West Polynesia (964 – 1107 CE): Tuʻi …

Years: 964 - 1107

West Polynesia (964 – 1107 CE): Tuʻi Tonga Hegemony, Samoan Councils, and the Rise of Taputapuātea

Geographic and Environmental Context

West Polynesia includes the Big Island of Hawaiʻi, Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu, Tokelau, the Cook Islands, and French Polynesia (Society Islands and Marquesas).

-

High volcanic islands (Tonga, Samoa, Societies, Marquesas) provided fertile soils for intensive horticulture and supported monumental temple-building.

-

Atolls (Tokelau, Tuvalu, northern Cooks) remained resource-scarce, requiring arboriculture, reef fishing, and long-distance ties for resilience.

-

The Big Island of Hawaiʻi remained geographically peripheral but continued gradual population and chiefly consolidation.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

The Medieval Warm Period (c. 950–1250 CE) brought slightly warmer, more stable conditions in the Pacific, strengthening crop reliability and lengthening sailing seasons.

-

Cyclones still periodically disrupted atoll communities, but surplus redistribution through exchange networks cushioned impacts.

Societies and Political Developments

Tonga

-

The Tuʻi Tonga dynasty consolidated power, extending political and ritual authority beyond Tonga into Samoa, Fiji, and the Cook Islands.

-

Tonga’s expansion marked the first regional Polynesian thalassocracy, uniting island groups under dynastic marriage alliances, tribute systems, and shared ritual frameworks.

-

Large-scale earthworks and elite burials (langi tombs) symbolized dynastic power.

Samoa

-

Power remained distributed among extended kin-groups and councils of matai (chiefs).

-

Samoan institutions—lineage balance, oratory, fine mats (ʻie tōga) as ritual wealth—served as a cultural model for neighboring archipelagos.

-

While not politically unified like Tonga, Samoa wielded immense cultural influence through marriage, ritual exchange, and migration.

Society Islands

-

Taputapuātea marae on Ra‘iātea emerged as a pan-Polynesian ritual and political center, attracting chiefs and priests from across Polynesia to perform alliance-building rituals.

-

The marae created a sacred diplomatic network binding Societies, Cooks, Marquesas, and Tuamotus in shared cult practices.

Marquesas

-

Intensified chiefdom competition led to larger meʻae ceremonial sites and expanded artistic expression in tattooing, wood carving, and ritual stonework.

-

Chiefs legitimized power through alliances with Society Islands cult centers.

Cook Islands, Tokelau, Tuvalu

-

Smaller island chiefdoms incorporated into Tongan and Society networks through marriage and ritual ties.

-

Exchanges with Samoa remained crucial for survival on resource-scarce atolls.

Hawaiʻi (Big Island)

-

Hawaiian society continued gradual growth; irrigation of taro fields expanded in Kona and Hilo, and chiefly lineages gained strength.

-

Hawaiian polities were still localized compared to the hierarchical systems emerging further south.

Economy and Trade

-

Agriculture: intensification of irrigated taro and yam cultivation in high islands; breadfruit and coconut groves sustained atolls.

-

Animal husbandry: pigs, dogs, and chickens supported chiefly feasts and exchanges.

-

Maritime exchange networks: Tonga’s expansion and Taputapuātea’s ritual ties created a dual system of political and religious integration across West Polynesia.

-

Prestige goods: Samoan fine mats, Tongan barkcloth, Society Islands basalt adzes, and Marquesan carvings circulated widely.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Irrigated taro pondfields expanded in Samoa, Societies, and Hawaii.

-

Stone terracing and arboriculture enhanced soil productivity.

-

Fishponds and reef management systems advanced in Hawaii and Tonga.

-

Double-hulled voyaging canoes with crab-claw sails carried chiefs and priests to Taputapuātea and across the Tongan maritime empire.

-

Navigation relied on star compasses, ocean swells, bird routes, and oral transmission of sea-lore.

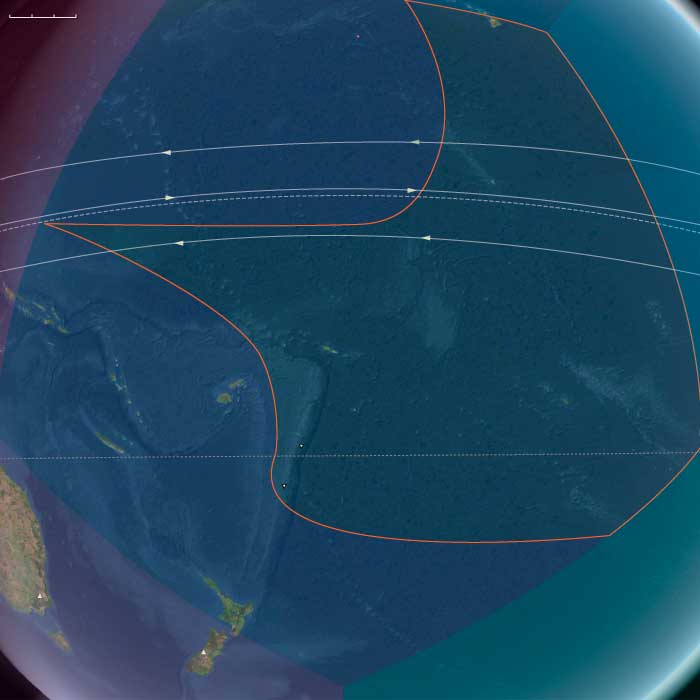

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

The Tonga–Samoa–Fiji triangle served as the political-economic core of the Tuʻi Tonga network.

-

Taputapuātea marae integrated the Societies, Cooks, Marquesas, and Tuamotus into a ritual federation.

-

Marquesas–Societies voyages reinforced alliances and exchange.

-

Hawaiʻi remained marginal but increasingly tied into Polynesian exchange spheres through exploratory voyages.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Divine kingship (Tuʻi Tonga) emphasized sacred descent and cosmological order; langi tombs materialized chiefly power.

-

Taputapuātea marae became the religious axis of Polynesia, symbolizing shared gods, genealogies, and rituals.

-

Samoa’s fine mats functioned as sacred wealth in ritual exchanges, embodying ancestral mana.

-

Marquesan meʻae ritual sites anchored clan cosmologies.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Diversified subsistence strategies (taro, yams, breadfruit, reef fish, arboriculture) reduced vulnerability to storms.

-

Redistributive rituals (potlatch-like feasting, fine mat exchanges, temple ceremonies) stabilized inequalities and alliances.

-

Voyaging networks linked atolls to high-island surpluses, preventing famine.

-

Cultural integration through marae cults and Tongan overlordship strengthened resilience against localized ecological disasters.

Long-Term Significance

By 1107 CE, West Polynesia stood as the political and religious center of Polynesia:

-

The Tuʻi Tonga dynasty extended real political influence across the western Pacific.

-

The Taputapuātea marae created a shared cultic network that gave ideological cohesion to the far-flung Polynesian world.

-

Samoan councils preserved balance and cultural prestige through oratory, kinship, and fine mats.

-

Together, these systems integrated West Polynesia into a maritime commonwealth that influenced all of Polynesia, anchoring later exploration and state formation in Hawaiʻi, Aotearoa, and Rapa Nui.

Groups

- Hawaiʻi

- Fiji

- Samoan, or Navigators Islands

- Tahitians

- Ellice Islands/Tuvalu

- Cook Islanders

- Hawaiians, Native

- Marquesas Islands

- Society Islands

- Tokelau

- Tonga, Kingdom of