Southern South Atlantic (7,821–6,094 BCE): Early Holocene …

Years: 7821BCE - 6094BCE

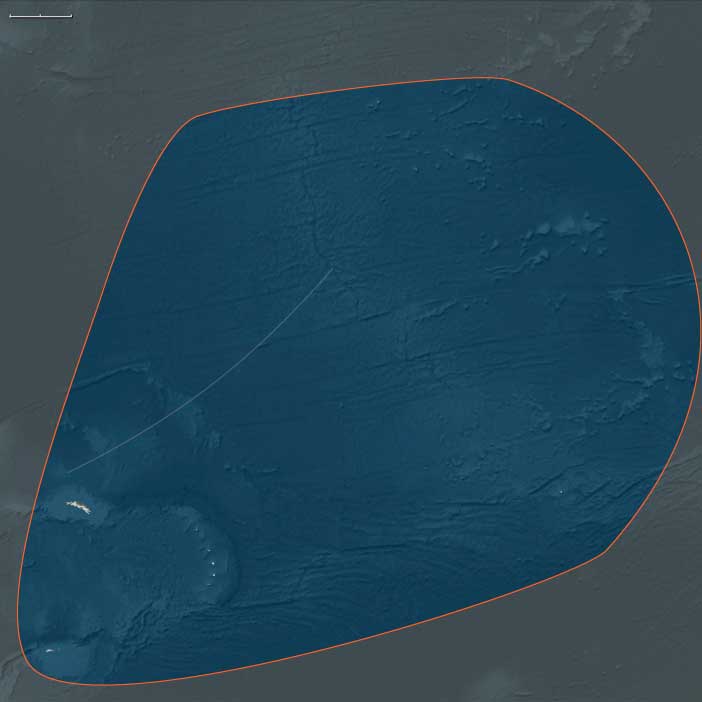

Southern South Atlantic (7,821–6,094 BCE): Early Holocene Seas and Expanding Habitats

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of Southern South Atlantic includes the Tristan da Cunha archipelago, Bouvet Island, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, and the South Orkney Islands (including Coronation Island). These islands, volcanic and glaciated, were scattered across the roaring South Atlantic. Tristan da Cunha and Goughfeatured rugged volcanic peaks with expanding tundra-like vegetation zones. Bouvet remained ice-draped, its small volcanic cone surrounded by stormy seas. South Georgia and the South Orkneys were still dominated by glaciers but showed widening belts of ice-free coastlines, fjords, and headlands.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

This was the early Holocene, when warming temperatures followed the last great glaciation. By this epoch, sea level had risen close to modern levels, drowning exposed shelves and reshaping island coastlines. Glaciers retreated across South Georgia and the South Orkneys, though substantial ice caps persisted. The climate was cool, wet, and windy, dominated by strong westerlies and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), but markedly milder than during the glacial age.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human settlement yet reached these remote islands. Ecological communities expanded as warming created new habitats. Tussock grasslands, mosses, lichens, and small flowering plants spread on Tristan, Gough, and the fringes of South Georgia. Penguin colonies (king, gentoo, macaroni) multiplied along newly exposed coasts. Seals established denser haul-outs, while offshore krill swarms, fish, and squid supported booming populations of seabirds and whales. The South Sandwich Islands and Bouvet, still heavily ice-clad, remained less hospitable but supported seabirds and seals in coastal niches.

Technology & Material Culture

In other parts of the world, Holocene humans were developing farming, domesticating animals, and advancing stone tool traditions. Yet the Southern South Atlantic remained completely untouched by human technology. Its ecosystems developed entirely without human interference, making them some of the most pristine environments on Earth.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The region was an ecological crossroads. The ACC distributed nutrients across the islands, sustaining marine productivity. Seasonal whale migrations brought baleen species south in summer to feed in krill-rich waters before they traveled north in winter. Seabirds, especially albatrosses and petrels, ranged across hemispheric distances, linking the islands with South America, Africa, and Antarctica. Penguins and seals expanded with ice retreat, colonizing new beaches and rocky ledges.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human cultural or symbolic frameworks attached to these islands in this epoch. Symbolism was ecological: rookeries, breeding colonies, and seasonal whale gatherings marked continuity and renewal across generations.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Life showed remarkable adaptability. Plants colonized deglaciated soils, anchoring landscapes against erosion. Penguins and seals redistributed breeding sites as glaciers pulled back and sea-ice cycles shifted. Krill populations adapted to reduced winter sea ice by concentrating under remaining ice canopies and in upwelling zones, sustaining the broader food web.

Transition

By 6,094 BCE, the Southern South Atlantic was firmly within the Holocene. Ice continued to retreat, vegetation was expanding, and wildlife thrived in newly opened habitats. Humans still knew nothing of these islands, but their ecological richness was already fully established, shaped by winds, currents, and the rhythms of the Southern Ocean.