Hongwu Emperor

Emperor of the Ming Dynasty

Years: 1328 - 1398

The Hongwu Emperor (21 October 1328 – 24 June 1398), also known by his given name Zhu Yuanzhang and his temple name Ming Taizu (lit.

"Great Ancestor of the Ming"), is the founder and first emperor of the Ming Dynasty of China.

His era name Hongwu means "vastly martial".

In the middle of the 14th century, with famine, plagues, and peasant revolts sweeping across China, Zhu risew to command over the army that conquerw China and endw the Yuan Dynasty, forcing the Mongols to retreat to the central Asian steppe.

Following his seizure of the Yuan capital Khanbaliq (modern Beijing), Zhu claims the Mandate of Heaven and establishes the Ming Dynasty in 1368.

Trusting only in his family, he creates his many sons as powerful feudal princes along the northern marches and the Yangtze valley.

Having outlived his first successor, the Hongwu Emperor enthrones his grandson via a series of instructions; this ends in failure when the Jianwen Emperor's attempt to unseat his uncles leads to the Yongle Emperor's successful rebellion.

Most of the historical sites related to Zhu Yuanzhang are located in Nanjing, the original capital of his dynasty.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 18 total

East Asia (1252–1395 CE): State Transitions, Frontier Realignments, and Maritime–Continental Networks

From the coasts of Fujian and Kyūshū to the high passes of Tibet and the grasslands of Mongolia, East Asia in the Lower Late Medieval Age was a landscape of transition and renewal. Empires fractured and recomposed; faiths and artistic schools crossed linguistic and political frontiers; and the rhythms of monsoon trade and steppe migration bound mountains, river basins, and seas into a single, evolving system.

The late thirteenth century brought the consolidation of Mongol rule. The Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) unified northern and southern China, established provincial administrations, and incorporated Yunnan and Guizhou through tusichieftaincies that tied mountain societies to imperial administration. Mongol garrisons in Liaodong and the Amur basin secured tribute from Jurchen and Tungusic groups, while the maritime ports of Fujian—particularly Quanzhou (Zaitun)—flourished as global entrepôts, handling aromatics, spices, and porcelains bound for India, Arabia, and the Red Sea. In the fertile south, double-cropped rice, tea, silk, and cotton sustained population growth, and the Sichuan Basin thrived on its rice–mulberry economy and salt industries. Yet by the mid-fourteenth century, a conjunction of floods, famine, inflation, and rebellion eroded Mongol control. The Yellow River repeatedly changed course, epidemics spread, and the Red Turban uprisings swept the Lower Yangtze. From these convulsions arose Zhu Yuanzhang, who in 1368 founded the Ming dynasty, restoring Chinese governance on Confucian foundations and re-establishing hydraulic, fiscal, and agrarian order by century’s end.

Across the Korean Peninsula, the Goryeo kingdom endured decades of Mongol invasion and suzerainty, its royal house intermarried with Yuan princesses and its provinces dotted with garrisons. Despite political strain, Seon (Zen) monasteries prospered, celadon ceramics achieved luminous refinement, and the Tripitaka Koreana—a carved woodblock canon—stood as both spiritual and cultural monument. By the late fourteenth century, reformist scholars such as Jeong Do-jeon joined General Yi Seong-gye in overthrowing the dynasty. The founding of Joseon in 1392 signaled a decisive turn toward Neo-Confucian governance, rationalized land tenure, and meritocratic examinations—institutions that would define Korea for centuries.

Across the sea, Japan followed its own arc of upheaval. The Kamakura bakufu, having repelled the Mongol invasions of 1274 and 1281, emerged victorious but fiscally weakened. Imperial restoration under Emperor Go-Daigo (1333–1336) collapsed within three years, giving way to the Ashikaga (Muromachi) shogunate. The subsequent Nanboku-chō dual-court era fragmented authority, yet provincial shugo and rising daimyō consolidated local power, forming the foundations of later feudal domains. Despite turbulence, Zen monasteries flourished; Nō theater, ink painting, and garden design flowered under warrior patronage; and maritime trade, mingled with wakō piracy, tied Kyūshū and the Inland Sea to the coasts of Korea and China.

Beyond the agrarian cores, frontier worlds underwent their own transformations. In Mongolia, the fall of the Yuan drove the imperial court northward, forming the Northern Yuan under descendants of Kublai. Karakorum remained a sacred center, yet steppe authority splintered among rival lineages and the rising Oirat confederations. In Xinjiang, the Chagatai Khanate fractured; out of its eastern reaches arose Moghulistan, founded by Tughluq Temür in 1347, which embraced Islam and forged an enduring Turko-Mongol synthesis. Oasis cities such as Kashgar, Yarkand, and Turfan prospered on caravan trade, exporting jade, cotton, and felt while importing silk, tea, and metal goods from China.

Farther south, the high plateaus of Tibet passed from the Mongol-backed Sakya hierarchy to a revival of indigenous rule under the Phagmo Drupa in the 1350s. The lama–patron system established by the Yuan endured in modified form as monasteries managed estates, bridges, and granaries linking religious and economic authority. In Amdo and Kham, the Tea–Horse routes between Chengdu, Kangding, and Lhasa moved Chinese tea and cloth in exchange for ponies, wool, and salt, while reformist teaching by Tsongkhapa (b. 1357) began to shape the intellectual currents that would crystallize the Geluk school. Along the Hexi Corridor, the Yuan postal system connected Dadu (Beijing) to Dunhuang, with way-stations guarding the Silk Road’s last continental trunk; the early Ming rebuilt these fortresses, establishing beacon towers and grain garrisons that anchored the empire’s western frontier.

Across this immense region, technological and cultural innovations paralleled political change. The Yuan expanded the use of gunpowder in siege craft and field warfare; the Ming standardized artillery and rebuilt river defenses. In Korea, metal movable type produced the Jikji (1377), while in China blue-and-white porcelain and Longquan celadon reached new heights. Japan’s Zen gardens and Nō theater transformed aesthetic restraint into spiritual expression. Neo-Confucian scholarship revived across China and Korea; Chan/Zen meditation reshaped samurai ethics; and Tibetan monasteries integrated scholasticism with ritual authority. Commerce and culture thrived together: the Grand Canalmoved grain and manufactures north–south, Sichuan’s salt and tea funded state revenues, and the maritime Silk Road carried goods from the Lower Yangtze to Kyūshū and Goryeo ports. Even the Austronesian communities of Taiwanremained intermittently connected, trading deer hides and hemp cloth to visiting Fujian sailors who mapped these littoral margins.

The fourteenth century’s climatic cooling and political violence tested every institution, yet East Asia adapted through hydraulic renewal, market resilience, and intellectual synthesis. The Ming re-centralized China on stable agrarian and fiscal foundations; Joseon codified Confucian bureaucracy and scholarship; and Muromachi Japan balanced warrior rule with a flowering of Zen culture. On the steppe and in the highlands, Northern Yuan, Moghulistan, and Phagmo Drupa Tibet reconstituted power through mobility, trade, and faith.

By 1395 CE, the region stood reorganized yet interconnected—a constellation of agrarian monarchies and frontier polities linked by caravans, sea lanes, and shared technologies. The systems rebuilt in these decades—irrigation, bureaucracy, Buddhist and Confucian learning, and maritime enterprise—formed the durable scaffolding upon which the early modern East Asian world would rise.

Maritime East Asia (1252–1395 CE): Mongol Oceans, Coastal Polities, and Early Ming Retrenchment

Geographic & Environmental Context

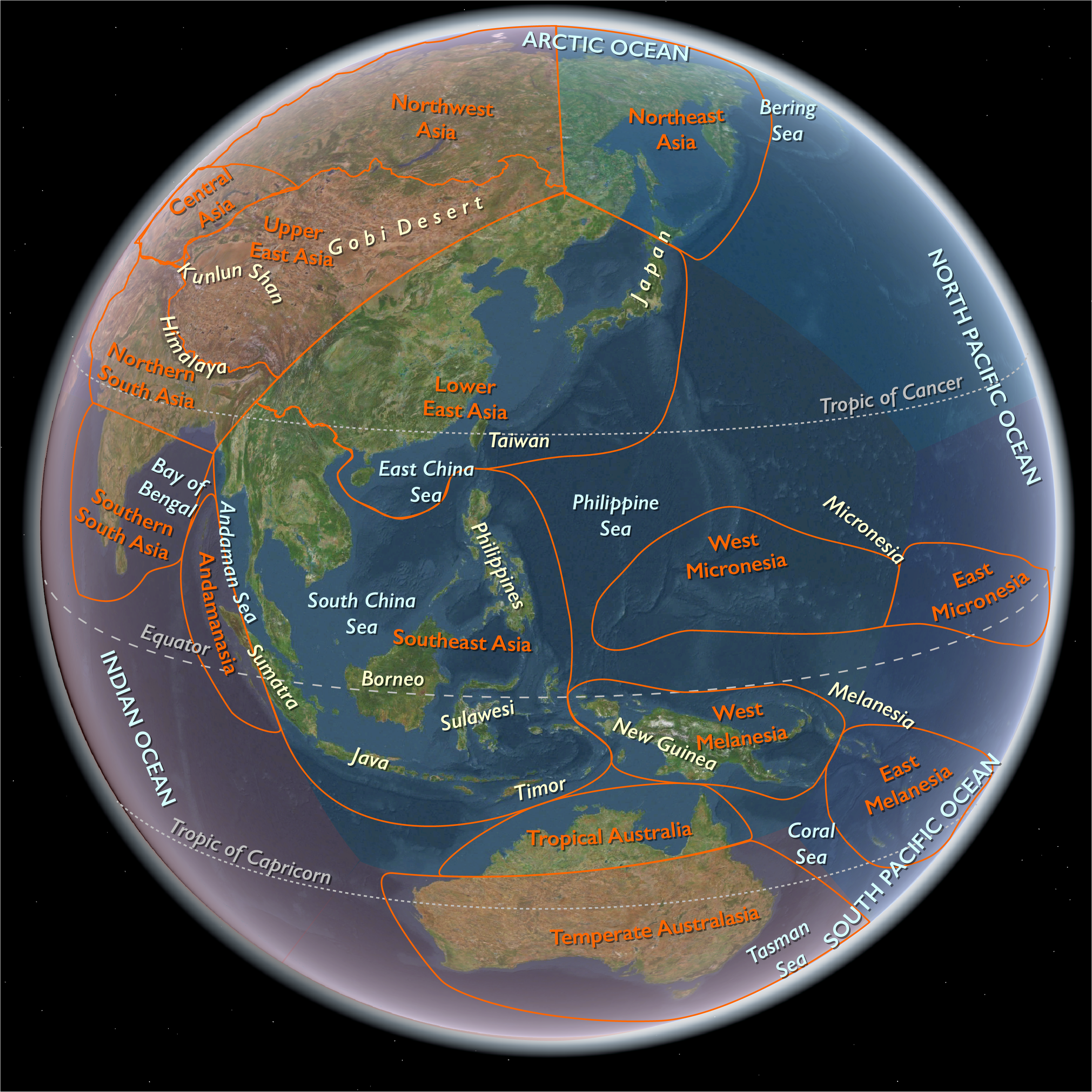

Maritime East Asia in this era ran from the South China Sea and East China Sea shelves up through the Korean Peninsula and Primorsky coast to Kyushu–Honshu–Shikoku–southwestern Hokkaidō, including Taiwan and the Ryukyu–Izu chains. The Little Ice Age’s cooler phases sharpened winter monsoon winds, while typhoons remained seasonally destructive—nowhere more consequential than in 1274 and 1281, when storms helped destroy the Mongol invasion fleets against Japan. Lower-frequency drought–flood swings shaped harvests along the Yangtze–Yellow basins and on the peninsula, and episodic earthquakes and storm surges reworked deltaic and bayhead settlements.

Political & Social Developments

-

Southern Song → Yuan (1271–1368): The Mongol conquest culminated at sea: Song naval resistance was finally crushed off the Pearl River delta (1279). Under the Yuan, coastal prefectures were militarized and reorganized; Quanzhou (Zayton) stood as a cosmopolitan entrepôt with Muslim merchant communities, while northern arsenals and river fleets supported Mongol campaigns.

-

Goryeo under Mongol suzerainty: After invasions (1230s–1270), Goryeo integrated into the Yuan imperial sphere, supplying ships and men for the failed Japan expeditions. Court–provincial balances shifted; coastal defense and tribute logistics intensified.

-

Japan: Kamakura → Kenmu → Muromachi (Ashikaga): The Kamakura bakufu repelled the Mongols but never recovered its fiscal footing; political rupture produced the Kenmu Restoration (1333), then the Ashikaga shogunate (1336) and the Northern–Southern Courts period (Nanbokuchō). Maritime lords and inland sea coalitions grew; piracy and coastal privateering (early wakō) swelled in the vacuum.

-

Ryukyu & Taiwan: The Ryukyu archipelago remained divided among polities (Chūzan, Hokuzan, Nanzan), mediating regional trade; Taiwan was home to Austronesian societies interacting with Fujian fishers and traders on a seasonal, extra-official basis.

-

Ming founding (1368): Hongwu’s early Ming state reconsolidated river–coast governance, imposed maritime bans (haijin) on private overseas trade, and reshaped the tribute order—partly to curtail piracy and curb coastal warlord power.

Economy & Trade

Yuan China kept the maritime silk road humming via Quanzhou, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Guangzhou, linking to Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. Paper money and tax-in-kind systems coexisted uneasily; the Black Death (1340s) destabilized networks, undermining labor and revenue. In Korea, grain–textile tribute and coastal salt/fish trades endured despite exactions. In Japan, with Song coin imports dwindling, regional markets leaned on rice taxes, barter, and local mint substitutes; Seto Inland Sea routes flourished under maritime leagues. The haijin after 1368 throttled private Chinese shipping but could not fully suppress extra-legal exchange—especially across the Fujian–Ryukyu–Kyushu triangle.

Technology & Material Culture

Compass navigation, sternpost rudders, multi-masted junks, and riverine–coastal arsenals characterized Yuan maritime power. Gunpowder weapons proliferated in siege and shipboard use. Ceramics—Longquan celadons, Cizhou wares, and early underglaze blue—moved in volume. In Korea, Goryeo celadon reached its late maturity; in Japan, Zen aesthetics shaped temple carpentry and garden craft; swordsmithing remained a prestige technology.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Tsushima/Korea/Japan straits: tribute, hostage exchanges, and anti-piracy negotiations.

-

Fujian–Ryukyu–Kyushu coastal arc: semi-licit circuits for copper, salt, ceramics, timber, sulfur, and fish.

-

Grand Canal–Yangtze–East China Sea: grain tribute to northern capitals; Ningbo and Quanzhou as seaward gates.

Flows of people included Central Asian merchants, maritime soldiers, and religious communities (Muslim, Nestorian remnants) under the Yuan; after 1368, controlled tribute missions replaced open commerce.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Chan/Zen Buddhism linked Song–Yuan China to Japan’s Kamakura–Muromachi culture (temples, ink painting, tea). Neo-Confucian learning deepened in Goryeo academies; literati poetry and theater circulated with envoys. The “divine wind” (kamikaze) mythos crystallized in Japan’s memory; coastal epigraphy at Quanzhou recorded a pluralistic maritime society.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Coastal communities shifted port sites after siltation, rebuilt after storms, and diversified from rice to salt, mulberry, and fisheries. Goryeo reclaimed tidal flats; Japanese inland sea polities fortified narrows and stockpiled grain. Early Ming haijin protected some coastlines from slaving raids but displaced livelihoods; smuggling and wakō adapted in turn.

Transition to the Next Age

By 1395, Ming consolidation and Joseon’s imminent founding (1392) recast peninsular and continental orders; Ryukyu was poised for unification and tributary brokerage; Japan’s Ashikaga polity stabilized but remained factional. The stage was set for state-managed seas—and for the paradox of Ming maritime ambition and prohibition to come

The last of the nine successors of Kublai is expelled from Dadu in 1368 by Zhu Yuanzhang, the founder of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), and dies in Karakorum in 1370.

Although Zhu, who adopts Mongol military methods, drives the Mongols out of China, he does not destroy their power.

A later Chinese army invades Mongolia in 1380.

In 1388 a decisive victory is won; about seventy thousand Mongols are taken prisoner, and Karakorum is annihilated.

The Chinese novel entitled Water Margin (Shui Hu Zhuan, sometimes abbreviated to Shui Hu), attributed to Shi Nai'an, is also translated as Outlaws of the Marsh, Tale of the Marshes, All Men Are Brothers, Men of the Marshes, or The Marshes of Mount Liang.

Considered one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature, the novel is written in vernacular Chinese rather than Classical Chinese.

The story, set in the Song dynasty, tells of how a group of outlaws gathers at Mount Liang (or Liangshan Marsh) to form a sizable army before they are eventually granted amnesty by the government and sent on campaigns to resist foreign invaders and suppress rebel forces.

It will introduce to readers many of the most well known characters in Chinese literature, such as Wu Song, Lin Chong and Lu Zhishen.

Stories about the outlaws became a popular subject for Yuan dynasty drama.

During this time, the material on which Water Margin is based evolves into what it is in the present.

The number of outlaws increases to 108.

Even though they came from different backgrounds (including scholars, fishermen, imperial drill instructors etc.), all of them eventually came to occupy Mount Liang (or Liangshan Marsh).

There is a theory that Water Margin became popular during the Yuan era as the common people (predominantly Han Chinese) resented the Mongol rulers.

The outlaws' rebellion was deemed "safe" to promote as it was supposedly a negative reflection of the fallen Song dynasty.

Concurrently, the rebellion was also a call for the common people to rise up against corruption in the government.

The first signs of the White Lotus Society had come during the late thirteenth century.

Mongol rule over China, known also by its dynastic name, the Yuan dynasty,had prompted small, yet popular demonstrations against foreign rule.

The White Lotus Society had taken part in some of these protests as they grew into widespread dissent.

The Mongols considered the White Lotus society a heterodox religious sect and banned it, forcing its members to go underground.

Now a secret society, the White Lotus became an instrument of quasi-national resistance and religious organization.

A revolution, inspired by the White Lotus society, takes shape in 1352 around Guangzhou.

A Buddhist monk and former boy-beggar, Zhu Yuanzhang, throws off his vestments and joins the rebellion.

His exceptional intelligence takes him to the head of a rebel army; he wins people to his side by forbidding his soldiers to pillage, in observance of White Lotus religious beliefs.

The Red Turban Rebellion has spread through much of China by 1355.

Zhu Yuanzhang captures Nanjing in 1356 and makes it his capital.

It is here that he begins to discard his heterodox beliefs and so wins the help of Confucian scholars who issue pronouncements for him and perform rituals in his claim of the Mandate of Heaven, the first step toward establishing new dynastic rule.

Meanwhile the Mongols are fighting among themselves, inhibiting their ability to suppress the rebellion.

Lithai, who served as uparat during the reign of his father, Lerthai, from the city of Srisatchanalai, an important urban center of the early Sukhothai kingdom, had succeeded to the Sukhothai throne in 1347.

Lithai is known as the writer of the Traiphuum Phra Ruang ('Three worlds of Phra Ruang', Phra Ruang being the dynastic name of Lithai's linneage), a religious text describing the various world of Buddhist cosmology, and the way in which karma consigns living beings to one world or another.

The Traiphuum will go on to serve as an important political document, being reinterpreted in response to changes in the domestic and international political scene.

The Mongol Yüan Dynasty of Kublai Khan and his successors lasts until 1368, when massive peasant uprisings, led by a lowborn Buddhist monk turned warlord, Zhu Yuanzhang, topple Mongol rule; the Chinese use gunpowder to expel their overlords.

The successful peasant revolt spawns the indigenous Ming dynasty, whose first emperor, Zhu, takes the reign title of Hongwu (Hung-wu) and rules from Nanjing in the south.

Ming emperor Hongwu takes the Mongol capital of Beijing in 1368 and institutes despotic rule on a scale unprecedented in China.

Many of China’s Mongol inhabitants, never having assimilated into the population during the century of Mongol rule, return first driving the Mongols first to Shang-to and then to Outer Mongolia.

Ukhaantu Khan, born Toghun Temür, the Yuan Dynasty Emperor of China, a khanate of the Mongol Empire, has lost China to the Ming Dynasty, and concentrates his preparation for reconquest of China at Khara-Khoto.

He dies here in 1370 and his son Ayushiridara succeeds to the throne.

The Mongolia-based empire maintains its influence, stretching its domination from the Sea of Japan to Altai Mountains.

There are also pro-Mongol, anti-Ming forces in Yunnan and Guizhou.

Even though its control over China had not been stablized as yet, the Ming considered that the Yuan had lost the Mandate of Heaven when the dynasty abandoned Dadu, and that the Yuan had been overthrown in 1368.

The Chinese do not treat Toghun Temür after 1368 and his successor Ayushiridar as emperors.