Antarctica (6,093–4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Retreating …

Years: 6093BCE - 4366BCE

Antarctica (6,093–4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Retreating Ice and Expanding Life at the Edge of the World

Geographic & Environmental Context

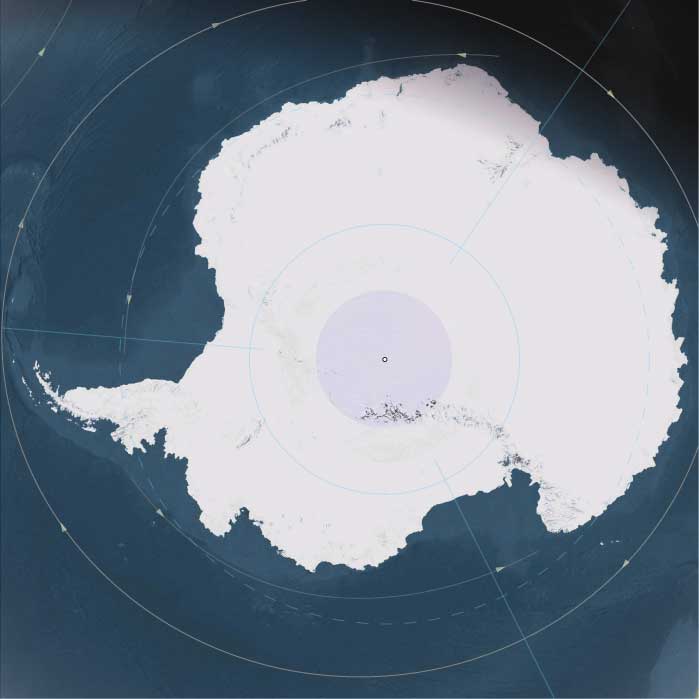

During the Middle Holocene, Antarctica stood at its largest ice extent since the Pleistocene but was steadily retreating toward its modern boundaries.

The East Antarctic Ice Sheet remained massive and stable, capped by the polar plateau, while the West Antarctic Ice Sheet continued its slow recession along the Ross and Amundsen sectors.

Major ice shelves (Ross, Filchner–Ronne, Amery) persisted but had withdrawn slightly from their glacial highstand margins.

Isolated oases and rock outcrops—the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Bunger Oasis, Larsemann Hills, and ice-free ridges of the Antarctic Peninsula—expanded to reveal saline lakes, weathered moraine, and patches of barren tundra.

Surrounding seas—the Ross, Weddell, Bellingshausen, and Amundsen—were alive with seasonal ice, polynyas, and nutrient-rich upwellings that tied Antarctica to the Southern Ocean biosphere.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm interval (roughly 7,000–4,000 BCE) brought temperatures 1–2 °C higher than later millennia.

-

Coastal regions experienced longer ice-free summers and reduced sea-ice extent.

-

Moisture transport from lower latitudes increased, yielding more snow on the coastal fringe and less in the interior.

-

Persistent katabatic winds and the polar high pressure kept the central plateau hyper-arid.

-

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) remained strong, driving productivity in marginal seas and sustaining dense krill populations.

Overall, Antarctica entered a period of relative climatic equilibrium—cold, but biologically vibrant along its edges.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human occupation touched the continent at this time.

Instead, its shorelines and oases were colonized by life returning after glacial retreat:

-

Coastal tundras harbored mosses, liverworts, lichens, and microbial mats around melt-water streams and saline lakes.

-

Seabirds (petrels, skuas) nested on ice-free headlands; Adélie and gentoo penguins established small colonies along peninsula beaches.

-

Seals (fur, elephant, leopard, Weddell) hauled out on newly exposed coasts.

-

Offshore, krill blooms and phytoplankton carpets fed whales, fish, and squid.

The continent’s biosphere remained concentrated within a narrow coastal margin where sea and ice met.

Technology & Material Culture

Human technological horizons elsewhere had advanced to pottery and early metallurgy, but Antarctica lay far beyond navigation and survival limits.

No boats, clothing, or fuel systems of the period could sustain occupation in its polar environment.

All evidence of activity remains geophysical and biological, not archaeological.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Ecological flows replaced human traffic.

-

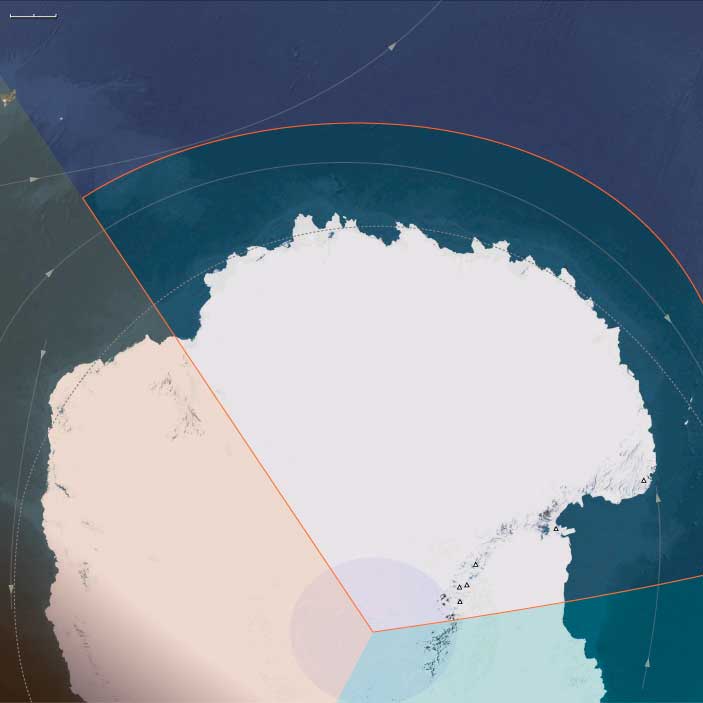

The ACC linked Antarctic waters to the South Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans, circulating nutrients and organisms.

-

Seasonal sea-ice advance and retreat regulated migration cycles for whales, seals, and birds.

-

Polynyas (open-water windows within ice fields) served as oases of productivity, feeding ground for penguins and marine mammals.

-

Airborne transport of dust and pollen from southern continents subtly altered Antarctica’s chemical and biological makeup.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human culture yet existed to assign meaning to this land. Its symbolism was entirely natural—the recurrence of seasons, the calving of icebergs, and the cyclic arrival of migrants defined time and memory for the biosphere.

In the absence of human observers, Antarctica embodied pure process: the planet’s own ritual of freeze and renewal.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience was structural and biological:

-

Krill and plankton adjusted to changing ice algae cycles, ensuring continuity through cold fluctuations.

-

Microbial and plant colonies regenerated rapidly after freeze–thaw disturbances.

-

Seabird and seal populations shifted colonies with ice margin movements.

-

Glacial and volcanic feedbacks cycled nutrients through soil and sea, maintaining a delicate but productive equilibrium.

Long-Term Significance

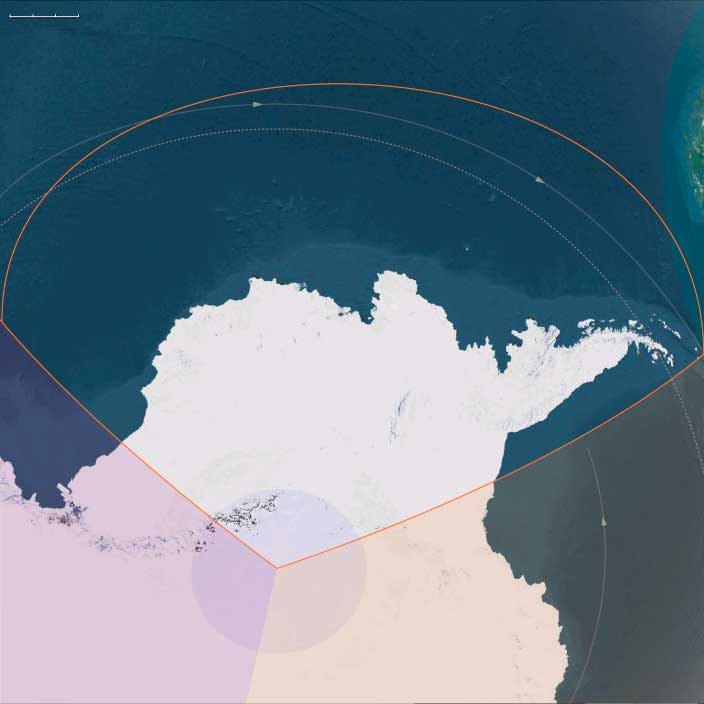

By 4,366 BCE, Antarctica had entered a mature Holocene state: glaciers largely stable within modern margins, ice-free oases expanding slowly, and coastal ecosystems fully established.

Although no human had yet seen it, Antarctica already functioned as the planet’s climatic and biological keystone—regulating global ocean circulation and anchoring the world’s southern food chains.

It was, and remains, Earth’s most elemental continent: a mirror of climate balance, a repository of ice and light, and a stage awaiting future voyagers.