Southern Africa (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

Southern Africa (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Coasts, Grasslands, and Wetland Arcs at the Ice Age’s Edge

Geographic and Environmental Context

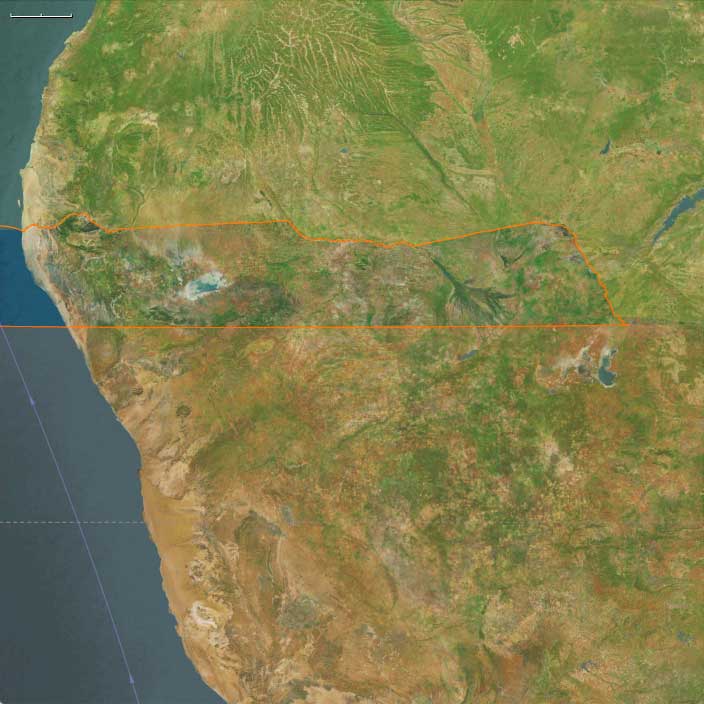

In the late Pleistocene, Southern Africa formed a twin world divided by latitude and rainfall, yet united by mobility and exchange.

To the south stretched Temperate Southern Africa — the Cape littoral, Drakensberg massif, Highveld grasslands, Karoo basins, and Namaqualand semi-deserts.

To the north lay Tropical West Southern Africa, encompassing the Okavango Delta, Etosha Pan, Caprivi wetlands, and the fog-fed Skeleton Coast of Namibia.

-

Along the Cape coast, sea levels stood nearly 100 m lower, exposing vast continental shelves and rich strand-plain hunting grounds.

-

Inland, grasslands extended across the Highveld and Limpopo basins, while the Drakensberg and Lesotho highlands were chilled by frost and occasional glacial patches.

-

Northward, the Okavango–Caprivi–Etosha system acted as an alternating chain of seasonal refugia amid the broader aridity of the Last Glacial Maximum.

-

The Namib fog belt, running down to the Skeleton Coast, linked desert and sea in a unique microclimate corridor.

Southern Africa thus was not a single environment but a pair of ecological theaters — a temperate coast–upland mosaic in the south and a wetland–desert archipelago in the north.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The epoch coincided with intensifying glacial cold across the globe.

Yet within this Ice-Age frame, Southern Africa remained a refuge — drier and cooler than today but never locked in ice.

-

In the temperate south, reduced rainfall contracted woodlands and expanded fynbos, karoo scrub, and open grasslands; winter storms strengthened along the Atlantic margin.

-

In the tropical north, summer monsoon belts retreated, leaving intermittent floods in the Okavango and Etosha basins and stabilizing the persistent fog regime on the coast.

-

Glacial cooling produced strong altitudinal zonation: frost-line vegetation in the Drakensberg, thornveld and savanna below, and semi-desert farther west.

Seasonal contrasts were sharper, but the diversity of habitats offered resilience few Ice-Age regions could match.

Lifeways and Settlement Patterns

Foragers across Southern Africa built dual economies that revolved around mobility between stable refugia and opportunistic resource zones.

-

Temperate foragers (the ancestors of the strandlopers) lived between coast and grassland, harvesting shellfish, fish, and seabirds along the exposed Cape plains, while inland groups hunted zebra, wildebeest, and springbok on the Highveld and Karoo.

Rock shelters in the Cederberg and Drakensberg served as cold-season refuges and social nodes. -

Tropical West Southern foragers organized life around water: fishing, trapping, and gathering in the Okavango floodplains during high water, then shifting to pan edges and spring corridors as the delta receded.

Others ranged along the Skeleton Coast for strandings, shellfish, and eggs, returning inland before the fog belt dried out.

This north–south complementarity gave the region a latitudinal rhythm of survival: coastal–grassland circuits in the south mirrored wetland–pan circuits in the north, both sustained by deep ecological mapping.

Technology and Material Culture

Both worlds drew from the Late Middle Stone Age technological repertoire but tuned it to their environments.

-

Stone industries: flake and blade cores of quartz, chert, or calcrete, with backed pieces and retouched scrapers emerging late.

-

Organic tools: bone points, hide awls, digging sticks weighted by stone rings, and fiber nets.

-

Symbolic and practical innovation: ostrich-eggshell beads for adornment and, more crucially, OES flasks for water storage — a hallmark of Southern African ingenuity.

-

Ochre was ubiquitous in both ritual and hide treatment, anchoring a long symbolic tradition.

While distinct in raw material, these toolkits spoke a common technological language of light, portable adaptability.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Southern Africa’s inhabitants were consummate travelers, moving through a lattice of ecological corridors rather than fixed territories.

-

In the south, the Cape–Karoo–Namaqualand coastline functioned as a continuous forager highway linking shellfish coves and inland grassland basins.

The Drakensberg passes opened seasonal routes between coastal plains and upland hunts. -

In the north, floodplain ridges and island chains of the Okavango guided east–west movement; Omiramba fossil rivers connected wetlands to Etosha; and Zambezi–Chobe–Cuando levees provided trans-basin crossings.

Even the foggy Skeleton Coast formed a linear migration route, its beaches serving as landmarks and occasional larders.

Through such corridors, material styles and ritual customs circulated widely, linking populations across what would later be defined as desert and delta.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

Symbolic life flourished amid this ecological variety.

In the south, ochre-stained burials, bead caches, and early rock art motifs in Cederberg shelters hint at ritual storytelling and ancestral marking of place.

In the north, pigment caches, hearth renewal rituals at pan-edge camps, and the exchange of bead strings performed similar social functions.

Across both zones, color, fire, and pattern embodied continuity: every hearth and painted stone a reaffirmation of belonging in landscapes that never stood still.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Resilience in Southern Africa came from diversification and knowledge rather than abundance.

Foragers mastered micro-climates, timing their movements with rainfall, flood pulses, and marine upwelling cycles.

Technologies such as ostrich-eggshell water storage, tailored hides, and lightweight shelters allowed year-round mobility.

Social networks stretched across biomes, ensuring mutual support during drought or cold snaps.

In contrast to the glaciated north, Southern Africa remained a living subcontinent — its people agents, not refugees, of the Ice Age.

Transition Toward the Last Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, both subregions were firmly established as enduring refugia:

-

Temperate Southern Africa maintained rich coastal and grassland economies, its rock-shelter traditions deepening into the symbolic complexity that would define the Later Stone Age.

-

Tropical West Southern Africa sustained flexible wetland–desert lifeways, its networks of floodplain, pan, and fog-shore camps forming one of the most intricate adaptive mosaics on Earth.

Together they formed a southern hinge of resilience — a world of foragers who thrived, not merely endured, beneath glacial skies.

Southern Africa’s dual systems of coast and delta would endure into the Holocene, exemplifying the Twelve Worlds principle: that human stability arises from ecological plurality, not uniformity.