South Atlantic (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

South Atlantic (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Gyre Worlds, Glacial Winds, and the Dual Ocean of Life

Geographic and Environmental Context

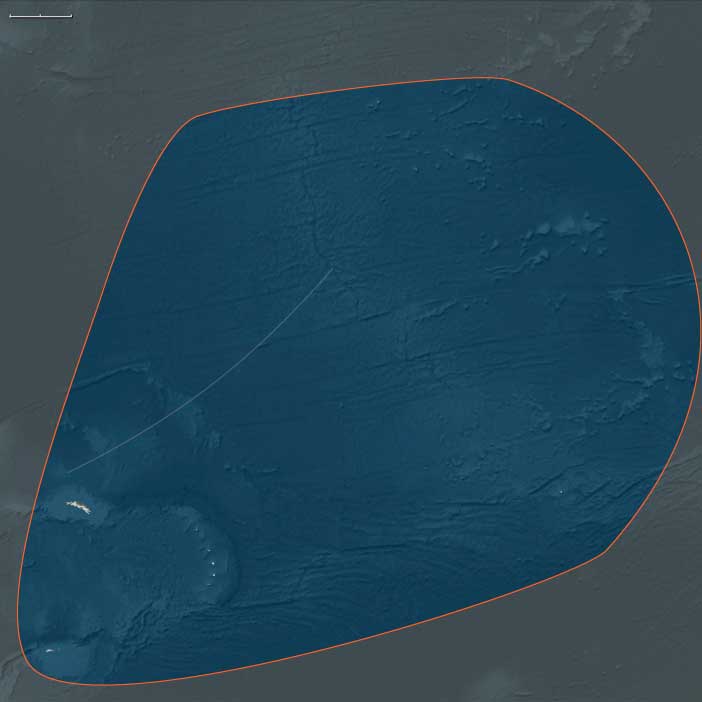

The South Atlantic World in the late Ice Age consisted of two great subregions divided by climate and current:

-

Northern South Atlantic — the warm, subtropical to equatorial half of the basin, centered on the South Atlantic Gyre between Africa and Brazil.

It included St Helena and Ascension Island on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, along with smaller seamounts and reefs scattered between the African and South American coasts.

The Brazilian ridge-islands of Fernando de Noronha, Trindade, and Martim Vaz, though oceanic in origin, belong properly to South America Major rather than this subregion. -

Southern South Atlantic — a cold, subantarctic crescent of Tristan da Cunha, Gough, Bouvet, South Georgia, the South Sandwich Islands, and the South Orkneys, swept by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC).

Together these domains—one bathed in tropical gyres, the other lashed by polar seas—formed a single oceanic system linking Africa, South America, and Antarctica through currents, winds, and migrating life.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

This epoch saw the intensification of the Last Glacial Maximum.

-

Sea Level: 60–90 m lower than today, broadening continental shelves but leaving the steep volcanic islands largely unchanged.

-

Atmosphere: Stronger trade winds spun the northern gyre; circumpolar westerlies sharpened into persistent gales in the south.

-

Temperature: The northern basin cooled modestly but remained tropical; the southern rim dropped far below freezing in winter, with seasonal sea ice pushing northward.

-

Ocean Circulation: The strengthened Benguela upwelling off southwest Africa and the cold-return limb of the ACC enriched planktonic productivity across both subregions.

The South Atlantic thus operated as a thermal bridge—drawing heat northward and nutrients southward.

Ecosystems and Biotic Communities

Northern South Atlantic

-

Islands: St Helena and Ascension were barren volcanic cones with thin soils, patchy grasses, and a few endemic shrubs.

-

Marine Life: Coral reefs persisted in warm pockets; tuna, billfish, and turtles patrolled gyre margins; seabirds nested on cliffs devoid of land predators.

-

Connections: Trade-wind drift and dust from the Sahara fertilized the sea surface, sustaining modest plankton blooms.

Southern South Atlantic

-

Islands: Volcanic or glaciated, from ice-bound Bouvet and South Georgia to the green, cloud-fed uplands of Tristan and Gough.

-

Fauna: Albatrosses, petrels, penguins, and seals crowded beaches and ridges; krill and fish filled the surrounding seas; whales migrated seasonally to feed.

-

Vegetation: Mosses, lichens, and cushion plants clung to ice-free patches; on Tristan and Gough, grasses and peat expanded in sheltered hollows.

Across both subregions, ecosystems were entirely pre-human but highly productive, their nutrient loops linking equator to ice edge.

Technology and Material Culture

Human societies elsewhere in the world—Africa, Europe, and Asia—were mastering blade technologies, tailored clothing, and cave art, yet none had crossed the Atlantic.

The South Atlantic remained wholly unvisited, its distances and storms forming an impassable frontier.

Had mariners somehow reached it, survival would have demanded cold-weather craft, insulated gear, and marine-mammal exploitation far beyond contemporary capacity.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Without people, currents and wildlife defined movement:

-

The South Equatorial Current carried surface waters westward toward Brazil, returning via the Benguela Current up the African coast.

-

The ACC circled eastward around the subantarctic islands, binding the southern oceans into one ecosystem.

-

Migratory species—whales, seals, turtles, and seabirds—traced these routes, forming a living chain that connected polar and tropical worlds.

These same pathways would later shape human navigation and global trade, but in this age, they belonged wholly to the non-human biosphere.

Cultural and Symbolic Dimensions

The South Atlantic existed outside the human imagination.

Its islands, uncharted and unseen, bore only natural symbols—the cyclical return of whales and seabirds, the pulse of storms, and the sculpting of glaciers and lava.

Elsewhere, humans painted caves and buried their dead in ochre; here, the ocean itself was the artist, carving coastlines and layering guano into the first living soils.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

-

Northern gyre ecosystems adapted to cooler conditions with flexible plankton communities and resilient coral refugia.

-

Southern subantarctic systems tracked glacial rhythms: vegetation retreated under ice and recolonized rapidly when temperatures rose; animal colonies shifted breeding sites as sea ice expanded and contracted.

Despite climatic volatility, the basin’s food webs remained stable, proving that biological resilience thrives on movement and interconnection.

Transition Toward the Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, the South Atlantic stood in full glacial balance:

-

The Northern South Atlantic rotated as a warm, slow gyre feeding Africa and Brazil with moisture and marine life.

-

The Southern South Atlantic thundered with westerlies and icy spray, a crucible of upwelling and migration.

No humans yet sailed its waters, yet its two subregions already functioned as distinct worlds—one subtropical, one subantarctic—each more closely tied to distant hemispheric partners than to each other.

When seafarers finally ventured across it tens of millennia later, they would find not an empty sea, but a living engine that had been shaping climates, currents, and ecological continuity since long before human time began.