South Atlantic (6,093–4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — …

Years: 6093BCE - 4366BCE

South Atlantic (6,093–4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Flourishing Ecosystems of Wind and Sea

Geographic & Environmental Context

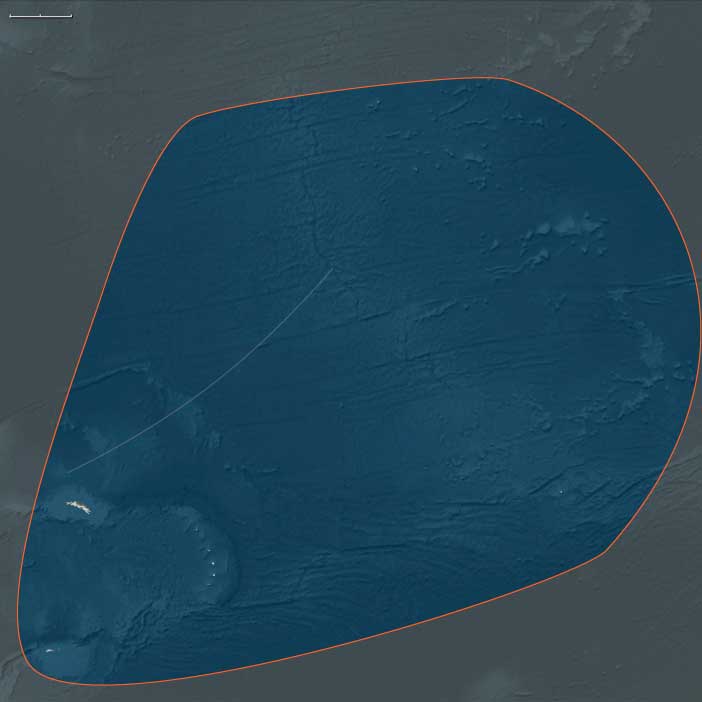

The South Atlantic in the Middle Holocene stretched across a band of subantarctic and mid-ocean islands from the Tristan da Cunha–Gough chain in the north to South Georgia, the South Sandwich, Bouvet, and the South Orkneys in the south, with the isolated Saint Helena and Ascension rising near the equator.

Together, these island arcs and volcanic pinnacles formed an unbroken biological bridge between Africa, South America, and Antarctica, all swept by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) and the Southern Hemisphere westerlies.

Each cluster—northern, mid, and southern—developed distinctive yet interconnected ecological systems: humid cloud-belt uplands, tundra-like grasslands, and glacier-fringed fjords alive with birds and seals.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

By the Middle Holocene, global warming had peaked, producing the Hypsithermal optimum:

-

In the northern and mid-latitude islands (Saint Helena, Ascension, Tristan, and Gough), sea levels stabilized near modern positions, while trades and westerlies reached equilibrium.

-

Cloud forests began to develop on Saint Helena’s summits; Ascension remained arid but sustained fog-fed gullies.

-

In the southern subantarctic belt (South Georgia, South Orkneys), glaciers retreated, exposing fjords and valleys that became colonization zones for plants, penguins, and seals.

-

Bouvet and the South Sandwich Islands, still mostly ice-covered, acted as stepping stones for seabirds, while westerly storm belts maintained constant renewal of nutrients and sediments.

Seasonal sea ice reached its minimum extent of the Holocene, creating a highly productive circumpolar oceanic ecosystem.

Subsistence & Settlement

No humans had yet entered this oceanic realm.

Instead, the region was defined by self-organizing ecological communities that flourished in isolation:

-

Tristan da Cunha and Gough: Volcanic highlands with expanding fern–grass mosaics; tussock meadows supported burrowing seabirds and seals.

-

Saint Helena: Cloud forests of ferns, composites, and tree heaths established on summits, contrasting with xeric lowlands of shrubs and succulents.

-

Ascension: Lava plains remained dry, but fog-capture vegetation stabilized gullies; nesting turtles and seabirds ringed beaches.

-

South Georgia and the South Orkneys: Ice-free valleys filled with moss and cushion plants; tussock grasslands expanded along deglaciated coasts.

-

Penguins, seals, and seabirds formed dense rookeries across the subantarctic arc, their guano fertilizing soils and sustaining invertebrate webs. Offshore, krill and plankton blooms supported whales, fish, and squid in immense abundance.

Technology & Material Culture

Human technology did not reach these islands during this period.

While pottery, ground stone, and domestication spread elsewhere, the South Atlantic remained untouched—a natural laboratory of unmodified ecosystems, where biological succession rather than human engineering drove landscape transformation.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The ACC and atmospheric gyres bound all the islands into a single biological super-system:

-

Whales followed annual feeding circuits from Antarctic krill fields to tropical breeding grounds, using the South Georgia–South Orkney–Bouvet corridor as summer foraging range.

-

Seabirds—especially albatrosses, petrels, and shearwaters—linked Africa, South America, and Antarctica through hemispheric migrations.

-

Penguins and seals shifted rookeries as glaciers receded, occupying new beaches and headlands.

-

In the northern arc, Saint Helena and Ascension lay within the South Equatorial Current, drawing species from three continents and forming a biological connection between tropical and subpolar ecosystems.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

There were no human monuments or myths here, but the islands themselves became ecological calendars:

-

The annual return of penguins, the breeding cycles of seals, and the migration of whales marked the turning of the seasons.

-

Volcanic eruptions, glacier surges, and rookeries’ guano terraces created enduring natural “records” of change—biogenic archives that functioned as the symbolic language of the unpeopled South Atlantic.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Life persisted through flexibility and renewal:

-

Vegetation colonized ash, moraine, and guano-enriched soils; peat formation stabilized moisture and carbon.

-

Bird and seal populations adjusted breeding sites with shoreline evolution; krill and plankton communities tracked sea-ice shifts.

-

Species turnover and recolonization ensured that disturbance—storms, frost, ash, and surge—was a creative force, maintaining diversity and ecological balance.

These systems demonstrated maximum resilience through mobility, reproduction, and opportunistic colonization—adaptations that sustained one of the most productive oceanic ecosystems on Earth.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, the South Atlantic had stabilized into a mature Holocene biosphere:

-

The northern islands (Saint Helena, Ascension, Tristan, Gough) supported rich vegetation belts and nesting fauna.

-

The southern chains (South Georgia, South Orkneys, South Sandwich, Bouvet) thrived as polar–subpolar interfaces, where retreating glaciers met booming life.

-

The ocean between pulsed with krill, fish, and whales, its nutrient loops fueled by the ACC’s perpetual motion.

Still unseen by humans, this was a world already full—a living engine of wind, wave, and migration, poised to endure millennia before the first sails cut across its waters.