Diogo Lopes de Sequeira

Portuguese fidalgo

Years: 1465 - 1530

Dom Diogo Lopes de Sequeira (1465–1530) is a Portuguese fidalgo.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 7 events out of 7 total

Ferdinand Magellan was born in northern Portugal in around 1480, either at Vila Nova de Gaia, near Porto, in Douro Litoral Province, or at Sabrosa, near Vila Real, in Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro Province.

He is the son of the late Rodrigo de Magalhães, Alcaide-Mor of Aveiro, son of Pedro Afonso de Magalhães and wife Quinta de Sousa) and wife Alda de Mesquita and brother of Leonor or Genebra de Magalhães, wife with issue of João Fernandes Barbosa.

After the death of his parents during his tenth year, he became a page to Queen Leonor at the Portuguese royal court.

In March 1505 at the age of twenty-five, Magellan had enlisted in the fleet of twenty-two ships sent to host Don Francisco de Almeida as the first viceroy of Portuguese India.

Although his name does not appear in the chronicles, it is known that he remained there eight years, in Goa, Cochin and Quilon.

He has participated in several battles, including the battle of Cannanore in 1506, where he was wounded.

In 1509, he fought in the battle of Diu.

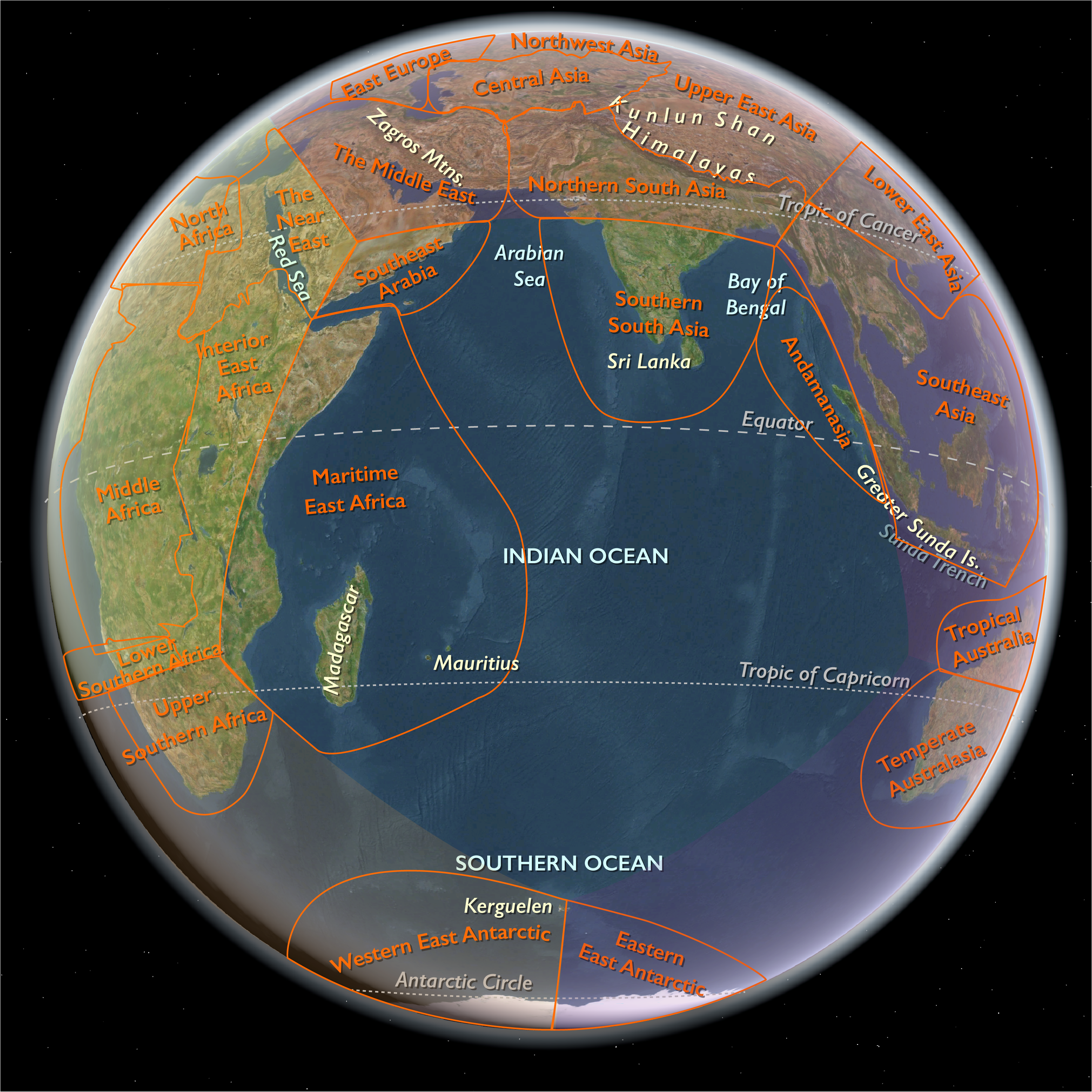

He now sails under Diogo Lopes de Sequeira in the first Portuguese embassy to Malacca, a spice-trading center on the Malay Peninsula, with Francisco Serrão, his friend and cousin.

Sequeira tries to establish contact with the Sultan of Malacca in September 1509 but the expedition falls victim to a conspiracy ending in retreat.

Magellan has a crucial role, warning Sequeira and saving Serrão, who had landed.

They leave behind nineteen Portuguese prisoners.

Albuquerque is described by Fernão Lopes de Castanheda as patiently enduring open opposition from the group that has gathered around Almeida, with whom he keeps formal contact.

Increasingly isolated, he writes to Diogo Lopes de Sequeira, who, sent to analyze the trade potential in Madagascar and Malacca, arrives in India with a new fleet in September 1509, but is ignored as Sequeira joins the Viceroy.

At the same time, Albuquerque refuses approaches from opponents of the Viceroy, who encourage him to seize power.

Francisco de Almeida had sailed for Portugal in December 1509 and reached Table Bay near the Cape of Good Hope, where the Garcia, Belém and Santa Cruz had dropped anchor late February, 1510, to replenish water.

Here the returning Portuguese merchant-warriors encounter the local indigenous people, the Khoikhoi.

The Khoikhoi, originally part of a pastoral culture and language group to be found across Southern Africa, originated in the northern area of modern Botswana.

Southward migration of the ethnic group had been steady, eventually reaching the Cape around the first century CE.

Khoikhoi subgroups include the Namaqua to the west, the Korana of mid-South Africa, and the Khoikhoi in the south.

Husbandry of sheep, goats and cattle, who graze in fertile valleys across the region, have provided a stable, balanced diet, and have allowed the Khoikhoi to live in larger groups in a region previously occupied by the subsistence hunter-gatherers, the San.

Advancing Bantu in the third century had encroached on the Khoikhoi territory, forcing movement into more arid areas.

There has been some intermarriage between migratory Khoi bands living around what is today Cape Town and the San.

However the two groups remain culturally distinct as the Khoikhoi continue to graze livestock and the San to subsist on hunting-gathering.

After friendly trade with the Khoikhoi, some of the crew visit their nearby village, where they try to steal some of the locals' cattle.

Almeida allows his captains Pedro and Jorge Barreto to return to the village on the morning of March 1, 1510.

The village's cattle herd is raided with the loss of one man, while Almeida awaits his men some distance from the beach.

As the flagship's master Diogo d'Unhos moves the landing boats to the watering point, the Portuguese are left without a retreat.

The Khoikhoi sense the opportunity for an attack, during which Almeida and sixty-four of of his men perish, including eleven of his captains.

Almeida's body is recovered the same afternoon and buried on the shore front of the current Cape Town.

Sultan Mahmud Shah, the younger brother of Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah, rules the Sultanate of Malacca from 1488.

Upon his father's premature death, he had been installed at a very young age.

The regent at that time was the prime minister (Bendahara in Malay) Tun Perak.

During his initial years as a young adult, the sultan was known to be a ruthless monarch.

The administration of the sultanate was in the hands of an able and wise Tun Perak.

After the death of Tun Perak in 1498, he was succeeded by a new Prime Minister Tun Mutahir.

The death of Tun Perak is associated with the transformation of Sultan Mahmud into a more responsible ruler.

During Portuguese admiral Diogo Lopes de Sequeira's visit to Malacca from 1509–1510, the sultan had plannned to assassinate him.

However, Sequeira had learned of this plot and fled Malacca.

When the famous Portuguese naval officer Afonso de Albuquerque receives word of this, he decides to utilize this to embark upon his expeditions of conquest in Asia.

Vasco da Gama’s Late Recognition: The First Count of Vidigueira (1519)

After two decades of political sidelining, Vasco da Gama had spent much of his post-exploration life living quietly in Portugal, married and raising a family, largely ignored by King Manuel I despite his historic achievements in opening the sea route to India.

However, by 1518, with Portugal’s growing rivalry with Spain and the defection of Ferdinand Magellan to the Crown of Castile, da Gama’s threat to follow suit forced Manuel to reconsider his neglect of Portugal’s most famous explorer.

Da Gama’s Political Struggles and Sidelining from Indian Affairs

- Since his return from India in 1503, da Gama had been excluded from further Indian expeditions.

- King Manuel I favored other figures, including:

- Francisco de Almeida, the first Viceroy of India (1505–1509).

- Afonso de Albuquerque, the architect of Portuguese imperial expansion in the East (1509–1515).

- Lopo Soares de Albergaria and Diogo Lopes de Sequeira, later commanders in India.

- In 1507, da Gama switched from the Order of Santiago to the Order of Christ, hoping to gain favor with the king, but with little result.

The Magellan Crisis and Manuel’s Fear of Losing Da Gama to Spain (1518)

- In 1518, Ferdinand Magellan defected to Castile, securing Spanish backing for his voyage to circumnavigate the globe.

- When da Gama threatened to do the same, King Manuel I took immediate action to retain his most prestigious admiral.

- Manuel feared the humiliation of losing da Gama to Spain, especially since the Portuguese Crown had already overlooked him for years.

Da Gama Becomes the First Count of Vidigueira (December 29, 1519)

- In Évora, on December 29, 1519, Manuel I granted Vasco da Gama the feudal title of Count of Vidigueira.

- This was a historic appointment, as da Gama became the first Portuguese count not born of royal blood.

- The title was made possible through a complex deal with Dom Jaime, Duke of Braganza, who ceded Vidigueira and Vila dos Frades to da Gama in exchange for payment.

- The decree granted da Gama and his heirs all the revenues and privileges of the countship, making him a true nobleman in the Portuguese aristocracy.

Significance of Da Gama’s Late Recognition

-

A Political Redemption

- After years of neglect, da Gama was finally recognized for his role in Portugal’s maritime expansion.

-

The First Non-Royal Portuguese Count

- His title set a precedent, proving that service to the Crown could be rewarded with nobility.

-

Strengthening His Ties to Portugal

- The grant of land and privileges ensured that da Gama would remain loyal to Portugal, preventing him from following Magellan’s path to Spain.

Conclusion: Da Gama’s Rehabilitation in Portuguese Politics

The creation of the Count of Vidigueira in 1519 marked Vasco da Gama’s return to royal favor, securing his status as a noble and preventing his defection to Spain. Though belated, it was a recognition of his historic contributions, setting the stage for his eventual return to India as Viceroy in 1524, cementing his lasting legacy in Portuguese history.

Vasco da Gama, setting out in April 1524 with a fleet of fourteen ships, had taken as his flagship the famous large carrack Santa Catarina do Monte Sinai on her last journey to India, along with two of his sons, Estêvão and Paulo.

After a troubled journey (four or five of the ships were lost en route), he had arrived in India in September.

Vasco da Gama had immediately invoked his high viceregent powers to impose a new order in Portuguese India, replacing all the old officials with his own appointments, but Gama had contracted malaria not long after arriving, and died in the city of Cochin on Christmas Eve in 1524, three months after his arrival.

As per royal instructions, da Gama is succeeded as governor of India by one the captains who had come with him, Henrique de Menezes (no relation to Duarte).

Vasco's sons Estêvão and Paulo immediately lose their posts and will join the returning fleet of early 1525 (along with the dismissed Duarte de Menezes and Luís de Menezes).

Vasco da Gama's body is first buried at St. Francis Church, which is located at Fort Kochi in the city of Kochi, but his remains will be returned to Portugal in 1539 and his body re-interred in Vidigueira in a casket decorated with gold and jewels.

Vasco da Gama’s Return as Viceroy of India (1524): Reforming Portuguese Strategy in Asia

After the death of King Manuel I in 1521, John III of Portugal undertook a major review of the Portuguese government overseas, aiming to shift strategy away from Manuel’s fixation on Arabia and toward countering the rising Spanish threat in the Maluku Islands (Spice Islands). To achieve this, Vasco da Gama was recalled from political obscurity and appointed Viceroy of Portuguese India in 1524, marking his return to power after two decades of political exile.

John III’s Shift in Strategy and the Fall of Duarte de Menezes

- John III distanced himself from the old Albuquerque faction, which had been influential under Manuel I but was now represented by Diogo Lopes de Sequeira.

- Duarte de Menezes, the then-governor of Portuguese India, was both corrupt and incompetent, drawing numerous complaints.

- Menezes had continued the Manueline focus on controlling Arabia and the Red Sea, which Vasco da Gama strongly opposed.

- Seeing the Spanish expansion in the Maluku Islands as the greater threat, Gama advised a shift in priorities toward Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean spice trade.

Vasco da Gama Appointed Viceroy (February 1524)

- On February 1524, King John III officially appointed Vasco da Gama as the new Viceroy of Portuguese India, making him only the second Portuguese governor to receive this prestigious title (the first was Francisco de Almeida in 1505).

- Gama’s appointment was strategic, as his legendary status and past accomplishments were expected to restore order, stabilize Portuguese rule, and signal a new era of governance in India.

Family Appointments and Political Bargains

- Gama’s second son, Estêvão da Gama, was appointed "Capitão-mor do Mar da Índia", replacing Luís de Menezes as commander of the Indian Ocean fleet.

- As part of his return to favor, Gama secured a commitment from John III to appoint all his sons successively as Portuguese captains of Malacca, ensuring his family’s long-term influence in the empire.

Significance of Vasco da Gama’s Return to India

-

A Strategic Shift Away from Arabia

- Gama’s appointment marked the end of Portugal’s obsession with Arabia and the beginning of a more pragmatic focus on controlling the Indian Ocean spice trade.

-

A Purge of Corrupt Officials

- As viceroy, Gama was expected to clean up the corruption left by Duarte de Menezes, restoring discipline and efficiency in the Portuguese administration.

-

A Lasting Gama Dynasty in the East

- By securing his sons’ appointments in Malacca, Gama ensured that his family would maintain influence in Portuguese Asia even after his death.

Conclusion: Gama’s Final Mission

At age 64, Vasco da Gama’s return to power in 1524 was both a redemption and a final opportunity to shape the future of Portuguese India. However, his second governorship would be short-lived, as he would die in Cochin later that year, leaving behind a restructured Portuguese strategy and a lasting family legacy in the East.