Upper East Asia (1108 – 1251 CE): …

Years: 1108 - 1251

Upper East Asia (1108 – 1251 CE): Mongol Unification, Tibetan Buddhism, and Frontier States

Geographic and Environmental Context

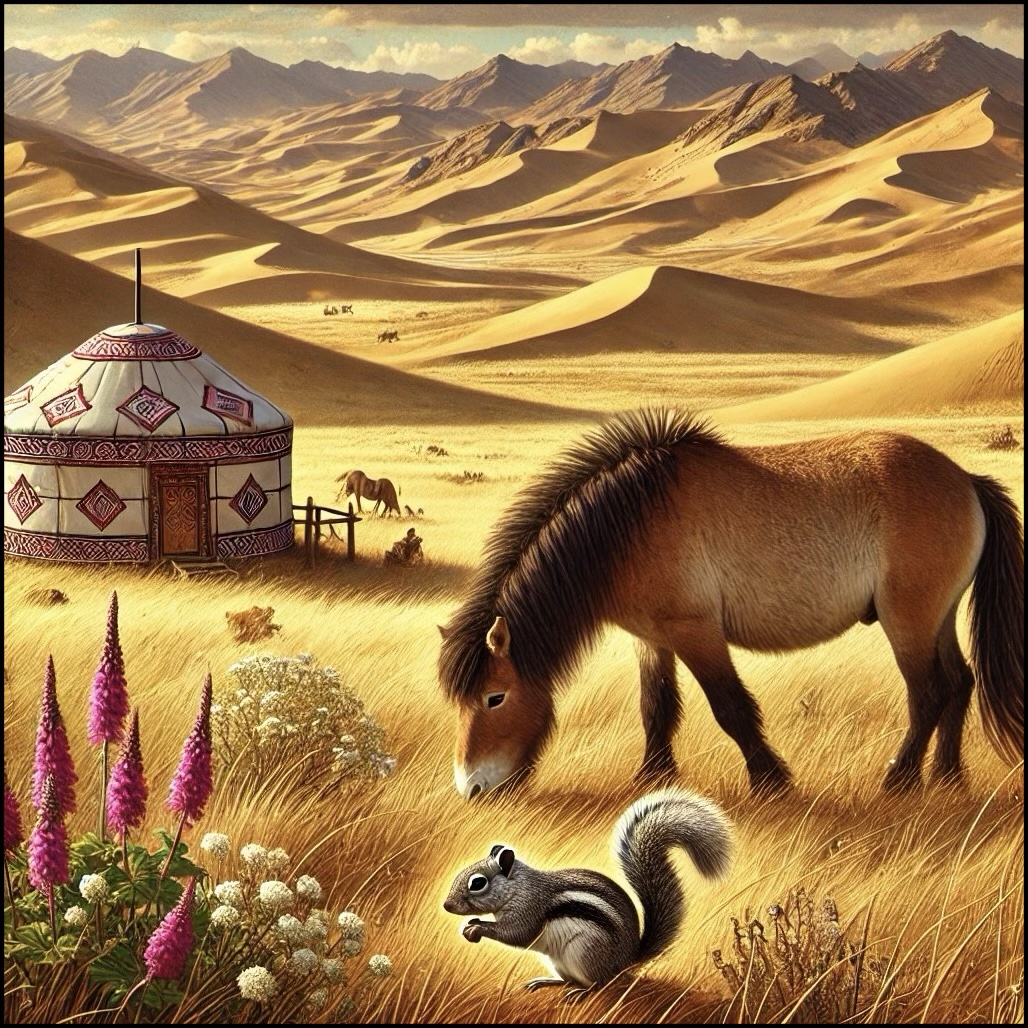

Upper East Asia includes Mongolia and western China, including Tibet, Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and western Heilongjiang.

-

The Mongolian steppe supported mobile pastoralism and horse-based societies.

-

The Tibetan Plateau featured high-altitude valleys and monasteries, sustaining agro-pastoral lifeways.

-

Xinjiang and the Tarim Basin held oasis towns along the Silk Road, linking China to Central Asia.

-

The Hexi Corridor and Gansu were contested zones between Chinese dynasties and steppe powers.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

The Medieval Warm Period brought milder steppe conditions, increasing grassland productivity and supporting larger herds.

-

On the Tibetan Plateau, warmer conditions expanded agricultural potential in valleys.

-

Desert oases remained dependent on irrigation, with fluctuating water supplies tied to climate cycles.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Mongol Unification: In the late 12th century, Temüjin (Chinggis Khan) began consolidating Mongolic and Turkic tribes. By 1206, he was proclaimed Chinggis Khan, uniting the Mongols and launching campaigns that expanded into northern China and Central Asia.

-

Tibet: Flourished under the spread of Buddhist monasticism, with schools such as Kadam and early Sakya gaining influence. Tibetan monasteries became centers of learning and landholding, integrating religion and politics.

-

Xinjiang and Tarim Basin: Controlled by the Kara-Khitan (Western Liao, 1124–1218), a Khitan successor state that dominated the region until Mongol conquest.

-

Tangut Xi Xia (1038–1227): A powerful state in the Gansu Corridor, blending Tangut, Tibetan, and Chinese traditions, until it was destroyed by Chinggis Khan.

-

Jurchen Jin dynasty (1115–1234): Controlled parts of Inner Mongolia and northern China, clashing with the Mongols in the early 13th century.

Economy and Trade

-

Pastoralism: Horses, sheep, goats, and camels remained economic foundations in Mongolia.

-

Oasis economies: Silk Road oases produced cereals, fruits, and handicrafts, sustained by irrigation.

-

Tibet: Agro-pastoralism combined barley cultivation with yak herding; monasteries accumulated wealth through land and trade.

-

Long-distance trade: Carried silk, horses, jade, salt, and Buddhist texts across the Silk Road.

-

Tribute and conquest: Mongols reorganized trade into tribute flows, absorbing resources into their growing empire.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Steppe military technology: Composite bows, stirrups, and cavalry tactics gave Mongols decisive advantages.

-

Pastoral innovations: Herding systems balanced mobility and ecological sustainability.

-

Tibetan Buddhism: Monasteries employed printing to reproduce Buddhist texts, spreading doctrine.

-

Silk Road towns: Utilized qanat-style irrigation for oasis agriculture.

-

Mongol military organization: Decimal system (arban, jaghun, mingghan, tumen) created a highly disciplined army.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

The Silk Road through the Tarim Basin linked China, Persia, and Central Asia.

-

Steppe corridors tied Mongolia to both China and Central Asia, enabling rapid Mongol conquests.

-

Tibetan monasteries maintained networks with India, Nepal, and China, reinforcing trans-Himalayan Buddhism.

-

The Hexi Corridor and Xi Xia controlled movement between northern China and the Silk Road.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Mongols: Practiced shamanism and sky worship (Tengri), with Chinggis Khan’s authority legitimized by divine sanction.

-

Tibet: Buddhism flourished, blending tantric traditions with indigenous Bon elements. Monastic centers became powerful both spiritually and politically.

-

Xi Xia and Jin dynasties: Maintained religious pluralism, with Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism present.

-

Religious texts and art flowed along the Silk Road, integrating Buddhist, Islamic, and Christian traditions.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Mongols adapted through mobility, ecological knowledge, and military reorganization, transforming from fragmented tribes into an empire.

-

Tibetan societies balanced agro-pastoralism with monastic economic power.

-

Oasis towns endured climatic stress through irrigation, trade, and caravan networks.

-

Xi Xia and Kara-Khitan demonstrated resilience through cultural fusion, though both succumbed to Mongol conquest.

Long-Term Significance

By 1251 CE, Upper East Asia had been transformed by the rise of the Mongol Empire, reshaping the political map of Eurasia. Tibetan Buddhism expanded as a cultural force, while oasis towns of Xinjiang and the Tarim Basin remained vital Silk Road nodes. The unification of the Mongols under Chinggis Khan created a power that would soon dominate much of Eurasia, making Upper East Asia central to the world-historical shift of the 13th century.

Upper East Asia (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

People

Groups

- Buddhism

- Confucianists

- Buddhism, Tibetan

- Taoism

- Khitan people

- Bon

- Christians, Eastern (Diophysite, or “Nestorian”) (Church of the East)

- Islam

- Tibetan Empire

- Chinese Empire, Tang Dynasty

- Tanguts

- Jurchens

- Liao Dynasty, or Khitan Empire

- Western Xia, or Tangut Kingdom

- Jin Dynasty (Chin Empire), Jurchen

- Kara-Khitan Khanate

- Mongols

- Jin Dynasty (Chin Empire), Jurchen

- Mongol Empire

- Jin Dynasty (Chin Empire), Jurchen

Topics

- Medieval Warm Period (MWP) or Medieval Climate Optimum

- Jurchen Mongol Conquest of the Liao

- Mongol Conquests

- Mongol Conquest of the Song Dynasty

- Mongol invasions of Tibet

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Gem materials

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Fibers

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Aroma compounds

- Stimulants