Parts of the region now called Cambodia …

Years: 45BCE - 99

Parts of the region now called Cambodia were inhabited during the first and second millennia BCE, by peoples having a Neolithic culture, as indicated by archaeological evidence.

By the first century CE, the inhabitants have developed relatively stable, organized societies, which have far surpassed the primitive stage in culture and technical skills.

The most advanced groups live along the coast and in the lower Mekong River valley and delta regions, where they cultivate irrigated rice and keep domesticated animals.

Scholars believe that these people may have been Austroasiatic in origin and related to the ancestors of the groups who now inhabit insular Southeast Asia and many of the islands of the Pacific Ocean.

They work metals, including both iron and bronze, and possess navigational skills.

Mon-Khmer people, who arrived at a later date, have probably intermarried with them.

The Khmer who now populate Cambodia may have migrated from southeastern China to the Indochinese Peninsula before the first century CE.

They are believed to have arrived before their present Vietnamese, Thai, and Lao neighbors.

Groups

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 62463 total

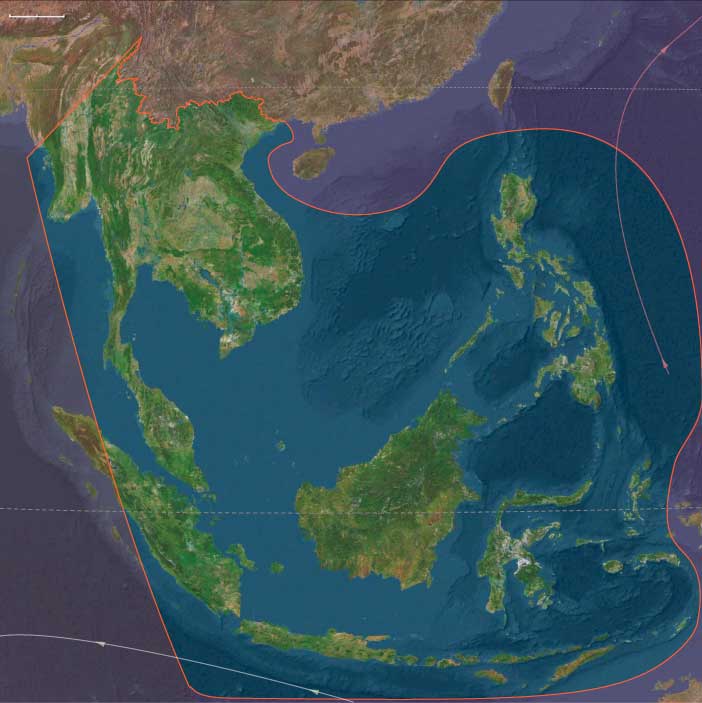

Many parts of the Indonesian archipelago play a role in local and wider trading networks from early times, and some are further connected to interregional routes reaching much farther corners of the globe.

Nearly four thousand years ago, cloves—which until the seventeenth century grow nowhere else in the world except five small islands in Maluku—had made their way to kitchens in present-day Syria.

By about the same time, items such as shells, pottery, marble, and other stones; ingots of tin, copper, and gold; and quantities of many food goods are traded over a wide area in Southeast Asia.

As early as the fourth century BCE, materials from South Asia, the Mediterranean world, and China—ceramics, glass and stone beads, and coins—begin to show up in the archipelago.

In the already well-developed regional trade, bronze vessels and other objects, such as the spectacular kettledrums produced first in Dong Son (northern Vietnam), circulated in the island world, appearing after the second century BCE from Sumatra to Bali and from Kalimantan and Sulawesi to the eastern part of Maluku.

Around two thousand years ago, Javanese and Balinese are themselves producing elegant bronze ware, which is traded widely and has been found in Sumatra, Madura, and Maluku.

In all of this trade, including that with the furthest destinations, peoples of the archipelago appear to have dominated, not only as producers and consumers or sellers and buyers, but as shipbuilders and owners, navigators, and crew.

The principal dynamic originated in the archipelago.

This is an important point, for historians have often mistakenly seen both the trade itself and the changes that stemmed from it in subsequent centuries as primarily the work of outsiders, leaving Indonesians with little historical agency, an error often repeated in assessing the origins and flow of change in more recent times as well.

Vietnam is governed leniently during the first century or so of Chinese rule, and the Lac lords maintain their feudal offices.

In the first century CE, however, China intensifies its efforts to assimilate its new territories by raising taxes and instituting marriage reforms aimed at turning Vietnam into a patriarchal society more amenable to political authority.

In response to increased Chinese domination, a revolt breaks out in Giao Chi, Cuu Chan, and Nhat Nam in CE 39, led by Trung Trac, the wife of a Lac lord who had been put to death by the Chinese, and her sister Trung Nhi.

The insurrection is put down within two years by the Han general Ma Yuan, and the Trung sisters drown themselves to avoid capture by the Chinese.

Still celebrated as heroines by the Vietnamese, the Trung sisters exemplify the relatively high status of women in Vietnamese society as well as the importance to Vietnamese of resistance to foreign rule.

In order to facilitate administration of their new territories, the Chinese build roads, waterways, and harbors, largely with corvée labor (unpaid labor exacted by government authorities, particularly for public works projects).

Agriculture is improved with better irrigation methods and the use of plows and draft animals, innovations which may have already been in use by the Vietnamese on a lesser scale.

New lands are opened up for agriculture, and settlers are brought in from China.

After a few generations, most of the Chinese settlers probably intermarry with the Vietnamese and identify with their new homeland.

At about the time that the ancient peoples of Western Europe are absorbing the classical culture and institutions of the Mediterranean, the peoples of mainland and insular Southeast Asia are responding to the stimulus of a civilization that had arisen in northern India during the previous millennium.

The Britons, Gauls, and Iberians experience Mediterranean influences directly, through conquest by and incorporation into the Roman Empire.

In contrast, the Indianization of Southeast Asia is a slower process than the Romanization of Europe because there is no period of direct Indian rule and because land and sea barriers that separate the region from the Indian subcontinent are considerable.

Nevertheless, Indian religion, political thought, literature, mythology, and artistic motifs gradually become integral elements in local Southeast Asian cultures.

The caste system never is adopted, but Indianization stimulates the rise of highly-organized, centralized states.

Chinese rule over the Vietnamese becomes more direct following the ill-fated revolt, and the feudal Lac lords fade into history.

Ma Yuan establishes a Chinese-style administrative system of three prefectures and fifty-six districts ruled by scholar-officials sent by the Han court.

Although Chinese administrators replace most former local officials, some members of the Vietnamese aristocracy are allowed to fill lower positions in the bureaucracy.

The Vietnamese elite in particular receive a thorough indoctrination in Chinese cultural, religious, and political traditions.

One result of Sinicization, however, is the creation of a Confucian bureaucratic, family, and social structure that give the Vietnamese the strength to resist Chinese political domination in later centuries, unlike most of the other Yue peoples who are sooner or later assimilated into the Chinese cultural and political world.

Nor is Sinicization so total as to erase the memory of pre-Han Vietnamese culture, especially among the peasant class, which retains the Vietnamese language and many Southeast Asian customs.

Chinese rule has the dual effect of making the Vietnamese aristocracy more receptive to Chinese culture and cultural leadership while at the same time instilling resistance and hostility toward Chinese political domination throughout Vietnamese society.

The inhabitants of the region of present Cambodia have by the first century CE developed relatively stable, organized societies that have far surpassed the primitive stage in culture and technical skills.

The most advanced groups live along the coast and in the lower Mekong River valley and delta regions where they cultivate rice and keep domesticated animals.

The Khmer, like the other early peoples of Southeast Asia such as the Pyu, Mon, Cham, Malay and Javanese, are influenced by Indian and Sri Lankan traders and scholars, adapting their religions, sciences, and customs and borrowing from their languages.

The Khmer also acquire the concept of the Shaivite Deva Raja (God-King) and the great temple as a symbolic holy mountain.

Maritime East Asia (45 BCE–99 CE): Dynastic Turmoil, Regional Influence, and Rebellions

Between 45 BCE and 99 CE, Maritime East Asia—comprising lower Primorsky Krai, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese Archipelago below northern Hokkaido, Taiwan, and southern, central, and northeastern China—experiences significant political upheavals, regional expansions, and continued cultural and technological advancements during the later Han dynasty.

Political Instability and Dynastic Change

The early first century CE is marked by dynastic turbulence, most notably during Wang Mang's Xin Dynasty. Major agrarian rebellions originating in modern Shandong and northern Jiangsu drain the Xin dynasty’s resources, eventually leading to Wang Mang’s overthrow. The Lülin rebellion elevates Liu Xuan (Emperor Gengshi) to briefly restore the Han dynasty. However, internal divisions soon see Gengshi replaced by the Chimei faction's puppet emperor, Liu Penzi, who himself falls due to administrative incompetence.

By 30 CE, the Eastern Han dynasty under Emperor Guangwu (Liu Xiu) reestablishes control, overcoming these rebellions and restoring a degree of central authority.

Expansion and Influence in Korea

Lelang (Nangnang), near present-day P'yongyang, becomes a significant center of Chinese governance, culture, industry, and commerce, maintaining its prominence for approximately four centuries. Its extensive influence draws Chinese immigrants and imposes tributary relationships on several Korean states south of the Han River, shaping regional civilization and governance.

The Korean Peninsula witnesses substantial agrarian development, notably through advanced rice agriculture and extensive irrigation systems. By the first three centuries CE, walled-town states cluster into three federations: Jinhan, Mahan, and Byeonhan, marking significant strides toward regional organization and agricultural efficiency.

Goguryeo and Han Relations

During the instability of Wang Mang’s rule, the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo exploits the turmoil, frequently raiding Han's Korean prefectures. It is not until 30 CE that Han authority is firmly restored, reasserting control over these border territories.

Xiongnu and Frontier Conflicts

Wang Mang's hostile policy toward the northern nomadic Xiongnu tribes culminates in significant frontier conflicts. By 50 CE, internal division splits the Xiongnu into the Han-allied Southern Xiongnu and the antagonistic Northern Xiongnu. The Northern Xiongnu seize control of the strategically important Tarim Basin in 63 CE, threatening Han’s crucial Hexi Corridor.

However, following their defeat in 91 CE, the Northern Xiongnu retreat into the Ili River valley, allowing the Xianbei nomads to occupy extensive territories from Manchuria to the Ili River, reshaping regional power dynamics.

Technological and Cultural Developments

This period sees continued advancements in mathematics and commerce. Notably, the influential Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art (Jiu Zhang Suan Shu) documents the first known use of negative numbers, employing distinct color-coded counting rods to represent positive and negative values, and presenting sophisticated methods for solving simultaneous equations.

Peak and Decline under Emperor Zhang

The reign of Emperor Zhang (75–88 CE) is retrospectively regarded as the Eastern Han dynasty's zenith, characterized by administrative stability and cultural flourishing. However, subsequent emperors witness increasing eunuch interference in court politics, sparking violent power struggles between eunuchs and imperial consort clans, foreshadowing dynastic decline.

Legacy of the Age: Turbulence, Expansion, and Innovation

Thus, the age from 45 BCE to 99 CE is defined by significant political turbulence, territorial expansion, technological innovation, and sustained cultural influence. Despite internal strife, this era reinforces critical foundations for subsequent East Asian civilizations, shaping regional dynamics profoundly.

Lelang is a great center of Chinese statecraft, art, industry (including the mining of iron ore), and commerce for about four centuries, from the second century BCE to the second century CE.

Its influence is far-reaching, attracting immigrants from China and exacting tribute from several states south of the Han River, which pattern their civilization and government after Lelang.

In the first three centuries CE, a large number of walled-town states in southern Korea have grouped into three federations known as Jinhan, Mahan, and Byeonhan; rice agriculture has developed in the rich alluvial valleys and plains to the point of establishing reservoirs for irrigation.

Major agrarian rebellion movements against Wang Mang's Xin Dynasty, initially active in the modern Shandong and northern Jiangsu region, eventually lead to Wang Mang's downfall by draining his resources; this allows the leader of the other movement (the Lülin), Liu Xuan (Emperor Gengshi) to overthrow Wang and temporarily establish an incarnation of the Han Dynasty under him.

Chimei forces eventually overthrow Emperor Gengshi and place their own Han descendant puppet, Emperor Liu Penzi, on the throne, but briefly: the Chimei leaders' incompetence in ruling the territories under their control, which matches their brilliance on the battlefield, causes the people to rebel against them, forcing them to try to withdraw homeward.

They surrender to Liu Xiu's (Emperor Guangwu’s) newly established Eastern Han regime when he blocks their path.

The state of Goguryeo had been free to raid Han's Korean prefectures during the widespread rebellion against Wang Mang; the Han dynasty does not reaffirm its control over the region until CE 30.

The rebellion led by the Trung Sisters of Vietnam is crushed after a few years.

Wang Mang had renewed hostilities against the Xiongnu, who are estranged from Han until their leader, a rival claimant to the throne against his cousin, submits to Han as a tributary vassal in 50.

This creates two rival Xiongnu states: the Southern Xiongnu led by a Han ally, and the Northern Xiongnu led by a Han enemy.

During the turbulent reign of Wang Mang, Han had lost control over the Tarim Basin, which is conquered by the Northern Xiongnu in 63 and used as a base to invade Han's Hexi Corridor in Gansu.

After the Northern Xiongnu defeat and flight into the Ili River valley in 91, the nomadic Xianbei occupy the area from the borders of the Buyeo Kingdom in Manchuria to the Ili River of the Wusun people.

The reign of Emperor Zhang, from 75–88, will come to be viewed by later Eastern Han scholars as the high point of the dynastic house.

Subsequent reigns will be increasingly marked by eunuch intervention in court politics and their involvement in the violent power struggles of the imperial consort clans.

The Xiongnu finally had been driven back into their homeland by the Chinese in CE 48, but within ten years the Xianbei (or Hsien-pei in Wade-Giles) had moved (apparently from the north or northwest) into the region vacated by the Xiongnu.

The Xianbei are the northern branch of the Donghu (or Tung Hu, the Eastern Hu), a proto-Tungus group mentioned in Chinese histories as existing as early as the fourth century BC E.

The language of the Donghu, like that of the Xiongnu, is unknown to modern scholars.

The Donghu had been among the first peoples conquered by the Xiongnu.

Once the Xiongnu state weakens, however, the Donghu rebel.