West Polynesia (1540–1683 CE): Voyaging Chiefdoms, marae …

Years: 1540 - 1683

West Polynesia (1540–1683 CE): Voyaging Chiefdoms, marae Ritual Centers, and Agricultural Intensification

Geography & Environmental Context

West Polynesia includes the Big Island of Hawai‘i, the archipelagos of Tonga and Samoa, Tuvalu, Tokelau, the Cook Islands, and French Polynesia (Tahiti, the Society Islands, the Marquesas, the Tuamotus, and others). This subregion combines volcanic high islands like Hawai‘i, Tahiti, and Savai‘i, coral atolls such as Tuvalu and Tokelau, and rugged chains like the Marquesas. Anchors include the Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa volcanoes on Hawai‘i, the ʻUpolu ridges of Samoa, the coral lagoons of the Tuamotus, and the fertile valleys of Tahiti. These diverse environments provided both abundance and constraints, shaping lifeways across the island groups.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The climate was generally tropical with marked wet and dry seasons, though variation was pronounced. High islands captured heavy rainfall, feeding rivers and fertile soils for irrigated taro terraces, while leeward coasts and atolls were more drought-prone. The Little Ice Age brought slightly cooler conditions and episodic droughts, stressing marginal atolls like Tuvalu and Tokelau. Cyclones periodically damaged coastal settlements and plantations. Yet the richness of lagoons, reefs, and deep-sea fisheries, especially around Tahiti and Samoa, provided resilient marine resources even during climatic fluctuations.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Hawai‘i (Big Island): Vast agricultural field systems expanded across the slopes of Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea, producing taro in irrigated valleys and sweet potatoes in extensive dryland plots. Fishponds lined the Kona and Hilo coasts, anchoring large chiefly centers.

-

Samoa and Tonga: Communities combined irrigated taro and breadfruit groves with abundant fishing. Settlement patterns featured fortified villages (olo) and chiefly compounds, with ʻUpolu and Tongatapu as political hubs.

-

Tuvalu and Tokelau: On these atolls, coconuts, breadfruit, and pulaka (swamp taro grown in pits) formed staples, with reef and lagoon fishing sustaining smaller, more vulnerable populations.

-

Cook Islands and Tahiti (Society Islands): Fertile valleys supported intensive horticulture, with irrigated taro and yam terraces feeding populous chiefdoms. Tahiti grew into a paramount center of ritual and political power.

-

Marquesas: Steep valleys fostered dense settlement supported by dryland farming of breadfruit and sweet potatoes. Hierarchical chiefdoms emerged, with ceremonial plazas and carved stone platforms anchoring ritual life.

Technology & Material Culture

Canoe technology reached a high level of sophistication: double-hulled voyaging canoes enabled inter-island exchange across long distances, while outrigger canoes served fishing and transport needs. Basalt adzes shaped houses, canoes, and ritual platforms. In Hawai‘i, dryland agricultural field walls and massive fishpond complexes reflected advanced engineering. Across Samoa and Tonga, finely woven mats (ʻie toga) served as prestige goods, exchanged in ceremonies and marking chiefly status. In Tahiti and the Marquesas, tattooing reached elaborate forms, inscribing social identity and cosmological protection. Wooden images of deities, feather regalia, and tapa cloth painted with plant dyes enriched material and symbolic culture.

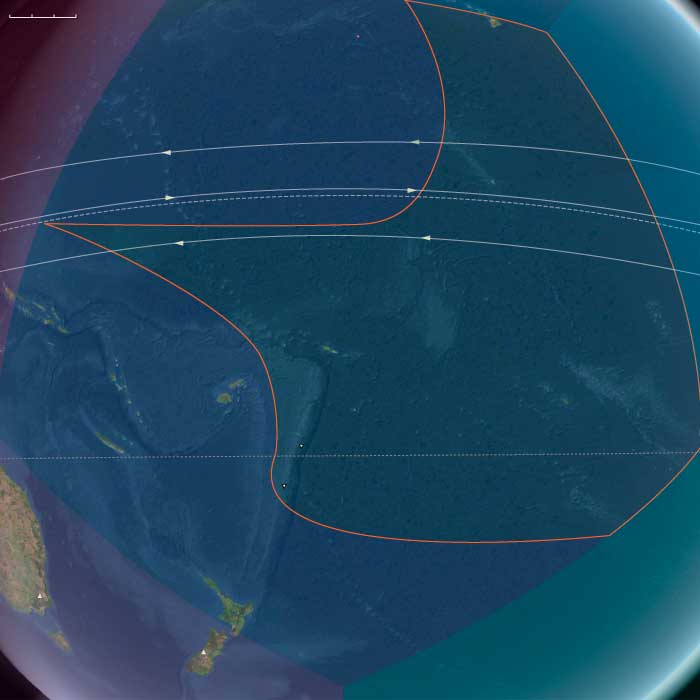

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Inter-island voyaging knit the subregion together:

-

Hawai‘i maintained cohesion among districts through chiefly exchange and warfare, with canoes crossing channels like the treacherous ʻAlenuihāhā between Hawai‘i and Maui.

-

Tonga extended influence outward through tribute and marriage alliances, touching Samoa, ʻUvea, and Fiji.

-

Samoa exchanged prestige goods, mats, and canoe materials widely, remaining central in cultural transmission.

-

Tuvalu and Tokelau sustained smaller-scale circuits linking their atolls with Samoa and Tonga.

-

Tahiti and the Society Islands became hubs of exchange with the Tuamotus, Marquesas, and Cooks, binding East and West Polynesia through ritual and trade.

-

The Marquesas maintained their own voyaging traditions, linking valleys and outer islets in a rugged seascape.

These routes spread goods such as mats, red feathers, basalt adzes, pigs, and ritual knowledge, reinforcing shared cultural patterns across the subregion.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Religion centered on the veneration of gods tied to fertility, war, and navigation. In Hawai‘i, temples (heiau) dedicated to Kū and Lono structured ritual and chiefly legitimacy. In Samoa and Tonga, ʻaitu spirits and lineage gods received offerings in communal rituals, while ceremonial exchanges of mats and kava reinforced chiefly hierarchies. In Tahiti, elaborate marae temple complexes served as stage for festivals honoring gods like ʻOro, with feathered girdles (maro ʻura) signifying paramount status. Tattooing in the Marquesas encoded cosmological narratives onto bodies, while across the subregion, oral traditions and chants preserved genealogies that linked leaders back to divine ancestors.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Island communities balanced resource use through ingenuity:

-

On the Big Island, extensive dryland systems using stone alignments and mulching stabilized crops against drought.

-

Fishponds buffered against fluctuations in marine catch, providing protein reserves.

-

In the atolls of Tuvalu and Tokelau, deep pits were dug into freshwater lenses to cultivate pulaka, a brilliant adaptation to thin soils.

-

In the Society Islands and Marquesas, valley terracing and intercropping of breadfruit, taro, and yams sustained high populations.

-

Social systems of redistribution ensured surplus moved from rich districts to poorer ones through chiefly feasts and tribute, embedding resilience in the political structure.

Transition

Between 1540 and 1683, West Polynesia thrived as a constellation of populous and innovative chiefdoms. Agricultural intensification on Hawai‘i and Tahiti, ritual centralization in Tonga and Samoa, and dense settlement in the Marquesas reflected both ecological adaptation and the consolidation of chiefly power. Networks of exchange and shared symbolic traditions bound the subregion together, even as local rivalries produced shifting balances of authority. European vessels had not yet penetrated these waters, but the systems of agriculture, aquaculture, voyaging, and ritual authority developed in this period created the foundations that would confront the disruptions of global contact in the centuries to follow.

Groups

- Hawaiʻi

- Fiji

- Polynesians

- Samoan, or Navigators Islands

- Tahitians

- Ellice Islands/Tuvalu

- Cook Islanders

- Hawaiians, Native

- Marquesas Islands

- Tokelau

- Tonga, Kingdom of

Topics

Commodoties

- Rocks, sand, and gravel

- Fish and game

- Hides and feathers

- Grains and produce

- Fibers

- Ceramics

- Salt

- Lumber