South Asia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

South Asia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Monsoon Revival, River Lifeways, and Coastal Horizons

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, South Asia evolved from a continent of glacial desiccation to one of rivers, wetlands, and rich coastal ecosystems.

At the Last Glacial Maximum (26,500–19,000 BCE), the Himalayan cryosphere reached its widest extent, depressing regional monsoons and transforming much of northern India into cool steppe and dry savanna. As deglaciation progressed, rivers reawakened, deltas prograded, and the subcontinent’s modern hydrographic architecture—Indus, Ganga, and Brahmaputra—took recognizable form.

Two interconnected ecological spheres emerged:

-

Upper South Asia, encompassing the Hindu Kush–Indus–Ganga–Brahmaputra corridor, where monsoon recovery and floodplain formation drew foragers to riverine habitats.

-

Maritime South Asia, covering Peninsular India, Sri Lanka, and the Indian Ocean islands, where rising seas created estuaries, lagoons, and archipelagos, transforming coastlines into lifelines.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The transition from glacial to Holocene climates was expressed through distinct monsoonal rhythms:

-

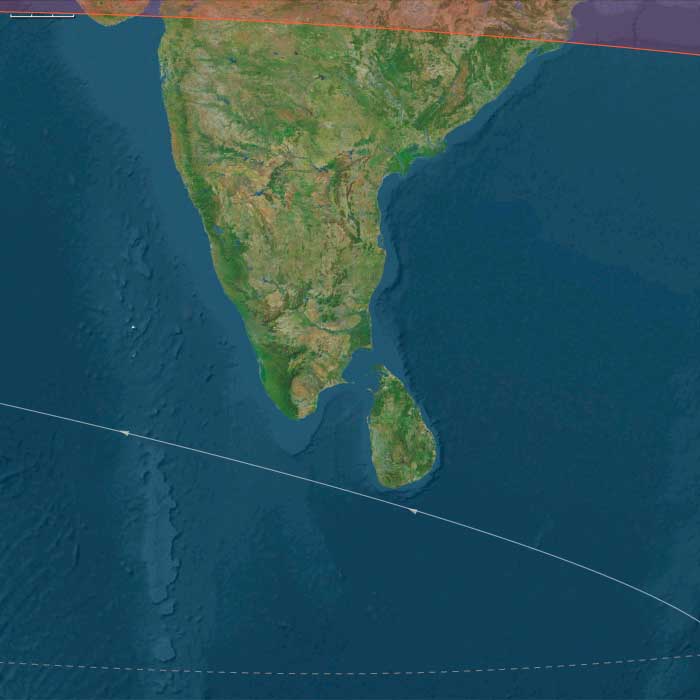

Last Glacial Maximum: Cold, dry; weak southwest monsoon; widespread grasslands in northern India; Sri Lanka connected to the mainland by the Palk Isthmus.

-

Bølling–Allerød (14,700–12,900 BCE): Rapid warming strengthened monsoons, expanding forests and wetlands; rainfall rejuvenated Indus and Ganga catchments.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 BCE): Short cooling reversed humid gains; savannas expanded; floodplains shrank; seasonal mobility intensified.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): Monsoon stabilized at near-modern strength; deltaic and estuarine systems matured; Sri Lanka was isolated by sea-level rise, and the Deccan coasts took their present form.

The interplay of glacial retreat and monsoon renewal created a mosaic of forests, grasslands, and wetlands, inviting new settlement strategies.

Subsistence & Settlement

South Asian foragers adopted increasingly river-anchored and coastal-integrated lifeways, balancing mobility and sedentarism:

-

Upper South Asia:

In the Punjab Doabs, Siwalik foothills, and Middle Ganga plains, groups focused on riverine ecologies—fishing, trapping turtles, hunting marsh deer, and gathering nuts and reeds.

At sites such as Sanghao Cave (northwest Pakistan) and foothill springs in the Siwaliks and Kashmir, repeated occupations suggest semi-sedentary foraging linked to predictable monsoon resources.

Broad-spectrum diets evolved: fish and shellfish joined deer, boar, and bovid hunting, while gathered fruits, nuts, and seeds supplemented protein. -

Maritime South Asia:

Along the Konkan, Malabar, and Coromandel coasts, shell middens mark growing dependence on marine resources—fish, mollusks, turtles, and seabirds.

Inland groups in the Deccan river basins hunted antelope and boar, gathered wild yams and nut mast, and reoccupied caves and shelters seasonally.

In Sri Lanka, the long microlithic sequence of sites such as Fa Hien and Batadomba-lena shows persistent rainforest foraging, with deer, monkeys, and fruit forming the dietary core.

Settlements followed river confluences, lagoons, and monsoon-fed springs, producing a landscape of enduring camps that presaged later village permanence.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological continuity and adaptation reflected a balance of ancient traditions and new environmental challenges:

-

Microlithic industries (triangles, trapezes, lunates) proliferated from the Thar to Sri Lanka, providing lightweight, versatile hunting tools.

-

Grinding stones appeared for processing wild grains and nuts.

-

Bone harpoons and fish gorges, along with net weights and fiber cordage, signaled intensive riverine fishing.

-

Early dugout canoe precursors likely aided Palk Strait crossings and coastal travel.

-

Ochre, shell beads, and geometric engravings reveal enduring symbolic practices in both caves and open sites.

These innovations signaled a society in technological equilibrium—mobile yet inventive, grounded in tradition but adaptive to changing coasts and climates.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

South Asia’s geography fostered movement along both hydrological and maritime axes:

-

Indus and Ganga–Yamuna river systems linked the Himalayan piedmont with lowland plains, serving as arteries of migration and exchange.

-

Palaeochannels such as the Ghaggar–Hakra acted as wet-season corridors.

-

Deccan rivers (Godavari, Krishna, Kaveri, Tungabhadra) joined interior and coastal ecologies.

-

Ghats passes allowed trans-peninsular mobility between the western and eastern coasts.

-

In the south, Palk Strait crossings persisted until sea-level rise demanded raft or canoe passage, maintaining ties between the Tamil–Andhra coast and Sri Lanka.

These routes enabled not only resource exchange but also the diffusion of ideas, materials, and seasonal alliances—the first web of South Asia’s interconnected cultural geography.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Cultural expression remained rich and regionally distinctive:

-

Ochre burials and riverbank offerings along Indus–Ganga corridors suggest ritual engagement with water as a living entity.

-

Cave art and bead assemblages across peninsular India and Sri Lanka reflect continuity of symbolic behavior spanning tens of millennia.

-

Feasting middens and shell deposits indicate communal rituals centered on shared consumption and renewal.

-

Seasonal rituals tied to first-fish and large game echoed early cosmologies of abundance and cyclical renewal.

These symbolic systems intertwined ecological rhythms with social memory, anchoring communities to the monsoon’s pulse.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience in Late Pleistocene–Holocene South Asia derived from ecological intelligence and mobility:

-

Dietary breadth and food preservation (smoked fish, dried meat, nut pastes) mitigated climatic volatility during the Younger Dryas.

-

Mobility tracking monsoon fronts ensured access to water and seasonal foods.

-

Dual foraging strategies—riverine and coastal—buffered inland drought and forest contraction.

-

Emergent plant management, including proto-horticultural care of tubers and grain grasses, reflected early adaptation toward food security.

These patterns demonstrate how monsoon variability acted not as constraint but as teacher, cultivating resilience through flexibility.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, South Asia had achieved an environmental and cultural synthesis that bridged glacial foraging and Holocene settlement:

-

Upper South Asia was fully reforested and hydrologically stable, hosting broad-spectrum riverine economies.

-

Maritime South Asia had turned coasts and estuaries into centers of abundance and exchange.

-

Sri Lanka’s rainforest foragers maintained cultural continuity stretching back over 40,000 years.

Together, these traditions set the stage for the Neolithic transitions of Mehrgarh and the Ganga Plain, the maritime horizons of the Arabian Sea, and the enduring dialogue between river, monsoon, and coast that would define South Asia’s Holocene civilizations.