Sri Lanka's earliest archaeological evidence of human …

Years: 35469BCE - 33742BCE

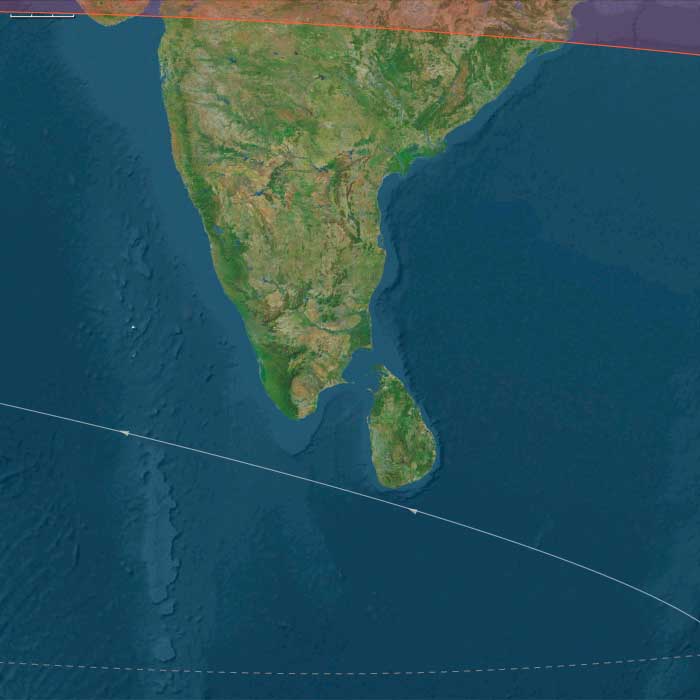

Sri Lanka's earliest archaeological evidence of human colonization appears at the site of Balangoda, whose Mesolithic hunter gatherers arrived on the island about thirty-four thousand years ago and lived in caves, several of which have yielded many artifacts from these people, currently the first known inhabitants of the island.

Locations

Groups

Topics

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 69594 total

A four-hole flute, excavated in September 2008 from a German cave, is the oldest handmade musical instrument ever found, according to archaeologist Nicholas Conrad, who assembled the flute from twelve pieces of griffon vulture bone scattered in the Hohle Fels, a cave in the Swabian Alps of Germany.

At a news conference on June 24, 2012, Conrad said the 8.6-inch flute was crafted thirty-five thousand years ago.

The flutes found in the Hohle Fels are among the earliest musical instruments ever found.

The Swabian Alb region has a number of caves that have yielded mammoth ivory artifacts of the Upper Paleolithic period, totaling about twenty-five items to date.

These include the lion-headed figure of Hohlenstein-Stadel and an ivory flute found at Geißenklösterle, dated to thirty-six thousand years ago.

This concentration of evidence of full behavioral modernity in the period of forty to thirty thousand years ago, including figurative art and instrumental music, is unique worldwide.

Nicholas J. Conard speculates that the bearers of the Aurignacian culture in the Swabian Alb may be credited with the invention, not just of figurative art and music, but possibly, early religion as well.

In a distance of seventy centimeters to the Venus figurine, Conard's team found a flute made from a vulture bone.

Additional artifacts excavated from the same cave layer included flint-knapping debris, worked bone, and carved ivory as well as remains of tarpans, reindeer, cave bears, woolly mammoths, and Alpine Ibexes.

A lion headed figure, first called the lion man (German: Löwenmensch, literally "lion person"), then the lion lady (German: Löwenfrau), is an ivory sculpture that is the oldest known zoomorphic (animal-shaped) sculpture in the world and one of the oldest known sculptures in general.

The sculpture has also been interpreted as anthropomorphic, giving human characteristics to an animal, although it may have represented a deity.

The figurine was determined to be about thirty-two thousand years old by carbon dating material from the same layer in which the sculpture was found.

It is associated with the archaeological Aurignacian culture.

Its pieces were found in 1939 in a cave named Stadel-Höhle im Hohlenstein (Stadel cave in Hohlenstein Mountain) in the Lonetal (Lone valley) Swabian Alb, Germany.

Due to the beginning of the Second World War, it was forgotten and only rediscovered thirty years later.

The first reconstruction revealed a humanoid figurine without head.

During 1997 through 1998, additional pieces of the sculpture were discovered and the head was reassembled and restored.

The sculpture, 29.6 centimeters (11.7 inches) in height, 5.6 centimeters wide, and 5.9 centimeters thick, was carved out of mammoth ivory using a flint stone knife.

There are seven parallel, transverse, carved gouges on the left arm.

After this artifact was identified, a similar, but smaller, lion-headed sculpture was found, along with other animal figures and several flutes, in another cave in the same region of Germany.

This leads to the possibility that the lion-figure played an important role in the mythology of humans of the early Upper Paleolithic.

The sculpture can be seen in the Ulmer Museum in Ulm, Germany.

Australian aboriginal people show considerable genetic diversity but are quite distinct from groups outside Australia.

Having come originally from somewhere in Asia, they have been in Australia for at least forty thousand years.

Most of the continent, including the southwest and southeast corners as well as the Highlands of the island of New Guinea, was occupied by thirty thousand years before the present.

The Aurignacian Tool Industry (32,000–27,000 BCE)

The Aurignacian tool industry, named after the site of Aurignac in France, flourished between 32,000 and 27,000 BCE, marking a significant phase in Upper Paleolithic technology. This industry is associated with Early European Modern Humans (EEMH) and represents a notable advancement in stone tool production and artistic expression.

Key Characteristics of Aurignacian Tools

- Parallel fluting along the entire margin of tools, a defining feature of Aurignacian craftsmanship.

- Increased use of blades (long, thin flakes of stone) instead of the broader flakes characteristic of earlier tool traditions.

- Bone and antler tools, including awls, points, and needles, reflecting a diversification of materials.

- The emergence of carved figurines, beads, and engravings, suggesting a growing symbolic and artistic culture.

Cultural and Technological Impact

The Aurignacian industry played a crucial role in the spread of modern humans across Europe and is often associated with the displacement of Neanderthals. The refined tool-making techniques and the appearance of early art and symbolic artifacts suggest a complex cognitive and cultural framework, setting the stage for further advances in Upper Paleolithic societies.

Australia by 30,000 BCE has already been inhabited for, at minimum, twenty thousand years by the aboriginal people.

Modern humans reach East Asia (Korea, Japan) around thirty thousand years BP.

Archaeologists also find evidence of Stone Age technology in Aq Kopruk and Hazar Sum in north central Afghanistan.

Plant remains in the foothills of the Hindu Kush mountains indicate that northern Afghanistan is one of the earliest places to domestic plants and animals.

Paleolithic peoples had probably roamed Afghanistan as early as 100,000 BCE.

A cave at Darra-i-Kur in Badakhshan, where twentieth-century archaeologists will discover a transitional Neanderthal skull fragment in association with Mousterian-type tools, is the earliest definite evidence of human occupation; the remains are of the Middle Paleolithic, dating about 30,000 years BCE.

The questions of how, when, and why the first peoples entered the Americas remain subjects of active research, though recent genomic advances have significantly refined our understanding. While there is general agreement that the Americas were first settled by peoples who migrated from Asia across Beringia, the migration patterns, timing, and genetic origins have proven far more complex than previously recognized.

Archaeological evidence suggests that widespread human habitation of the Americas occurred during the late glacial period (roughly 16,500-13,000 years ago), following the Last Glacial Maximum. However, sites like White Sands, New Mexico, suggest human presence as early as 21,000-23,000 years ago, potentially during the height of glaciation.

Whole-genome studies have revolutionized understanding of Native American origins, revealing that while most ancestry stems from a shared founding population, at least four distinct streams of Eurasian migration contributed to present-day and prehistoric Native American populations. Ancient DNA analysis of individuals like the 12,600-year-old Anzick-1 child (associated with Clovis artifacts) confirms genetic continuity between early inhabitants and modern Native Americans, contradicting theories of population replacement.

Current research supports a model involving initial migration from a structured Northeast Asian source population, followed by a period of isolation in Beringia, and subsequent coastal migration into the Americas. This founding population then diversified within the continent, splitting into northern and southern lineages around 14,500-17,000 years ago. Additionally, some Amazonian populations show genetic signatures suggesting ancestry from a second source related to indigenous Australasians, indicating an even more complex founding history.

Rather than simple single versus multiple migration models, the genetic evidence points to a nuanced process involving multiple ancestral streams, periods of isolation, rapid expansion, and subsequent diversification within the Americas.