The western Chalukyas, led in 655 by …

Years: 655 - 655

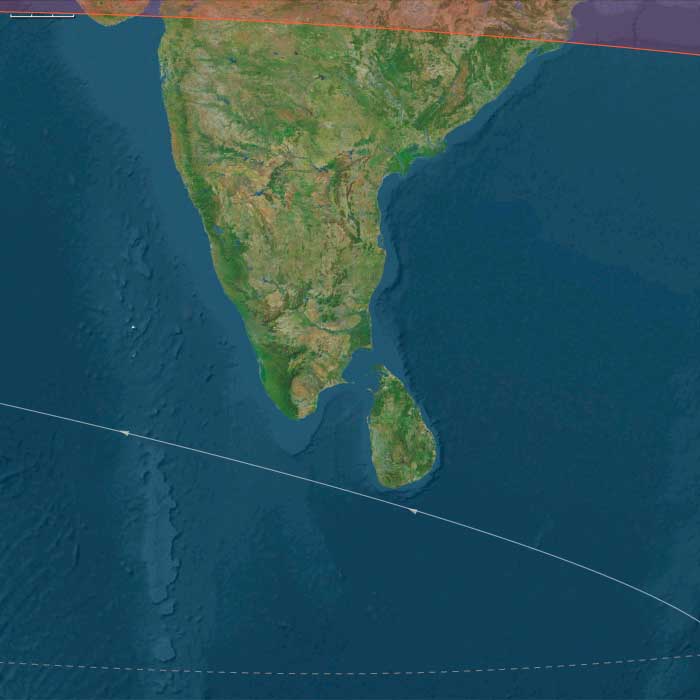

The western Chalukyas, led in 655 by Vikramaditya, recapture Vatapi from the Pallavas and gird themselves for further conflict with the southern dynasty.

Locations

People

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 56356 total

Pope Martin is banished by Constans to the Crimea in May 655, where he will die the following September, honored by the church as a martyr.

A punishment similar to that of Pope Martin is meted out to the theologian Maximus the Confessor, an independent and original thinker who, after imprisonment from 653 to 655, is later tortured and exiled; he will die in 662 in the Lazican wilderness near the Black Sea. (The Greek Orthodox calendar reveres both Martin and Maximus as saints.)

Muawiyah, ruling in Damascus as governor of Syria, continues to develop the Muslims' first naval fleet, his goal the conquest of Constantinople itself.

Muawiyah undertakes an expedition in Cappadocia in 655 while his fleet, under the command of Abdullah ibn Saad, advances along the southern coast of Anatolia.

Emperor Constans II personally commands the imperial flee of five hundred ships and sets off to challenge the Arab navy.

He sails to the province of Lycia in the southern region of Asia Minor.

The two forces meet off the coast of Mount Phoenix, near the harbor of Phoenix (modern Finike).

As the ships come into battle range, Constans raises the Cross and has his men sing psalms.

The Arabs respond by raising the Crescent and trying to drown out the psalms by chanting passages from the Koran.

Both the Cross and Crescent remain mounted on the masts throughout the battle, giving the naval conflict its name.

The Arabs are victorious in battle, although losses are heavy for both sides.

Constans barely escapes to Constantinople, having managed to make his escape, according to Theophanes, by exchanging uniforms with one of his officers.

The Arab fleet retreats after its victory, but the Battle of the Masts is a significant milestone in the history of the Mediterranean, Islam and the Empire, as it establishes the superiority of the Muslims at sea as well as on land.

The Mediterranean for the next four centuries will be a battleground between Constantinople and the Caliphate.

The imperial forces in the aftermath of this disaster are soon granted a respite, however, due to the outbreak of a civil war among the Muslims.

One of Muhammad's secretaries, Zayd Ibn Thabi, is generally believed to have compiled the Qur'an into the unified, authoritative text that is known today, adopted under Uthman’s caliphate.

A group of Egyptian malcontents marches upon Medina, the seat of caliphal authority, in 655.

'Uthman, however, is conciliatory, and the rebels return to Egypt.

Œthelwald in 655 assists Penda during his invasion of Northumbria.

However, when the armies of Oswiu and Penda meet at Cock Beck, near what later will be Leeds, on November 15 at the Battle of the Winwaed, Œthelwald withdraws his forces, as does Cadafael Cadomedd of Gwynedd.

Penda is defeated and killed, perhaps in part because of this desertion, and afterward Œthelwald seems to have lost Deira to Alchfrith, who is installed there by the victorious Oswiu.

Œthelwald's fate is unknown, as nothing is formally recorded of him after the battle.

Local tradition, however, held that he became a hermit in Kirkdale, North Yorkshire.

The battle has a substantial effect on the relative positions of Northumbria and Mercia.

Mercia's position of dominance, established after the battle of Maserfield, is destroyed, and Northumbrian dominance is restored; …

Mercia itself is divided, with the northern part being taken by Oswiu outright and the southern part going to Penda's Christian son Peada, who has married into the Bernician royal line (although Peada will survive only until his murder in 656).

Northumbrian authority over Mercia will be overthrown within a few years, however.

Significantly, the battle of the Winwead marks the effective demise of Anglo-Saxon paganism.

Penda had continued in his traditional paganism despite the widespread conversions of Anglo-Saxon monarchs to Christianity, and a number of Christian kings had suffered death in defeat against him; after Penda's death, Mercia is converted, and all the kings who rule hereafter (including Penda's sons Peada, Wulfhere and Æthelred) are Christian.

Oswiu, now become overlord (bretwalda) over much of Great Britain, establishes himself as king of Mercia, setting up his son-in-law, Penda's son Peada, as a subject king over Middle Anglia.

Peada founds Peterborough Cathedral, which becomes one of the first centers of Christianity in England.

Deusdedit is consecrated as the archbishop of Canterbury.

Atlantic West Europe, 656–667: Merovingian Decline and Rise of Regional Power

The period from 656 to 667 marked a pivotal moment in the Merovingian kingdom of the Franks, as royal authority weakened significantly, allowing local aristocratic families and regional powers to assert greater independence. These developments laid the foundation for future political structures across Atlantic West Europe.

Political and Military Developments

-

Neustria and Austrasia:

- After the death of King Clovis II (657), the kingdom was divided among his sons. Clotaire III became king in Neustria and Burgundy (r. 657–673), while his brother Childeric II ruled Austrasia (r. 662–675).

- Increasing rivalry between these Frankish kingdoms intensified, contributing to political fragmentation.

-

Rise of the Mayors of the Palace:

- The weakening Merovingian monarchy led to the increasing power of aristocratic administrators known as Mayors of the Palace, especially Ebroin in Neustria and Wulfoald in Austrasia. These figures effectively controlled royal authority and dominated internal politics.

-

Aquitaine's Growing Autonomy:

- Aquitaine increasingly functioned as a semi-autonomous region under local dukes, who managed to distance themselves politically and militarily from central Frankish authority.

-

Brittany and Normandy:

- Breton chieftains consolidated control within Brittany, increasingly independent from Merovingian influence.

- The region later known as Normandy saw only intermittent Frankish influence, with limited central oversight.

Economic and Social Developments

- Ruralization and Estate Consolidation:

- Continued growth in large estates controlled by local elites shaped rural society, as the decline of urban centers accelerated the shift toward agrarian-based economies dominated by manorial holdings.

- Localized Trade Networks:

- Long-distance trade declined temporarily; economic activity was primarily regional and local, focused around monasteries and manorial estates.

Religious and Cultural Developments

-

Monastic Expansion and Influence:

- Monastic communities, such as Luxeuil in Burgundy, remained significant centers of learning, manuscript production, and spiritual influence.

- The monasteries provided stability amidst political uncertainty, preserving cultural continuity.

-

Spread of Christianity in Peripheral Regions:

- Continued missionary activities gradually consolidated Christianity in more remote areas, notably Brittany, which still retained elements of Celtic religious traditions alongside the growing Christian influence.

Long-Term Significance

This era laid critical foundations for the political structure of medieval Europe, highlighting the transition from centralized Merovingian royal control to the rise of regional aristocratic governance and autonomy. The weakening of royal authority, combined with the growing strength of local leaders and monasteries, shaped the socio-political landscape of Atlantic West Europe in subsequent decades.

Empress Saimei builds a new palace at Asuka because her former residence had burned in a fire.

This construction is called the "Mad Canal" by the people, as it is seen as wasting the labor of tens of thousand workers and a large amount of money.