Bartolomeu Dias

Portuguese explorer

Years: 1451 - 1500

Bartolomeu Dias (Anglicized: Bartholomew Diaz; c. 1451 – May 29, 1500[=, a nobleman of the Portuguese royal household, was a Portuguese explorer.

He sails around the southernmost tip of Africa in 1488, reaching the Indian Ocean from the Atlantic, the first European known to have done so.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 30 total

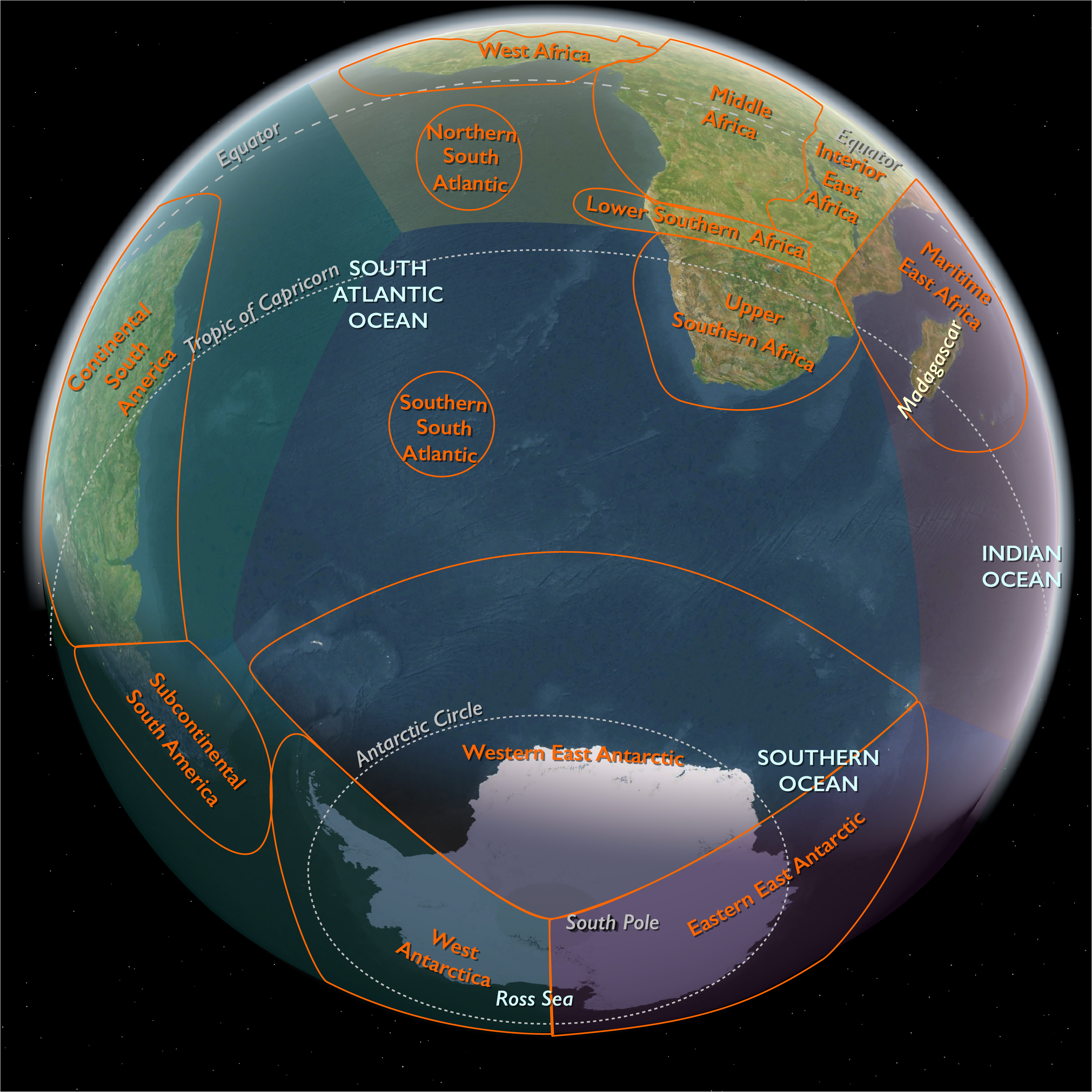

Southern Africa (1396–1539 CE)

Fynbos Shores, Karoo Uplands, and Delta Wetlands

Geography & Environmental Context

Southern Africa comprised two contrasting temperate and tropical subregions.

Temperate Southern Africa spanned the Cape Fold Belt, the Karoo basins, the Highveld plateau, and the Drakensberg–Lesotho escarpment, extending north into southern Zimbabwe and southwestern Mozambique.

Tropical West Southern Africa encompassed the Etosha Pan, the Okavango Delta, the Chobe–Linyanti–Kwando corridor, the Caprivi–Upper Zambezi basin, and the Skeleton Coast.

Together these landscapes joined winter-rain fynbos, semi-arid steppe, and inland floodplains—the ecological bridge between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The onset of the Little Ice Age brought cooler winters and heightened variability.

-

Cape & Namaqualand: Alternating wet winters and multi-year droughts; frost frequent in inland valleys.

-

Karoo & Kalahari: Increased aridity punctuated by flash floods.

-

Highveld & southern Zimbabwe: Summer rainfall punctuated by droughts; frosts common in winter.

-

Drakensberg–Lesotho: Snow on summits, hail and summer storms.

-

Okavango & Chobe: Regular flood pulses from the upper Zambezi sustained wetlands even in dry years.

-

Skeleton Coast: Persistent aridity offset by fog moisture supporting desert flora and fauna.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Cape herders (Khoekhoen): Practiced cattle- and sheep-herding transhumance between coastal plains and inland pans; kraals located near rivers and salt licks.

-

San foragers: Hunted antelope and zebra with bow and poison; gathered bulbs, fruits, and shellfish; rock shelters preserved seasonal camps.

-

Highveld & southern Zimbabwe farmers: Cultivated sorghum, millet, and beans; raised cattle as wealth and ritual currency; clustered villages with stone enclosures and grain bins reflected the Khami cultural horizon.

-

Southern Kalahari & Karoo: Mixed herding and foraging along pans and ephemeral rivers.

-

Southwestern Mozambique: Sorghum–millet–rice farming with cattle herding; linked indirectly to Indian Ocean traders at Sofala.

-

Northern Namibia & Botswana: Agro-pastoral Ovambo, Kavango, and Tswana groups farmed millet and sorghum, grazed cattle and goats, and used floodplains seasonally.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Khoekhoen: Skin cloaks, milk pails, hide bags, bead ornaments, kraal fencing.

-

San: Ostrich-eggshell beads, bone arrowpoints, stone scrapers, and painted rock panels.

-

Agro-pastoralists: Iron hoes, spears, and pottery; stone-walled homesteads, cattle byres, and woven mats; copper and gold from southern Zimbabwe traded north.

-

Fisheries: Stone tidal traps and basket nets along the Cape coast; dugout canoes in the Okavango.

-

Foragers of the Skeleton Coast: Crafted shell ornaments, leather water bags, and wooden digging sticks adapted to arid survival.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Cape transhumance: Seasonal shifts through the Berg–Breede–Olifants valleys.

-

Highveld–Zimbabwe trade: Grain, livestock, copper, and gold linked southern chiefdoms with Great Zimbabwe’s waning network.

-

Drakensberg–Lesotho shelters: Ritual and hunting stations adorned with rock art.

-

Okavango–Chobe–Caprivi: Wet-season canoe routes joined fishing and farming zones.

-

Etosha–Ovambo plains: Grain and stock exchanges connected floodplain villages.

-

Early European contact: Bartolomeu Dias (1488) rounded the Cape; Vasco da Gama (1497–98) anchored at Mossel Bay, marking the first coastal encounters with herders.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

San rock art: Rain-animals, therianthropes, and trance dances in the Cederberg, Drakensberg, and Matobo Hills.

-

Khoekhoen: Cattle feasts, cairn offerings, herd naming, and ancestor invocations.

-

Bantu-speaking farmers: Rainmaking, initiation, and ancestor veneration integrated crop cycles with cattle ritual.

-

Floodplain societies: Cattle feasts and rain-calling ceremonies celebrated seasonal renewal.

-

Forager cosmologies: Along the Skeleton Coast, mythic beings embodied the struggle between sea, fog, and desert.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Mobility: Herd movement between seasonal pastures prevented overuse; San groups shifted hunting ranges and stored dried meat and fish.

-

Storage: Grain bins and ostrich-eggshell caches preserved reserves; dried fish and meat carried communities through drought.

-

Diversification: Farmers intercropped legumes, rotated fields, and relied on cattle loans and reciprocity to cushion scarcity.

-

Floodplain adaptation: Villages relocated seasonally; millet and sorghum sown on receding waters; fisheries maintained protein security.

-

Arid-coast survival: Foragers exploited fog vegetation, seals, and seabirds; desert knowledge ensured continuity.

Technology & Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

-

Local contests: Stock raiding between herders and hunters; village disputes over water and grazing.

-

Regional hierarchies: The Khami polity rose as Great Zimbabwe declined, drawing livestock and goods from southern chiefdoms.

-

Trade links: Cattle and ivory moved north; beads, iron, and cloth filtered south.

-

European intrusion: Portuguese explorers placed stone padrões along the Cape but made no inland incursions; first exchanges of trinkets and livestock occurred on the coast.

Transition (to 1539 CE)

By 1539 CE, Southern Africa sustained a mosaic of lifeways:

Mobile Khoekhoen herders ranged the Cape; San foragers painted trance visions across upland rock; Nguni, Sotho–Tswana, and southern Shona farmers built stone-walled settlements on the Highveld and Lesotho rim; floodplain peoples along the Okavango and Chobe wove fishing and herding into one cycle.

Portuguese ships had rounded the Cape and skirted the coast, yet inland societies remained autonomous.

The region’s enduring balance of mobility, diversification, and ritual stewardship carried its peoples securely into the early modern age soon to follow.

Temperate Southern Africa (1396–1539 CE): Fynbos Shores, Karoo Uplands, and Plateau Homesteads

Geographic & Environmental Context

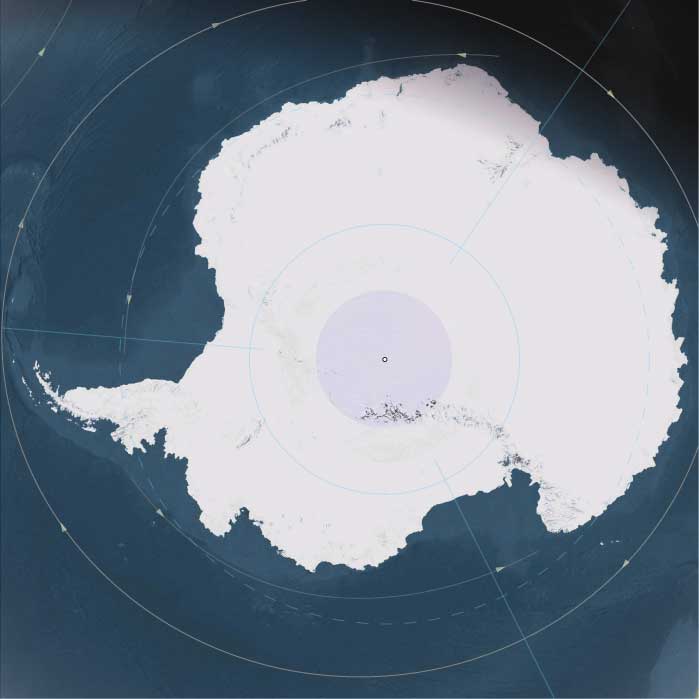

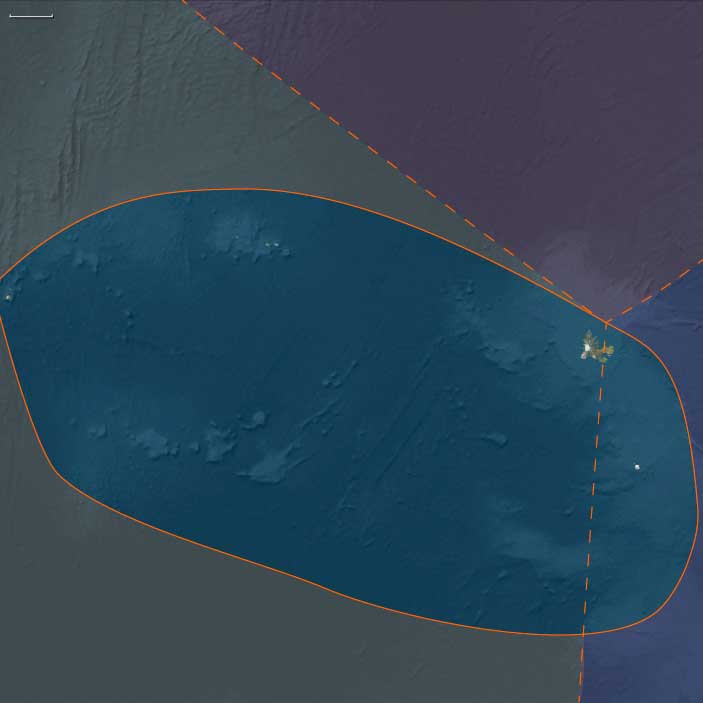

The subregion of Temperate Southern Africa includes all of the Republic of South Africa, Lesotho, and Eswatini; Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe south of ~19.47°S; and the adjoining temperate corridor of southwestern Mozambique. Anchors spanned the Cape Fold Belt (fynbos and renosterveld, Berg, Breede, Gouritz rivers, Agulhas Plain), Namaqualand and the Orange River mouth, the semi-arid Karoo basins, the Highveld plateau and Bushveld interior, the Drakensberg–Lesotho escarpment (including Eswatini’s foothills), the southern Kalahari(Botswana–Namibia margins), the southern Zimbabwe plateau south of the Tokwe and Save rivers, and the Limpopo–Inhambane corridor in southwestern Mozambique.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

During the Little Ice Age, cooler winters and greater variability prevailed:

-

Cape & Namaqualand: winter-rain pulses punctuated by multi-year droughts; frost in valleys.

-

Karoo & Kalahari margins: heightened aridity, occasional floods after cloudbursts.

-

Highveld & southern Zimbabwe: summer rainfall with occasional droughts; frosts in winter.

-

Drakensberg–Lesotho: snow on summits, hail and storms in summer.

-

Southwest Mozambique: monsoon-fed summer rains, variable but sufficient for farming.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Cape herders (Khoekhoen): Cattle and sheep transhumance between coast and inland pans; kraals near rivers and salt licks.

-

San foragers: Bow-and-poison hunting of antelope, eland, zebra; gathering bulbs, fruits, and shellfish along coastlines.

-

Highveld & southern Zimbabwe farmers: Sorghum, millet, beans, gourds in terraced and alluvial fields; cattle central to wealth and social status; village clusters with grain bins and stone enclosures.

-

Southern Kalahari & Karoo: Forager–herder overlap; sheep herding along pans, game hunting, and wild fruit collection.

-

Southwest Mozambique: Agro-pastoral villages along rivers; mixed sorghum–millet–rice farming and cattle husbandry.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Khoekhoen: Milk pails, skin bags, kraal fencing, hide cloaks, beadwork.

-

San: Ostrich eggshell beads, bone arrowpoints, stone scrapers, rock paintings.

-

Farming peoples (Nguni, Sotho–Tswana, southern Shona): Iron hoes, spears, pottery, stone-walled homesteads (e.g., Khami influence extending into southern Zimbabwe), cattle byres, woven mats.

-

Marine adaptations: Stone tidal traps, basket fishing, seal hunting.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Cape transhumance routes: Berg–Breede–Olifants valleys.

-

Drakensberg–Lesotho shelters: Hunting–ritual nodes and painting sites.

-

Highveld–southern Zimbabwe exchange: Cattle, grain, and metals circulated; copper and gold moved north to Great Zimbabwe’s orbit, with southern chiefdoms contributing livestock and food.

-

Southwest Mozambique corridors: Linked Limpopo farmers to Indian Ocean traders at Sofala, though influence was indirect.

-

Early European contact: Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape (1488); Vasco da Gama made landfall at Mossel Bay (1497–98). Cautious barter and skirmishes occurred with herders.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

San rock art: Rain animals, therianthropes, and trance dances across Cederberg, Drakensberg, Matobo Hills (southern Zimbabwe).

-

Khoekhoen: Cattle feasts, cairn offerings, and herd-naming traditions.

-

Highveld & southern Zimbabwe: Ancestor veneration, rainmaking rituals, initiation ceremonies tied to cattle and crop cycles.

-

Mozambique–Limpopo farmers: Ritual beer feasts, spirit-mediumship, and shrines linked to Indian Ocean trade goods (beads, cloth).

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Herders diversified stock (sheep/cattle), trekked flexibly between pastures, and relied on shellfish during drought.

-

San hunter-gatherers broadened prey and stored meat/fish; ostrich eggshell caches preserved water.

-

Farmers rotated crops, intercropped legumes, and managed terraces.

-

Grain storage bins and reciprocal cattle loans buffered shortages.

Technology & Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

-

Local tensions: Stock raiding between herders and hunters; disputes between villages over grazing and water.

-

Regional powers: Southern Zimbabwe fell within the shifting sphere of Great Zimbabwe’s waning influence and Khami’s rise (15th–16th c.).

-

First European probes: Dias and da Gama marked the coastline with padrões; no permanent impact inland but first written notices of herder encounters.

Transition

By 1539 CE, Temperate Southern Africa combined mobile Khoekhoen herders, San foragers, and settled agro-pastoral communities on the Highveld, Lesotho, Eswatini, southern Zimbabwe, and southwestern Mozambique. The Portuguese had rounded the Cape and probed the coast, but inland lifeways continued largely intact.

Two ships under Bartholomeu Dias eventually round the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 and travel more than six hundred kilometers along the southwestern coast.

An expedition under Vasco da Gama rounds the Cape in 1497, sails up the east African coast to the

Arab port of Malindi (in present-day Kenya), then crosses the Indian Ocean to India, thereby opening up a way for Europeans to gain direct access to the spices of the East without having to go through Arab middlemen.

The Portuguese dominate this trade route throughout the sixteenth century.

They build forts and supply stations along the west and east African coasts, but they do not build south of present-day Angola and Mozambique because of the treacherous currents along the southern coast.

Portugal's crown during the reign of Joao II once again takes an active role in the search for a sea route to India.

In 1481 the king orders a fort constructed at Mina de Ouro to protect this potential source of wealth.

Diogo Cão sails farther down the African coast in the period 1482-84.

A new expedition in 1487 led by Bartolomeu Dias sails south beyond the tip of Africa and, after having lost sight of land for a month, turns north and makes landfall on a northeast-running coastline, which is named Terra dos Vaqueiros after the native herders and cows that are seen on shore.

Dias has rounded the Cape of Good Hope without seeing it and has proven that the Atlantic connects to the Indian Ocean.

Bartolomeu Dias is a Knight of the royal court, superintendent of the royal warehouses, and sailing-master of the man-of-war, São Cristóvão (Saint Christopher).

King John II of Portugal appoints him, on October 10, 1487, to head an expedition to sail around the southern tip of Africa in the hope of finding a trade route to India.

Dias is also charged with searching for the lands ruled by Prester John, a fabled Christian priest and ruler.

Dias' ship São Cristóvão is piloted by Pêro de Alenquer.

A second caravel, the São Pantaleão, is commanded by João Infante and piloted by Álvaro Martins.

The expedition sails south along the West coast of Africa.

Extra provisions are picked up on the way at the Portuguese fortress of São Jorge de Mina on the Gold Coast.

After having sailed past Angola, Dias reaches the Golfo da Conceicão (Walvis Bay) by December.

Continuing south, he discovers first Angra dos Ilheus, being hit, then, by a violent storm.

Thirteen days later, from the open ocean, he searches the coast again to the east, discovering and using the westerly winds—the ocean gyre, but finding just ocean.

Having rounded the Cape of Good Hope at a considerable distance to the west and southwest, he turns towards the east, and taking advantage of the winds of Antarctica that blow strongly in the South Atlantic, he sails northeast.

After thirty days without seeing land, he enters what he names Aguada de São Brás (Bay of Saint Blaise)—later renamed Mossel Bay—on February 4, 1488.

Dias's expedition reaches its furthest point on March 12, 1488, when they anchor at Kwaaihoek, near the mouth of the Bushman's River, where a padrão—the Padrão de São Gregório—is erected before turning back.

Dias wants to continue sailing to India, but he is forced to turn back when his crew refuses to go further.

It is only on the return voyage that he actually discovers the Cape of Good Hope, in May 1488.

Dias names the promontory the Cape of Storms, but King John will soon rename it the Cape of Good Hope after the riches of Asia that begin flowing around it to Portugal.

King John II had put Pêro da Covilhã in charge of diverse private missions, and finally, to use his knowledge of different languages, orders him and Afonso de Paiva to undertake a mission of exploration in the Near East and the adjoining regions of Asia and Africa, with the special assignment to learn where cinnamon and other spices can be found, as well as of discovering the land of legendary Prester John, by overland routes.

Bartolomeu Dias, at the same time, goes out to by sea find the Prester's country, as well as the termination of the African continent and the ocean route to India.

The expedition starts at Santarém, on May 7, 1487.

Covilhã and Paiva are provided with a letter of credence for all the countries of the world and with a map for navigating, taken from the map of the world and compiled by Bishop Diogo, and doctors Rodrigo and Moisés.

The first two of these were prominent members of the commission that had advised the Portuguese government to reject the proposals of Christopher Columbus.

The explorers start from Santarém and travel by Barcelona to Naples, where their bills of exchange are paid by the sons of Cosimo de' Medici; from here they go to Rhodes, where they stay with two other Portuguese, and so to Alexandria and Cairo, where they pose as merchants.

In company with Arabs from Fez and Tlemcen, they now go by way of El-Tor in the southern Sinai Peninsula to the port of Suakin on the west coast of the Red Sea, then cross to Aden, where, as it is now the monsoon, the two expedition leaders part.

Covilhã proceeds to India and Paiva to Ethiopia.

They agree to meet again in Cairo.

Atlantic Southwest Europe (1480–1491 CE): Portugal’s Maritime Empire and Cultural Golden Age, Castilian Consolidation under Isabella and Ferdinand, and Navarrese Diplomatic Challenges

Between 1480 and 1491 CE, Atlantic Southwest Europe—including Galicia, northern and central Portugal, Asturias, Cantabria, and northern Spain south of the Franco-Spanish border (43.05548° N, 1.22924° W)—entered a period of remarkable transformation. Portugal, under King João II (1481–1495 CE), reached a golden age marked by extensive maritime exploration, global commerce, and Renaissance cultural flourishing. Castile, decisively governed by the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragón, achieved political consolidation, administrative centralization, and cultural renewal. Navarre faced diplomatic challenges as it navigated tensions between France, Castile, and Aragón. Collectively, these developments significantly shaped regional identities, economic prosperity, and intellectual innovation, setting the stage for the Iberian Peninsula’s global prominence.

Political and Military Developments

Portugal’s Golden Age under João II

Following Afonso V’s reign, King João II (1481–1495 CE) decisively expanded Portugal’s maritime empire. João II intensified exploration, with Portuguese navigators, notably Diogo Cão (1482–1486) and Bartolomeu Dias (1487–1488), achieving landmark voyages—Dias famously rounding the Cape of Good Hope (1488). João II strengthened royal authority, curbing noble power, and established a centralized, efficient administration capable of managing a global maritime empire. These developments decisively set the stage for Portugal’s subsequent global ascendancy.

Castilian Consolidation under Isabella and Ferdinand

Castile experienced significant consolidation under the assertive rule of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I (1474–1504 CE) and Ferdinand II (1479–1516 CE). They decisively stabilized governance structures, curtailed noble factionalism, and reformed administrative and judicial systems. In 1481, they began the decisive final phase of the Reconquista, targeting the Emirate of Granada. Their reign profoundly reshaped Castilian political identity, administrative coherence, and civic stability.

Navarrese Diplomatic Challenges and Autonomy

Navarre, under Queen Catherine I (1483–1517 CE), faced diplomatic complexities amidst competing Castilian, Aragonese, and French interests. Despite internal tensions, Catherine maintained Navarrese territorial autonomy and diplomatic neutrality through pragmatic governance, cautious diplomacy, and strategic marriage alliances, preserving Navarre’s stability amid broader Iberian geopolitical upheavals.

Economic Developments

Agricultural Prosperity and Economic Stability

Agricultural productivity decisively remained strong, bolstered by diversified crops—including grains, vineyards, olives, citrus fruits, almonds—and robust livestock production. Regional mining of gold and silver (particularly in Galicia and Asturias) significantly supported economic resilience and demographic stability.

Expansion of Portuguese Maritime Trade and Global Commerce

Portuguese maritime commerce reached a golden era under João II, with Lisbon decisively becoming a pivotal European trading center. Expanded African trade, emerging trade routes toward India and Asia, and established Atlantic island commerce dramatically boosted Portuguese economic prosperity. Galicia’s ports, particularly A Coruña, benefited from increased maritime traffic and trade, enhancing regional economic resilience.

Pilgrimage Economy and Cultural Exchange in Galicia

Pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela decisively supported sustained economic vitality, enhancing hospitality industries, artisanal commerce, infrastructure projects, and cultural exchanges. Persistent pilgrimage significantly reinforced Galicia’s economic resilience, cultural prominence, and international recognition.

Cultural and Religious Developments

Portuguese Renaissance Golden Age

Portugal decisively entered its cultural Renaissance golden age under João II. Influenced by humanist contacts with Italy and northern Europe, Portugal fostered significant advances in literature, cartography, navigational science, architecture, and education. Major intellectual figures and institutions flourished, with courtly patronage significantly boosting scholarly achievements and artistic creativity, profoundly shaping Portugal’s intellectual identity.

Castilian Cultural Renewal and Humanist Scholarship

Castilian culture flourished decisively under Isabella and Ferdinand, enriched by significant Renaissance humanist influences, notably from Italy. The monarchs patronized literature, educational reform, architecture, and art, encouraging early Renaissance intellectual revival. Castilian universities and literary circles benefited significantly from scholarly exchanges, decisively laying foundations for Spain’s mature Renaissance culture.

Galician Cultural Resilience and Ecclesiastical Patronage

Galicia decisively maintained cultural prominence, supported by Santiago de Compostela’s ecclesiastical institutions and monastic communities. Scholarship, manuscript preservation, artistic patronage, and significant architectural endeavors continued, reinforcing Galicia’s cultural identity and international reputation.

Persistent Cultural Syncretism and Local Traditions

Orthodox Christianity consistently integrated indigenous Iberian and Celtic traditions, particularly in rural Galicia and northern Portugal. Persistent cultural syncretism decisively reinforced regional identities, social cohesion, and cultural resilience during this transformative era.

Civic Identity and Governance

Portuguese Civic Unity and Global Ambitions

Portugal decisively reinforced civic unity, national identity, and governance stability under João II. Maritime exploration significantly shaped Portuguese collective ambitions, laying critical foundations for global empire-building, economic prosperity, and cultural prominence.

Castilian Civic Identity and Administrative Consolidation

Under Isabella and Ferdinand, Castile decisively consolidated civic identity, territorial integrity, and administrative reforms. Effective governance significantly shaped Castilian political stability, regional identity, and early Renaissance cultural renewal.

Navarrese Regional Autonomy and Diplomatic Stability

Navarre decisively preserved regional autonomy, diplomatic neutrality, and internal governance coherence under Catherine I. Her pragmatic diplomacy significantly maintained territorial integrity, regional stability, and northern Iberian geopolitical coherence.

Notable Regional Groups and Settlements

-

Portuguese: Experienced decisive maritime expansion, global economic prosperity, and Renaissance cultural flourishing under João II, significantly shaping Portugal’s historical trajectory and future global influence.

-

Castilians: Consolidated governance stability, territorial integrity, and cultural renewal under Isabella and Ferdinand, significantly influencing Iberian political, intellectual, and cultural developments.

-

Galicians: Sustained vibrant economic resilience, cultural vitality, and ecclesiastical prominence, significantly reinforced by pilgrimage activity and maritime commerce.

-

Basques (Navarre): Maintained regional autonomy, diplomatic neutrality, and stable governance under Catherine I, significantly shaping northern Iberian political coherence.

Long-Term Significance and Legacy

Between 1480 and 1491 CE, Atlantic Southwest Europe:

-

Reached the pinnacle of Portuguese maritime dominance, global economic expansion, and Renaissance cultural flourishing, decisively setting foundations for Portugal’s subsequent global empire and intellectual prominence.

-

Experienced significant Castilian political consolidation, administrative centralization, and cultural renewal under Isabella and Ferdinand, profoundly shaping Iberian unity and setting key foundations for the mature Spanish Renaissance.

-

Navigated diplomatic complexities in Navarre under Catherine I, significantly influencing northern Iberian geopolitical coherence and regional stability.

-

Maintained agricultural prosperity, expanded global maritime commerce, pilgrimage-driven economic stability, and vibrant cultural renewal, profoundly shaping regional historical trajectories.

This transformative era decisively shaped regional identities, governance structures, economic continuity, cultural resilience, and intellectual foundations, profoundly influencing Atlantic Southwest Europe’s trajectory toward the Iberian Renaissance and global prominence.

Atlantic Southwest Europe: Unification, Exploration, and Cultural Flowering (1480–1491)

From 1480 to 1491, Atlantic Southwest Europe underwent profound political transformations, economic advancements, and cultural renewal. The marriage and joint rule of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile initiated the consolidation of the Spanish kingdoms, while Portugal, under João II, reached new heights of maritime exploration and global influence. Navarre struggled politically but retained its distinct identity, caught between growing Spanish and French interests.

Political and Military Developments

-

Castile and León (including Northern territories):

- The joint monarchy of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon (r.1474–1504 and 1479–1516 respectively) effectively unified most of Iberia through the completion of the Reconquista with the conquest of Granada in 1492.

- In the north, the Basque provinces, Galicia, and northern Rioja gradually integrated into the expanding Castilian-Aragonese state, yet maintained considerable autonomy through the reaffirmation of traditional fueros (regional laws).

-

Portugal:

- João II (r. 1481–1495), known as the "Perfect Prince," consolidated royal authority, curtailed noble power, and modernized the Portuguese administration. His rule marked a significant centralization of power and efficiency.

- Militarily, João secured key Atlantic outposts and negotiated crucial treaties, such as the Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo (1479–1480) with Castile, stabilizing Portuguese territorial claims and allowing further maritime expansion.

-

Navarre:

- Navarre remained internally divided and politically vulnerable, navigating carefully between Castilian-Aragonese ambitions and French influence.

- The rule of Queen Catherine of Foix (r. 1483–1517) was marked by dynastic fragility and diplomatic balancing, seeking to preserve Navarre’s sovereignty amid growing external pressures.

Economic and Maritime Expansion

-

Portuguese Maritime Achievements:

- Under João II, Portugal greatly expanded its exploration, notably through voyages led by Bartolomeu Dias, who rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, dramatically opening the route to the Indian Ocean.

- These maritime successes cemented Lisbon's position as a global trading hub, significantly boosting the economy and financing further voyages.

-

Economic Integration in Northern Spain:

- Increasing stability under Ferdinand and Isabella revitalized trade in northern Castile, Galicia, and Basque ports, particularly Bilbao and Santander, benefiting from rising wool exports and shipbuilding industries.

- Coastal cities leveraged the Atlantic trade networks, exporting iron, wool, and agricultural products, which enhanced regional prosperity despite heavy royal taxation.

-

Navarre’s Strategic Economy:

- Despite political instability, Navarre maintained a critical position as a trading crossroads between the Iberian Peninsula and France, facilitating economic resilience, particularly in wine trade and agriculture.

Cultural and Social Developments

-

Portuguese Renaissance Flourishes:

- João II’s court attracted intellectuals, astronomers, and mapmakers, fostering the emergence of a Portuguese Renaissance culture that supported extensive scientific exploration and cartographic advancements.

- Lisbon became a leading European center of learning, attracting international scholars who contributed to a rich cultural exchange.

-

Spain’s Cultural Unity and Expansion:

- Ferdinand and Isabella vigorously promoted religious uniformity, culminating in the establishment of the Spanish Inquisition (1478), which had profound social implications across northern Castile and Galicia, although Basque regions largely maintained their traditions.

- The founding of the University of Santiago de Compostela (1495), planned during this period, signified Galicia’s growing cultural prominence.

-

Navarrese Identity and Autonomy:

- Navarre continued nurturing its distinct identity, preserving its autonomous institutions, legal customs, and cultural traditions amid external pressures.

Significance and Legacy

The years 1480–1491 marked a pivotal era for Atlantic Southwest Europe, laying foundations for global imperial competition, especially through Portuguese maritime exploration and Castilian-Aragonese consolidation. Portugal's maritime triumphs under João II opened trade routes that transformed global economics. Simultaneously, the unification of Spain under the Catholic Monarchs profoundly shaped the region's political future. Navarre’s precarious yet resilient existence underscored the complexities of European dynastic politics. Culturally, the period witnessed the blossoming of Renaissance ideas, marking a crucial transition to modernity for the region.

This fleet is commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral and includes Bartolomeu Dias, various nobles, priests, and some twelve hundred men of Portugal.

The fleet sails southwest for a month, and on April 22 sights land, the coast of present-day Brazil.

Cabral sends a ship back to Lisbon to report to Manuel his discovery, which he calls Vera Cruz.

The fleet recrosses the Atlantic and sails to India around Africa, where it arrives on September 13, 1500.

After four months in India, Cabral sails for Lisbon in January 1501, having left a contingent of Portuguese to maintain a factory at Cochin on the Malabar coast.

King João meanwhile sends Pêro da Covilhã and Afonso de Paiva, who ware versed in warfare, diplomacy, and Arabic, on a mission in search of the mythical Christian kingdom of Prester John.

Departing from Santarém, they travel to Barcelona, Naples, and the island of Rhodes, and, disguised as merchants, enter Alexandria.

Passing through Cairo, they make their way to Aden, where they separate and agree to meet later in Cairo at a certain date.

Afonso de Paiva goes to Ethiopia, and Pero da Covilha heads for Calicut and Goa in India by way of Ormuz, returning to Cairo via Sofala in Mozambique on the east coast of Africa.

In Cairo he learns from two emissaries sent by Joao II that Afonso de Paiva has died.

One of the emissaries returns to Portugal with a letter containing the information Pêro da Covilhã had collected on his travels.

Covilhã then leaves for Ethiopia where he is received by the emperor but not allowed to leave.

He settles in Ethiopia, marries, and raises a family.

The information provided in his letter complements the information from the expedition of Bartolomeu Dias and persuades João II that it is possible to reach India by sailing around the southern end of Africa.

He dies during preparations for this voyage in 1494.