Southern Africa (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early …

Years: 7821BCE - 6094BCE

Southern Africa (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Flood Pulses, Forested Shores, and a Golden Age of Image and Song

Geographic & Environmental Context

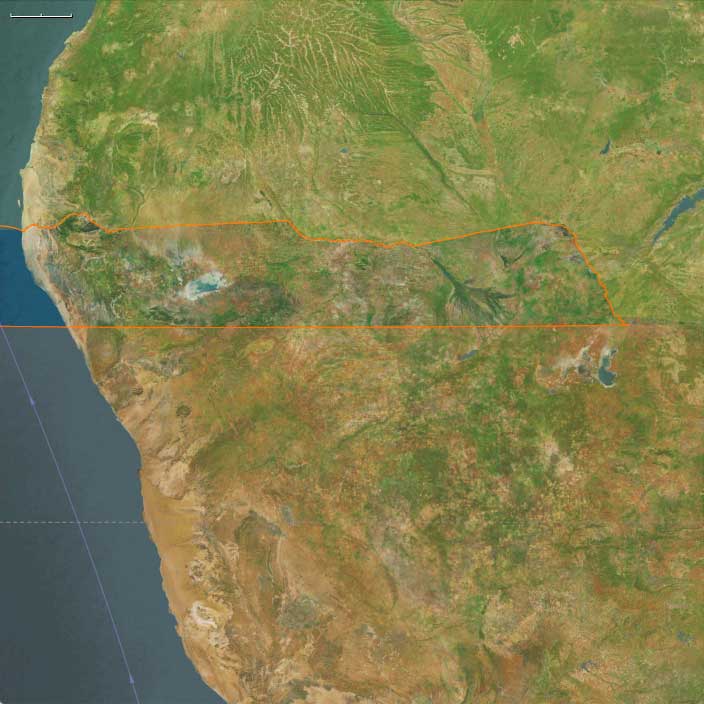

During the Early Holocene, Southern Africa cohered as a single hydrological tapestry: the Cape littoral and fynbos, Highveld grasslands and the Drakensberg–Lesotho massif, the Karoo and Namaqualand margins, and—northward—the Okavango–Zambezi–Chobe–Caprivi floodplains, Etosha’s pan–spring system, and the fog-nourished Skeleton Coast.

Warmer, wetter conditions raised river stages and swelled wetlands; grasslands were lush; estuaries and rocky coves along the Cape brimmed with marine life. Across both Temperate Southern Africa and Tropical West Southern Africa, landscapes stabilized into reliable seasonal engines that anchored larger, longer-lived forager settlements than in the late Pleistocene.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal optimum brought stable, warm, moisture-rich regimes:

-

In the temperate south, dependable rainfall fed perennial streams, seeps, and valley wetlands; fynbos productivity surged.

-

In the tropical north, predictable flood pulses coursed through the Okavango and Caprivi distributaries; Etosha oscillated between shallow waters and saline playa fringed by thornveld.

-

Coastal upwelling and surf-exposed shores along the Cape ensured year-round shellfish and fish abundance.

This hydroclimatic equilibrium supported semi-sedentary anchoring at rivers, levees, pans, and coves, with seasonal forays that stitched biomes together.

Subsistence & Settlement

A continental portfolio subsistence matured, combining permanence with mobility:

-

Temperate belts (Cape–Highveld–Drakensberg–Karoo/Namaqualand): large seasonal villages formed on rivers and coastal terraces. Diets blended shellfish, intertidal fish, and waterfowl with nuts, geophytes, fruits, and antelope from grassland and fynbos ecotones.

-

Tropical floodplains and pans (Okavango–Caprivi–Etosha): levee hamlets worked fish weirs/traps, netted waterfowl, drove floodplain antelope, and harvested reed rhizomes and water-lilies; spring-edge camps around Etosha paired small-game hunts with seed and tuber gathering.

Across both spheres, households returned to the same “home” nodes (levees, springs, dune bars, caves), building place memory and routinized storage.

Technology & Material Culture

Toolkits were light, durable, and water-savvy:

-

Microlithic composite arrows with widespread bows; grinding slabs, bone awls, and sinew thread for leather and net repair.

-

Nets, basketry fish traps, and stake weirs in floodplains and estuaries; dugout or raftlike craft in calm reaches.

-

Ostrich eggshell (OES) flasks for water transport and abundant OES beads as exchange tokens.

-

Pottery remains unlikely this early in these zones, but organic containers and smoke-drying racks left a strong storage signature.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Mobility braided uplands, lowlands, and coasts into one exchange field:

-

The Drakensberg–Highveld–Limpopo axis funneled hides, pigments, shell ornaments, and dried foods between mountains, plateau, and river basins.

-

In the north, flood-ridge “causeways” among palm islands, Zambezi–Chobe canoe drifts, and Omuramba paths around Etosha linked seasonal camps.

-

Cape coastal strips connected shell-rich coves with inland valleys; bead trails—especially OES bead chains—traced kin and ritual ties over long distances.

These routes produced redundancy: when a run failed or a pan dried, another habitat or partner settlement filled the gap.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

The period witnessed a rock-art fluorescence unparalleled in its symbolic density:

-

In the Drakensberg and Cape ranges, finely shaded polychromes depicted animal–human spiritual scenes, trance dances, and eland-centered ceremonies, encoding rainmaking, healing, and transformation.

-

On northern pans and springs, bead caches, structured hearths, and healing/rain rites anchored settlement memory; trance traditions deepened with flood-pulse rhythms.

-

Along the coasts, shell-midden feasts functioned as ancestral monuments, renewing access rights to fisheries and foraging grounds.

Ritual did more than reflect subsistence—it governed access, timed movement, and knit far-flung camps into moral communities.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Households engineered security through storage, scheduling, and multi-ecotone use:

-

Smoke-dried fish, dried meats, roasted seeds and nuts, and rendered fats sustained overwintering and dry-season gaps.

-

Seasonal rounds (coast/river ↔ upland/pan) buffered climate noise; island refugia in the Okavango and spring mounds at Etosha offered drought insurance.

-

Tenure customs, marked by shrines, art, and feasting places, regulated pressure on key stocks (weirs, shell banks, berry groves), limiting conflict and overtake.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Southern Africa had crystallized into a symbolically rich, storage-capable forager world: large seasonal villages on rivers and coasts in the south; flood-pulse hamlets and spring-edge camps in the north—each tied by exchange corridors and a shared ritual grammar.

These lifeways—portfolio subsistence, water-anchored settlement, bead-mediated alliances, and shrine-marked tenure—formed the durable substrate on which later herding frontiers (visible on distant horizons) and farmer networks would graft, without erasing the region’s deep art of place.

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Colorants

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Strategic metals