South Asia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

South Asia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Loess Terraces, Rock Shelters, and Monsoon Pathways

Geographic & Environmental Context

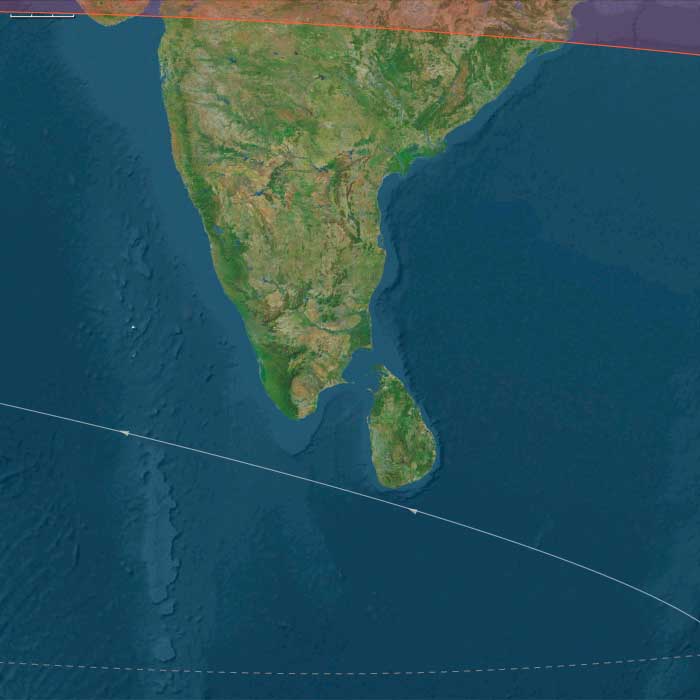

During the late Pleistocene, South Asia was shaped by the contrasts of a weakened monsoon, extensive river terraces, and broad, exposed coastal plains.

The subcontinent spanned two dynamic realms:

-

Upper South Asia: From the Hindu Kush–Karakoram–Himalaya and Indus–Ganga–Brahmaputra basins to the Siwalik and Terai foothills. Here, braided rivers sculpted loess-covered terraces, and glaciers capped the higher Himalaya.

-

Maritime South Asia: The Deccan Peninsula and Sri Lanka—a world of rock shelters, tropical forests, and widened shelf coasts, joined intermittently by land bridges across the Palk Strait.

Together these landscapes supported highly mobile foragers who tracked monsoon pulses between upland caves, plains rivers, and coastal lagoons.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The epoch unfolded under glacial–interglacial oscillations that reshaped both monsoon and river regimes:

-

Cool, dry glacial intervals weakened the Indian summer monsoon; winter westerlies dominated northwest India and the Himalayan forelands.

-

Interstadials briefly restored humidity, recharging lakes and river discharge across the Ganga–Yamuna and Brahmaputra systems.

-

Expanding glaciers in the Karakoram and Greater Himalaya coincided with broad Indus and Ganga terracesbuilt under fluctuating discharge.

-

Peninsular India and Sri Lanka saw contraction of rainforests and expansion of deciduous woodland and savanna under reduced precipitation.

Subsistence & Settlement

Upper South Asia

-

Settlement Patterns:

Seasonal mobility between mountain caves (Swat, Kashmir), Siwalik rock shelters, and riverine terraces along the Indus and Ganga plains. -

Diet and Hunting:

Herd-following economies targeting wild equids, aurochs, nilgai, blackbuck, ibex, markhor, and red deer. River and oxbow habitats supplied fish and waterfowl during interstadials. -

Habitation Evidence:

Caves and open-air hearths in Gandhara, the Rohri chert zone, and the Ganga–Yamuna Doab show continuity from Middle to Upper Paleolithic phases.

Maritime South Asia

-

Rock-Shelter Foragers:

Occupations at Kurnool, Jurreru, and other Deccan sites, where microlithic toolkits indicate long continuity of human presence. -

Coastal Economies:

As sea level fell, broad shelf plains opened along the Konkan–Malabar–Coromandel coasts; foragers gathered shellfish, fish, crabs, and turtles on tidal flats. -

Sri Lanka’s Balangoda Culture:

Hunter–gatherers at Fa-Hien Lena and Batadomba-lenā exploited rainforest mammals (monkeys, porcupine), freshwater fish, and yams, marking one of the world’s earliest successful tropical rainforest adaptations.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Stone Industries:

Blade–flake and geometric microlithic traditions in both northern and southern India mark the full establishment of an Upper Paleolithic trajectory. Rohri chert quarries (Sindh) became major lithic source zones. -

Organic Technologies:

Bone points, eyed needles, and hafted scrapers reflect tailored clothing and woodworking. Digging sticks and hammerstones aided tuber extraction and nut cracking. -

Symbolism and Ornament:

Ochre for body paint or adhesive; perforated beads and pendants appear in late-phase contexts. -

Fire and Cooking:

Structured hearths and roasting pits in caves and dunes suggest deliberate heat control for cooking and toolmaking.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Northwest Passes: Khyber, Kurram, and Bolan gateways linked the Indus basin with Iranian and Central Asian plateaus.

-

River Pathways: Indus, Ganga–Yamuna, and Brahmaputra terraces served as highways for seasonal migration and exchange.

-

Foothill Routes: Siwalik and Terai corridors connected Himalayan uplands to fertile plains.

-

Peninsular Arteries: Godavari–Krishna–Tungabhadra valleys, Palghat and Palakkad gaps across the Western Ghats, and the Palk Strait (often a dry bridge) tied peninsular India to Sri Lanka and beyond.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Ritual & Art:

Hearth renewals, engraved bones, and faunal motifs from northern caves reflect animistic and ritual awareness. Early rock art in southern India (and ochred burials) suggests regional symbolism. -

Social Structure:

Kin-based bands with cooperative foraging and shared tool production; roles in leadership and knowledge (e.g., hunting, healing, or navigation) were situational and seasonal.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Mobility as Strategy: Alternation between upland shelters in cool dry months and river–delta plains during warmer seasons buffered against climatic unpredictability.

-

Ecological Breadth: Combination of hunting, fishing, and plant foraging provided resilience through monsoon weakening.

-

Technological Flexibility: Microblade composites and hafted multipurpose tools allowed rapid adaptation to varied ecologies—from the Thar scrub to the Deccan forests.

-

Maritime Awareness: Knowledge of tidal rhythms and coastal resource scheduling foreshadowed the later Holocene seafaring and shell-working traditions of peninsular India and Sri Lanka.

Transition Toward the Last Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, South Asia’s foragers had diversified into distinct but interconnected ecocultural systems:

-

In the north, cold-adapted upland–river foragers navigated the loess plains beneath glaciated peaks.

-

In the south, microlithic cave dwellers and coastal collectors exploited tropical forests and widening shelves.

Both traditions thrived through technological ingenuity, mobility, and deep ecological knowledge—foundations that would carry them through the Last Glacial Maximum and into the Holocene’s emerging monsoon world.