South Asia (1108 – 1251 CE): Sultanate …

Years: 1108 - 1251

South Asia (1108 – 1251 CE): Sultanate Frontiers and Maritime Kingdoms

Between 1108 and 1251 CE, South Asia stood at a civilizational crossroads. In the north, Turkic cavalry from the Ghurid highlands swept through the Punjab and the Ganga plains, founding the Delhi Sultanate and transforming Indo-Islamic governance. In the south, Tamil, Kannada, and Sinhalese monarchies perfected irrigation and temple economies while competing for maritime supremacy across the Indian Ocean. Along the coasts and islands, Islam took root through trade, uniting the subcontinent with Arabia and East Africa. This age, poised between the Cholas’ twilight and the Sultanate’s dawn, bound the land and sea of South Asia into a single, intricate web of conquest, piety, and exchange.

Geographic and Environmental Context

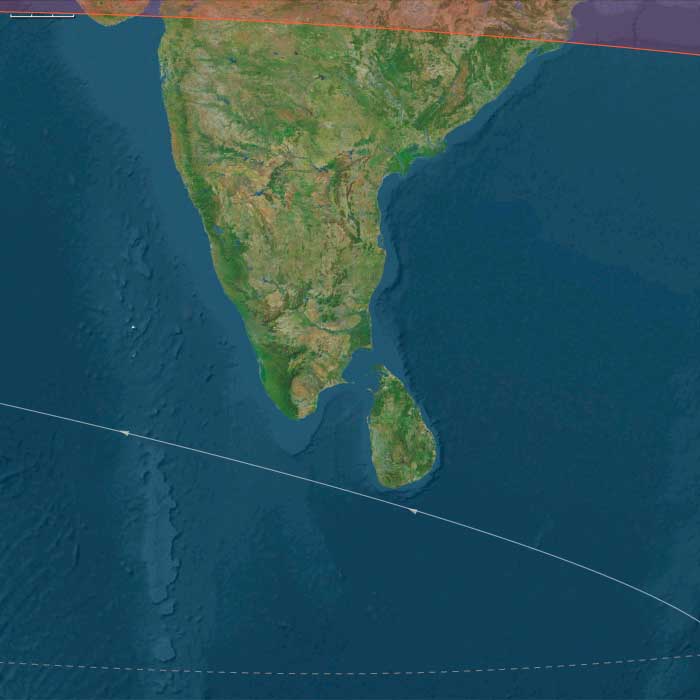

South Asia in this age stretched from the Hindu Kush and Himalayan passes to the Dravidian peninsula and Indian Ocean archipelagos.

-

In Upper South Asia, the Kabul–Gandhara gateways, Punjab–Doab plains, and Ganga–Brahmaputra delta formed the agrarian and military heartlands of empire.

-

The Kathmandu Valley, Bhutan’s high valleys, and Arakan–Chindwin corridor bridged the Himalayas and Southeast Asia.

-

In Maritime South Asia, the Tamil plains, Deccan plateau, Kerala backwaters, and Sri Lankan river basins nurtured dense settlements, while the Maldives and Lakshadweep linked the subcontinent to the wider Indian Ocean.

From the monsoon-fed rice fields of Bengal to the pearl banks of Ceylon, every ecological niche contributed to the subcontinent’s layered prosperity.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The late Medieval Warm Period brought generally stable monsoon rainfall and mild temperatures, though the first signs of variability appeared.

-

North India and the Punjab–Doab experienced alternating floods and droughts, prompting new irrigation systems.

-

Bengal’s delta expanded, sustaining rice surpluses and maritime ports.

-

Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu enjoyed fertile monsoon cycles, while Deccan interiors faced periodic dryness mitigated by tank irrigation.

-

Across the Himalayan valleys, warmer conditions kept salt–grain exchange routes open.

This climatic balance underwrote both agrarian intensification and long-distance trade across land and sea.

Societies and Political Developments

The Northern Sultanate Frontier:

The late 12th century witnessed the Ghurid conquest of northern India. From Afghanistan, Mu‘izz al-Din Muhammad of Ghur and his generals seized Lahore and Delhi, establishing Turkic rule. In 1206, Qutb al-Din Aibak founded the Delhi Sultanate, succeeded by Iltutmish (r. 1211–1236), who consolidated authority and gained recognition from the Abbasid Caliph.

Under Razia Sultan (r. 1236–1240), Delhi briefly saw a woman on the throne—an exceptional episode in Islamic history.

Mongol incursions under Chinggis Khan’s successors pressured the northwest, but the Sultanate endured, balancing Persianate administration with Indian agrarian foundations.

Bengal fell to Bakhtiyar Khalji (c. 1204) and became a semi-autonomous frontier province under Delhi’s loose suzerainty. Its riverine ports—Lakhnauti and Sonargaon—linked inland rice surpluses to maritime export.

Kashmir and Rajasthan remained centers of Hindu polity and Sanskrit scholarship, while Kashmiri temples retained influence until the mid-13th century.

The Himalayan Realms:

In Nepal, the Malla dynasty unified the Kathmandu Valley after 1200, building the pagoda temples of Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur.

Bhutan saw the spread of Drukpa Kagyu Buddhism from Tibet, anchoring monastic estates in fertile valleys.

Arakan (Rakhine) and the Chindwin valley developed as rice- and elephant-producing zones, linking Bengal and Pagan Burma.

Southern and Maritime Kingdoms:

In the Tamil South, the Chola Empire, dominant since the 10th century, waned under Kulottunga I and his successors, while the Pandyas resurged from Madurai, contesting Chola supremacy.

The Hoysalas of Karnataka patronized the Hoysaleswara and Chennakesava temples, exemplifying Dravidian architecture.

In Sri Lanka, the Polonnaruwa kingdom under Parakramabahu I (r. 1153–1186) reached its zenith, uniting the island and extending irrigation across the dry zone.

The Maldives, converted to Islam in 1153, became a sultanate integrated into Arabian and Indian trade routes.

The Lakshadweep islands served as spice entrepôts, while the Chagos Archipelago remained sparsely used but strategically placed along sailing lanes.

Economy and Trade

Agriculture:

-

Northern plains: wheat, barley, pulses.

-

Bengal: rice, sugarcane, and jute.

-

Deccan and Tamil regions: rice, pepper, millets, and coconuts.

-

Himalayan uplands: barley, buckwheat, and wool.

-

Sri Lanka: irrigated rice and spices.

Trade:

-

Overland routes via Khyber and Bolan passes carried horses, slaves, and textiles between Central Asia and Delhi.

-

Bengal’s river systems moved rice and cotton to Bay of Bengal ports.

-

Indian Ocean trade connected Calicut, Quilon, Nagapattinam, and Sri Lankan ports to Aden, Hormuz, and Canton.

-

Pepper, pearls, elephants, and cowries circulated widely, while Arabian horses and Persian silver entered the subcontinent in return.

Coinage and finance:

The Delhi Sultanate’s silver tanka and copper jital standardized currency, while Maldives cowries served as universal small change across Africa and Asia.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Irrigation expanded dramatically: Sultanate canals in the Doab, Polonnaruwa’s reservoirs in Sri Lanka, and South Indian tanks in the Deccan.

-

Military innovation: Turkish cavalry and composite bows redefined warfare; hill fortresses guarded regional polities.

-

Architecture: Delhi’s Qutb Minar and Quwwat al-Islam Mosque, Sri Lanka’s Gal Vihara, and Hoysala temples in Karnataka epitomized religious artistry.

-

Maritime technology: Tamil and Kerala shipwrights constructed sturdy dhows and sewn-plank vessels for monsoon voyages.

-

Crafts and textiles: Bengal muslins, Gujarati cottons, and Tamil bronzes were prized throughout the Indian Ocean.

Belief and Symbolism

Religion in this era mirrored South Asia’s diversity and convergence:

-

Islam: The Sultanate established mosques, madrasas, and Sufi hospices (notably the Chishti order in Delhi under Nizamuddin Auliya).

-

Hinduism: Temple culture flourished across the south and highlands, sustaining Shaiva and Vaishnava devotion.

-

Buddhism: Declined in northern India but persisted vibrantly in Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bhutan, where Vajrayana and Theravāda lineages coexisted.

-

Syncretism: Along the coasts and deltas, merchant communities blended Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic practices, creating a shared maritime cosmopolitanism.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

The Khyber–Bolan gateways: conduits for conquests and trade between Central Asia and Delhi.

-

The Grand Trunk precursor: Lahore ⇄ Delhi ⇄ Bihar ⇄ Bengal, connecting military and market towns.

-

Bay of Bengal routes: Sonargaon ⇄ Nagapattinam ⇄ Sri Lanka ⇄ Maldives ⇄ Aden.

-

Himalayan passes: Salt and wool caravans between Nepal–Tibet and Bhutan–Assam.

-

Malabar coast lanes: pepper, textiles, and cowries moved through Calicut to the Red Sea.

These overland and maritime arteries bound South Asia to every major civilization of the age.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Delhi’s resilience lay in transforming conquest into administration—balancing Turkic elites, Persian culture, and Indian agrarian systems.

-

Bengal’s adaptability came from deltaic agriculture and maritime autonomy.

-

Southern polities survived drought and warfare through irrigation and temple-centered redistribution.

-

Island sultanates and coastal ports adjusted seamlessly to global trade shifts.

-

Across the Himalayas, monastic estates and village cooperatives managed environmental risk through collective ritual and resource sharing.

These adaptive systems sustained continuity despite invasions, climate stress, and political fragmentation.

Long-Term Significance

By 1251 CE, South Asia had entered a new political and commercial configuration:

-

The Delhi Sultanate was entrenched from the Punjab to Bengal, heralding the long era of Indo-Islamic synthesis.

-

The Himalayan realms of Nepal, Bhutan, and Arakan bridged Central and Southeast Asia through Buddhism and trade.

-

The southern kingdoms—Cholas, Pandyas, and Hoysalas—dominated peninsular culture and architecture.

-

Sri Lanka’s Polonnaruwa, though soon to wane, stood as the zenith of hydraulic civilization.

-

The Maldives and Malabar linked India to the western oceanic world, their cowries and spices circulating across empires.

This High Medieval South Asia—maritime and continental, sacred and mercantile—defined the political and cultural foundations of the Indian Ocean’s future centuries.

People

Groups

- Tajik people

- Kirat people

- Iranian peoples

- Hinduism

- Pashtun people (Pushtuns, Pakhtuns, or Pathans)

- Jainism

- Buddhism

- Buddhism, Tibetan

- Khas peoples

- India, Classical

- Buddhism, Mahayana

- Tokharistan (Kushan Bactria)

- Gandhāra

- Bon

- Bumthang, Kingdom of

- Islam

- Palas of Bengal, Empire of the

- Abbasid Caliphate (Baghdad)

- Paramara dynasty

- Rakhine State (Arakanese Kingdom)

- Chandelas (Candellas) of Khajuraho, Kingdom of the

- Abbasid Caliphate (Baghdad)

- Cauhans (Chamnas) of Ajmer and Delhi, Rajput Kingdom of the

- Ghilzai (Pashtun tribal confederacy)

- Gujarat, Solanki Kingdom of

- Rakhine (Arakanese) people

- Ghurid dynasty

- Senas of Bengal, Kingdom of the

- Gahadvalas

- Ghurid Sultanate

- Delhi, Sultanate of (Ghurid Dynasty)

- Malla (Nepal)

- Delhi, Sultanate of (Mamluk or Ghulam Dynasty)

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

- Commerce

- Writing

- Architecture

- Sculpture

- Conflict

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Metallurgy

- Medicine

- Mathematics

- Astronomy

- Philosophy and logic