West Polynesia (1828–1971 CE): Chiefly States, Colonial …

Years: 1828 - 1971

West Polynesia (1828–1971 CE): Chiefly States, Colonial Rule, and the Making of Modern Island Nations

Geography & Environmental Context

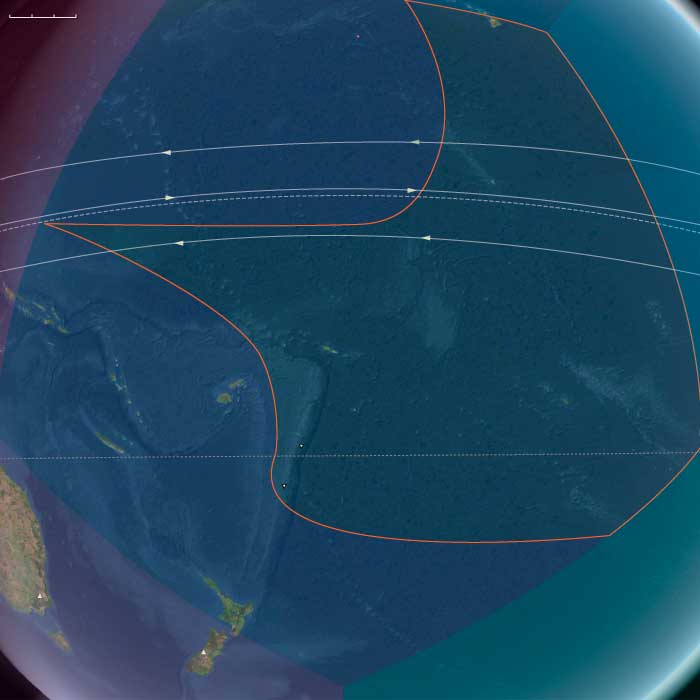

West Polynesia comprises the Big Island of Hawai‘i, Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu, Tokelau, the Cook Islands, and French Polynesia (Tahiti, Society Islands, Tuamotus, Marquesas). Anchors include the volcanic high islands of Hawai‘i, Savai‘i, Upolu, and Tahiti, the atoll chains of Tuvalu and Tokelau, and the reef-fringed lagoons of the Cooks and Society Islands. Tropical climates with trade winds, cyclones, and El Niño variability shaped agriculture and fisheries.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Cyclones periodically devastated atolls, ruining breadfruit and coconut crops; volcanic activity in Hawai‘i continued to add land and hazards. Drought pulses alternated with heavy rains. After WWII, population growth, urbanization, and tourism increased stress on reefs, water, and soils.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Agriculture & fishing: Taro terraces, breadfruit groves, bananas, and coconuts anchored diets; reef fishing and pelagic catches provided protein.

-

Colonial economies: Missionization, copra, cotton (briefly during the U.S. Civil War), and later phosphate (in nearby Banaba) reoriented production.

-

Urbanization: Honolulu grew into a Pacific hub; Apia and Nuku‘alofa consolidated as capitals; Pape‘ete became an administrative and tourism center. Rural–urban migration accelerated after 1950.

-

Land tenure: Customary land systems persisted in Samoa and Tonga, while French and British colonial laws altered tenure in Tahiti and the Cooks.

Technology & Material Culture

-

19th century: Sailing canoes gave way to schooners and steamers; missions introduced literacy, printing presses, and churches.

-

20th century: Radios, outboard motors, concrete housing, and airstrips changed daily life. Hawai‘i industrialized sugar and pineapple; Tahiti saw early tourism.

-

Everyday culture: Tapa cloth, mats, and canoe carving endured; hymnals, guitars, and radios hybridized musical traditions.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Migration: Contract labor flowed to plantations in Hawai‘i and Fiji; later, migration to New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. expanded.

-

Shipping & air routes: Honolulu linked Asia and the Americas; inter-island schooners and postwar airlines connected archipelagos.

-

War corridors: WWII militarized Hawai‘i, Samoa, and Tahiti; bases and troop movements transformed economies and gender roles.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Religion: Christianity became dominant; denominations mapped onto village life.

-

Chiefly systems: Tonga retained monarchy; Samoa balanced matai (chiefly) titles with colonial administrations; Hawai‘i’s monarchy was overthrown (1893), annexed by the U.S. (1898).

-

Nationalism & culture: Samoan Mau movement (1920s–30s) pressed for self-rule; hula and Hawaiian language revival gained momentum mid-20th century; Tahitian and Cook Islands dance and song flourished; sport (rugby) became a regional identity marker.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Food security: Breadfruit fermentation pits, taro terraces, and reef tenure buffered storms and droughts.

-

Customary stewardship: Ra‘ui and kapu–style closures protected fisheries and sacred sites; adaptation persisted under colonial pressure.

-

Postwar economies: Remittances and military spending stabilized small islands; atolls coped with freshwater scarcity via cisterns.

Political & Military Shocks

-

Colonization: Britain, France, Germany, and the U.S. divided the region—Hawai‘i annexed (1898), American and German Samoa partitioned (1899), French protectorate over Tahiti (1842).

-

WWII: Hawai‘i placed under martial law; Samoa and Tahiti supplied bases; Pacific war reshaped geopolitics.

-

Decolonization: Western Samoa achieved independence (1962); Cook Islands (1965) and later Niue entered free association with New Zealand; French Polynesia remained French (later nuclear testing site, post-1960s). Tonga stayed independent but under treaties.

Transition

Between 1828 and 1971, West Polynesia traveled from missionary kingdoms and colonial rule to self-governing island nations and diaspora networks. Sugar and pineapple reshaped Hawai‘i; Samoa’s Mau movement pioneered Polynesian nonviolent nationalism; Tonga navigated independence through treaties; French Polynesia moved toward greater autonomy under French control. By 1971, Polynesian societies combined church, chiefs, and modern states, sustained by remittances, customary land, and a growing Pacific identity—poised for late-20th-century debates over nuclear testing, tourism, and sovereignty.

Groups

- Hawaiʻi

- Fiji

- Polynesians

- Samoan, or Navigators Islands

- Tahitians

- Ellice Islands/Tuvalu

- Cook Islanders

- Hawaiians, Native

- Marquesas Islands

- Tokelau

- Tonga, Kingdom of

Topics

Commodoties

- Rocks, sand, and gravel

- Fish and game

- Hides and feathers

- Grains and produce

- Fibers

- Ceramics

- Salt

- Lumber