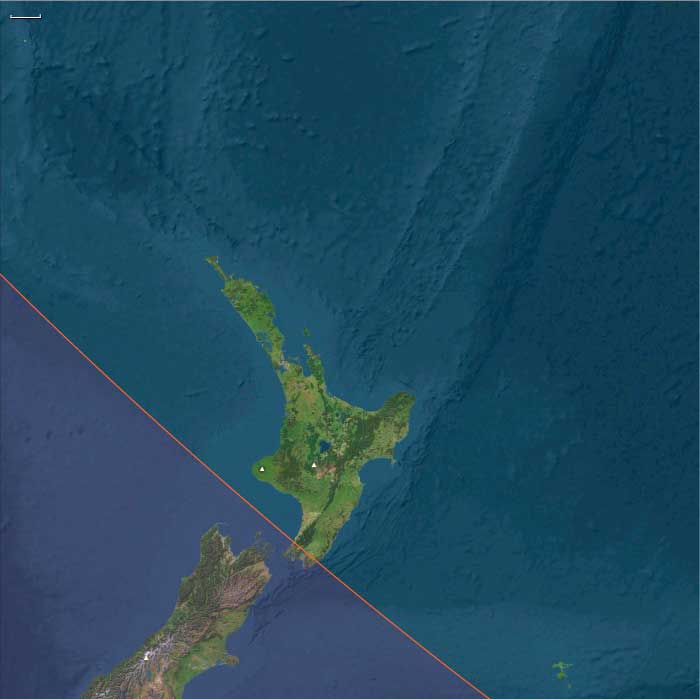

The new Maori kingdom begins to clash …

Years: 1852 - 1863

The new Maori kingdom begins to clash with land-hungry colonists.

Groups

- Aotearoa

- Maori people

- Britain (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland)

- New Zealand, (British) Crown Colony of

- New Zealand, British Colony of

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 521 total

The United States has warned that recognition will mean war.

However, the textile industry needs Southern cotton, and Napoleon has imperial ambitions in Mexico, which can be greatly aided by the Confederacy.

At the same time, other French political leaders, such as Foreign Minister Édouard Thouvenel, support the United States.

Napoleon helps finance the Confederacy but refuses to intervene actively until Britain agrees, and London always rejects intervention.

The Emperor realizes that a war with the US without allies would spell disaster for France.

The support France gives to the Italian cause has aroused the eager hopes of other nations.

The proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy on March 17, 1861 after the rapid annexation of Tuscany and the kingdom of Two Sicilies has proved the danger of half-measures, but when a concession, however narrow, has been made to the liberty of one nation, it can hardly be refused to the no less legitimate aspirations of the rest.

In 1863, these "new rights" again clamor loudly for recognition: in Poland, in Schleswig and Holstein, in Italy, now united, with neither frontiers nor capital, and in the Danubian principalities.

To extricate himself from the Polish impasse, the emperor again proposes a congress, with no luck.

He is again unsuccessful: Great Britain refuses even to admit the principle of a congress, while Austria, Prussia and Russia give their adhesion only on conditions which render it futile, i.e., they reserve the vital questions of Venetia and Poland.

The Emperor support of the Polish rebels alienates the Russian leadership.

The visit of Czar Alexander II to Paris becomes a disaster when he is twice attacked by Polish assassins, though he escapes.

In Berlin, Bismarck sees the opportunity to squeeze out the French by forming closer relationships with the Russians.

The conquest is bloody but successful, and supported by large numbers of French soldiers, missionaries and businessmen, as well as the local Chinese entrepreneurial element.

He helps to rapidly promote rapid economic modernization, but his army battles diehard insurgents who have American support.

By 1863, French military intervention in Mexico to set up a Second Mexican Empire headed by Emperor Maximilian, brother of Franz Joseph I of Austria, is a complete fiasco.

The Mexicans fight back and after defeating the Confederacy the U.S. will demand the French withdraw from Mexico—sending fifty thousand veteran combat troops to the border to ram the point home.

The French army will go home; the puppet emperor does not leave and will eventually be executed.

Thus both Catholics and protectionists discover that authoritarian rule can be favorable when it serves their ambitions or interests, but not when exercised at their expense.

He begins by removing the gag that has kept the country in silence.

On November 24, 1860, he grants to the Chambers the right to vote an address annually in answer to the speech from the throne, and to the press the right of reporting parliamentary debates.

He counts on the latter concession to hold in check the growing Catholic opposition, which is becoming more and more alarmed by the policy of laissez-faire practiced by the emperor in Italy.

The government majority already shows some signs of independence.

The right of voting on the budget by sections, granted by the emperor in 1861, is a new weapon given to his adversaries.

Everything conspires in their favor: the anxiety of those candid friends who are calling attention to the defective budget, the commercial crisis and foreign troubles.

Napoleon III multiplies French interventions abroad, especially in Crimea, in Mexico and Italy, which result in the annexation of the duchy of Savoy and the county of Nice, formerly part of the Kingdom of Sardinia.

His son Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte is born the same year, which promises a continuation of the dynasty.

In 1859, Napoleon leads France to war with Austria over Italy.

France is victorious and gains Savoy and Nice.

Legally he has broad powers but in practice he is limited by legal, customary, and moral deterrents.

By 1851 political police had had a centralized administrative hierarchy and were largely immune from public control.

The Second Empire has continued the system; proposed innovations are stalled by officials.

Typically political roles are part of routine administrative duties.

Although police forces have indeed been strengthened, opponents exaggerate the increase of secret police activity and the imperial police lacks the omnipotence seen in later totalitarian states.

A keen Catholic opposition springs up, voiced in Louis Veuillot's paper the Univers, and is not silenced even by the Syrian expedition (1860) in favor of the Catholic Maronite side of the Druze–Maronite conflict.

Ultramontane Catholicism, emphasizing the necessity for close links to the Pope at the Vatican, plays a pivotal role in the democratization of culture.

The pamphlet campaign led by Mgr. Gaston de Ségur at the height of the Italian question in February 1860 makes the most of the freedom of expression enjoyed by the Catholic Church in France.

The goal is to mobilize Catholic opinion, and encourage the government to be more favorable to the Pope.

A major result of the Ultramontane campaign is to trigger reforms to the cultural sphere, and the granting of freedoms to their political enemies: the Republicans and freethinkers.

The Second Empire strongly favors Catholicism, the official state religion.

However, it tolerates Protestants and Jews, and there are no persecutions or pogroms.

The state deals with the small Protestant community of Calvinist and Lutheran churches, whose members include many prominent businessmen who support the regime.

The emperor's Decree Law of March 26, 1852 had led to greater government interference in Protestant church affairs, thus reducing self-regulation.

Catholic bureaucrats both misunderstand Protestant doctrine and are biased against it.

The administration of their policies affects not only church-state relations but also the internal lives of Protestant communities.

Napoleon III, with near-dictatorial powers, makes building a good railway system a high priority.

He consolidates three dozen small, incomplete lines into six major companies using Paris as a hub.

Paris grows dramatically in terms of population, industry, finance, commercial activity, and tourism. Working with Georges-Eugène Haussmann from 1853, Napoleon III spends lavishly to rebuild the city into a world-class showpiece.

The financial soundness for all six companies is solidified by government guarantees.

Although France had started late, by 1870 it will have an excellent railway system, supported as well by good roads, canals and ports.

Napoleon, in order to restore the prestige of the Empire before the newly awakened hostility of public opinion, tries to gain the support from the Left that he had lost from the Right.

After the return from Italy, the general amnesty of August 16, 1859, marks the evolution of the absolutist or authoritarian empire towards the liberal, and later parliamentary empire, which will last for ten years.

Years: 1852 - 1863

Groups

- Aotearoa

- Maori people

- Britain (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland)

- New Zealand, (British) Crown Colony of

- New Zealand, British Colony of