Western West Indies (820 – 963 CE): …

Years: 820 - 963

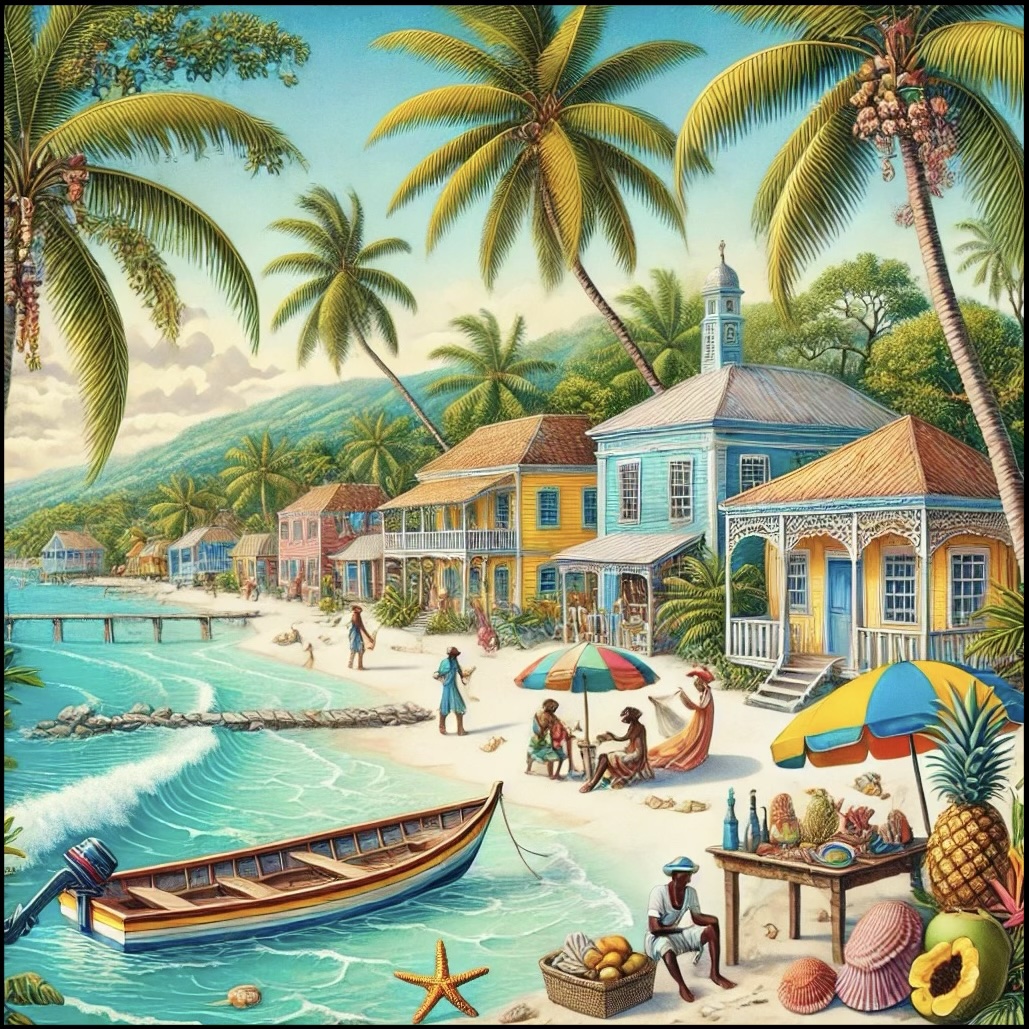

Western West Indies (820 – 963 CE): Ostionoid Settlements, Canoe Corridors, and the Western Gateways

Geographic and Environmental Context

The Western West Indies includes Cuba and its surrounding islands, Jamaica, the Cayman Islands, and western Haiti — including Tortuga Island, the Massif du Nord’s western flank, the Gonâve Gulf and Peninsula, and Port-de-Paix as its principal coastal node.

-

Cuba, the largest island in the Caribbean, offered broad alluvial plains (notably in the west and central valleys), karst uplands, and extensive coastlines.

-

Jamaica provided fertile volcanic soils and mountain-fed rivers.

-

Western Haiti, with the Massif du Nord, Gonâve Gulf, and Tortuga, was a crossroads between Hispaniola’s interior valleys and the northern Caribbean sea-lanes.

-

The Caymans, smaller and reef-fringed, offered turtle-rich waters but few permanent settlements in this early period.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Tropical maritime climate, moderated by trade winds, with abundant rainfall in Cuba and Jamaica.

-

Western Hispaniola’s rainfall was variable, with fertile pockets along rivers and more arid rain-shadow zones.

-

Hurricanes periodically struck the northern coasts, shaping settlement dispersal.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Populations belonged to the Ostionoid cultural horizon, precursors to the Taíno.

-

Settlement was organized into hamlets of bohíos with incipient plazas, typically sited on river terraces and coastal flats.

-

Western Haiti (around Port-de-Paix, Tortuga, and the Massif du Nord) served as a canoe embarkation point to Cuba and Jamaica, making it a cultural hinge.

-

Cuba was still sparsely populated in its western reaches but saw growing Ostionoid presence in river valleys.

-

Jamaica’s first substantial Ostionoid settlements appeared in this age, linking it directly to Hispaniola and Cuba.

-

Political organization remained kin-based, with leadership vested in village elders rather than hereditary caciques.

Economy and Trade

-

Conuco horticulture in Cuba, Jamaica, and western Hispaniola produced cassava, sweet potato, beans, peppers, and peanuts.

-

Fishing and hunting: reef and lagoon harvests, turtles, manatees, birds, and small game.

-

Canoe-borne exchange:

-

Western Hispaniola exported cassava bread, stone celts, and cotton thread.

-

Cuba provided hardwoods, shell artifacts, and fertile conuco produce.

-

Jamaica contributed timber, feathers, and small quantities of cassava.

-

Caymans served primarily as turtle-fishing stations within this circuit.

-

Subsistence and Technology

-

Cassava processing used griddles and presses to remove toxins, yielding transportable bread.

-

Conucos (raised-mound fields) enhanced soil fertility.

-

Fishing technology: traps, nets, shell/bone hooks.

-

Canoes: dugouts, some large enough for dozens of paddlers, enabling crossings between Cuba, Jamaica, and Hispaniola.

-

Ceramics: Ostionoid red-on-buff wares with simple incised designs, transitioning toward Meillacoid styles.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Windward Passage: linked western Hispaniola and eastern Cuba.

-

Jamaica Channel: tied Cuba to Jamaica through western Hispaniola nodes.

-

Old Bahama Channel: indirectly connected Cuba and Tortuga with the northern Bahamian banks.

-

Cayman waters: seasonal resource zones within the larger canoe network.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Animist traditions honored zemí spirits of rivers, caves, and fertility.

-

Ritual caves in Cuba and Haiti housed offerings of shell and stone.

-

Ancestor veneration: burials included shell ornaments and ochre.

-

Early ritual seats and carved stones foreshadowed the ceremonial life of later Taíno chiefdoms.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Dual economies: root-crop horticulture plus reef/turtle harvests buffered communities against storms.

-

Dispersed settlement along multiple coastal nodes reduced vulnerability to hurricanes.

-

Archipelagic exchange ensured that shortages in one zone (e.g., arid Haiti) could be offset by imports from Cuba or Jamaica.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, the Western West Indies had emerged as a canoe crossroads:

-

Western Hispaniola (Port-de-Paix, Tortuga) acted as the hinge between Cuba, Jamaica, and Hispaniola’s north.

-

Cuba and Jamaica saw Ostionoid expansion of conuco horticulture and ritual cave use.

-

Inter-island exchange was consolidating the cultural and economic web that would mature into Taíno cacicazgos by the 11th–12th centuries.