Southern Africa (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle …

Years: 6093BCE - 4366BCE

Southern Africa (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Abundance, Ceremony, and the Mapping of Sacred Land

Geographic & Environmental Context

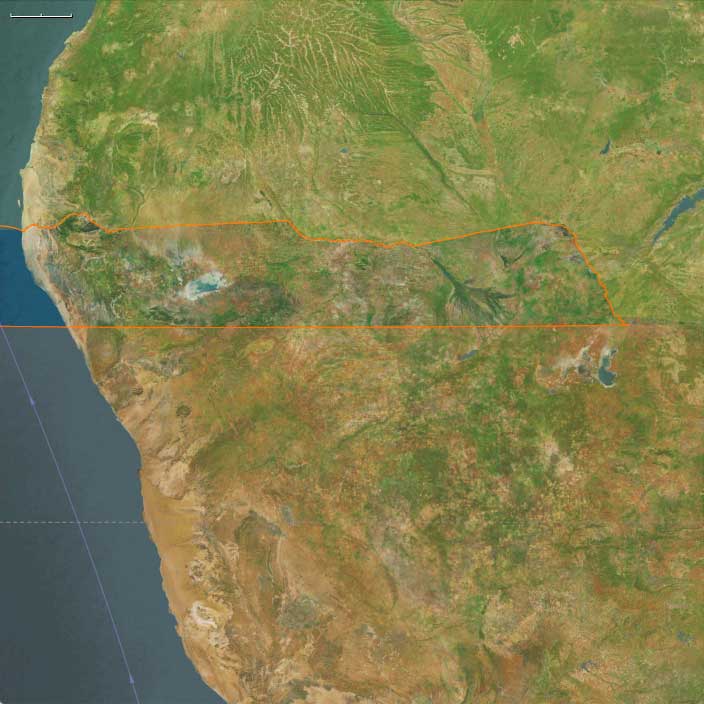

During the Middle Holocene, Southern Africa—spanning the Cape littoral, Highveld grasslands, Drakensberg massif, Kalahari margins, and the great wetlands of the Okavango and Caprivi—entered a period of remarkable climatic stability and cultural flourishing.

The Hypsithermal warm phase brought moderate temperatures, sustained rainfall, and flourishing vegetation across both the temperate south and tropical northern belt, transforming the subcontinent into one of the most biologically and ecologically diverse regions on Earth.

Two complementary cultural worlds matured in balance:

-

Temperate Southern Africa, encompassing the Cape, Highveld, Karoo, and Drakensberg, where fertile coasts and green uplands sustained rich foraging economies and complex spiritual traditions.

-

Tropical West Southern Africa, covering the Okavango–Zambezi floodplains, Etosha Pan, and Skeleton Coast, where mobile floodplain foragers built resilient exchange networks tied to wetlands and seasonal flows.

Together they formed a dynamic landscape of interconnected ecologies and shared symbolic geographies, linking coast, mountain, desert, and delta through trade, migration, and ritual.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal optimum provided one of the most favorable climatic windows in Southern African prehistory.

-

Rainfall was ample and consistent, maintaining perennial rivers and grasslands across the Highveld and Drakensberg foothills.

-

The Cape littoral enjoyed Mediterranean-like stability with predictable winter rains; fynbos vegetation thrived alongside shellfish-rich coasts.

-

Farther north, the Okavango Delta and Zambezi–Chobe–Caprivi floodplains pulsed seasonally with life, though interrupted by occasional multi-year dry spells.

-

Etosha Pan and the Namib coast oscillated between arid episodes and fog-fed fertility, creating contrasting yet complementary resource zones.

This climatic equilibrium enabled population expansion, regional mobility, and the emergence of ceremonial landscapes linking ecological diversity with spiritual continuity.

Subsistence & Settlement

Subsistence in Southern Africa was characterized by ecological precision and adaptive diversity:

-

Temperate regions supported coastal strandloper communities, who harvested shellfish, fish, and seals along the Atlantic and Indian Ocean shores, supplementing with root crops, nuts, and game from inland valleys. Inland, Highveld and Karoo hunters followed herds of antelope and zebra, while upland Drakensberg foragersrotated between grassland and cave shelters.

-

Tropical wetlands of the north sustained complex forager–fishers who harvested water-lilies, catfish, bream, and wildfowl during flood peaks, shifting to nuts, bulbs, and small game as waters receded.

-

Etosha and Caprivi groups established semi-permanent bases on floodplain levees, redistributing fish, meat, and beads through kinship exchange.

-

Across all regions, multi-habitat scheduling—coast, river, highland, and pan—ensured year-round food security and minimized ecological risk.

Settlement was semi-permanent but cyclic, anchored to enduring landmarks such as caves, springs, and rock shelters—places that accumulated generations of ritual memory.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological traditions maintained their microlithic precision and versatility:

-

Stone and bone toolkits were finely adapted for hunting, woodcutting, and fishing.

-

Nets, traps, and fish baskets proliferated in the north; poisoned arrows (notably beetle toxins) became a standard weapon.

-

Along the coast, dugout canoes and rafts facilitated shellfish collection and lagoon fishing.

-

Ostrich eggshell (OES) beads, exchanged over hundreds of kilometers, served as social tokens linking floodplain and inland communities.

-

In the south, the absence of pottery was offset by skillful use of organic containers, leather pouches, and woven baskets.

These technologies, light and portable, reflected societies grounded in mobility, trade, and environmental attunement rather than accumulation.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Southern Africa was crisscrossed by seasonal and ceremonial pathways that linked distant ecologies:

-

The coastal corridors of the Cape connected shellfish gatherers and inland bead-makers, moving marine resources deep into the interior.

-

Highveld–Drakensberg routes carried pigment stones, hides, and ritual objects among cave-sanctuary networks.

-

In the north, the Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando and Okavango–Etosha systems formed arterial trade channels uniting wetland, woodland, and desert groups.

-

Bead trails and kinship alliances bridged linguistic and ecological zones, turning exchange into both material and symbolic diplomacy.

These corridors created a pan-southern web of interaction, through which goods, songs, and stories traversed landscapes as fluidly as the rivers and herds they followed.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

The Middle Holocene saw the intensification of ritual and visual expression:

-

Rock art flourished across the Drakensberg, Cederberg, and Brandberg ranges, depicting humans and animals intertwined in scenes of transformation and trance.

-

In the temperate south, herding motifs appeared long before the actual introduction of livestock—likely symbolic visions of spiritual herds encountered in trance, signifying foresight rather than fact.

-

Rainmaking ceremonies centered in mountain caves and river confluences; paintings often depicted eland, the archetypal rain animal.

-

In the north, engraved boulders and geometric petroglyphs at pan margins and floodplains encoded ancestral narratives of water, fertility, and kinship.

-

Trance rituals and communal feasts synchronized seasonal movement, reinforcing unity among dispersed groups.

Through these symbolic practices, the landscape itself became a sacred archive, every rock face and spring imbued with meaning.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience stemmed from cultural flexibility and ritual reinforcement:

-

Diversified subsistence—combining wetland, coastal, and upland resources—reduced ecological vulnerability.

-

Mobility and alliance networks redistributed food and goods during drought cycles.

-

Ritualized knowledge systems, including rainmaking and divination, acted as adaptive social tools for forecasting and decision-making.

-

The balance of ritual and resource use ensured long-term ecological stability—each harvest, hunt, or gathering framed as reciprocal exchange with the spirit world.

This was an era when ritual and subsistence were one, making spiritual practice itself a strategy of environmental management.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Southern Africa had evolved into a continent of ritual landscapes and ecological mastery.

Foragers across the Cape, Kalahari, and Okavango had not yet adopted herding, but their social, symbolic, and logistical systems were already advanced, sustaining widespread networks and deep cultural cohesion.

The spiritual anticipation of livestock in rock art prefigured the pastoral frontier soon to arrive from the north; meanwhile, the wetland–highland–coast continuum of exchange provided the enduring framework for later interaction between foragers, herders, and farmers.

The Middle Holocene in Southern Africa thus represents a golden equilibrium—a time of abundance managed through ritual, art, and alliance, when people and landscape lived in mutual recognition and rhythm.

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Colorants

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Strategic metals