Felipe González de Ahedo

Spanish navigator and cartographer

Years: 1702 - 1792

Felipe González de Ahedo, also spelled Phelipe González y Haedo (Santoña, Cantabria, 1702–1792), is a Spanish navigator and cartographer known for annexing Easter Island in 1770.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 3 events out of 3 total

East Polynesia (1684–1827 CE): First European Sails and Island Transformations

Geographic & Environmental Context

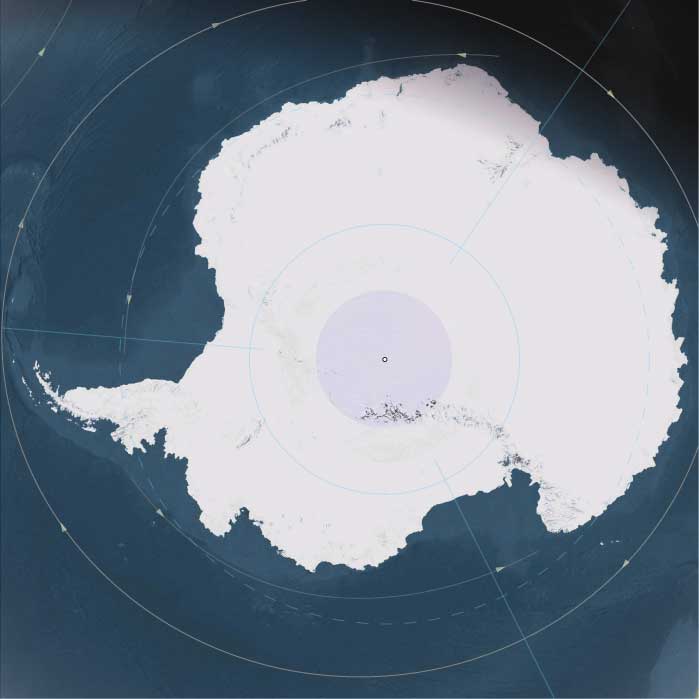

The subregion of East Polynesia includes Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and the Pitcairn Islands (Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie, Oeno). Anchors included the Rano Raraku quarry and ahu-lined coasts of Rapa Nui, the volcanic soils of Pitcairn, the limestone plateau of Henderson, and the low coral cays of Ducie and Oeno. This isolated cluster remained ecologically fragile and culturally distinct, set at the margins of the Pacific until the arrival of European voyagers.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The late Little Ice Age persisted into the 18th century, with drought cycles stressing Rapa Nui’s gardens and Henderson’s limited water sources. Storm surges occasionally swamped Ducie and Oeno. Cooler sea conditions affected fishing yields, while deforestation on Rapa Nui reduced resilience against soil erosion and drought.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Rapa Nui: Rock-mulched gardens produced sweet potato, yams, and gourds; chickens were intensively kept in stone enclosures. Fishing and shellfish provided protein. Social divisions sharpened as resource stress deepened.

-

Pitcairn: Supported small-scale horticulture of root crops and fruit trees, with marine resources supplementing diets. By the 18th century, voyaging connections with Henderson, Ducie, and Oeno appear to have waned.

-

Henderson, Ducie, Oeno: Likely visited only intermittently for seabirds, turtles, and shells; permanent habitation had diminished.

Technology & Material Culture

On Rapa Nui, the tradition of raising moai on ahu waned, giving way to the tangata manu (birdman) cult at Orongo. Petroglyphs of birds and ceremonial houses became central. Stone tools, fishhooks, and weaving continued in daily life. On Pitcairn, adzes and fishhooks remained common, though archaeological evidence suggests dwindling communities.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Canoe routes on Rapa Nui remained coastal and ritual in scope.

-

The Pitcairn group sustained limited inter-island visits, but geographic isolation deepened.

-

European voyages reached the region: Rapa Nui was sighted by Jacob Roggeveen in 1722, later visited by Felipe González de Ahedo (1770), James Cook (1774), and others. The Pitcairns were charted by Philip Carteret (1767) and later became infamous as the refuge of the Bounty mutineers (1790).

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

On Rapa Nui, the tangata manu ritual gained prominence, with annual contests to retrieve the first seabird egg from islets off Orongo symbolizing sacred authority. Oral traditions encoded memories of voyaging ancestors, ecological decline, and clan rivalries. The Pitcairn group retained Polynesian ritual landscapes, but communities were shrinking. The arrival of Europeans introduced crosses, flags, and written records, foreshadowing cultural upheaval.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Rapa Nui’s people intensified chicken keeping, diversified fishing, and maintained lithic mulching to buffer food shortages. Social structures reorganized around ritual authority and warfare. On Pitcairn, small populations combined cultivation with birding and reef foraging. The islets of Henderson, Ducie, and Oeno remained ecological refuges, sustaining wildlife and occasional human visits.

Transition

By 1827 CE, East Polynesia stood at a turning point. Rapa Nui had shifted from the moai era to the tangata manuorder, enduring deep ecological stress yet sustaining cultural resilience. Pitcairn was settled by the descendants of the Bounty mutineers and Polynesian companions, creating a hybrid community of global renown. Henderson, Ducie, and Oeno remained uninhabited but tied into new European cartographies. Once isolated, the eastern edge of Polynesia had entered the orbit of global empires and maritime networks.

The tallness of Easter Islanders, noted originally by Roggeveen in 1722, had been witnessed also by the Spanish who visited the island in 1770, measuring heights of one hunded and ninety-six and one hundred and ninety-nine centimeters.

The two Spanish ships, San Lorenzo and Santa Rosalia, sent by the Viceroy of Peru, Manuel Amat, and commanded by Felipe González de Ahedo, spend five days in the island, performing a very thorough survey of its coast, and name it Isla de San Carlos, taking possession on behalf of King Charles III of Spain, and ceremoniously erect three wooden crosses on top of three small hills on Poike.

They report the island as largely uncultivated, with a seashore lined with stone statues.

East Polynesia (1828–1971 CE): Missionaries, Colonial Rule, and Remote Resilience

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of East Polynesia includes Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and the Pitcairn Islands (Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie, Oeno). Anchors included the Orongo ceremonial village and Rano Kau crater on Rapa Nui, the volcanic soils of Pitcairn, the limestone plateau of Henderson, and the low coral cays of Ducie and Oeno. These islands remained among the most remote and sparsely populated corners of the Pacific, increasingly tied to European and later global powers.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Climate moderated after the Little Ice Age, though droughts still stressed Rapa Nui’s gardens and freshwater shortages persisted on Pitcairn and Henderson. Hurricanes and cyclones occasionally struck Ducie and Oeno, scouring fragile islets. Deforested landscapes on Rapa Nui worsened soil erosion; Pitcairn’s limited farmland supported only modest subsistence.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Rapa Nui: After devastating raids by Peruvian slavers in the 1860s and epidemics, the population collapsed to barely a hundred. Survivors rebuilt communities under Catholic mission leadership. In 1888, Rapa Nui was annexed by Chile, becoming a remote colonial territory. Pastoral ranching, particularly sheep introduced by colonists, reshaped landscapes.

-

Pitcairn: Settled since 1790 by the Bounty mutineers and their Polynesian companions, Pitcairn grew to a few hundred by the mid-19th century. In 1856, overpopulation led to relocation of the community to Norfolk Island, though some later returned. Pitcairn remained a small British dependency, supported by subsistence farming and limited trade.

-

Henderson, Ducie, Oeno: Uninhabited, though occasionally visited by Pitcairn islanders, whalers, and later scientific expeditions.

Technology & Material Culture

Missionaries on Rapa Nui introduced churches, schools, and stone ranch buildings, replacing earlier ceremonial centers. Polynesian oral traditions persisted in song and carving. On Pitcairn, houses of wood and stone, subsistence gardens, and small boats dominated material culture. Religious life was marked by conversion to Seventh-day Adventism in the late 19th century, which strongly shaped Pitcairn identity.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Rapa Nui was drawn into Chilean shipping routes from Valparaíso.

-

Pitcairn relied on infrequent visits from passing ships, later connected irregularly to New Zealand.

-

Whaling and sealing ships traversed the South Pacific, occasionally using these islands for water and provisions.

-

Global missionary networks tied both Rapa Nui and Pitcairn to wider Christian movements.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

On Rapa Nui, ancestral traditions persisted in oral lore, despite suppression of the tangata manu cult by missionaries. Catholic feasts and syncretic practices marked the annual calendar.

-

Pitcairn Islanders, descendants of Bounty mutineers and Polynesians, crafted a distinct English–Polynesian creole culture. Their faith, storytelling, and songs became central to identity, along with genealogical memory of the Bounty.

-

Henderson, Ducie, and Oeno carried symbolic value as ecological sanctuaries, later subjects of scientific exploration.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Rapa Nui’s people adapted deforested soils through stone mulching and subsistence gardening. Sheep ranching under Chilean administration degraded landscapes further, yet communities preserved resilience through kinship, ritual, and persistence. Pitcairn Islanders relied on mixed subsistence—bananas, sweet potatoes, chickens, and fishing—balanced by cooperation and self-sufficiency. Isolation remained both challenge and protection.

Transition

By 1971 CE, East Polynesia had entered modern global networks while remaining highly isolated. Rapa Nui was firmly Chilean territory, marked by cultural revival efforts amid colonial marginalization. Pitcairn survived as a micro-community of fewer than 100 people, still a British dependency. Henderson, Ducie, and Oeno remained uninhabited but ecologically significant. Across the subregion, Indigenous memory, missionary legacies, and colonial frameworks intertwined, sustaining fragile yet enduring human presence at the farthest reaches of Polynesia.