dislikes her family name, and therefore orders her to take the family name Bo.

Later, he discovers that her original family name was actually Deng, and therefore has her family name restored.

The people have great expectations for Emperor Huan's administration after the death of Liang Ji.

However, having been able to overthrow Liang Ji with the five eunuchs' help, Emperor Huan greatly rewards them, creating them and several other eunuchs who had participated in the coup d'état marquesses and further gives them governmental posts that confer tremendous power.

Further, the five eunuch-marquesses openly engage in massive corruption and become extremely wealthy, with Emperor Huan's approval.

Emperor Huan himself is also corrupt and unwilling to accept any criticism.

In 159, when the honest county magistrate Li Yun submits a petition urging him to curb the power of the eunuchs, Emperor Huan is deeply offended that he has included the phrase, "Is the emperor turning blind?"

and, despite intercessions by a number of officials and even some fair-minded eunuchs, has Li and his friend Du Zhong both executed.

Emperor Huan, apparently in reaction to spending due to renewed Qiang rebellions and new agrarian revolts, issues an edict in 161, offering minor offices for sale—including imperial guard officer positions.

(A bad precedent, thus established, this practice will become even more prevalent and problematic under Huan's successor, Emperor Ling.)

While Huan actually appears to have a knack for finding good generals to suppress the rebellions or to persuade the rebels to surrender, the rampant corruption will cause new rebellions as soon as the old ones are quelled.

Emperor Huan, perhaps finally fed up with the eunuchs' excess, in 165, demotes Ju, the only one remaining of the original five who had helped him overthrow Liang Ji six years earlier.

Several other corrupt eunuchs are also demoted or deposed, but their powers are soon restored.

For the rest of Huan's reign, there will be a cyclical rising and falling of the eunuchs’ power after conflicts with officials, but each time the eunuchs prevail, becoming more powerful than before.

Emperor Huan, apparently tired of Empress Deng and of her disputes with his favorite, Consort Guo, deposes and imprisons her later in this year.

She dies in anger, and several of her family members are executed.

He wants to bestow the empress title upon another consort, Tian Sheng, but officials oppose this measure because she is of lowly birth, and recommend that he instead elevate Consort Dou Miao, the daughter of Dou Wu, a Confucian scholar and a descendant of Dou Rong, who had contributed much to the establishment of the Eastern Han Dynasty.

Emperor Huan does not favor Consort Dou, but yields to pressure and names her empress.

A major public confrontation between Imperial Academy students and eunuchs in 166 evolves into a major incident.

The governor of the capital province (modern western Henan and central Shaanxi), Li Ying, had arrested and executed a fortuneteller named Zhang Cheng, who had had his son kill a man, having predicted that a general pardon was coming.

Li is arrested, and some two hundred Academy students sign a petition requesting his release—which further angers Emperor Huan, who has the students arrested.

Only after about a year, and Dou Wu's intercession, are Li and the students released, but all of them have their citizenship rights stripped.

This incident is later known as the first Disaster of Partisan Prohibition.

As recorded in the Hou Hanshu, a possible contact between Rome and Han China occurs in 166 when a Roman traveler visits the court of Emperor Huan, claiming to be an ambassador representing a certain Andun, who can be identified either with Marcus Aurelius or his predecessor Antoninus Pius.

Rafe de Crespigny asserts that this was most likely a group of Roman merchants.

(de Crespigny, Rafe.

[2007].

A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD).

Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.)

Other travelers to Eastern-Han China include Buddhist monks who translate works into Chinese, such as An Shigao of Parthia, and Lokaksema from Kushan-era Gandhara, India.